Throughout the CEE/SEE region, the percentage of non-performing loans (NPLs) to total loan receivables has increased dramatically during the current economic cycle.

In many areas, lenders appear to have reacted to this by pursuing a strategy occasionally called "extend and pretend." But in light of ever increasing regulatory (capital) pressures concerning flawed banking assets, we believe that many regulated lenders may be left with little choice other than more actively managing distressed borrowers/portfolios.

On the other hand, there is increased buy-side demand for distressed credits in a variety of industries and across asset classes, which in turn should allow current creditors to consider disposals of credit exposures (single names and portfolios) as part of the strategic management of distressed exposures.

We therefore take great pleasure in presenting to you our thoughts on some key legal issues that should be considered carefully by sell-and buy-side industry participants when looking into the viability of NPL transactions (single names and portfolios) in the region.

If you wish to discuss any of these issues in greater detail, please feel free to contact the authors of this guide, any of the members of Schoenherr's distressed assets team or any of your usual contacts in our firm.

A BRIEF LOOK AT THE FACTORS DRIVING NPL TRANSACTIONS IN THE REGION

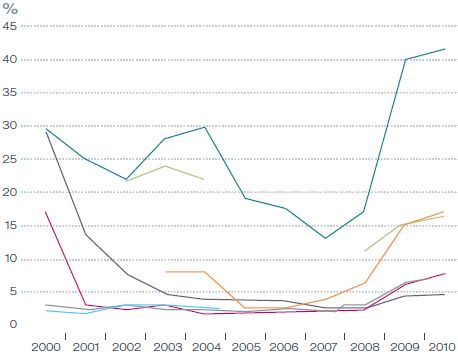

In the last decade, in particular the current economic cycle, there has been a dramatic increase in the percentage of non-performing loans to total gross bank loans throughout the CEE/SEE region (see chart below; the data is based on the International Monetary Fund, Global Financial Stability Report).

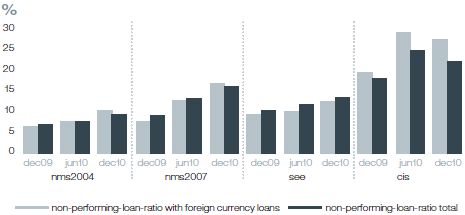

The June 2011 financial market stability report (Finanzmarktstabilitatsbericht) by the Austrian National Bank (Oesterreichische Nationalbank (OeNB)) notes that there has been constant growth of NPLs in percentage to total gross loans across all CEE countries in the period between the last quarter of 2009 and the last quarter of 2010 (Source: OeNB, Finanzmarktstabilitatsbericht 21, June 2011). The following graph, taken from the OeNB's report, illustrates that for foreign currency denominated loans the situation is even more drastic.

This rapid increase of NPLs combined with ever increasing banking regulation throughout Europe and the impact of those assets on institutions' risk-weighted assets (RWAs) encourages credit institutions in the CEE/ SEE region to reconsider their long-term strategies concerning non-core and distressed assets.

Under the new Basel III regulations, which will be implemented in the EU by 2013 (subject to transitional provisions), credit institutions have to gradually increase their capital base. In addition, as part of the EU-level agreement on measures to restore confidence in the banking sector, certain European credit institutions are required to establish a buffer, so that the Core Tier 1 capital ratio reaches 9% by the end of June 2012.

Moreover, according to recent regulatory initiatives in Austria, certain banking groups will be required to apply Basel III capital standards as of 1 January 2013 (no phase in). These initiatives also introduce a maximum loan to deposit ratio of 110% for the CEE/SEE subsidiaries of these banks.

As a consequence, institutions are looking for options to reduce their balance sheets, thereby improving capital ratios, which should lead to further disposals of distressed assets.

Furthermore, on 27 October 2011 the ECJ handed down a judgement that clarified the VAT treatment of certain aspects of NPL transactions. By increasing transaction confidence for market participants, this judgement should also help close the current pricing gap between sell-side and buy-side.

SOME CONSIDERATIONS ON NPL TRANSACTIONS

As in any other transaction, legal and regulatory issues are only some of the aspects that impact the success or failure of structuring, implementing and executing a buy- or sell-side NPL transaction. Other key driving factors include the economics of the deal, accounting, tax, reputational and general risk management considerations. But in our experience, legal considerations (including in relation to servicing and enforcement) are among the key drivers when it comes to selling or buying a portfolio of distressed credits. This is not only due to the nature of the parties involved (in particular regulated sell-side businesses), but mainly due to the nature of the assets involved in the transaction, whether a single-name loan or a portfolio of consumer credits.

Below we have set out our thoughts on how to strategically approach a sell- or buy-side NPL transaction. Whereas this guide focuses on portfolios of non-performing corporate and consumer loans, many of the issues addressed will also be relevant to single name transactions in large corporate exposures.

