Strengthening Intellectual Property Rights to Protect Innovators and Creators in Nigeria1

"It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is the most adaptable to change, that lives within the means available and works co-operatively against common threats."

"In the struggle for survival, the fittest win out at the expense of their rivals because they succeed in adapting themselves best to their environment." – Charles Darwin [1859]

Primer: Charles Darwin2 posited that species survive and propagate themselves not by virtue of sheer strength or intelligence but based on their ability to adapt to their surroundings. This ability to be flexible and to fluidly navigate our environment underscores all human dealings and behaviour.3 To bring this home to this audience in relation to intellectual property law and practice, we live in a world that is sentient, from our surrounding environment to the manner in which we interact with others and how we get our daily tasks accomplished. We are at a pivotal moment in human history and about to witness an exponential growth in technological interconnectedness and the interoperability of intelligent machines animated by computer algorithms and software programmes. In the not-too-distant future, the world as we know it may become unrecognisable. The seamless interactions between our smart devices and wearables, the automation of our daily chores, and the provision of legal services will soon become irrevocably altered via technology. Anyone who is paying close attention to these trends would be wise to prepare to meet them and that preparation is what sets one individual/professional/nation apart from the crowd.4

It takes consistent hard-work, contemplation, effective planning and a clear vision of the intended objective to remain relevant. A good starting point is to have a clear vision of what we wish to accomplish as a nation and if I may be so bold, as a developing country we obviously would want to become a developed nation. How we attain our developmental goals is directly proportional to our level of industrialisation. To become industrialized, we must acquire the skills-set, the technological tools and innovation in order to do so. Acquisition of the requisite skills-set, technological tools and innovativeness can either be home grown or imported, or a combination of these methods. Whichever way we decide to accomplish this, we would need to encourage those creators and innovators who will drive our quest for industrialisation. One very effective way of encouraging our innovators is by recognising and strengthening the IP regime in the country. To do this, we need to ensure that our laws are compliant and up to date, user friendly and easily enforceable within the framework of an efficient administrative structure.5

"Africa has a great tradition of innovation and creativity...and innovation is a central driver of economic growth, development and better jobs. It is the key for firms to compete successfully in the global marketplace...Intellectual property is an indispensable mechanism for translating knowledge into commercial assets – IP rights create a secure environment for investment in innovation and provide a legal framework for trading in intellectual assets."6

International Trade, Development and Intellectual Property: In an increasingly globalised world, the interdependence of human activities and actions are even more pronounced and deserving of focused attention. Within this framework, the relationship between international trade, development and IPRs must also be recognized and harnessed to enable the country to attain its developmental objectives.7 Whilst we have underscored the connection between development and IPRs, we also need to objectify the role of international trade as the bedrock upon which they operate and development as the outcome of that interaction.

The relationship between these three was properly articulated under the auspices of the WTO and its appendant instrument, the TRIPS Agreement.8 The integration process was justified on the basis that the proliferation of infringing and pirated products negatively interferes with access to legitimate ones and constitutes a barrier to trade and that unduly burdensome registration formalities and approval requirements hinders trade and investment and stalls IP transfer agreements.9 Under the TRIPS Agreement member states are expected to address the following minimum requirements for ensuring compliance with their obligations under the WTO arrangement: a) compliance with a set of minimum standards within national IP laws b) institution of minimum criteria for national enforcement of IP rights through civil, criminal and administrative processes c) subjecting the resolution of IP disputes to the WTO dispute settlement system and d) compliance with common procedural requirements for the administration and maintenance of IP rights.10

