This paper examines trends and developments in cross-border transactions, both from a Canadian and U.S. perspective. It begins with a review of transaction statistics and commentary by the author, based on his experience as President of M&A International Inc., a leading mid-market investment bank with over 600 professionals in 42 countries. The statistics (which are based on data from S&P Capital IQ) and commentary have been updated from what was presented at the ASA-CICBV Conference in October 2014 to incorporate year-end 2014 information.

This paper also examines the potential benefits, risks and challenges of cross-border transactions. It concludes with a discussion of some of the key considerations for buyers contemplating a Canada-U.S. cross-border transaction. The author would like to thank Stephanie Lau, Analyst at Veracap M&A International Inc. for her assistance with this paper.

A Global Perspective

As a starting point, it is helpful to take a global perspective on transactions. As indicated in Exhibit 1, there were about 44,000 M&A transactions reported in 2014, which represents a slight decline from the previous year. However, aggregate transaction value was close to U.S. $2.7 trillion, representing the highest level since 2007. It is important to note that values are not disclosed for more than 50% of transactions. This is particularly the case for smaller and mid-size deals involving privately-held companies.

Exhibit 1

For transactions where values were reported, the vast majority (approximately 72% in 2014) had a value of less than US$50 million. Less than 5% of transactions were consummated for a value in excess of US$500 million (see Exhibit 2). This is within normal parameters. The median transaction size in 2014 was just under US$15 million, which reflects the continuation of an upward trend that began in 2010. As noted above, given that the value of many smaller transactions is not reported, the true median transaction value is likely lower.

Exhibit 2

The financial services sector was once again the hottest sector, accounting for 28% of transactions in 2014. Other popular sectors (each of which accounted for more than 10% of total transactions in 2014) included consumer discretionary, industrials and information technology (see Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3

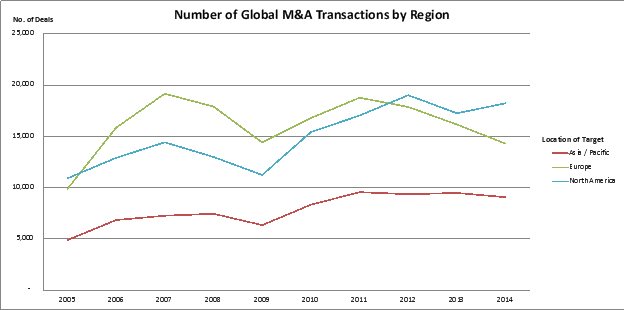

On a regional basis, North America accounted for the largest number of transactions, based on the location of the target company (Exhibit 4). The number of transactions involving European targets continued to decline, likely due to THE suppressed economic environment in that region. Asian companies were represented the fewest number of target companies. This is partly explained by regional cultural differences, whereby many owners of Asian-based companies prefer to transition their business to family members, or they do not disclose that a sale has occurred.

Exhibit 4

A U.S. Perspective

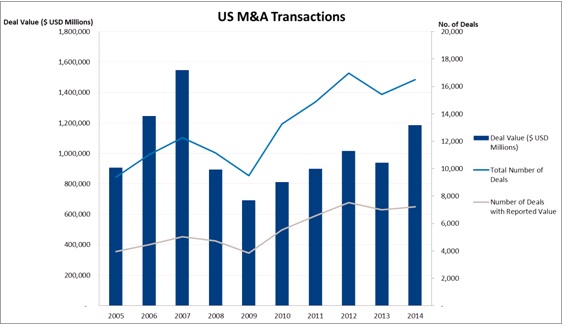

2014 was a strong year for M&A activity in the U.S. The value of transactions amounted to almost $1.2 trillion, representing the highest level since 2007 (see Exhibit 5). The number of transactions was also near a record high, only being surpassed by 2012 (which was inflated as many sellers expedited the sale of their business to avoid tax changes that came into effect in 2013).

