This article considers the most common structures employed in Islamic finance and deals with some of the criticisms surrounding its practice.

Introduction

Islamic finance is one of the fastest developing areas of finance which has grown at between 10 to 15 percent annually over the last decade. In addition to Muslim majority states, Islamic finance continues to expand into an increasing number of non-Muslim countries. Over the past decade, legislative reforms have been introduced in several jurisdictions, including major financial centers such as the UK, Hong Kong and Singapore, to place Islamic finance on an equal footing (from a regulatory and tax angle) with its conventional counterpart.

Islamic finance is considered as being a more ethical form of finance and some practitioners have argued that due to the prohibition on gharar (uncertainty) and maysir (speculation) in Islamic finance, its expansion may act as a stabilizing force in times of volatility in global financial markets. Whether this is correct remains to be seen, but it is clear that the

structuring constraints within Islamic finance meant that Islamic banks were less exposed to some of the more speculative forms of investment which led to the 2008 global financial crisis, and were therefore not as severely affected.

So what is Islamic finance and how does it differ from conventional finance? It could be argued that on a practical level, Islamic finance is not different from its conventional counterpart and has the same economic effect as a conventional loan. However, at a conceptual level, the principles and transactions in Islamic finance make it an altogether different form of finance.

As is well known, Shariah prohibits riba (interest) and therefore an Islamic financier cannot simply rent money like a conventional bank.1 The provision of finance in a shariah compliant manner therefore has to enable the financier to earn a return but without charging interest. An Islamic financier therefore makes funds available to its customers by entering into a real underlying transaction; the entry into such transaction forms the basis on which funds are advanced to the customer. In turn, the Islamic financer earns a return by being a party to this transaction, either by charging a profit or mark-up on the sale of an asset, via a profit sharing arrangement or by renting a tangible asset to the customer.

A conventional loan agreement can broadly be divided into five parts; (1) the facility disbursement and repayment mechanics; (2) the yield protection clauses; (3) commercial provisions dealing with warranties, covenants and events of default; (4) syndication provisions; and (5) boilerplate clauses. Of these, Islamic facilities differ only in respect of the first two, and to an extent, the syndication mechanics. The commercial and boilerplate provisions have less to do with shariah principles and are subject to agreement among the parties, and therefore tend to be similar to conventional facilities.

This article, which assumes familiarity with Islamic finance concepts and LMA loan documentation, explores the similarities and differences between Islamic and conventional finance. The discussion below focuses primarily on ijara (lease) and murabaha (cost plus sale) financing structures, being the two most commonly adopted ones in recent years. Other participation based financing structures such as mudaraba and musharaka have become relatively less prevalent following the criticism of the use of fixed price purchase undertakings in such structures by AAOIFI's chairman in 2008 (although they are still used in many IF transactions). The following sections compare the mechanics of an Islamic facility with a conventional loan.