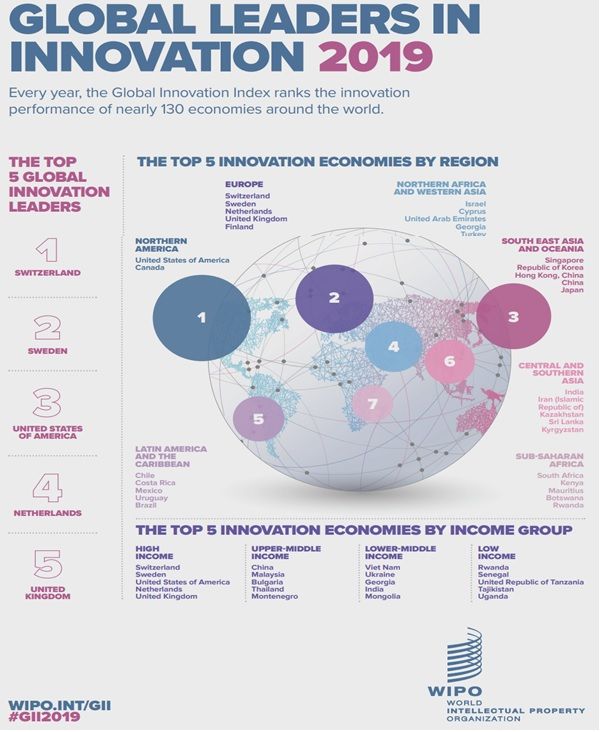

What Other Developing Countries are Doing: A good indication of how various countries are faring vis-à-vis technological innovativeness and intellectual property recognition and protection is mirrored in the annual Report on the Global Innovation Index (GII), published by WIPO.11 In the 2019 edition of this report, Nigeria moved up two notches to the 116th position in the world ranking but still lags behind other African countries regarded as more innovative and presumably that adopt stronger and more effective mechanisms for IPR protection and enforcement.12 Within the sub-region South Africa (63rd),13 Kenya (77th)14 and Mauritius (82nd)15 came out tops in this year's rankings, followed by Botswana (93rd), Rwanda (94), Senegal (96th) and Tanzania (97th). Although the report notes that sub-Saharan Africa performs relatively well on the innovation index with more African economies among the group of innovation achievers than any other region in the world since 2012, Nigeria was categorized as one of the countries that is underperforming based on its level of development.

By contrast, Singapore which is ranked 8th in the 2019 rankings received the following review:

"Singapore aims to be a center of innovation and a key node along the global innovation supply chain where innovative firms thrive on the basis of intellectual property and intangible assets. To achieve this ambition, one strategy is to strengthen Singapore's innovation ecosystem by helping enterprises to innovate and scale up. Singapore envisages advancing its conducive environment, international linkages, capabilities in intangible asset management, IP commercialization, and skilled workforce. In 2016, the Government of Singapore committed US$14 billion for research, innovation, and enterprise activities. It identified four strategic domains for prioritized research funding: (1) advanced manufacturing and engineering, (2) health and biomedical sciences, (3) services and digital economy, and (4) urban solutions and sustainability. The Intellectual Property Office of Singapore (IPOS) has also transformed to better serve global innovation communities by conducting regular reviews of Singapore's IP policies and building capabilities in intangible asset management and IP commercialization, including IP skills."16

[Culled from the WIPO website: https://www.wipo.int/export/sites/www/global_innovation_index/pdf/gii19_leaders_infographic.pdf]

What Nigeria Should be Doing: Within the context of adaptation for survival, there are a couple of immediate initiatives the country should be seriously invested in, like ensuring that our basic/enabling laws are brought up to date and in step with global trends as much as practicable. This forms the framework upon which other proactive initiatives can be superimposed.17 The next step is to articulate national innovation/IP policy goals and objectives, milestones and a clearly identifiable plan of action.18 This should form part of the national development policy along with other initiatives like the science and technology policy, the telecommunications policy,19 the education policy etc. One of the ways to advance effective policy goals is to set up a specific commission or agency charged with the responsibility for addressing the challenges in each sector. A good example is the Nigerian Copyright Commission (NCC) which has accomplished several milestones in the Copyright sector.20 The IPCOM bill which has been pending now for a couple years before the legislative houses was meant to establish an industrial property commission to pursue certain sector-specific goals like the NCC does for the copyright industry.

Next is the necessary empowerment of these agencies with the requisite tools and funding to enable them to achieve their designated goals.21 Having underscored the fact that IPRs are the driving force behind our industrialisation, innovation and development aspirations, there's a need to design a systematic process for teaching, training and supporting our creators and innovators, providing the necessary funding through the public and private sectors, providing legal support for the protection and enforcement of IPRs.22 Part of these initiatives involve the training of law students, lawyers and judges on the fundamentals of IP law and enforcement, and on the drafting of statutes in the IP sector.23 Finally, the collaboration of the various agencies of government with a bearing on innovation and development is vital in achieving our national goals in the near and long-term.24 Whilst individually these agencies are undoubtedly doing their very best based on the resources at their disposal, the absence of cross pollination and deep collaboration takes away from the positive accomplishments that are feasible.