This guide is structured according to transaction stages, from pre-transaction decision-making, via structuring aspects and transaction execution to post-execution servicing.

Pre-transaction aspects (decision-making)

A potential sell-side credit institution has many options for managing its clients in distress, ranging from restructuring the debt (which in the region is often confined to extending tenors and granting covenant holidays) to forcing borrowers into liquidation.

When considering whether disposal of certain assets or asset-classes may be an optimal strategy for actively managing distressed credits, the management of the potential sell-side institution will have to carefully consider whether the perceived negative effects are outweighed by the advantages.

On the down side, there may be negative effects on an institution's financials, because of losses realised on sale of assets that are not marked-to-market in an institution's books, in combination with the threat of foregoing the upside that may potentially come from a successful recovery or even from enforcement. In addition, many institutions may be concerned about managing reputational aspects. For example, they may fear media reports about selling claims against widows and orphans to aggressive investors.

On the other hand, the most obvious benefit of a successfully completed sale of NPLs is the effect on risk-weighted assets (RWAs) and the resultant freeing up of equity. Selling institutions have also received positive market and shareholder feedback (including rising stock prices once a transaction or series of transactions has been announced and completed) as well as positive ratings response to the improvement/enhancement of on-balance sheet assets that continue to be held by the institution and to the more focussed approach to core activities, such as originating new business while "outsourcing" certain aspects of problem loan management.

» Challenge yourself (sell-side)

- Do I have the organisational and managerial capacities to manage and service distressed exposures in a value-preserving manner and at least in the same quality as experienced third-party special servicers?

- What will be the likely effect on my financials of selling non-performing loans (substantially) below par?

- Will my investor relations/public relations unit be able to manage reputational aspects?

- Am I able to define a portfolio that suits expectations on credit quality, maturity and pricing?

Structuring aspects

Once an institution concludes that disposals of single names or portfolios of non-performing loans form an important pillar of its overall strategy of actively managing its problematic exposures, it is time to decide on the overall transaction structure (auction process, negotiated sales, etc.) and to start the nitty-gritty vendor due diligence process that precedes most successful sale transactions.

Accurate, reliable and complete data about the non-performing loans are the key to maximising sales proceeds. It is often at this stage of preparing information for potential investors when institutions learn more than they ever wanted to know about their own customers/borrowers and in particular the quality and consistency of documentation and data available in relation to the distressed credits. In addition to practical aspects in relation to the completeness of documentation and data quality, one has to consider that any sell-side (credit) institution will normally be bound by data protection and banking secrecy laws that limit or even prevent the full disclosure of data to potential buy-side institutions and their advisors.

However, that dilemma can usually be overcome in a manner that satisfies compliance considerations as well as investor due diligence requests. The available options range from disclosure of anonymised and aggregated data only, to full disclosure of the credit documentation to due diligence advisors formally appointed/endorsed by the selling institution, who in turn produce a report to the potential investor on an aggregated and no-names basis only (i.e., without referencing specific loans and customers).

Since a fully-fledged buy-side due diligence of each and every credit file will often not only run afoul of limitations on information disclosure and data transfer, but also will be very costly, management of the selling institution should consider what it takes for the selling institution to become comfortable that a sample of, say, 5% to 10% of all loan contracts relative to transactions included in the portfolio constitutes a representative sample of documentation used. Once this level of comfort is achieved (i.e., once the sell-side institution has established that there are no significant deviations in documentation standard), buy-side due diligence could be limited to the loan contracts included in this sample and representations to this effect in the sale/purchase documentation could be offered to investors.

During this pre-sale vendor due diligence process, any sell-side institution will also be well advised to scrutinise the credit files relating to the portfolio to be sold to determine whether they contain only the information and data required by a potential buyer for enforcement purposes (since data disclosure would often be limited to data on a strictly need-to-know basis; see below).

To achieve a bankruptcy remote transfer of the NPLs (a true sale), structuring considerations will come into play during this phase of a transaction. In addition to tax (particularly VAT and withholding tax considerations), the structure will largely be driven by the legal aspects of the transferability of loans and related security interests and the resulting structure proposal (trust, true sale, spin-off or de-merger – see below) will have to be reflected in the transaction documentation proposed to potential investors by the seller.

» Challenge yourself (sell-side)

- Have I used consistent documentation when originating the loans subject to the transaction?

- Are all required customer consents to data processing and information disclosure available? How else can I transfer/disclose data and information during due diligence stages and afterwards?

- Am I in a position to strip-off non-core information from the credit files so that disclosure can be limited to data and information on a needto- know basis?

- Are the loan receivables and related security interests transferable (under the terms of the contracts and governing law) or do I need to explore a corporate transaction, such as a spin-off/de-merger of the portfolio?