Disbursement and repayment mechanics

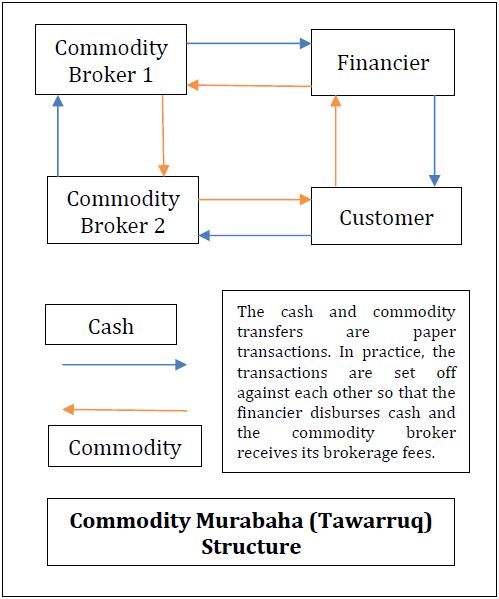

The shariah prohibition on interest necessitates that the Islamic facility must be made available by participation of the customer and Islamic financier in an underlying "transaction", as a consequence of which the financier makes funds available to the customer. This transaction may take the form of a sale (murabaha or tawarruq), a leasing arrangement (ijara), an equity or agency based participation interest (mudaraba, musharaka or wakala) or a procurement contract (istisna or salam). For example, a murabaha transaction involves the financier acquiring an asset for the customer, followed by the sale of the asset to the customer at a pre-agreed mark-up. The financier purchases the asset on spot and sells it to the customer on deferred payment basis. The purchase and sale of an asset or commodity forms the basis on which the customer becomes indebted to the financier. The cost price of the asset is equivalent to principal whereas the mark-up forms the equivalent of interest in a conventional loan. The mark-up is calculated in a manner similar to interest and is indexed by reference to an interest rate benchmark. The tawarruq, a variant of the murabaha, involves the sale and purchase of commodities, with the customer selling the commodity onwards to realise cash. The repayment can be structured by reference to a variable rate with the parties entering into a series of murabaha contracts in succession which roll over the facility on each repayment date. The rate of return on each contract can be fixed on the contract date by reference to the prevailing interest rate benchmark. In practice, the economic effect of such a facility is identical to a conventional loan.

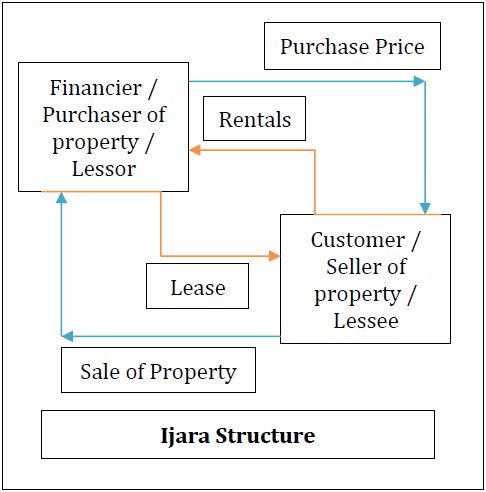

Similarly, in an ijara, the disbursement is structured as a sale and lease back of a tangible asset between the customer and financier. The asset sale enables the disbursement, whereas the leaseback to the customer creates the repayment obligation. Again, the rental payment is divided into a fixed portion, being the equivalent of principal, and a variable element, being the equivalent of interest. The variable rental is usually calculated by reference to an interbank benchmark rate, thus giving the financier the same return as a conventional loan.

Other profit sharing structures such as wakala (agency), mudaraba (investment agency) and musharaka (partnership) involve the provision of finance by the financier to the customer under strict conditions. The customer invests the finance in a venture which helps generate a return. This return is then shared between the customer and financier in a pre-agreed proportion. As a mode of finance, the parties will usually specify an expected return, which is calculated by reference to an interest based benchmark, and any excess is paid back to the customer by way of an incentive fee. Any shortfall in the expected return can be bridged by a liquidity facility, a third-party guarantee, or the build-up of a reserve which can be drawn down as needed in order to ensure the financier always receives the expected return.

Although the disbursement and repayment mechanics of an Islamic facility tend to be very different from conventional loan, the basic operation and effect is the same. In an ijara facility, for example, the customer requests disbursement of the facility by submitting a notice of intent to sell property to the financier. Thereafter parties enter into a purchase agreement whereby the property is acquired by the financier in consideration of the purchase price, being the equivalent of principal in a conventional loan facility. The purchased property is then leased back to the customer, creating a repayment obligation through rental payments.

Similarly, in a murabaha facility, the customer makes a written request to the financier to purchase an asset or commodity on its behalf. The financier thereafter sells the asset or commodity to the customer by issuing an offer notice, which is accepted by the customer, creating a sale contract. A tawarruq involves an additional step whereby the customer sells the commodity to a commodity broker on spot basis to obtain cash. Sometimes the financier will act as the customer's agent and complete both steps on its behalf, and will simply disburse cash to the customer. Like a conventional loan, the repayments in an Islamic facility are structured to ensure periodic principal and interest payments are made to retire the facility.