Much like the importance of regional integration as a tool for economic growth nationally and within the sub-continent, regional IP organisations are designed to leverage on the unique strengths and weaknesses of member nations to advance our common economic goals.25 It is time to re-consider our position regarding membership of these groups as well as participation in the Madrid system for the international registration of trademarks.26 Other initiatives instituted or contemplated by the African Union like the NEPAD27 and the PAIPO28 deserve closer examination with a view to identifying areas of mutual collaboration and partnerships in the sciences, technology and innovation (STI) fields.

Having largely addressed the topic as framed by the organizers of this event, I must not fail to point out that as a developing nation, there is a need to tailor our IPR system to facilitate our economic and developmental objectives based on our peculiar needs.29 Merely strengthening our IPR system for the sake of global acceptance is bound to stunt our growth and prolong the turnaround time for industrialisation.30 I have addressed the fact elsewhere that stringent IPR laws and institutions even though this may have some salutary effect on our creatives, may also conversely interfere with the development of an enduring innovative culture and the technological advancement of the nation by impeding the much needed access and collaboration required for sustained economic growth.31 A brief look into the annals of time will disclose that the current advanced economies thrived on a relaxed IPR system in order to spur the growth of their local enterprises and innovators, introducing more stringent regulations after they had achieved solid growth in nation building backed by the strong multinationals which they fostered and nurtured.32 Although we do not recommend blatant violation and the illegal appropriation of foreign IPRs, we need to borrow a leaf from this strategy and introduce necessary adjustments to our IP laws and regulations to facilitate our industrialisation process.33

Concluding Remarks: Whilst as a nation, we do need to strengthen intellectual property rights to protect and incentivise creators and innovators,34 we also need to be conscious of the very real possibility of creating the opposite effect when we do not balance those interests with public interest needs and in consonance with the country's developmental trajectory. Consequently, we need to pay closer attention to matters that are of unique interest to us as a civilisation, e.g., matters having to deal with biotechnologies, traditional knowledge and the unique expressions of our folklore. In order to stave off the ill-effects of globalisation and the sometimes negative impact of international trade on developing economies, we need to take advantage of the beneficial effects of regional trade through regional integration and participation at various levels.35 It is necessary to set up a committee to review the nation's IP laws and policies every few years to evaluate their relevance to the overall economic and development objectives of the country. The products and knowledge base of certain vital agencies like NAFDAC and NOTAP etc., should be properly harnessed and objectified for nation building. In the field of patents, we need to assemble technology experts and scientists to review and examine patent applications for usefulness and patentability. It is also necessary to establish a funding pool for supporting promising innovations and for commercializing these ideas and creations.

Source: UNCTAD Report https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/aldcafrica2019_en.pdf36

Some scholars argue that getting the balance right between the competing interests highlighted above involves ensuring that the costs imposed by the conferment of monopoly rights do not exceed the benefits of the anticipated new knowledge and ideas thereby generated.37 Some ostensible solutions include the reduction of terms of protection in some cases for certain IPRs, raising the originality bar for patents and some other traditional fields and facilitating the utilisation of compulsory licenses and parallel imports as appropriate in the national interest.

"...the foundation of economic development is the acquisition of more productive knowledge. The stronger the international protection for IPRs is, the more difficult it is for the follower countries to acquire new knowledge. This is why, historically, countries did not protect foreigners' intellectual property very well (or at all) when they needed to import knowledge. If knowledge is like water that flows downhill, then today's IPR system is like a dam that turns potentially fertile fields into a technological dustbowl."38

Footnotes

1 John C. Onyido, Esq., Partner and Head Intellectual Property & Technology Department, SPA Ajibade & Co., Lagos, Nigeria. Paper delivered to Law students University of Abuja, 18th September 2019.

2 [1809 – 1882] On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, 1859.

