Before the American Invents Act, the U.S. had a "first-to-invent" patent system. That system included provisions for resolving disputes concerning who was the first to invent, called "interferences," and took place both before the USPTO and the courts (pre-AIA §135 and §291). Interferences between parties who collaborated or otherwise shared communications often involved issues of first-to-invent, i.e., priority and derivation. Priority and derivation are alternative theories, however, as one who derives an invention is neither a first nor a second inventor; he is a noninventor. Derivation has been a recognized issue in interferences, as well as a ground for invalidating a patent in court or rejecting a claim during prosecution (pre-AIA §102(f)).1

The AIA maintained the focus on the inventor as it transformed the U.S. patent system from "first-to-invent" to "first-inventor-to-file." Congress sought to preserve the requirement that the first to file a patent application actually invented the subject matter, rather than derived it from another. The U.S. patent statute requires that a patent application identify the true and original inventor or inventors.2 Even with the possibility under the AIA of an assignee filing an application, the inventor(s) must be named on the face of the U.S. patent application. Thus, "first-inventor-to-file" is a more precise phrase to describe the post-AIA U.S. patent system than "first-to-file."

Under the AIA, inventorship is central to determining compliance with §112(b), priority assertions, antedating references, eligibility for prior art exceptions, double patenting, eligibility for common ownership benefits, and derivation. In this article, we will take a close look at derivation. The AIA derivation proceeding recognizes the importance of a U.S. patent being awarded to a true inventor/innovator. An inventor may be the second to invent but the first to file, and will get a patent under the "first-inventor-to-file" system. But a party who does nothing but appropriate an invention from another is not entitled to a patent even if first to file.

The very first AIA derivation proceeding was instituted on March 21, 2018—more than five years after the AIA was enacted. Perhaps the most significant part of the AIA derivation proceeding is the ability of the USPTO to fashion remedies. The USPTO has the authority to change inventorship on any application or patent involved in the proceeding.3 The winner of the derivation contest could end up owning the losing party's application or patent if the Patent Trial and Appeal Board determines that the invention claimed in the application or patent represents the sole invention of the winning party. Once the correct inventor is named, the winning party may well be entitled to claim the benefit of the filing date of the losing party's application. And, as one can imagine, having such an earlier effective filing date can bolster patentability prospects. Remember, however, that the derivation proceeding is before the USPTO and the duty of disclosure fully applies.4 A victory may ring hollow if the patent obtained from a successful derivation proceeding is found unenforceable for inequitable conduct.

AIA Derivation Proceedings

AIA SEC. 3(n)(1) and (n)(2), found only in the AIA statute and not codified in 35 U.S.C. provide the effective date for AIA derivation proceedings. For any U.S. patent/applications with all claims having an effective filing date after March 15, 2013, AIA law will apply. For patents/applications with at least one claim having an effective filing date before March 16, 2013, and at least one claim having an effective filing date after March 15, 2013, AIA law applies, along with pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. §§102(g), 135 and 291.

The AIA amended both 35 U.S.C. §§ 135 and 291 relating to derivation proceedings for resolving inventorship disputes administratively and judicially. Under AIA 35 U.S.C. §135, a derivation petition must "set forth with particularity the basis for finding that an individual named in an earlier application as the inventor or a joint inventor derived such invention from an individual named in the petitioner's application as the inventor or a joint inventor and, without authorization, the earlier application claiming such invention was filed."5 The petition must be filed within one year of the earlier of the date on which the U.S. patent containing such claim was granted or the earlier U.S. application containing such a claim was published.6 If a derivation proceeding is instituted, the PTAB "shall determine whether an inventor named in the earlier application derived the claimed invention from an inventor named in the petitioner's application and, without authorization, the earlier application claiming such in vention was filed."7

The USPTO issued new rules to implement the AIA derivation proceedings.8 37 C.F.R. §42.405 sets out the threshold showing required. In particular, the petition must

- Demonstrate compliance with §§ 42.402 and 42.403; and

- Show that the petitioner has at least

one claim that is:

- The same or substantially the same as the respondent's claimed invention; and

- The same or substantially the same as the invention disclosed to the respondent.

