A recent decision by the Australian Patent Office demonstrates the risks of filing a patent application for an invention that one was not responsible for conceiving. The decision of Vuly Pty Ltd v Wei Yang [2020] APO 13, delivered on 28 February 2020, resulted in a patent applicant losing ownership of his patent applications to his ex-employer after it was found that he had learned of the concept behind the invention from two work emails that had been sent to him.

Background

The parties in the present dispute were Vuly Pty Ltd (Vuly), a company that designed and manufactured trampolines, and Wei Yang, a mechanical engineer and former employee of Vuly.

In July 2014, four months after the end of his employment at Vuly, Mr Yang filed a Chinese patent application for a trampoline with a distinctive support frame designed to provide improved structural integrity. He subsequently filed a PCT application and two Australian patent applications claiming priority from the Chinese application, all under his name.

In February 2017, Vuly filed its own Australian patent application for the same invention. Vuly's application claimed priority from Mr Yang's Chinese filing, which prompted the Australian Patent Office to challenge Vuly's right to the grant of a patent for the invention.

Vuly had always maintained that it, not Mr Yang, was entitled to the patent because Mr Yang had not actually devised the invention but had only learned of it after it had been disclosed to him by others in the course of his employment.

Vuly sought recognition of its rights to the invention by filing a request under section 36 of the Patents Act 1990, whereby a person is able to claim to be entitled to an existing patent application owned by another person (in this case, Mr Yang's patent applications).

Several such requests filed by Vuly in the past had been invariably unsuccessful due to a lack of sufficient evidence. On the contrary, the present request resolved to Vuly's benefit thanks to new evidence it was able to provide.

Eligibility for the grant of a patent

In general terms, a patent for an invention may be granted only to an inventor or to someone who derives title to the invention from the inventor (e.g. through an employment contract).

The Australian Patent Office normally determines who can legitimately apply for a patent by making the following enquiries, derived from various court decisions:

- Identify the "inventive concept" of the invention;

- Determine who was responsible for the inventive concept and the time of its conception as distinct from its mere verification and reduction into practice; and

- Determine how any contractual or fiduciary relationships give rise to proprietary rights in the invention.

What was the inventive concept?

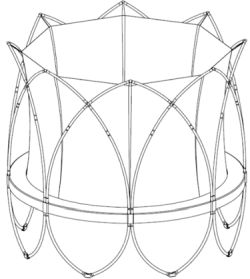

In order to identify the inventive concept at the heart of the invention, the Delegate of the Commissioner of Patents who heard the present case looked for the feature emphasised in Mr Yang's patent applications. He found this to be the frame of the trampoline, specifically the frame's support poles that joined after crossing one another at a location above the bounce mat of the trampoline, as shown in the figure below (taken from Mr Yang's Australian application no. 2017216515).

The invention also had other features developed by Mr Yang. However, the Delegate considered these additional features to relate to the practical implementation of the inventive concept as opposed to its conception, so that they did not form part of the inventive concept.

Who was responsible for the inventive concept?

The difficulty in establishing who was responsible for the inventive concept was a dearth of evidence. It was not apparent how Mr Yang had managed to acquire knowledge of the trampoline design during his time at Vuly given that Vuly had never produced a trampoline with such a design.

The critical evidence presented by Vuly for the first time in the present case comprised two emails sent to Mr Yang by Vuly's CEO on 26 April 2012 and 26 September 2013, during Mr Yang's employment. The emails included preliminary sketches of a trampoline which, like the one in Mr Yang's patent applications, had support poles that crossed over each other.

Mr Yang, for his part, essentially denied having any recollection of those emails, which was not implausible considering that the emails had not required him to take any action and it wasn't actually clear why they had been sent to Mr Yang in the first place.

Nevertheless, the Delegate was satisfied that, on the balance of probabilities, Mr Yang had been made aware of the inventive concept from the two emails and he wouldn't have been able to isolate that information in his mind, after acquiring it, in order to re-create the inventive concept himself without the information in those emails recurring to him.

Thus Vuly was found to be solely entitled to Mr Yang's patent applications.

Were there any contractual obligations?

Mr Yang's employment contract with Vuly had required him to assign all intellectual property created by him to Vuly. This, however, did not bear on the Delegate's decision because Mr Yang, not having been responsible for the inventive concept, had not actually created the intellectual property defined by his patent applications.

Take-home points

In order to determine who has the right of ownership to a patent, it is essential to first determine what the actual invention is, who is responsible for the invention, and what contractual obligations they may have. Failing to properly answer these questions exposes one to the risk, borne out by the present decision, of losing ownership of one's patent applications.

Originally published 14th April 2020

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.