3 In the struggle for resources, the principle of natural selection explained why some species thrived while others floundered. "...specifically, what Darwin saw was that all organisms competed for resources, and those that had some innate advantage would prosper and pass on that advantage to their offspring. By such means would species continually improve." Bill Bryson, A Short History of Nearly Everything, Broadway Books, New York 2003 p. 384.

4 A good example of adaptation in the legal profession relates to the integration of new forms of technologies in professional services delivery and in meeting the evolving needs of clients in efficient and cost-effective manner. See generally, John Onyido: GUARDIAN NEWSPAPER interview of 1st January 2019, pp. 29-31, available at https://m.guardian.ng/features/law/rules-on-professional-advertising-are-too-rigid-and-formalistic/ accessed 12th September 2019.

5 Several of our local IP laws are badly in need of revision and significant overhaul. There are currently several bills awaiting legislative review prominent among which are: the IPCOM Bill, the proposed Trade Marks Bill and the Copyright Bill, respectively.

6 Francis Gurry, WIPO Director General, being part of a speech delivered at the African Ministerial Conference, November 2015.

7 See John Onyido, "Teaching Intellectual Property Law as a Pedagogical Imperative in the Faculty of Law University of Ibadan", Nigeria 2018, p. 14.

8 Annexure 1C to the WTO Agreement.

9 Mitsuo Matshushita et al, World Trade Organisation: Law, Practice and Policy, 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, 2006.

10 Ibid., at p. 705.

11 In collaboration with INSEAD and Cornell University (S.C. Johnson School of Business).

12 Global Innovation Index, 2019 with the theme: Creating Healthy Lives – The Future of Medical Innovation, available at file:///C:/Users/johnc/Desktop/Global%20Innovation%20Index.wipo_pub_gii_2019.pdf, accessed 10th September 2019.

13 But see Sharon Dell, "South Africa: Intellectual Property Rights Failing", University World News, July 2011 available at: https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20110715165939648, accessed 15th September 2019 (arguing that the South African IPR regime is not supporting the national system of innovation sufficiently but appears to unwittingly facilitate exploitation by foreign interests). See also Jonathan Berger and Andrew Rens, "Innovation and Intellectual Property in South Africa: The Case for Reform" available at: http://ip-unit.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Innovation-IP-in-SA.pdf, accessed 15th September 2019 (pointing out that the non-examination system and the questionable quality of registered inventions under the South African Patent regime is partly responsible for the marginal protection of locally issued patents in foreign jurisdictions). In May 2018, South Africa came up with a new policy to improve access to medicines. See South Africa adopts new IP policy improving access to medicine, available at: https://unctad.org/en/pages/newsdetails.aspx?OriginalVersionID=1762&Sitemap_x0020_Taxonomy=UNCTAD%20Home;#1535;#Intellectual Property (IP);#2248;#Impact Story (UNCTAD in its report underscored the fact that, "The purpose of IP policy is to guide policy makers on how to use intellectual property to promote certain domestic development objectives, such as innovation, technology transfer and industrial development.")

14 See Justus Wanzala, "Kenya Takes Steps to Enhance Intellectual Property Awareness", Intellectual Property Watch, 2016 available at: https://www.ip-watch.org/2016/01/12/kenya-takes-first-steps-to-enhance-intellectual-property-awareness/, accessed 15th September, 2019 (reviewing the terms of reference of a specialized Board to guide the activities of the Kenya National Innovation Agency (KNIA) through the creation of awareness about IPR related matters and introducing a collaborative atmosphere among varied technological innovations through incubation initiatives and the diffusion of technical know-how). See also Patricia Kameri-Mbote, "Intellectual Property Protection in Africa: An Assessment of the Status of Laws, Research and Policy Analysis on Intellectual Property Rights In Kenya", IELRC Working Paper 2005-2 available at: http:www.ielrc.org/comntent/w0502.pdf (questioning the extent to which Kenya's IP laws and institutions have contributed to its national development, while pointing out that the linkages between IPRs, endogenous technological know-how and inventive capacity are still lacking).

