Management buyouts (‘MBO’s) have become increasingly popular in recent years due in large part to the abundance of available capital in the North American marketplace. They can be particularly attractive as an exit strategy for business owners looking to retire and for corporations seeking to divest of a non-core business segment.

In addition to the many Canadian-based financial investors searching for good MBO candidates, a growing number of players from the United States and other parts of the world are looking to Canada due to the scarcity of good prospects and the quality of the companies and management teams that reside here. Financial investors will compete among themselves for the chance to secure an opportunity that meets their investment criteria.

Financial investors may take a minority equity interest or a majority stake in an investee company, and some financial investors specialize in certain industry sectors. Most financial investors publicize their areas of interest and general investment criteria on their websites.

There a three main parties involved in an MBO: the owner of the company who is seeking to divest, the management team looking to acquire an equity interest, and the financial investor seeking a return on invested capital. In order to be successful over the long term, an MBO must be structured to satisfy the collective, yet sometimes conflicted, interests of these parties. This article examines the financial workings of an MBO, the essential components of the deal and how a facilitator plays a critical role in bringing the parties together.

Financial Workings of an MBO

The financial working of what an MBO commonly sets out to achieve is best illustrated through a (simplified) example. Consider Company A, which generates $5 million in annual earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (‘EBITDA’) and has no debt. The owner of Company A wants to divest and the management team would like to buy an equity interest in the company. Following comprehensive analysis, the parties agree that a price of $25 million for the shares of Company A would be fair, which effectively equates to a multiple of 5x EBITDA. However, the management team collectively can only raise $1 million. Therefore, it seeks one or more financial investors for the remaining $24 million.

Assume that a financial investor is found and that investor assists in raising $10 million of senior and subordinated debt from third party lenders to finance a portion of the transaction, at a blended average interest rate of 10%. The balance of the funds ($14 million) is financed through equity. Therefore, at the outset of the transaction the management team owns 6.7% of Company A (calculated as $1 million invested by the management team divided by $15 million of total equity in the deal), while the financial investor holds the balance. In addition, the management team is granted options that will afford them the opportunity to earn up to a further 10% of the equity in Company A if certain performance targets are met.

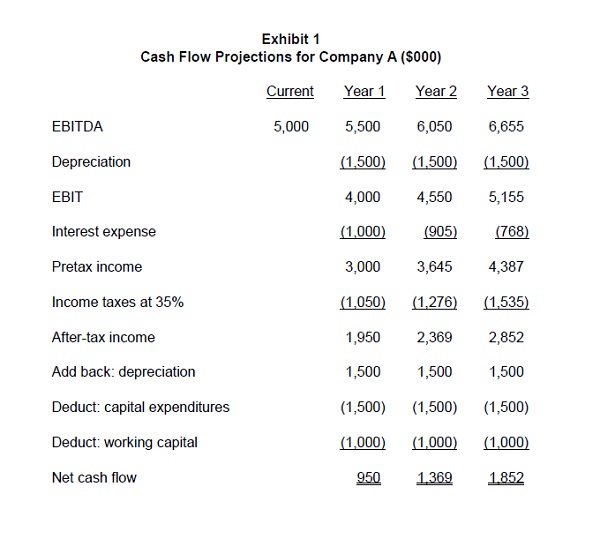

The management team and the financial investor believe that they can grow Company A’s EBITDA by 10% per year in each of the next three years. In order to do so, Company A would have to invest $1 million per year to support incremental working capital and $1,500,000 per year for new capital spending, which approximates annual depreciation expense. Company A pays income tax at a rate of 35%. The management team and the financial investor believe that once growth is achieved, Company A will be an attractive acquisition target for a strategic buyer who likely will pay a price that effectively equates to 6x EBITDA at the end of year 3. Exhibit 1 illustrates the net cash flow that Company A is expected to generate over the next three years:

The cash flows accruing to the equity holders and the rates of return that they expect to achieve are illustrated in Exhibit 2:

As illustrated in Exhibit 2, the equity holders (i.e., the management team and financial investor) initially put up $15 million of equity and finance the balance of the purchase price with debt. The net cash flow generated by Company A each year will be used to make principal repayments on the outstanding debt. Consequently, the amount of debt outstanding at the end of year 3 will decline to $5,829,000. During that time, Company A’s EBITDA is expected to grow to $6,655,000, and the effective multiple that will be paid for Company A is expected to increase to 6x EBITDA due to the company’s larger size and more established market presence. Therefore, the transaction value at the end of year 3 is estimated at $39,930,000. With only $5,829,000 of debt to repay, this leaves $34,101,000 for the equity holders, providing them with a blended return on equity of 31%.

Note that the management team is expected to fare considerably better than the financial investor in terms of their return on equity because of the options that allow the management team’s proportionate interest in Company A to increase to 16.7%. Financial investors purposefully design this type of payoff structure in order to incentive management to perform well, while still allowing the financial investor to realize its threshold rate of return. While threshold rates of return sought by financial investors vary depending on the nature of the investment, a range of 25% to 30% is not uncommon in today’s environment for established businesses having a defendable market position. Higher rates of return generally are sought for riskier ventures.