In terms of disbursement and repayment, an Islamic facility is structured so as to ensure that its economic effect and operational mechanics are, for all practical purposes, identical to a conventional facility.

Prepayment and break costs

Prepayment of Islamic facilities may require, depending on the mode of financing used, careful structuring to replicate the economic effect of a conventional facility. For example, in order to prepay a murabaha facility, the customer must repay the full contract price due at the end of that murabaha period, including the full mark-up (without discounting for early repayment) in addition to the cost price (principal) due on that next repayment date. Such prepayment overcompensates the financier since all of the prepaid amount is not 'due', in a conventional sense, until the end of the murabaha period. The additional amount prepaid is usually refunded by the Islamic financier by way of a discretionary rebate, which ensures that the customer is not worse off under the Islamic facility as compared to a conventional loan. Although the rebate is kept 'discretionary' for Shariah compliance purposes, financiers which fail to give any rebate will risk reputational harm. In case of a partial prepayment, a new murabaha contract, for an amount equal to the outstanding principal (following prepayment), will be entered on the date of partial prepayment, which amount is then rolled over for a new murabaha period.

In addition, depending on the Islamic financier's shariah board, some banks will deduct break costs from the rebate amount, whereas other shariah boards do not allow such deduction as it is compensation linked to cost of funding. The latter interpretation is more consistent with the principles of shariah, given that the deduction of 'opportunity and funding costs' have been unanimously rejected by shariah scholars.

Under an ijara facility, voluntary prepayment is structured as a repurchase of part of the leased asset by the lessee pursuant to a sale undertaking granted by the lessor. A mandatory prepayment takes the form of a forced sale of the asset by the lessor to the lessee under a purchase undertaking granted by the lessee. The lessor, however, continues to retain 'ownership' of the asset, which will be transferred once all lease payments are completed. The purchase undertaking is exercised at a certain exercise price, which is calculated so as to be equivalent to the outstanding principal and interest.

Given that the lease rental is fixed at the beginning of each rental period, additional costs cannot be added during the tenor of the lease. Break costs may, however, be included as an additional cost payable to the lessor on account of the lessor's added administrative burden of dealing with an unscheduled repayment. They can also be added to the variable rental payable in the next rental period. The financier may also recover break costs as a prepayment fee. Where break costs are recovered via a prepayment fee, they are likely to overcompensate the financier. However, as noted above, most shariah scholars do not favour the recovery of costs related to funding of the facility.

Yield protection clauses

In conventional facilities, yield protection clauses ensure that the lender receives its expected rate of return by making the borrower responsible for any additional costs or taxes (excluding corporate income tax payable by the lender) which may become payable in connection with the facility. Like their conventional counterparts, Islamic financial institutions do not like to see their yields squeezed by such costs or taxes, and will build in protections to pass such costs on to the customer.

Increased costs

Like conventional loans, customers of Islamic banks are required to indemnify the bank against any increased costs incurred by the financier, provided such costs are incurred due to the provision of the facility. Whereas conventional loan documentation will require increased costs to be reimbursed on demand, increased costs in an Islamic facility can only be charged as part of the profit or rent and added to the next murabaha contract period or lease period. This is because a murabaha contract or a lease is a fixed contract whereby the purchase price or rent is agreed upfront; the financier cannot charge additional sums during the term of the contract. Where the increased cost arises in the last lease period, the amount may be added to the exercise price under the purchase undertaking payable at maturity.

Tax gross up and indemnity

Islamic facility documents will also typically require the customer to ensure that all repayments are grossed up so that the financier receives the amount it would have received if no tax deduction was made. Any gross-up amounts or indemnity payments will be added to the mark-up / profit or rent payable in the following murabaha or ijara contract period.