15 With the recognition of the importance IPRs to economic and social development, the government of Mauritius developed an Intellectual Property Development Plan (IPDP) in collaboration with WIPO to ensure that stakeholders, law enforcement, users and generators of IP have the requisite know-how and necessary capacity to utilise IP as a tool for promoting innovation, research, investments and economic growth. See the IPDP of Mauritius, available at http://www.mauritiustrade.mu/ressources/pdf/IPDP-FINAL-REPORT-2.pdf. And see Le Mauricien, "World Intellectual Property Day – Mauritius Still Has a Lot to Catch Up!" available at https://www.lemauricien.com/article/world-intellectual-property-day-mauritius-still-has-a-lot-to-catch-up/, accessed 14th September 2019 (urging for the recognition of the human development aspects as an essential component of the country's IP objectives and the need to tailor local laws to suit the needs and aspirations of the country). See also "Mauritius Aligns Intellectual Property Incentives with Nexus Approach", Ernst & Young Global Tax Alert, June 2019, available at: https://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/EY-mauritius-aligns-intellectual-property-incentives-with-nexus-approach/$FILE/EY-mauritius-aligns-intellectual-property-incentives-with-nexus-approach.pdf, accessed, 14th September 2019.

16 Global Innovation Index 2019, supra, at p. 22.

17 John Onyido, "You and IP Law: The System that Promotes Innovation and Creativity", Paper delivered to the law students of the University of Benin, Nigeria 2018. [Available on file with author].

18 Ibid.

19 See the National Broadband Plan (2013-2018) for the Telecoms sector, available at: https://www.researchictafrica.net/countries/nigeria/Nigeria_National_Broadband_Plan_2013-2018.pdf, accessed 13th September 2019.

20 Under section 34 of the Copyright Act Cap C28 LFN 2004, the Commission is responsible for overseeing all matters affecting copyright in the country, monitoring, supervising and advising government on Nigeria's position in relation to its international treaty obligations, public enlightenment, maintaining a databank of authorship etc. Over the years the NCC has embarked on numerous enforcement raids and enforcement actions to discourage and deter piracy and counterfeiting. It has also spearheaded the revision of our copyright laws specifically in 1988, 1992 and 1999, respectively, as few examples.

21 See Adejoke Oyewunmi, Nigerian Law of Intellectual Property, University of Lagos Press (2015/2019) pp. 15-19, for a brief review of the statutory and institutional framework for the Administration of Intellectual Property rights in Nigeria.

22 Sope Adegoke, "Intellectual Property Rights in Sub-Saharan Africa" 2011 p. 53, available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/289, accessed 11th September 2019.

23 See generally, John Onyido, "Teaching Intellectual Property Law as a Pedagogical Imperative at the Faculty of Law of the University of Ibadan, Nigeria", op. cit. (n. 7).

24 See for instance, The Trump Administration's Annual Intellectual Property Report to Congress, developed by the Office of the U.S. Intellectual Property Enforcement Coordinator, bringing together coordinated efforts of the White House, the Departments of Commerce, Justice, Homeland Security, State, Treasury, Health and Human Services, and Agriculture, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, and the U.S. Copyright Office. The IPEC Annual Intellectual Property Report 2019 is available here: file:///C:/Users/johnc/Desktop/IPEC-2019-Annual-Intellectual-Property-Report-to-Congress%20(1).pdf (the report recognises that for the US IP and innovation policy objectives to be successful it must recognize and include the collaborative efforts of all branches of government, the private sector and international partners).

25 The African Continental Free Trade Agreement (ACFTA) signed in Kigali, Rwanda in 2018 is a vital regional trade agreement that portends great potentials for the continent. Nigeria and South Africa the biggest economies in the region only ratified the agreement following months of executive reluctance. In the field of IP regional bodies include ARIPO and OAPI, for English and French-speaking African countries respectively.

26 The Madrid Agreement Concerning the International Registration of Trademarks concluded 1891 and the Protocol of 1989 as amended November 12th 2007, available at: file:///C:/Users/johnc/Desktop/MadridProtocol.trt_madridp_gp_001en.pdf, accessed 11th September 2019.

27 The New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD) was established by the African Union at its inception. Its expert group on science, technology and innovation launched the ASTII in 2007 and an Observatory of Science, Technology and Innovation Strategy for Africa in 2011.

