Fund Manager and Investor Impacts of the ESVCLP Regime

The Early-Stage Venture Capital Limited Partnership (ESVCLP) regime was introduced in 2007 to stimulate the early-stage venture capital sector in Australia. The regime provides generous tax concessions to investors and fund managers alike. Under the regime, investors are typically exempt from tax on all or part of the returns they receive from eligible venture capital investments (EVCI) and are entitled to a non-refundable carry forward tax offset of up to 10 percent of the amount they invest. Likewise, fund managers benefit from deemed capital account treatment for their carried interest entitlements.

Whilst it is an attractive regime to both investors and fund managers, in practice, applying it has proven at times to be anything but straightforward. There are numerous quirks, some intentional and some not, that have caused issues for fund managers and investors at various points in the fund lifecycle. We have set out below a small selection of the issues that we have encountered when advising on the ESVCLP regime.

Transferring assets from an ESVCLP to a continuation fund

The ESVCLP regime prescribes that an ESVCLP must not remain in existence for more than 15 years. However, it is common for the fund constituent documents to specify an even shorter time frame, often 10 years, with short term extensions generally available upon receiving the necessary approvals.

As the initial wave of ESVCLPs near the end of their lifespans, many fund managers are now contemplating optimal strategies for winding down their funds. Funds that hold standout assets have increasingly been looking to transfer those assets into continuation funds so that the fund manager and investors can maintain exposure to them, rather than sell them off into a challenging market.

Transferring assets into a continuation fund brings about many challenges from a tax perspective. One of the biggest challenges tends to involve the crystallisation of the carry recipients' carried interest entitlements. This can be especially problematic where the carry recipients receive their entitlement in the form of an interest in the continuation fund, rather than a cash payment, as this may leave the carry recipients with a tax liability but no cash with which to fund it.

Fund managers should ensure that they proactively plan for this situation, to ensure that it is appropriately managed and carry recipients are not unexpectedly left with a large tax liability. Before establishing future funds, fund managers should also consider whether the fund can be structured from the outset in a way that allows carry recipients' carried interest entitlements to be "rolled" over to a continuation fund without triggering a tax liability.

When an ESVCLP portfolio company's assets exceed $250 million

Prior to 2016, ESVCLPs were required to sell their interest in a portfolio company once the value of the portfolio company's assets exceeded $250 million.

Whilst this restriction no longer applies — ESVCLPs are allowed to retain their interest in a portfolio company even after the value of the portfolio company's assets has exceeded $250 million — any gain that accrues after this threshold is crossed is potentially subject to tax.

In the past few years, a growing number of Australian startups have conducted large capital raises and gained "unicorn" status, pushing them into this bucket. And as most of the portfolio companies that fall into this category are held by ESVCLPs nearing the end of their lifespan, this is becoming an increasingly relevant issue for many funds.

The primary question that this raises relates to the tax treatment of gains that accrue after the $250 million asset threshold is crossed. If the gains are on capital account, domestic investors are potentially eligible for the capital gains tax (CGT) discount, and foreign investors are potentially eligible for a tax exemption. Conversely, if the gains are on revenue account, it may be the case that no concessions are available, potentially leaving investors subject to tax on the gains at their marginal tax rate.

Regrettably, the law does not deem these gains to be on capital account, in the same way that it does for gains made by a managed investment trust or complying superannuation fund. Instead, the fund manager is left to determine the characterisation of the gain, weighing longstanding (but often unclear) principles distinguishing between gains on capital and revenue account.

The fund manager is often required under the fund constituent documents to provide investors with sufficient information to complete their income tax returns. If a fund has disposed of a portfolio company whose assets had a value that exceeded $250 million, fund managers will need to consider whether the gain should be characterised as being on capital or revenue account, so that they can provide useful guidance to their investors, and ensure that the disclosures in the ESVCLP's income tax return are correct.

Follow-on investments in ESVCLP portfolio companies

An ESVCLP will typically invest in the early capital raising rounds of a portfolio company. As the portfolio company grows and raises further capital via additional funding rounds, the value of its assets may exceed $250 million, or it may cease to be an Australian resident for tax purposes.

Whilst the ESVCLP regime would usually permit an ESVCLP to make a follow-on investment in these circumstances, such follow-on investments do not typically qualify for the investor ESVCLP tax concessions. This exposes investors to a range of issues, including the need to determine the characterisation of the gains made on these investments.

Whilst this structure tends to be simple to administer, it usually provides investors with worse tax outcomes, including less certainty, than a "stapled" fund would. Whilst it can vary depending on the circumstances, a "stapled" fund would typically consist of an ESVCLP and a managed investment trust (MIT) that share the same pool of committed capital.

Fund managers who wish to have the flexibility to make follow-on investments using the same pool of committed capital should consider utilising a "stapled" fund structure for their future funds.

