The Melbourne Technology, Media & Commercial group consists of Andrew Chalet, Sarah Caraher, Kai-Li Tan, Sarah Dolan, Michelle Dowdle, Janice Luck, Shomit Azad, Tim Lyons.

Archaeologists working on the artefacts of Tutankhamen’s tomb recently discovered the world’s oldest white wine.

As you might expect after 3,000 years, the wine jars given to the pharaoh as gifts for the after life contained only residues. Interestingly, each of the wine jars were labelled with what appear to be a year, style, vineyard, place of origin and winemaker. A typical example read, ‘Year 5. Sweet wine of the Estate of Aton of the Western River. Chief vintner Nakht’.

The problem with this method of labelling wine is that the names we give to wines blur the lines between the name of the grape variety, the method of wine making and the geographical origin. Our natural inclination before brands were commonly used was to name products after their place of origin. For example, angora wool (Ankara, Turkey), manchester for bed sheets and similar products (Manchester, UK) and damask for fine weavings (Damascus, Syria). For the same reason that we don’t demand our manchester be made in Manchester, it was natural that we should call wine ‘champagne’ or ‘madeira’ if it was made using the methods of the Champagne region or of the Madeira Islands.

The impact of commercial pressure on this method of naming has, over the last ten or twenty years, led to controversy between the European Union and Australia, and between Australian winemakers seeking to delineate the boundaries of their own regions. The response of the Australian Government has been to regulate the system further, entering into a number of treaties with the European Union and setting up the geographical indicator register which lists those names that are protected within Australia.

The 1994 Wine Agreement

The terms used by Australian winemakers when describing wine cannot overlap with certain geographical protected terms. This prohibition arises from international treaties, primarily the 1994 Wine Agreement with the European Union, and a number of successive amending treaties. The Australian Government has ratified this treaty, converting it into Australian law. The protection of particular geographical terms is a gradual process, involving several stages of restriction. Some of these restrictions include:

- Certain words cannot be used at all by Australian winemakers unless the wine originated in those geographical indicators (for example, Beaujolais, Chianti and Madeira).

- Some words can only be used if the wines are not exported to the European Union (for example, Chablis and Moselle).

- Some words can only be used if the wine is not exported to Europe and the winemaking process adheres to certain strict criteria. For example, Champagne must be bottle-fermented in a bottle not exceeding five litre capacity and aged on its lees for not less than six months.

The Australian Government is currently negotiating a new agreement to replace the Wine Agreement. It is likely that more names will be protected under this agreement, due later this year.

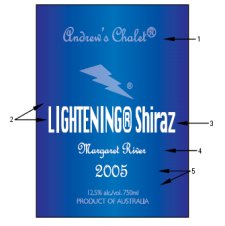

Anatomy Of A Wine Label

The typical wine label involves a number of legal issues beyond the question of compliance with the Wine Agreement and can give rise to issues of business names, trade marks (including geographical indicators), copyright and other regulatory requirements.

- The name of your business, which must be a registered business or company name. This requirement is designed for the consumer’s and the government’s benefit, not for yours. It ensures all businesses can be easily identified for regulatory purposes, but does not provide any rights to protect the name against infringers. To properly protect your company or business name, it needs to be a registered trade mark.

- A chosen graphic or brand name may need to be protected by registering it as a trade mark. The ® symbol next to the lightening graphic and the word LIGHTENING indicates both are registered trade marks. Distinctive logos, such as the lightening symbol, brand names, colours and even distinctive bottle shapes can and should be protected as registered trade marks. There may also be copyright in the logo or any images you use for your label. Therefore, in addition to registering your logo as a trade mark, make sure that you own the copyright in your logo or images, or - at the very least - have a license to use it on your wine label.

- The wine style or grape variety may be protected under the 1994 Wine Agreement system, discussed earlier.

- The geographical indication, which indicates compliance with the register of the protected geographical names. The boundaries of each zone, region and sub-region are determined by the Geographical Indications Committee of the Australian Wine and Brandy Corporation. Geographical indication may not be used in a misleading manner and only if the use meets criteria.

- Legislation requires that certain information be put on a label with minimum standards set. Due to these minimum standards, precisely what must appear on the label varies from wine to wine. Some constants are the requirement to list alcohol content, volume of standard drinks and country of origin.

Future Trends?

With the next wine agreement likely to further limit the names we can place on Australian wine, those in privileged geographical positions may try to further secure their precious origin. The protection of valued geographical regions is a trend that extends beyond the wine industry. For example, the Australian beef industry has long used the word ‘wagyu’ to describe beef from the Wagyu breed of cattle. The term ‘wa gyu’ literally means ‘Japanese cow’ or ‘Japanese beef’. Japan has asserted that only Wagyu cattle bred in Japan deserve the title and recently announced that it will reject any foreign beef labelled as ‘wagyu’.

However, there are those suggesting the trend may be moving in the opposite direction. Perrier, the mineral water brand owned by Swiss manufacturing giant Nestlé, traditionally denotes water from one particular spring in the south of France, called Perrier. Nestlé, facing labour disputes, has recently threatened to move production to another country, perhaps in eastern Europe or Asia. The French reject the idea, but Nestlé management suggest that the brand would be as powerful in any place.

Having a comprehensive understanding of industry trends and the international agreements under development will ensure that Australian winemakers not only avoid the storm before it hits, but are well placed in the market to develop and exploit their brands globally now and for many years to come.

Key Points

- The natural inclination to describe products by their place of origin gives rise to conflicts with those who wish to protect or limit the use of the name of their geographical area. There is a trend towards those who currently reside in an area to limit and tighten their control over the use of the name of the geographical area.

- Certain words and phrases cannot be used on wine labels under international agreements.

- You need to know about registered company and business names, trade marks and the regulatory requirements for labelling your wine.

Phillips Fox has changed its name to DLA Phillips Fox because the firm entered into an exclusive alliance with DLA Piper, one of the largest legal services organisations in the world. We will retain our offices in every major commercial centre in Australia and New Zealand, with no operational change to your relationship with the firm. DLA Phillips Fox can now take your business one step further − by connecting you to a global network of legal experience, talent and knowledge.

This publication is intended as a first point of reference and should not be relied on as a substitute for professional advice. Specialist legal advice should always be sought in relation to any particular circumstances and no liability will be accepted for any losses incurred by those relying solely on this publication.