Many business owners and executives are reluctant to prepare budgets and forecasts for their company on the premise that the future is just too difficult to predict. The one thing that is true about forecasts is that they are always wrong. Despite that reality, where properly done, budgets and forecasts can be a useful tool for shareholder value creation.

Budgets vs. Forecasts

Before proceeding further, we should distinguish between budgets and forecasts. A budget normally refers to the financial projections for a near term time frame, such as the following fiscal year. It represents the targets and objectives for the company, and often serves as a basis for setting management performance objectives. As such, budgets are (or should be) established prior to the commencement of a fiscal year and not modified once approved by senior management or the board of directors.

Forecasts normally refer to a longer-term projection, such as a 5-year period. However, an even lengthier time horizon may be appropriate where the industry in which the company operates tends to experience longer term cycles.

Forecasts normally flow from a company’s long term strategic plan. Forecasts are also prepared in the context of predicting a company’s financial results for its current fiscal year, and are updated based on year-to-date actual results and recent industry and economic developments. The current year forecast is compared to budgeted results to determine whether the company likely will fall short of, achieve, or exceed its targets.

Budgets and forecasts normally are prepared on the basis of annual operating results. However, it is important that monthly and quarterly budgets and forecasts also be prepared (at least for the near term) in order to assess the impact of seasonality within a business and to identify times during the year where additional financing may be required or capacity limitations may be reached.

Decision Making and Shareholder Value

By taking the time and effort necessary to prepare a rigorous budget and forecast, business owners and executives can make more informed decisions. This is because the budgeting and forecasting process forces business owners and executives to ask themselves tough questions, and to be better prepared to deal with different scenarios. For example, if the forecast calls for revenue growth or 10% per year, at what point will the company need to increase capacity, in terms of expanded facilities, additional headcount and other infrastructure requirements? These costs should be factored into the forecast, and management should begin planning for the initiatives that will have to be undertaken to facilitate growth at an early stage.

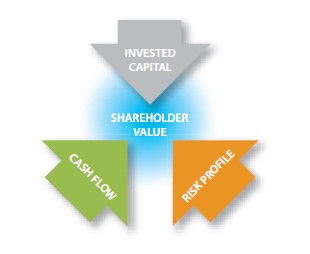

One of the most significant benefits of proper forecasting is that it helps business owners and executives to assess whether the company’s growth initiatives will lead to incremental shareholder value. Business owners and executives often look at measures such as revenues and EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization) to assess how their company is doing. However, growth in revenues and EBITDA does not necessarily translate into greater shareholder value. This is because shareholder value is based on a collective assessment of three inter-related factors, as illustrated in Exhibit 1:

Exhibit 1: The Determinants of Shareholder Value

- cash flow, and specifically discretionary cash flow, which goes beyond EBITDA and takes into account capital expenditure requirements, working capital requirements and income taxes;

- the risk profile of a business, which takes into account the likelihood that forecast cash flows will be achieved; and

- invested capital, which refers to the ability of an organization to use debt in lieu of equity in order to generate cash flows, as well as managing its asset base.

Therefore, a proper forecast will help business owners and executives to assess whether the investments that are made in order to generate future cash flows will ultimately serve to increase shareholder value.

Characteristics of Meaningful Budgets and Forecasts

It takes time and effort to prepare a budget and forecast that will be meaningful for decision-making purposes. In this regard, properly-prepared budgets and forecasts should have the characteristics set out in Exhibit 2:

Exhibit 2

Characteristics of Meaningful Budgets and Forecasts

Detailed Revenues and Expenses

High-level forecasts, which are restricted to gross revenues, total expenses and profit levels, are of little use. While they may reflect the long-term objectives of the organization, significantly more detail is required in order to form the basis for executive decision-making.

For example, revenues should be forecast by customer and by product / service offering. This can be a significant undertaking and difficult to predict. However, it forces business owners and managers to address important issues, such as:

- what proportion of the company’s revenues will come from recurring customers;

- do any customers represent a significant amount of the company’s revenues (e.g. more than 10%); and

- to what extent will new product and service offerings have to be introduced in order to achieve revenue targets?

These factors have a significant impact on a company’s risk profile, which is one of the key determinants of shareholder value.

Similarly, expenses should be sufficiently detailed in order to distinguish between variable costs, fixed costs and step costs, for the purpose of sensitivity analysis (discussed below).

Supportable and Internally Consistent Assumptions

Budgets and forecasts are based on assumptions, which inherently are subjective. However, the assumptions adopted in the budget and forecast should be reasonable and supportable. This means that, where possible and practical, the assumptions should be supported by third party evidence, such as independently published industry growth rates.