Exhibit 5

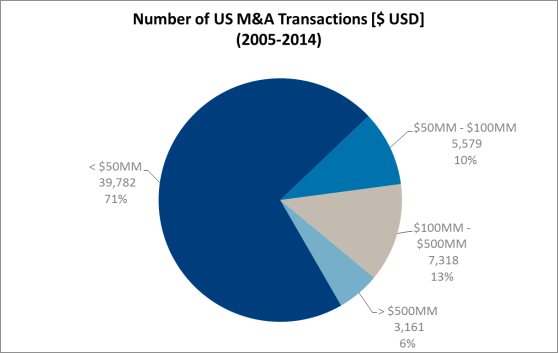

In terms of transaction size, over the past 10 years, approximately 71% of transactions with reported values in the U.S. have been for less than US$50 million, while about 6% are in excess of US$500 million (see Exhibit 6). The median transaction value in 2014 was US$16.3

Exhibit 6

The large majority (approximately 95%) of U.S. companies sold in any given year are privately-held. In fact, there were only 392 U.S.-based public companies sold in 2014, representing the second lowest level in the past 5 years (Exhibit 6). The takeover premium (measured as the price paid for the acquired shares vs. the trading price of those shares one month prior to the announcement) declined to 28%. The low number of transactions and takeover premiums are likely the result of buoyancy in the U.S. equity markets, which made public companies relatively expensive takeover targets in 2014.

Exhibit 7

The vast majority of companies that are sold in the U.S. are acquired by another U.S. company. Foreign buyers typically represent only about 96% of acquisitions (Exhibit 8).

Exhibit 8

In each of the past 10 years, U.S. corporations have been more active in terms of the number of cross-border acquisitions than divestitures (Exhibit 9).

Exhibit 9

As indicated in Exhibit 10, over the past 10 years, European acquisition targets have been a favoured hunting ground for U.S.-based acquirers, far surpassing the number of European buyers of U.S. companies. The U.S. is net sellers to Canadian companies. U.S. buyers are also active in other regions, such as Latin America (Exhibit 10)

Exhibit 10

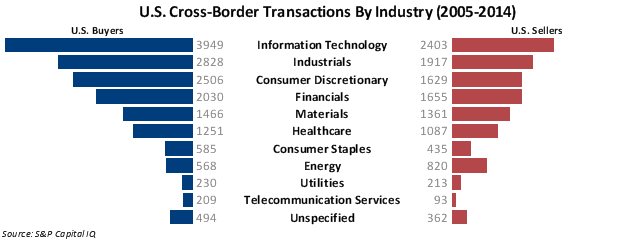

Over the past 10 years, U.S. companies are net buyers in virtually every industry segment, except for the energy sector (Exhibit 11).

Exhibit 11

A Canadian Perspective

The number of Canadian companies sold has been on the decline for the past several years. While 2014 saw the largest deal value (among reported transactions), transaction value remained relatively flat in U.S.-dollar equivalent (Exhibit 12).

Exhibit 12

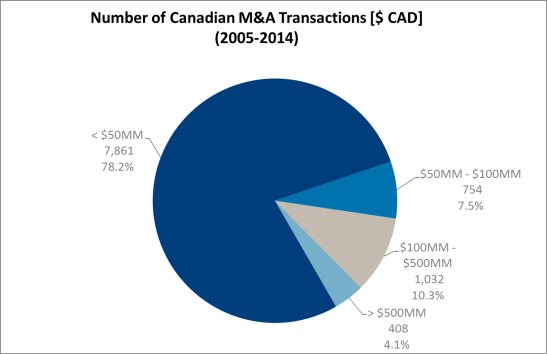

Compared to the U.S., Canada is much more a market of smaller companies. The median transaction value in Canada is approximately CDN$9.5 million. Furthermore, the transactions with a value of less than $50 million represented approximately 78% of all deals with reported values over the past 10 years, as contrasted with 71% in the U.S (Exhibit 13)

Exhibit 13

Approximately 14% of Canadian divestitures over the past 10 years represented a public company. This proportion is significantly greater than the level in the U.S. (less than 5%). The reason for this is that Canadian public companies are generally smaller than their U.S. counterparts, making the takeover of a Canadian public company more manageable. Furthermore, many Canadian public companies are “small-cap” and “micro-cap” entities, whose shares trade at relatively low valuation multiples due to their illiquidity. Consequently, they are relatively more affordable. The median takeover premium of Canadian public companies was approximately 30% in 2014 (Exhibit 14)

Exhibit 14

Over the past 10 years, approximately 75% of Canadian divestitures have involved a Canadian buyer (Exhibit 15). Canadian companies are most often the buyers for smaller companies, where it is not cost-efficient for a foreign buyer to undertake the time, effort and cost associated with a cross-border transaction.