Buy-side institutions, on the other hand, when gearing up to participate in a sales/auction process, will be keen to validate their pricing and valuation models against the local legal environment (e.g., their assumptions in terms of collection and enforcement proceedings). Moreover, they will be looking into setting up a legally compliant and tax efficient acquisition structure, where their focus will be on compliance with local banking and servicing regulation. Not least, they will be looking into how the acquisition will be financed.

» Challenge yourself (buy-side)

- Do I have the requisite local experience to adequately price the NPL portfolio or is additional due diligence on the local legal and tax regimes required?

- Will the structure I usually use be feasible in the local environment? In particular, will the acquisition vehicle or the servicing vehicle (if different) have to be licensed?

- Is professional servicing expertise available locally or do I have to build this and at what cost?

Transaction execution

Sell-side institutions will usually be looking at a two-stage sales process, which would commence by asking interested bidders for indicative bids based on a standard information package or fact book made available by the seller.

After this pre-selection process, short-listed bidders would normally be granted access to additional information so as to allow them to complete their due diligence and to submit binding bids. The contents and level of detail of the data room/data tape and relating access rights will be driven by competition considerations as well as banking secrecy and data protection laws (see above).

In a well-structured process, at this stage the proposed transfer and servicing documentation would be made available by the sell-side institution to shortlisted bidders. Documentation will largely be driven by issues relating to the transferability of loan receivables and related security, where parties aim at achieving a transfer without debtor involvement while avoiding excessive costs, such as the costs of security re-registrations. Transferability aspects, for example, will be decisive in establishing whether a true sale of the assets can be implemented or whether the portfolio will have to be hived-off from the selling institution's balance sheet into an SPV by means of a corporate transaction with a subsequent sale of that SPV's shares to the investor.

Irrespective of whether the parties pursue an asset or share deal transaction, any buyer will be well advised to not only focus on the desired receivables and security interests transfer, but to also verify whether the structure chosen may have undesirable effects in terms of liability and/or employee transfers (such as being treated under local laws as a transfer of a business unit) and, if so, how these risks can best be mitigated.

In addition to the receivables transfer documentation, agreements governing the servicing and enforcement of the receivables sold and purchased will normally have to be put in place. Whether the servicing will be performed by third-party servicers or by the selling institution on behalf and for the account of the purchaser will, in addition to banking secrecy and data protection considerations, be determined on the one hand by the servicing capabilities of local special servicers and the selling institution, and on the other hand by reputational considerations of the selling institution in relation to servicing on behalf of, and at the instruction of, the investor.

Other ancillary documents may include a data trust agreement if the involvement of a data trustee is required from a banking secrecy and data protection perspective, even in regards to non-performing loans, and financing documentation at the buyer's end.

» Challenge yourself (buy-side)

- Does the transfer documentation result in a bankruptcy remote transfer of the loan receivables, related security and other ancillary rights to the purchaser?

- Will the proposed transfer mechanism require the involvement of debtors or trigger costly and/or cumbersome notifications or re-registrations?

- Is there a risk that the transfer will also trigger the assumption of liabilities and/or employees attached to the loan portfolio by the buyer? How can this be avoided/mitigated?

- Does the transfer documentation provide for a timely transfer of sufficient data to the servicer to allow a seamless continuance of servicing/ enforcement?

Post-execution servicing

Once the data needed by the servicer to perform its duties are available to it and once credit files have been handed over, the transaction will enter into the key-value driving stage. The buyer's return will depend primarily on the results yielded by the servicer when servicing the portfolio and when enforcing the loan receivables and related security as well as on the time needed to recover the non-performing loan receivables.

At this stage debtors will attempt to raise various types of defences, both in relation to the underlying credit and security documentation as well as in relation to the validity of the transfer to the buyer. The buyer will therefore have to concern itself to provide local law compliant evidence of transfer to local courts and enforcement authorities.

» Challenge yourself (buy-side)

- Does the servicer hold all licences required under local laws to perform its duties?

- Has the buyer/servicer obtained all documentation required to service the loan portfolio (credit files)?

- Has the buyer obtained all means of evidence required under local laws to prove the validity of the transfer of receivables, related security and other ancillary rights to local courts?

GUIDE BY JURISDICTION

The solutions that we think may be available for some of the key structuring considerations identified in the general sections of this guide are set out below for each jurisdiction.

The limitations resulting from secrecy obligations (data protection and banking secrecy, the latter of which is enshrined in Austrian constitutional law) at due diligence stages are usually addressed by appropriate precautions to avoid customer-specific disclosure to investors. The general view, which is also confirmed by the Supreme Court with respect to a subrogation structure, is that secrecy obligations should not bar a credit institution from selling and assigning loans, since in particular in respect of non-performing loans, the interests of the bank outweigh the customers' legitimate interests to keep their data secret. Even once the transaction has been executed, however, data and information disclosure should only occur on a need-to-know basis. Only the information required to service and enforce the receivables should be disclosed.