28 The AU also toyed with the idea of creating a Pan-African Intellectual Property Organisation (PAIPO) to promote the harmonisation of the IPR systems of member states, instigate measures that would assist member states to fight piracy and counterfeiting utilising their respective IP systems, effectively focusing the African common position on IP matters (on genetic resources, geographical indications, biological diversity and expressions of folklore), and assisting in developing and channelling the African IP position at international negotiations. This proposal appears to have been shelved in favour of closer collaboration with WIPO.

29 See Willem Pretorius, "TRIPS and Developing Countries: How Level is the Playing Field?", in Global Intellectual Property Rights: Knowledge, Access and Development (eds. Peter Drahos and Ruth Mayne), Oxfam 2002 pp. 183-97.

30 Ha-Joon Chang, Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism, Bloomsbury Press, New York 2008 pp. 122-144.

31 John Onyido, "You and IP Law: The System that Promotes Innovation and Creativity", op. cit., at p. 4.

32 "The historical picture is clear. Counterfeiting was not invented in modern Asia. When they were backward themselves in terms of knowledge, all of today's rich countries blithely violated other people's patents, trademarks and copyrights. The Swiss 'borrowed' German chemical inventions, while the Germans 'borrowed' English trademarks and the Americans 'borrowed' English copyrighted materials – all without paying what would today be considered 'just' compensation." Ha-Joon Chang, supra, at p. 134. On the historical justification for the use of protective measures by developing economies see, John Onyido and Bolaji Gabari, "International Trade under the GATT/WTO Multilateral Regime vis-à-vis Developing and Least Developed Economies: Spotlight on Nigeria", in A Review of Contemporary Legal Trends in Nigerian Law, LexisNexis 2017, pp.166-68.

33 The developed countries led majorly by the United States have been steadily extending the terms of protection for IPRs globally utilising the world trading platform. In the 1790 US Copyright Act, the term of protection was 14years renewable for a further 14-year period. The US Copyright Term Extension Act has since extended that to life plus 70 years for individuals and 95 years for works of corporate authorship from the terms set under the 1976 Act (i.e., life plus 50 and 75 years, respectively). For patents, the term of protection has since gone from 14 years to 20 years, when the global average used to be around 16-17 years between 1900 and 1975. As though entrenching these higher protection terms in the WTO-TRIPS Agreement was insufficient, the US is currently pursuing even longer protection terms through the instrumentality of bilateral trade agreements in the de facto extension of patents over pharmaceuticals. Since monopoly rights impose significant social costs on the society, it is important to ensure that the extended periods are justifiable in terms of engendering new knowledge and innovations.

34 See generally, Edgardo Buscaglia, "U.S. Foreign Policy and Intellectual Property Rights in Latin America", available at: https://www.hoover.org/research/us-foreign-policy-and-intellectual-property-rights-latin-america, accessed 17th September 2019. (the U.S. ties IP issues to its foreign policy).

35 See Patrick Terroir, "A New Look At Intellectual Property and Innovation in Africa", available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2822360, accessed 16th September 2019 (reviewing the emerging signs of a true IP system as including the mobilisation of the continent for innovation through the efforts of the African Union and NEPAD and secondly through the framework of a serious IP infrastructure in terms of the regional IP bodies). Other emerging new practices are the introduction of Open Innovation initiatives (like OPENIX: http://.theinnovationhub.com and OPEN AIR http://www.openair.org.za,) the use of compulsory licensing and medicine patent pools to assist in the creation of manufacturing capacity for pharmaceuticals and the production of generics, like the Medicine Patent Pool (MPP) http://www.medicinepatentpool.org. See generally, Innovation & Intellectual Property: Collaborative Dynamics in Africa (eds. Jeremy de Beer et al) UCT Press, 2014.

36 The UNCTAD Economic Development in Africa Report, 2019.

37 See Dean Baker et al, "Innovation, Intellectual Property, and Development: A Better set of Approaches for the 21st Century" (Access-IBSA), 69, available at http://ip-unit.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/IP-for-21st-Century-EN.pdf, accessed 16th September 2019.

38 Ha-Joon Chang, supra, at p. 142.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.