Since a murabaha is a fixed price contract and the cost price and mark-up cannot be increased during the term of the contract, any additional amounts payable such as increased costs or tax indemnity must be included in the mark-up for the next murabaha contract.

Indemnity payments (such as increased costs or tax indemnities) are sometimes drafted as repayable on demand, but this approach goes against the grain of the underlying transaction and ideally these costs should be added at the next cycle, if any, or to the termination payment.

Ownership taxes under ijara

Under an ijara facility, a financier, as owner of the leased asset, becomes liable to pay certain taxes related to ownership which cannot be passed on to the lessee under shariah principles. In addition, the owner is responsible for insurance and major maintenance costs related to the leased assets.

Since the Islamic financier does not wish to be responsible for these additional costs, in practice, these costs are paid by the lessee as service agent for on behalf of the lessor, and are then set off against supplemental rentals charged to the customer in the next rental period.

Default interest or late payment fees

The Islamic equivalent of default interest in a conventional facility is a "late payment charge" calculated as a percentage of the outstanding amount. Some scholars take the view that the amount must be fixed and cannot be a percentage of the outstanding facility. A late payment fee is permissible in Islamic facilities provided it is 'intended' as an inducement to the customer to make timely repayments. The fee cannot be charged as additional compensation to the financier on account of the greater risk of servicing a loan in default. The Islamic financier may only deduct its actual costs (excluding funding and opportunity costs) from such late payment fee, and donate the remainder to a charity approved by the financier's shariah board.

Market disruption

Where a profit rate or lease payment is linked to a benchmark rate, market disruption provisions must be included to enable the parties to determine the applicable rate in case the benchmark rate for that currency and period is no longer available. In these cases, a conventional loan would include a number of standard fallback provisions such as an interpolated or reference bank rate, failing which banks would charge the borrower its cost of funds. These provisions are likely to violate the Islamic prohibition against uncertainty since it may not be possible to determine an interpolated or reference bank rate either. Further, given the difficulty of calculating the 'cost of funds' for an Islamic bank (which raises funds in the interbank market through a combination of murabahas and mudarabas or other profit sharing arrangements), the Islamic financing documents will typically specify a fixed profit or rental amount in case a market disruption event occurs.

Syndication of Islamic facilities

Unlike a conventional facility where the agency and security agency provisions are set out in the facility agreement itself, the syndication provisions in an Islamic facility are contained in a separate investment agency (mudaraba) agreement.

It is impractical for each member of an Islamic syndicate to separately enter into an underlying "transaction" with the customer(s) in order to make the Islamic facility available. Accordingly, syndicated Islamic facilities are structured so that one institution, acting as the investment agent, enters into the underlying Islamic transaction with the customer, and that agent then enters into a back to back investment agency arrangement with the syndicate. The investment agent receives funds from the syndicate under the investment agency agreement, and thereafter invests these proceeds via a bilateral Islamic facility with the customer. Unlike a conventional syndicated facility, the syndicate members in an Islamic facility do not have a direct relationship with the customer and must, in the case of a default, rely on the investment agent to enforce its rights and pass through any recovered amounts. This makes Islamic lenders particularly vulnerable to bankruptcy risk of the investment agent.

In general, the rights and protections given to the investment agent are similar to a facility or security agent under a conventional facility.

Are Islamic facilities more than window dressing?

Although Islamic facilities require careful structuring to ensure compliance with shariah principles, the economic return and allocation of risk in an Islamic facility is substantially similar to a conventional facility. Islamic financing documents mimic conventional documents and try to reconcile shariah concepts with the framework of a conventional facility.

Despite the above similarities, there are some material respects in which Islamic facilities differ from conventional ones.

First, irrespective of the jurisdiction in which the Islamic facility is made available, Islamic facilities cannot (for shariah reasons) be structured to charge the equivalent of compound interest.