Despite factoring being a regulated banking business in Austria, the purchaser's potential licensing requirements are usually overcome by structuring the transaction in a manner that the purchaser qualifies as securitisation SPV. This may also be beneficial from a banking secrecy perspective. Alternatively, the buyer could use a foreign acquisition company, thus arguing that no regulated business is performed in Austria.

When using a foreign acquisition company for non-performing mortgage loans, tax considerations will be decisive in determining the acquisition company's jurisdiction (treaty relief for limited lender taxation applicable to interest income secured on Austrian real estate).

The assignment of receivables and related security can normally be accomplished in a manner that qualifies as a true sale. With respect to the maximum amount mortgages frequently used by Austrian credit institutions, however, certain pre-transfer steps will have to be implemented in order to convert the mortgage and to allow for a legal assignment by way of subrogation (Einlosung). Subrogation generally leads to a transfer of all rights by operation of law and may generally be a preferred structure with respect to many types of secured loans. If conversion and subrogation is not an option, it may be worth exploring a transfer of the portfolio to a newly set up SPV by means of a de-merger (Spaltung), which would require the consent of the banking regulator and bring about new regulatory challenges. For receivables where an enforceable court judgement already has been obtained, additional form requirements apply to the transfer.

Enforcement of secured claims involves Austrian courts and enforcement officers, unless the transaction relates to corporate loans, where the originating bank and borrower often will have agreed on out-of-court enforcement. Contrary to some other jurisdictions, however, the SPV holder of the loan receivables would be treated akin to an Austrian credit institution, since they do not enjoy special privileges on enforcement, with few exceptions available if security in the form of financial collateral was granted.

Under Bulgarian law assignors are under a statutory obligation to provide assignees with all documents concerning assigned receivables. Since these might include documents containing personal data or facts and circumstances subject to banking secrecy, the interaction between this statutory disclosure requirement on the one hand and data protection and banking secrecy limitations on the other merits particular attention. As far as data protection is concerned, we believe that the originating and selling bank's legitimate interest to raise financing by assigning loan receivables should prevail over the interests of the debtor, especially with respect to non-performing loan receivables. While not yet tested before Bulgarian courts, we believe that a reasonable solution with respect to non-performing loans from a banking secrecy perspective is to uphold the bank's interest to assign receivables under such loans, thereby enabling it to clean its balance sheet and to generate some liquidity instead of attempting to collect its claims in lengthy and cumber-some enforcement proceedings. Bank secrecy should therefore not be an obstacle to disclose information about the debtor, but disclosure should be made only on an as needed basis. This approach already has been adopted by courts in some EU jurisdictions (notably Germany and Austria), which is an additional argument for Bulgarian courts to follow suit. We believe that the "legitimate interest" exception from personal data protection rules could be applied mutatis mutandis to bank secrecy restrictions.

From a financial services regulatory perspective, the general rule is that the acquisition of receivables arising from credit agreements may be performed locally as a "main activity" (bringing 50% or more of the net revenues or corresponding to 50% or more of the balance sheet total) only by credit institutions (local or EU/EEA under EU passporting rules) or by financial institutions registered with the Bulgarian National Bank. While this registration does not imply fully fledged supervision (compared to a credit institution), the acquirer will only be able to operate under an unregulated regime if the acquisition of receivables is performed outside Bulgaria. There is no express statutory rule or practice in Bulgaria shedding light on the issue of when a particular banking activity (including acquisition of receivables) is to be regarded as being performed in Bulgaria or outside of Bulgaria. The implementation of a transaction that avoids being caught by the local regulatory regime will therefore require careful structuring. Once regulatory constraints on the purchaser are avoided, however, the transaction may be implemented in an unregulated environment, since the activities of collection agencies are not subject to licensing/registration requirements in Bulgaria.

Loans receivables (whether performing or not) and related security interests can be transferred either by assignment or, likely, by contractual subrogation. Depending on the asset/portfolio in question, the parties may opt to implement either structure. This is because assignments need to be registered to be effective with respect to certain types of security interests (notably real estate mortgages and non-possessory pledges). Depending on the size of the portfolio, such registration may be a time-consuming and costly venture. Contractual subrogation, a structure which is not tested before Bulgarian courts, but is supported by the predominant doctrinal opinions in Bulgaria, would on the other hand achieve a transfer of the loan receivables and all ancillary rights (including related security) without any registration, thus bringing cost-effectiveness.

If none of these structures are feasible, the demerger of part of the originating bank in order to transfer the non-performing portion of the loan receivables might also be an option, provided that permission in writing issued by the Bulgarian National Bank can be obtained.

NPL transactions in the Czech Republic date back to the late 1990s. At that time, Česka konsolidačni agentura purchased NPLs from state-owned banks so that they could be privatised at a reasonable price. Czech banks have since adopted a more conservative approach to lending. Accordingly, and thanks to the stability of the Czech economy, NPLs in the Czech Republic are currently lower than in most other CEE jurisdictions (6.4% in March 2011).