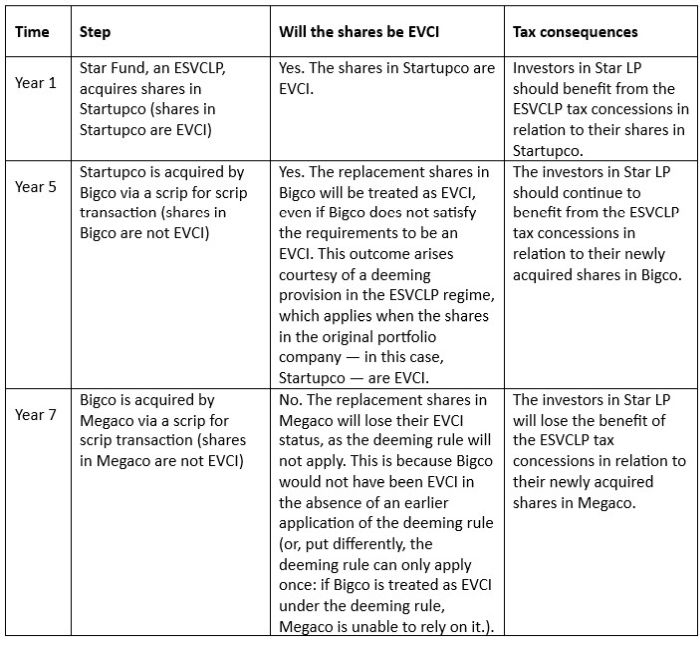

Scrip for scrip acquisition of ESVCLP portfolio companies

The 2023 IPO market grappled with economic headwinds, with a notable contraction in companies being taken public compared to previous years. As a result, startups have remained private for longer, leaving them more open to acquisition by larger and more established companies in their field. This can lead to a number of issues for ESVCLPs.

Consider the following scenario:

This scenario highlights just one of the many tax issues that can arise when a scrip for scrip transaction occurs. Every deal has its nuances and fund managers must carefully consider the tax implications that can arise upon entering into such transactions.

ESVCLP portfolio companies exiting through an asset sale

One of the many exit strategies available to the owners of portfolio companies is to sell the assets of the company, rather than its shares, and return the proceeds to investors in the form of dividends. This approach is often favoured by purchasers, as they can avoid inheriting the portfolio company's historical risks. However, this approach can lead to materially worse tax outcomes for ESVCLPs.

There are two main issues that tend to arise:

- The portfolio company will typically have to pay a minimum of 25 percent corporate tax on any gains. This will be taken out of the proceeds that are passed on to investors. Had the fund instead opted for a share sale, the gain may have been tax free for investors (that is, taxed at neither the investor, fund nor portfolio company level).

- If the portfolio company sells its assets, it may lose its status as an EVCI. This could result in the proceeds being taxable to investors upon receipt, without the benefit of the CGT discount.

Investors typically anticipate tax-free returns from an ESVCLP. When returns are taxable, it can lead to challenging discussions between fund managers and investors. ESVCLP managers should be very careful before agreeing to an asset sale, given the impact it may have upon their investors' after-tax returns. Given that deals of this nature tend to move quickly, it is usually best to flag this with portfolio companies upfront to avoid surprises later.

Investment syndicates

In the only court or tribunal case to date involving the ESVCLP regime, a decision by Innovation Australia to refuse ESVCLP registration to a fund was affirmed by the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) in Elcano Capital LP v Innovation Australia [2010] AATA 679.

Briefly, the key feature of the taxpayer's proposed model was for investors to participate in what was described as "a 'unitised' venture capital model." The proposed structure ensured that investors were not required to have exposure to all of the fund's investments. Instead, they could pick and choose which investments they would have exposure to.

In theory, what this structure would have allowed is for some business owners to hold their own business indirectly through the ESVCLP. As the interests were "unitised," each business owner, with the cooperation of the fund manager, could ensure that they only had exposure to their business and, just as importantly, that no other person had exposure to their business. In substance, it would have allowed business owners to retain complete control and ownership over their own businesses, whilst converting dividends and any profits upon sale to a tax-free form.

The AAT affirmed Innovation Australia's decision not to grant conditional registration to the partnership. The Tribunal said that the legislature intended that an ESVCLP have a spread of investors, usually a minimum of four, and a spread of investments, again, a minimum of four. The Tribunal said that the fund's model was "quite to the contrary. It would allow a single investor to invest in a single project." Its view was that the structure proposed by the fund was contrary to the legislative intent of the ESVCLP regime and would permit direct investment.

Whilst this case involved a particularly extreme example, it does highlight the caution that is needed when setting up a fund with an investment syndicate style structure, that is, a structure that gives investors the option to participate on a deal-by-deal basis.

The key lesson: Speak to your advisor

We have worked with a number of venture capital funds through their formation, investing, harvesting and windup phases, and have encountered and helped solve many of the issues that arise during each. In our experience, these issues are often easier to deal with the earlier they are confronted, as appropriate and thoughtful planning can go a long way to minimising (or eliminating) their impact. We at A&M would be pleased to speak to you, regardless of whether you are a fund manager or an investor, about the application of the ESVCLP regime or other matters pertaining to venture capital investments.

Originally Published 27 March 2024

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.