Exhibit 15

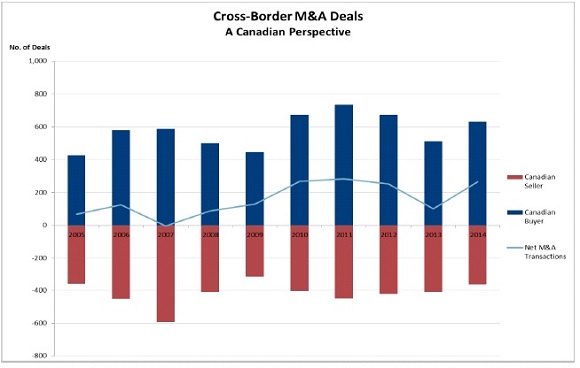

Despite much hype in the media about Canadian companies selling out to foreign buyers, the statistics reveal that Canadian companies have been more acquisitive abroad. In fact, Canadian buyers have been net acquirers in cross-border transactions in virtually every year since 2005 (Exhibit 16). This has been the case despite considerable fluctuation in the value of the Canadian Dollar against its US counterpart over that time period. This indicates that corporate acquirers generally are not influenced by short-term fluctuations in exchange rates when making long-term investment decisions.

Exhibit 16

Canadian buyers have been particularly acquisitive in the U.S., where over the 10-year period ending in 2014, Canadian companies acquired 3,349 U.S. entities, as contrasted with 2,845 Canadian companies being sold to U.S. entities (Exhibit 17). Relatively few transactions have been consummated between Canada, Europe and Asia. However, Canadian buyers have been active in other regions, such as South America, particularly in the materials sector.

Exhibit 17

On a sector basis, Canadian companies are particularly acquisitive in the materials sector. This is not surprising given the large resources companies located in Canada, whereas many of the resources are physically located throughout the world. The financial sector has also been a popular area for Canadian companies, particularly since the economic crisis in 2008. Canada’s large financial institutions have used their strong balance sheets to acquire significant assets abroad, particularly in the U.S.

Canadian companies are net sellers in the areas of information technology and industrials.

Exhibit 18

Cross Border Opportunities and Benefits

Cross-border transactions can offer buyers significant upside potential, assuming that things unfold as expected. Among the key drivers for consummating cross-border deals are the following:

- Revenue and Profit Growth. Many economies, including the U.S. and Canada have experienced low to moderate growth in recent years. Many corporations have saturated their home markets. A cross-border acquisition can result in significant revenue and profit growth without cannibalizing home-market operations. Even by acquiring a company in another low-growth jurisdictions such as Western Europe, the additional revenue from the acquisition can be significant. Companies operating in relatively low-growth markets are more likely to sell for reasonable valuation multiples, thereby facilitating the creation of shareholder value for the buyer.

- Diversification. One of the greatest benefits of a cross-border transaction is the added degree of diversification that it can bring to the buyer in terms of customer base, product/service offerings, management team and other key parameters. Diversification is associated with risk-reduction, which can lead to shareholder value creation.

- Economies of scale. Cross-border transactions can result in significant economies of scale that may include centralized administration, production, design engineering, management and other aspects of the buyers` operations. However, potential economies of scale must be weighed against the challenges of dealing with logistical issues, local preferences and other dynamics of varied markets.

- Access to lower-cost inputs. Many buyers have benefited from acquiring a company in a low-cost jurisdiction (such as parts of Asia). For product providers, the benefits of low-cost labour must be weighed against the added costs of foreign shipping and possible logistical and operational issues.