Islamic facilities require tangible assets as part of the financing transaction, making it generally difficult to enter into highly speculative and uncertain transactions.

It is argued that Islamic financiers also assume greater risk compared to conventional banks, thereby justifying the sometimes higher pricing of Islamic facilities. In a murabaha facility, for example, the financier assumes a risk of fall in commodity prices between the time of purchase and resale. This risk is minimised as the commodities are held by the financier only momentarily, but in times of price volatility could pose an issue. In an ijara, the Islamic financier assumes the risk of ownership, and total loss, of the leased asset. A total loss (with no fault on the part of the customer) will discharge the customer from any further payment obligations towards the financier. Although the financier's risk can be mitigated through insurance, the financier still faces the risk that the insurance proceeds may be insufficient to repay the facility in full. In such event, the financier will have no further claim against the customer, except perhaps an indemnity claim if the customer has failed to procure adequate insurance (as services agent of the financier).

A default under an Islamic facility tends to pose its own set of challenges. In a murabaha facility, Islamic financiers cannot continue to accrue mark-up/profit on the outstanding sums (once a default has occurred and the facility is accelerated) unless the customer and financier continue to enter into new murabaha contracts for subsequent periods. A late payment fee is usually a fixed amount and will not cover missed mark-up or rental payments. In such circumstances, the amount payable under the murabaha contract becomes fixed and cannot be increased on account of the delay in payment. In an ijara, once the purchase undertaking is exercised, the amount payable by the customer becomes fixed and cannot be increased by charging further rentals. Any loss suffered by the bank on account of delayed payments may only be recovered by way of an indemnity claim. Further, an Islamic bank cannot keep late payment fees (equivalent to default interest) charged to customers and must pay such amounts (after deducting expenses) to a charity approved by its shariah board.

Finally, Islamic financiers can only transact with businesses or invest in assets that are shariah compliant. Therefore, Islamic financial institutions cannot lend to entities or businesses involved in the production or consumption of alcohol, pork, gambling, armaments or pornography, or in any other socially harmful or unethical venture which is repugnant to the principles of shariah.

Conclusion

For the most part, the risk and reward in an Islamic facility is substantially similar to a conventional facility. Critics therefore argue that the underlying transaction, whether an ijara, murabaha or any other, only serves to whitewash an otherwise prohibited interest based arrangement.

Shariah scholars have responded to this criticism by arguing that even though the risk and reward of an Islamic financier is similar to that of a conventional lender, the manner in which this return is earned is halal. It is argued that in a murabaha transaction, for example, the Islamic financier takes the risk of a fall in commodity/asset price, albeit momentarily, by purchasing and selling the assets to the customer, thus being entitled to a return on the trade. In the context of an ijara, it is argued that the Islamic financier takes the risk of ownership of the leased asset, the rent being its compensation for taking such risk. They argue that mere fact that profit or rent is calculated by reference to an interest rate benchmark does not make the transaction un-Islamic.

Islamic financing techniques were developed in medieval trading societies, within the framework of the shariah prohibition on interest, to facilitate commerce and trade. The financier therefore acted as partner or trading counterparty, and shared some of the risk, thus justifying the payment of a return from the venture. Whether contemporary Islamic financing techniques, which seek to mimic conventional loans, do justice to the principles of shariah is still a matter of debate amongst scholars and practitioners.

However, given the commodification and standardization of today's loan markets, it is perhaps impractical to assume that Islamic banks will be able to operate based on non-standardized and non-benchmarked rates of return; Islamic banks cannot be expected to act like private equity providers. Reconciling the principles of shariah with modern banking is a balance which will continue to fuel further innovation in this area, perhaps bring Islamic finance ever closer to the underlying ideals of shariah.

Footnotes

1 There is a minority view of Islamic thought which considers the prohibition on riba as being limited to excessive interest. Existing Islamic finance documentation is based on the assumption that interest is prohibited in all its forms. This article therefore follows the majority view.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.