NPL transactions usually take the form of an assignment of receivables (an asset deal), because no debtor consent is required, unless the parties specifically agree otherwise. As blanket assignments are not specifically recognised by Czech law, the assignment agreement needs to identify the transferred receivables in a sufficiently specific manner. For example, the assignment can relate to a certain group of receivables, such as receivables arising under a framework agreement, or can specify receivables by reference to the debtor and contract number as long as it is unique. According to the recent practice of the Czech Supreme Court, requirements for specification tend to become less formal. For example, a mistake in the amount of receivables transferred does not invalidate the assignment agreement.

In addition to a relaxed regulatory regime, NPL transactions in the Czech Republic are facilitated for purchasers because security instruments, including mortgages, pledges and other accessory rights such as default and contractual interests, transfer by operation of law. Security interests can therefore be enforced by the assignee based on an assignment agreement governed by foreign law that needs to be translated into Czech when seeking enforcement before Czech courts. Re-registration of security interests in the purchaser's name is not required, which saves not only time, but also notarisation and translation costs.

On the other hand, parties need to specifically agree for contractual penalties or damage claims to transfer, as they are not deemed accessory rights.

Another clear advantage is that the acquisition of NPL portfolios is not regarded as a banking activity. A purchaser of an NPL portfolio does not therefore require a banking licence. If a Czech subsidiary or a Czech branch of the purchaser acquires the portfolio, it will need a local trade licence to administer and collect receivables, including factoring, which is relatively easy to obtain. No trade licence is needed if a foreign investor makes a cross-border purchase of the NPL portfolio and then services it via a local collection agency.

Before 2000, bank secrecy was not an issue, as full documentation was disclosed during due diligence in the sale process to Česka konsolidačni agentura. While this approach has since changed, recent Supreme Court decisions support the view that bank secrecy obligations do not prevent a credit institution from assigning its receivables. Similarly, data protection legislation limiting disclosure of data has to be considered, in particular if consumer credit portfolios are concerned. As the Czech Data Protection Office is known for its strict enforcement practice, we recommend anonymising customer information for any due diligence purposes.

Unlike in other jurisdictions, regulated entities do not enjoy special enforcement privileges. If the assignee wants to collect receivables in relation to which insolvency or enforcement proceedings are pending, a certified translation of the assignment agreement with notarised and appostilled or super-legalised signatures must be presented to the court.

The Hungarian NPL market is not yet well developed, but is expected to grow in the near future. The most important market players are factoring companies belonging or closely connected to banking groups and principally charged with deleveraging banks' balance sheets to comply with increasingly stringent capital adequacy rules. Thanks to relatively easy transaction execution, unsecured consumer loans are the most commonly sold loans, generally at huge discounts.

According to our information, international NPL funds or similar institutions are not yet very active on the Hungarian market. This may be attributed in part to local licensing as well as banking secrecy and data protection rules, which are the major hurdles to be overcome in transaction structuring. With factoring being a regulated banking business, arguments that a foreign SPV would not be performing licensed activities in Hungary will likely not be accepted by Hungarian authorities, because the receivables purchased relate to loans of Hungarian borrowers. The most practical way of structuring a transaction would therefore be a scenario in which the purchaser qualifies as a securitisation SPV. In that case an exemption from licensing requirements may be available, although regulation appears somewhat ambiguous. While the exemption has not yet been tested and there is no solid market practice on securitisations generally (as the respective law dates from 2010 only), we believe that the law may be construed in a way to support the securitisation SPV exemption. Nevertheless, preliminary discussions with the Hungarian regulator prior to implementing securitisation SPV structures should be considered.

Aside from licensing and regulation, banking secrecy and data protection rules are a further challenge for NPL transactions. As a principle, banking secrecy and data protection rules should not prevent a credit institution from selling or enforcing its loans if this is in the best interest of the credit institution. Although this can certainly be argued in an NPL context, the "overriding interest" argument is only available to credit institutions, but not to securitisation SPVs. This creates a significant burden, as the securitisation SPV could be prevented from outsourcing debt collection to a local collection agency, because transferring data to, and processing data by, such a collection agency would be critical from a banking secrecy and data protection perspective. From a deal structuring perspective, this likely means that a securitisation SPV must either rely on the selling bank as the future servicer of the receivables or must service the portfolio itself (unless the collection agency was still appointed by the selling credit institution). Also, the "overriding interest" qualification arguably limits data and information disclosures in the course of NPL transactions (including during due diligence) to strict "need-to-know" disclosures.