- Sharing of best practices. A benefit of cross-border transactions that is often under-estimated is the sharing of best practices between the buyer and the seller. While best practice sharing is applicable in any transaction, the benefits can be even more pronounced when dealing with foreign markets that may have vastly different ways of doing things. Again, cultural differences may impact the ability to implement different practices.

- Perception Value. Companies that operate in multiple jurisdictions are often viewed as being more valuable than their counterparts of a similar size due to the perception of market reach, diversification and growth potential. This can be particularly attractive for public companies and private equity firms looking to prepare their portfolio companies for sale.

Cross-border Risks and Challenges

While cross-border transactions offer upside potential, there are also significant risks and challenges that must be carefully considered. Some of the most notable are as follows:

- Cultural Differences. There are vast differences in culture around the world that buyers often fail to appreciate. These differences show themselves in many ways, including work ethic, decision-making, and communication protocol. Cultural incompatibility is frequently cited as the primary cause of a failed acquisition, as it results in employee demotivation and the loss of key employees.

- Language Barriers. Differences in language can hamper communication efforts between the buyer and employees of the acquired company. Differences in expectations and understanding result in errors, delays and aggravation for all parties. The buyer should secure communication channels with individuals at the acquired company who have a strong command of both the buyer’s language and the seller’s language (both verbal and written), and who can effectively convey messages in both directions.

- Integration. Attempting to fully integrate an acquired company in a foreign jurisdiction is fraught with challenges due to differences in culture, language, logistics and other reasons. However, abandoning integration efforts can result in a significant loss of synergies. Therefore, buyers must carefully consider potential integration issues and develop a comprehensive integration plan prior to consummating a transaction.

- Transfer Pricing. In many cases, the buyer and the acquired company will transact among themselves for the purchase and sale of goods and services. This may include the sale of raw materials and finished goods, as well as the provision of corporate services by the parent company (e.g. centralized treasury, general management, etc.) to the foreign subsidiary. The price charged for goods and services among related parties operating in different countries will likely be subject to scrutiny by local tax authorities. Transfer pricing has been a hot topic in recent years, as governments around the world become increasingly concerned about profits being shifted to other jurisdictions. Therefore, the buyer should commission a sound transfer pricing study from a credible third party provider, to avoid the added costs and management time of issues relating to non-compliance.

- Regulatory issues. Regulatory requirements are becoming increasingly stringent around the world, particularly those dealing with environmental, employment and safety concerns. The buyer must be well-apprised of local regulatory issues and potential changes therein before consummating a transaction. The buyer should also ensure that the target company has appropriate monitoring and control systems, and a strong record of regulatory compliance in order to avoid potential issues shortly after the closing of the transaction.

- Geo-political risks. Some parts of the world are exposed to significant geo-political risks that could include war, hyper-inflation, general strikes, political instability, the inability to repatriate funds and the expropriation of assets. The quantification of such risks can be very challenging due to the level of uncertainty involved. Therefore, buyers must carefully consider the consequences of acquiring a company that operates in an unstable environment. Not only is there the risk of a direct loss, but the buyer could be exposed to much broader reputational risk as well.

- Monitoring costs. The cost of monitoring and controlling the activities of a foreign subsidiary should not be underestimated. Financial and management reporting systems can be helpful, but they only report what has already transpired. Appropriate monitoring and control systems must be in place to proactively help ensure that operating performance does not significantly deviate from plan or that the target company is not subject to fraud or rogue decision-making.

- Foreign exchange risk. Cross-border transactions normally involve foreign exchange risk. This risk can be mitigated somewhat where the buyer finances the acquisition in the currency of the target company, or purchases goods or services in the currency of the target company. However in many cases the buyer remains subject to net foreign currency exposure, which must be carefully considered before consummating a transaction. The impact of negative foreign exchange fluctuations can be particularly harmful to public companies due to public equity market reactions to lower earnings.

Canada-US Cross-border Considerations

As discussed above, numerous M&A transactions take place each year between the U.S. and Canada. Despite having significant similarities, there are also important differences between the two countries in terms of market dynamics and regulations which must be considered prior to consummating a transaction. Witness the recent high-profile retreat of Target stores from Canada, which resulted in that company taking a loss in excess of $ 5 billion after just two years, when it failed to establish itself in the Canadian market.