37 C.F.R. §42.401 defines "same or substantially the same" as "patentably indistinct."

In addition, the petitioner must show "that a claimed invention was derived from an inventor named in the petitioner's application, and that the inventor from whom the invention was derived did not authorize the filing of the earliest application claiming such invention."9 Such a showing requires "at least one affidavit addressing communication of the derived invention and lack of authorization that, if unrebutted, would support a determination of derivation."10 The showing of communication must be corroborated.11 The PTAB decision on whether to institute a derivation proceeding is not appealable.12

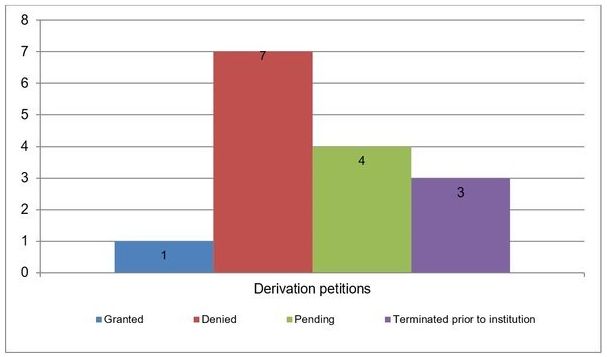

So far, there have not been many derivation petitions. According to the USPTO 2017 annual report, for the time period fiscal year 201 to fiscal year 2017, 30 derivation petitions were filed. The USPTO website at PTAB E2E lists 15 of these.13 Of the 15, one was granted, four are pending an institution decision, three were terminated prior to an institution decision, and seven were denied.14

First AIA Instituted Derivation Proceeding

The first instituted AIA derivation proceeding15 is Andersen Corp. v. GED Integrated Solutions Inc. (March 21, 2018).16 According to petitioner Andersen, one of its employees invented the device in question and showed it to GED officials in 2009. Then GED began selling the product and obtained a patent on it. In the petition, Anderson requested cancellation of GED's claims.

Andersen's application claims were identical GED's patent claims. Thus, the PTAB determined that Andersen's claims met the "same or substantially the same" standard relative to the GED patent claims. The PTAB analyzed the evidence of communication in the form of emails, a declaration, and work commendations. The PTAB noted that the "evidence reflects numerous interactions between Mr. Oquendo and employees of GED, including Mr. Briese, beginning on or around March 2009."17 The PTAB concluded that "Andersen has shown sufficiently that it ... has at least one claim that is the same or substantially the same as the invention disclosed to Mr. Briese and others at GED."18 Moreover, the PTAB determined that Andersen sufficiently showed that the filing of the application leading to GED's patent was not authorized by the Andersen inventor.19

Of note, Andersen asserted "that its inventor conceived of the subject matter of each of claims 1–22, and communicated each conception to GED. Thus, Andersen essentially has used its Petition to assert 22 different derivations covered by the pertinent rules (i.e., 22 different inventions that allegedly were derived)." The PTAB stated that it was "aware of no prohibition against this approach and thus treat the Petition accordingly."20 The PTAB specifically noted that it was appropriate under the rules for Andersen to assert 22 separate derivations in a single petition.21 The PTAB instituted the trial "on 22 allegedly 'conceived' and 'disclosed' inventions, as presented in the Petition." There is no procedural opportunity for the alleged deriver to respond prior to the institution decision.

Projections for the Future

It remains to be seen whether the PTAB's institution of the first post-AIA derivation proceeding means we will start to see more derivation proceedings. Looking at the filing numbers so far, it does not appear to be a proceeding many are pursuing. Perhaps parties consider it a better option to try and knock out an opposing party's claims via other routes. Perhaps parties are worried that they will be creating a record with too many risks for the future patentability of their own claims. Or perhaps it simply reflects uncertainty about the AIA derivation procedure and the PTAB standards for institution.