Assignments of receivables and related security can usually be accomplished in a manner that qualifies as a true sale without having to undergo cumbersome and/or costly security re-registrations. With the exception of maximum amount mortgages (keretbiztositeki jelzalog) collateral, as a rule, transfers together with the assigned receivable. Re-registration of security interests in the purchaser's name is therefore not required to validly transfer the security interest to the purchaser. This is different with maximum amount mortgages, which are frequently used by Hungarian credit institutions to secure revolving facilities, for example. Here, transfer of the maximum amount mortgage with the underlying (secured) obligation (the NPL) is far from straightforward. Long-standing Hungarian court practice is of the firm view that a maximum amount mortgage secures and is therefore connected to the entire legal relationship (the entire banking relationship), but not to individual claims (the NPL). Since maximum amount mortgages can only transfer with the entire legal relationship secured by the mortgage, but not with an individual claim, one precedent concluded that upon termination of the entire relationship and acceleration of the loan, the maximum amount mortgage is converted into a fixed amount mortgage and automatically transfers as an accessory right to the loan receivables to the purchaser. But this practice is not universally accepted and there are also contradictory rulings.

Enforcement of secured claims involves Hungarian courts and enforcement officers, unless the parties have agreed on out-of-court enforcement. However, only credit institutions are entitled to certain out-of-court sales privileges if contractually agreed with the debtor. These privileges would not pass to an unregulated purchaser.

NPL transactions are facilitated in Poland by enabling banks to freely trade in receivables without the debtor's consent and relieving them from banking secrecy obligations, along with a favourable regulatory regime that does not subject purchasers to financial services licence requirements.

In terms of structuring, sales to securitisation funds (a special type of closed end investment fund) are the most popular and advantageous structure for NPL portfolio transactions on the Polish market. Fund managers usually entrust servicing of receivables purchased, including debt collection, to special servicing companies which require a local authorisation of the Polish Financial Supervision Authority. Polish law further allows trades in receivables without the debtor's consent in case of so-called "lost receivables", which are mainly receivables overdue for more than 12 months or receivables where the bank has initiated enforcement proceedings) as well as in a procedure referred to as "public sale of bank receivables". Currently, these two possibilities have less practical significance because of the tax benefits available when selling portfolios to securitisation funds.

Banking secrecy regulations follow the above transaction mechanisms. Banks are relieved from confidentiality to the extent necessary for concluding and performing transfers of receivables to a securitisation fund. Similar exemptions are available for the other two alternatives referred to above (sale of "lost" receivables and public sale of bank receivables).

The exemption also extends to servicing of receivables by a special servicing company. While the secrecy exemption does not yet apply at due diligence stages, this could be structured in a way that the bank mandates/ endorses advisors, who would then be bound by banking secrecy and would produce due diligence reports containing aggregated and hence not sensitive information only.

Transfer of receivables secured by a mortgage results in a transfer of the mortgage; however, the transfer of such receivables requires registration of the purchaser in the respective land and mortgage register. The necessity to register the change does not affect the priority of the security interest. The transfer of a registered pledge only takes effect upon the entry of the purchaser in the register of pledges. Rights under sureties are generally considered accessory and will transfer by operation of law together with the receivable.

Clearly the main difficulty for true sale transactions is the time-consuming and costly transfer of receivables secured by mortgages or registered pledges. As an alternative, banks may enter into sub-participation agreements with securitisation funds under which a bank undertakes to transfer all proceeds realised from the sold receivables to the securitisation fund. Sub-participation does not therefore involve a transfer of receivables as such, but a transfer of proceeds only, and would accordingly not require re-registration of security interests. Claims against the bank under a sub-participation should be bankruptcy remote, meaning that the bank's receiver will continue paying out proceeds to the fund.

Secured claims are usually enforced in court, unless the loan is secured by collateral, which may be enforced out of court by taking ownership, private sale, etc. Polish banks enjoy special enforcement privileges, which do not pass to the SPV or the fund purchasing such receivables. Purchasers of receivables would therefore need to resort to time-consuming regular court enforcement procedures, a further reason for considering a sub-participation rather than a true sale deal structure.

The Romanian market has witnessed some transactions (or at least attempted transactions) during the current economic cycle. While the legislator has facilitated the regulatory regime concerning certain categories of NPLs, other aspects, in particular concerning disclosure and true sale considerations, warrant particular attention.

From a regulatory perspective, the acquisition of loan receivables is viewed as a form of crediting activity, as is factoring, and therefore in principle is reserved to regulated entities, either licensed locally or passported. Licensing requirements are more relaxed, however, with respect to loans that qualify as "loss" and related receivables, which may be assigned to unregulated entities, and assignments to securitisation vehicles, which are only subject to limited supervision by the Romanian Securities Commission. Loans qualify as a "loss" if the borrower has outstanding payments overdue for more than 91 days and/or if the borrower undergoes bankruptcy and/or if enforcement has commenced against the borrower. In light of these limitations, potential structuring options involving a cross-border assignment may have to be further discussed with the regulator. In any event, an acquirer of loan receivables may service and collect the acquired receivables itself or via an appointed agent, as servicing and collection do not carry licensing requirements in Romania.