The Essential Components of an MBO

As illustrated by the previous example, financial investors generally seek companies that offer the following:

- organic growth potential. Financial investors generally are more interested in companies having a sustainable differential advantage in the marketplace and that operate in a growing industry, as opposed to ‘me too’ types of businesses and those in declining industries;

- ability to leverage. By using debt to finance a portion of the purchase price, the return on equity is higher (as is the risk). The debt capacity of a company is a function of the nature and quantum of its underlying tangible assets and its ability to generate cash flows to service debt; and

- exit strategy opportunities. Financial investors generally have a 3 to 7 year time horizon. They seek companies that can either be sold to a strategic buyer or are believed to be good candidates for an initial public offering. These avenues offer ‘exit multiple expansion’, which means that the effective price multiple paid on exit is expected to be richer than that paid on acquisition.

MBO’s are facilitated where the owner has realistic expectations in terms of the price that will be paid for their company. This is not to suggest that financial buyers will not pay a fair price, but that they are less likely to pay a significant premium as contrasted with what might be paid by a strategic buyer. The advantage of dealing with a financial buyer is that they usually will offer a cash deal, whereas other, less attractive, forms of consideration may be offered by a strategic buyer. It also is helpful where the owner is prepared to accept a deal structure that facilitates a transaction. For example, where the owner agrees to retain a partial equity interest in their company, the financing requirements are reduced and financial buyers generally are encouraged by the owner’s belief in the exit strategy prospects. Finally, the owner should expect to offer transitional assistance to the financial investor and management team, where required. For example, an owner who was active in the business should expect to remain active for a period of time following the transaction in order to ensure a smooth transition with employees, customers and suppliers.

Financial investors will thoroughly scrutinize the management team. The assessment of the management team principally revolves around their:

- abilities, including their experience, knowledge, and so on;

- depth, meaning that the Company has a team of competent managers in all key areas of the business (e.g. sales, operations, finance) and that successors can be identified in the event that these individuals leave or must be replaced; and

- commitment, meaning that financial investors will want to ensure that each key member of the management team makes a financial investment into the business, in an amount that is meaningful to them (based on their personal net worth) so that they are deeply committed to making the venture a success.

Importantly, an MBO is not a one-way street. The management team (and the owner who retains a residual interest in the company) should expect to receive more from the financial investor than just a lump sum of cash on closing. Other important considerations include:

- the ability of the financial investor to accommodate follow-on financing that may be needed to support growth or an unexpected shortfall in cash flow;

- alignment of interests with those of management in terms of growth strategies, participation in upside potential and their level of patience or tolerance for shortfalls from plan; and

- value-added service offerings. Financial investors should be expected to provide things such as sound business advice, business contacts, and other services that help the business to grow and prosper.

The MBO Value MatrixTM

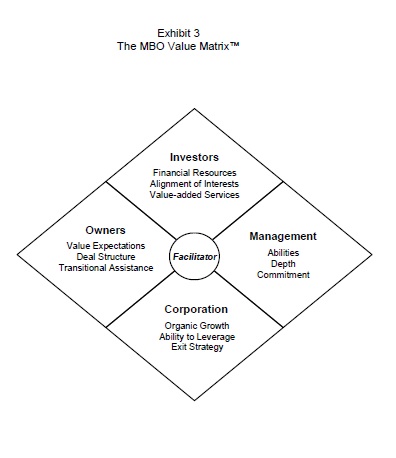

The interests of the various parties involved in an MBO are naturally conflicting to some degree. The owner wants the highest price for their company, management wants the ability to earn a large equity stake and the financial investors are seeking to maximize their own return on invested capital. For an MBO to be successful, all parties must make compromises and structure a deal that creates a 3-way win-win-win. In order to do so, it is critical to engage a facilitator to assist in bringing the parties together. The facilitator normally is a financial advisor (supported by other consultants, such as legal and tax advisors) who not only understands the workings of an MBO, but who also can offer the parties objective advice on the pros and cons of various alternatives. The principal role of the facilitator is to assist both the owner and the management team in identifying and attracting the right financial investor ‘partner’ and in helping to develop the terms of a deal that satisfies the collective interests of all parties. In doing so, the facilitator helps the various parties to identify ways in which they can reconcile their respective positions and preserve a sense of ‘value fairness’ to each. The role of the facilitator within the MBO process is captured in the MBO Value MatrixTM, illustrated in Exhibit 3.

Conclusions

MBO’s can provide a viable exit strategy alternative for owners of established companies, particularly those that offer organic growth potential, the ability to use financial leverage and an attractive exit strategy. The financial payoffs in an MBO can be substantial where forecasted operating results and exit strategy expectations are realized.

MBO transactions are more likely to occur where the owner has realistic expectations as to the value of their company and is prepared to work with the management team and the financial investors in terms of deal structuring and transitional assistance. Key to the MBO is the financial investor’s perception of the management team in terms of their abilities, depth and commitment. The owner and the management team should seek the right financial investor ‘partner’ in terms of their financial resources, alignment of interests and the value-added services that they offer. The MBO Value MatrixTM serves as a framework for illustrating how the facilitator plays a pivotal role in bringing the various parties together and in helping to develop a deal structure that allows all participants the opportunity for value realization.