As a general rule, the assumptions adopted in budgets and forecasts tend to be more optimistic than not. A meaningful budget or forecast should adopt assumptions that weigh both positive and negative factors.

In any event, regardless of the assumptions that are adopted, it is critical that they be applied in an internally consistent manner. For example, if revenues are projected to grow by 10% in the next year, then the forecast must reflect all of the operating expenses, capital expenditures and working capital required to generate and support that rate of growth. Internal inconsistency is one of the most common deficiencies in financial forecasts.

Sensitivity Analysis

Given that the inputs to a budget or forecast are subjective, it is important that the budgeting or forecasting model allow for sensitivity analysis. Sensitivity analysis is an important tool for decision making. It forces business owners and executives to consider the key “value-drivers” within their business, and the variability of economic returns (e.g. profits and cash flows) to changes in assumptions. As such, sensitivity analysis can be a useful tool for risk assessment and risk mitigation.

As part of the sensitivity analysis exercise, business owners and executives should consider the “degree of operating leverage” within their business. Degree of operating leverage measures the percentage change in earnings before interest expense and income taxes (EBIT) for a given change in revenues. For example, if a 5% decline in revenues results in a 5% decline in EBIT, the degree of operating leverage is 1:1, which suggests a relatively low level of operating risk (at the expense of reduced upside potential). Conversely, if the degree of operating leverage within a company is 5:1, then a 5% change in revenues will result in a 25% change in EBIT. If this level of volatility (i.e. risk) is considered too great, then management may want to adopt a more variable-based expense structure (e.g. paying commissions rather than fixed salaries to sales personnel).

Complete Set of Financial Statements

Too often, budgets and forecasts only contain an income statement. In order to be an effective tool for both decision making and shareholder value measurement, a full set of financial statements is required (i.e. income statement, balance sheet and cash flow statement). Cash flow statements will identify the capital expenditure and working capital requirements in order to generate growth, and whether additional financing will be required to do so. The balance sheet will help in assessing the total capital requirements within the organization, and provide the foundation for metrics such as borrowing capacity, asset utilization and return on capital.

Financial and Non-Financial Performance Indicators

The budgeting and forecasting model should incorporate both financial and non-financial performance indicators. Financial indicators are measures such as profit margins (e.g. net income as a percentage of revenues), financial leverage (e.g. total debt to equity) and asset utilization (e.g. revenues divided by total assets). The various financial indicators should ultimately culminate in a return on equity, which is an important measure of shareholder value.

The problem with financial indicators is that they tend to measure end results and symptoms of underlying issues. Therefore, it is important to consider non-financial indicators as well. Non-financial indicators include such measures as revenues per employee, capacity utilization and gross profit per unit. Trends in non-financial measures tend to be leading indicators of potential issues and opportunities. In particular, non-financial indicators can help management in assessing possible capacity constraints (in terms of employee availability, production capabilities and so on), which in turn can help in the company’s strategic planning process.

Other Benefits of an Established Budgeting and Forecasting Process

A credible and internally consistent forecast forms the basis for measuring shareholder value pursuant to the discounted cash flow valuation methodology, which in both theory and practice is the preferred basis for value determination. This can help business owners and executives to measure whether shareholder value is being created over time.

Another benefit of the budgeting and forecasting process is that it helps to communicate the concept of shareholder value among employees and middle-level managers, which may influence their decision making. Having management participate in the budgeting and forecasting process can also help in securing employee buy-in to the longer term goals of the organization.

Finally, business owners and executives who are considering a corporate divestiture at some point in the future will benefit from a well established budgeting and forecasting process. Creating a credible forecast will help in demonstrating value to a prospective buyer and in negotiating a better price and deal terms.

Initially, a considerable amount of time may be needed to prepare the financial model and consider all of the variables. However, the budgeting and forecasting process generally becomes easier over time, as business owners and executives begin to develop a mindset for the variables that need to be considered, and relatively minor modifications to the financial model are required.

Summary

Budgets and forecasts do not create value in and of themselves. Rather, properly prepared, a budget and forecast can be a powerful tool to help business owners and executives in their decision-making process, and to ensure that growth initiatives are likely to result in greater shareholder value.

In order to be meaningful, budgets and forecasts should be sufficiently detailed, backed by supportable and internally consistent assumptions, and with sensitivity analysis capabilities. Budgets and forecasts should also contain a complete set of financial statements as well as both financial and non-financial metrics. While the time and effort required to prepare meaningful budgets and forecasts should not be underestimated, the payoff can be well worth the investment.