Although assignments to non-regulated entities are permissible in certain circumstances, Romanian law does not contain an express exemption from banking secrecy and data protection in relation to assignments to such privileged entities. In respect of professional (banking) secrecy limitations incumbent on credit institutions and financial institutions, specific information in relation to loan receivables and debtors may be disclosed in certain limited scenarios only, including for "legitimate interest" of the disclosing party. In the absence of any specific guidance or interpretation by Romanian authorities on what constitutes a "legitimate interest", we

take the view that disclosure of specific information subject to secrecy rules should be avoided during due diligence stages. Furthermore, such disclosure should be made to an assignee/transferee under NPLs only after putting in place appropriate confidentiality undertakings. Notification or even approval requirements may apply to the processing of personal data, depending on the data concerned and the domicile of the data recipient.

For true sale, the acquisition of non-performing loan portfolios is traditionally structured as an assignment of receivables (cesiune de creanţă). This results in an automatic transfer from the assignor to the assignee of all the assignor's rights concerning the assigned receivables together with all the related securities and ancillary rights of the assigned receivables.

There are no available court decisions confirming that given features of the assigned receivables (e.g. enforcement privileges of credit institutions and financial institutions) or the right to accelerate repayment constitute such ancillary rights subject to automatic transfer. In practice, therefore, the assignors of receivables under NPLs accelerate prior to assignment. It can be argued that this uncertainty may be clarified in part by an express provision in the assignment documentation, specifying that ancillary rights, including the right to accelerate payments, are transferred to the assignee of the non-performing receivables.

Whereas the new Civil Code (NCC) which entered into force on 1 October 2011 clarifies and simplifies the rules applicable to assignments of receivables, including the rules concerning the effectiveness of assignments towards the assigned debtors, for opposability purposes towards other third parties, the assignment of receivables under NPLs must still be registered in the Electronic Archive for Movable Securities. Furthermore, to the extent that the assigned receivables are secured and the security over moveable assets has been properly entered into the Electronic Archive for Movables Securities or, in case of receivables backed by security over immovable assets, in the Land Book, respective entries should be amended to reflect the assignment. Such amendments are not very costly and in general should not represent a hurdle for the acquirers of receivables.

While the increasing percentage of non-performing loans to total gross bank loans (mainly due to slow recovery from the 2008 crisis and RSD depreciation, which contributed to overleveraged corporate balance sheets) and the high equity requirements (Core Tier 1 ratio of 12%) imposed on local banks by the National Bank of Serbia (NBS) are expected to drive the Serbian NPL market, a few hurdles need to be overcome for such transactions to materialise.

Potential obstacles that need to be carefully addressed in deal structuring relate mainly to the stringent and inflexible foreign exchange regulations that prohibit a cross-border sale and assignment of receivables. This means that a foreign purchaser can acquire receivables deriving from foreign credit transactions with local borrowers only from a non-resident seller, a scenario that would seem to be relevant for single name (corporate) loans only. On the other hand, only a resident purchaser may acquire local receivables and receivables from a resident lender that are deriving from foreign credit transactions. Accordingly, a local acquisition company needs to be set up in order to acquire local customer receivables.

While FX regulations would seem at first sight to be cumbersome, what is certainly beneficial is the absence of supervision/regulation for Serbian NPL acquisition vehicles, because under Serbian law, neither the purchase nor the servicing and collection of receivables are subject to banking licensing requirements.

For true sale, receivables and ancillary rights are usually transferred by assignment. Under the general provisions, the seller (originator) can assign its receivables by means of an agreement with a third party (e.g., SPV purchaser) and the assigned receivables become the property of the purchaser on execution of the assignment agreement. To the extent that the transaction involves secured loan receivables, however, the transfer of related security (mortgages, pledges, etc.) will be perfected only upon re-registration with the competent registers. In practice this can result in a cumbersome and time-consuming process. In addition, to the extent that the transaction relates to receivables deriving from foreign (cross-border) credit transactions, Serbian FX rules set out that, unless the underlying credit agreement already contained a specific consent to assignment, the respective assignment agreement has to be concluded as a tri-partite agreement involving not only the originating lender and purchaser, but also the debtor of the underlying receivable, who in practice will have little to no incentive to become a party to such a transaction.

Finally, in transaction structuring, the parties will have to consider limitations in relation to banking secrecy and data protection, which are either novel or not tested before the Serbian courts and which, if not addressed adequately during structuring stages, could result in a true impediment to the effective transfer and assignment of receivables, ancillary rights and related security. With respect to defaulting receivables, the NBS' Decision on Risk Management by Banks, which sets out the transfer of defaulted receivables to a local entity unrelated to the bank as a means of credit risk mitigation, could in our view be used as a supporting argument to permit a transfer (banking secrecy rules notwithstanding).