- Valuation Multiples. As a general rule, Canadian companies tend to sell for lower multiples of EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization) than their U.S. counterparts operating in the same industry segment. This is partly because Canadian companies tend to be smaller than their U.S. counterparts. As such, they often do not attract the same number of large well-financed buyers, and many are more exposed to greater risk in terms of customer or market concentration. This can offer an advantage to U.S.-based firms looking to expand into Canada. In particular, U.S public companies whose shares trade at relatively higher multiples may get a lift on the Canadian earnings that they acquire for a lower multiple.

- Taxation. At the time of writing [2015], corporate income tax rates in Canada are lower than those in the U.S. The U.S. federal corporate tax rate is 35%. In addition, many states impose taxes on corporate profits, resulting in a total corporate tax rate of 40% or higher in some states. Conversely, the federal corporate tax rate in Canada is only 15%. Each province also imposes a tax on corporate profits, such that the overall rate generally ranges between 25% and 30% in most parts of Canada. While Canada imposes a type of value-added tax (i.e. the Goods and Services tax or a provincial Harmonized Sales Tax), there is no net cost to corporations. Canadian legislation also offers tax credits for qualifying R&D activities in Canada. However, U.S.-based firms looking to take advantage of the lower Canadian tax rate may find it challenging when they try to repatriate the additional profits back to the United States. While U.S. companies will either be structured as an S-Corporation (for privately held companies) or a C-Corporation, no such structures exist in Canada (where in effect Canadian companies are structured similar to C-Corporations and taxed at the corporate level, with a second layer of taxation at the shareholder level.

- Employment Benefits. While corporate tax rates are more favourable in Canada, personal income tax rates are significantly higher. This is partly because of Canada’s universal health care system. The advantage to employers in Canada is that they do not have to fund the significant cost of basic medical care as an employee benefit. Rather, most Canadian companies supplement universal health care privileges with added medical benefits (e.g. dental coverage, eye glasses and semi-private rooms) at a relatively low cost.

- Employment Laws. As a general statement, employment laws tend to be more favourable to employees in Canada than in the U.S. in terms of entitlement to severance pay, notice period maternity leave and other privileges. This can make it challenging for acquirers of Canadian companies to realize synergies through headcount reductions. By comparison, some states have “employment at will”, which means that terminations can be effected with little direct economic cost.

- Competition Law. There are a various tests for informing the Federal Trade Commission of a pending takeover transaction in the U.S. But in general, transactions with a value of less than US$76.3 million need not be reported. By contrast, the Canadian Competition Bureau requires disclosure where the acquired company revenues of CDN$86 million or more, regardless of value. Furthermore, the Canadian Competition Bureau will become involved with transactions in certain culturally-sensitive industries (such as publications), regardless of the transaction size. FTC or Competition Bureau involvement adds time, cost and complexity to a transaction. A buyer should ensure that their legal counsel is familiar with the pertinent legislation and how to make the experience as painless as possible.

- State and Provincial Regulations. Various states and provinces impose regulations ranging from how companies can conduct business, to product labelling and form filing. As a general statement, such requirements tend to be more onerous in the U.S. than in Canada, particularly for companies operating in multiple states. The exception in Canada is Québec, which imposes strict language requirements.

- Transaction Closing. Most transactions in Canada are effected by a “plan of arrangement”, which is a relatively simple court procedure. By contrast, U.S.-based transactions normally are conducted by way of a merger, which can be more costly and time consuming to effect.

- Deal Points. There are some differences in usual deal points in Canada vs. the U.S., such as those involving indemnity provisions and so-called baskets and caps (i.e. minimum and maximum amounts). These deal points tend to be more in favour of the buyer in Canada compared to the U.S.

Conclusions

M&A activity has been buoyant in recent years, particularly in the U.S. Cross-border transactions are becoming increasingly prominent, as corporate buyers seek incremental growth opportunities and diversification. However, the potential benefits of cross-border deals must be tempered with a critical assessment of the risks involved.