Those few petitions that have been filed and denied provide some examples of where petitioners are falling short. Remember, the derivation institution decision is not appealable, so there is no judicial review to tell us whether the PTAB is interpreting the law and rules correctly.

In Catapult Innovations Pty Ltd. v. adidas AG (July 18, 2014), the board denied institution, in part because petitioner did not identify how the disclosure matched the respondent's claim.22 In addition, the PTAB found the petitioner's evidence "presents argument and evidence of prior 'possession' and communication of the prior possession, instead of argument and evidence of prior 'conception' and communication of that prior conception."23 The PTAB noted that conception and communication of that conception is what a derivation claim requires.24

Other derivation petition denials, DER2016-00003 and DER2016-00021, were based on fatal deficiencies in their petitions, including, in each case, insufficient proof of conception of the claimed invention as a whole. DER2016-00002 was denied because the petitioner failed to meet the requirements that the petitioner's claim is the same or substantially the same as the disclosure to the respondent and the respondent's claim. And DER2016-00022 was denied because the petitioner did not satisfy Rule 405, set forth above.25

These denials highlight the continued importance of excellent record-keeping in post-AIA patent practice. Obtaining a patent in the USPTO can still depend on proof of a date of invention, even under the AIA first-inventor-to-file regime. Equally important is presenting a complete derivation petition meeting the requirements of the statutes, regulations, and case law. Failing to follow any part of Rule 405 or present evidence supporting conception and communication under the derivation case law may result in the denial of a derivation petition.

Footnotes

1 A person shall be entitled to a patent unless—(f) he did not himself invent the subject matter sought to be patented...

2 See, e.g., 35 U.S.C. §101 and §115.

3 See 35 U.S.C. §135(b).

4 37 C.F.R. §1.56.

5 35 U.S.C. §135(a)(1).

6 35 U.S.C. §135(a)(2).

7 35 U.S.C. §135(b).

8 37 C.F.R. PART 42 — TRIAL PRACTICE BEFORE THE PATENT TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD, Subpart E.

9 37 C.F.R. §42.405(b)(2).

10 37 C.F.R. §42.405(c).

11 Id.

12 37 C.F.R. §42.71(c).

13 On June 11, 2018.

14 DER2013-00001, DER2014-00002, DER2014-00005, DER2014-00006, DER2015-00003, DER2015-00005, DER2015-00009, DER2015-00011, DER2016-00001, DER2016-00002, DER2016-00003, DER2016-00021, DER2016-00022, DER2017-00007, DER2018-00008.

15 Interestingly, derivation recently arose in the context of a litigation. In Cumberland Pharm. Inc. v. Mylan Institutional LLC, 846 F.3d 1213 (Fed. Cir. 2017), Mylan asserted invalidity on, inter alia, "derivation of the claimed invention from someone at the FDA." However, the district court ruled that Mylan did not show anyone at FDA conceived of the claimed invention prior to the named inventor. The Federal Circuit affirmed, noting that the standard for conception in a derivation analysis is the same as for inventorship.

16 Andersen Corp. v. GED Integrated Solutions Inc., DER2017-00007, Paper 32 (P.T.A.B. March 21, 2018)

17 Id at 16.

18 Id. at 17.

19 Id. at 18.

20 Id. at 14.

21 Id. at 14.

22 Catapult Innovations Pty Ltd. v. adidas AG, DER2014-00002, Paper 19, at 18 (P.T.A.B. July 18, 2014). See also, Catapult Innovations Pty Ltd. v. adidas AG, DER2014-00005 and Catapult Innovations Pty Ltd. v. adidas AG, DER2014-00006.

23 Id. at 19

24 Id.

25 37 C.F.R. §42.405. There have been three derivation petition terminated prior to institution. In DER2015-00009, the parties settled prior to institution and the PTAB terminated the proceeding. In DER2015-00005, the petition was dismissed because both applications at issue were abandoned. In DER2015-00011, the petition was dismissed because the petitioner did not have a filed patent application.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.