Slovenian law offers banks a variety of alternatives when managing non-performing loans. Depending on the debtor's financial condition, these range from usual debt re-structuring tools, such as enforcement holidays, to forcing borrowers into liquidation. Recently there is also a tendency to stimulate assignments or subrogation of nonperforming loans receivables.

Unlike other jurisdictions, prospective purchasers (other than Slovenian banks) do not need to be concerned about financial services licensing requirements, as factoring is not a licensed activity in Slovenia. On the other hand, factoring companies have to comply with anti-money laundering rules.

If receivables are assigned, accessory rights such as security interests (mortgages, pledges or sureties) or the right to preferential satisfaction transfer to the recipient together with the secured claim by operation of law. Registered security rights such as mortgages and pledges over certain movables, however, will need to be re-registered in the name of the purchaser for the transfer to become legally effective. The necessity to register the change does not affect the priority of the security interest. Depending on the portfolio's size, this time-consuming and costly venture is clearly one of the main challenges for NPL transactions in Slovenia, as documents will need to be translated, notarised and appostilled, and court and notary fees will be charged.

While as in many other jurisdictions an assignment of receivables does not require debtor's consent, limitations arising from banking secrecy and data protection rules are more of an issue. Although credit institutions are permitted to collect, process, and exchange certain information on the credit standing of their customers in an interbank system, such information shall be collected and processed exclusively for managing the credit risk of these institutions. If such data is disclosed to a third party, customer's secrecy interests should be respected, all the more since no legal literature or court decisions are available confirming that in case of NPL transactions the bank's interest to disclosure outweighs a customer's confidentiality interests. Careful structuring will therefore be required to balance compliance with banking secrecy and data protection rules and a prospective purchaser's interest to full disclosure. Customer data may therefore need to be provided in an anonymised manner or on an aggregated basis so that not sensitive information is revealed.

Banks do not enjoy special enforcement privileges. If no out-of-court enforcement has been agreed upon (which is subject to specific statutory requirements), secured claims will need to be enforced under regular enforcement procedures before Slovenian courts and enforcement offices.

The Ukrainian NPL market is dominated by local factoring companies buying loans from Ukrainian banks, where the servicing of the portfolio is sometimes retained by the originating bank. Some Ukrainian banks, however, have started moving portfolios cross border into unregulated SPVs.

It is therefore worth exploring local and cross-border structures. The purchase of receivables by a local company triggers licensing requirements for the local purchaser, because factoring is a financial service which may generally only be rendered by financial institutions. Aside from having to hold a minimum share capital of UAH 3 million (approx. EUR 270,000) or UAH 5 million (approx. EUR 450,000) for factoring companies dealing with individuals' funds, Ukrainian factoring companies must also comply with other requirements, in particular concerning qualified and experienced staff and sufficient technical equipment. While foreign SPVs can be used, this option is only available if it can be argued that the foreign SPV is providing factoring services outside Ukraine. Careful structuring, which will also involve a local debt collection agency or the originating bank as a servicer, and documentation will be required in order to avoid Ukrainian licensing requirements. The purchase price paid by a foreign SPV to the Ukrainian originating bank has to be registered as a foreign investment in Ukraine. Registration will allow the foreign SPV to exchange any receivables collected in UAH into a convertible currency and to withdraw money from Ukraine.

When deciding whether to use a local or foreign purchasing vehicle, the parties should not only focus on regulatory aspects, but should also be aware that a cross-border assignment may trigger the maximum interest rate limitations for cross-border loans, as set by the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU). While the prevailing opinion among practicing lawyers is that these limitations should not be triggered by a cross-border assignment, there is no uniform position of the NBU on this point.

Irrespective of whether a local or a foreign purchaser is involved, banking secrecy must be considered. Up until very recently, Ukrainian banks had to rely to a greater extent on borrowers' consent to transfer/disclose information constituting banking secrecy. The industry concerns were addressed in a recent amendment to Ukrainian banking legislation (in force since 16 October 2011) that expressly permits the disclosure of information constituting banking secrecy to the purchaser of the relevant loan receivable as well as to persons and entities providing services to the bank. At pre-execution/due diligence stages, this allows a structure under which advisors (including legal advisors) are formally appointed by the originating bank, thereby obtaining access to banking secrecy relevant information, and produce reports to an interested party that contain aggregated information only, i.e., without containing sensitive information.

An assignment of receivables and related security can usually be structured as a true sale. Registered security interests can also be validly assigned together with the loan receivables. The form requirements applicable to the assigned security interests have to be followed in the receivables purchase agreement. For example, mortgages are usually notarised, hence the receivables purchase agreement must be notarised too. The transfer of the security interest will only be opposable against third parties upon completion of re-registration of registered security interests. The resultant cost and timing issues are not deal breakers, but will have to be considered when pricing the transaction and when considering deal closing mechanics.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.