Introduction

More than two‐thirds of Ontario companies charged under the Occupational Health and Safety Act plead guilty. Defendants who plead guilty and allow the court to set their fines pay, on average, 40% less in fines than defendants who plead guilty and accept the Ministry of Labour's proposed fine. At least one party is convicted and fined in 82% of Ontario workplace incidents that result in occupational health and safety charges. Two‐thirds of corporations that go to trial are found guilty. These are some of the nine findings that we have drawn from our study of unpublished prosecution data obtained from the Ontario Ministry of Labour through a Freedom of Information request.

From the data, which involves 863 defendants - 592 corporations and 271 individuals such as supervisors and workers - charged with offences under the Occupational Health and Safety Act, we have been able to paint a statistical picture of what actually happens when employers, supervisors, workers and others are charged under the Occupational Health and Safety Act. All of the charges in our study were resolved during the eighteen-month period from January 2009 to June 2010.

Our nine findings from the data are set out in this report.

Summary: Results of Occupational Health and Safety Act Charges against 863 Defendants The following summarizes the results of the charges against the 863 defendants.

Figure 1. Results of Occupational Health and Safety Act Charges (Combined for Corporations and Individuals)

The Unpublished Ministry of Labour Data We Analyzed

Our study focuses on the Occupational Health and Safety Act's charging provisions, which permit the Ministry of Labour to charge employers, supervisors, workers and others with offences under the Act, and prosecute them through the courts. Defendants found guilty of Occupational Health and Safety Act charges can incur significant fines: up to $25,000 per charge for individuals and up to $500,000 per charge for corporations.

As noted above, to obtain the necessary data, we submitted a Freedom of Information request to the Ontario Ministry of Labour requesting data on prosecutions under the Occupational Health and Safety Act that were resolved during the period from January 2009 through June 2010. In response, we received internal Ministry of Labour reports that are unpublished. The Ministry of Labour creates these reports for "Part III" Occupational Health and Safety Act prosecutions and we received the reports for all prosecutions that were resolved during that eighteen‐month period. Part III charges are the more serious charges and do not include charges laid by way of a "ticket."

We entered the data from the Ministry of Labour reports into an extensive spreadsheet and then categorized cases by the type of defendant (corporations or individuals), the result (including whether the defendant pleaded guilty or fought the charges through to a trial), the severity of the worker's injury, if any, and the amount of the fine that was imposed. The data can also be analyzed by court location and other factors.

A Note on Our Terminology in this Report

We used the following six categories to characterize how the charges were resolved:

- Pleaded guilty and negotiated fine with Ministry of Labour: instead of going to trial, the defendant pleaded guilty to one or more charges, negotiated the fine with the Ministry of Labour, and accepted the fine that the Ministry of Labour proposed (also called "joint submission on sentence")

- Pleaded guilty and let the court decide the amount of fine: instead of going to trial, the defendant pleaded guilty to one or more charges and let the court decide the amount of the fine (that is, did not accept the fine that the Ministry of Labour proposed)

- Convicted after trial: the defendant fought the charges at trial and was found guilty on one or more charges (even if the defendant was found not guilty on other charges)

- Acquitted after trial: the defendant fought the charges at trial and was found not guilty on all charges

- Charges withdrawn – other party convicted: the Ministry of Labour withdrew the charges against the defendant, but another party pleaded guilty or was convicted after trial in the same incident (for example, charges against a supervisor were withdrawn, but the supervisor's employer pleaded guilty regarding the same incident)

- Charges withdrawn – no other party convicted: the Ministry of Labour withdrew the charges against the defendant, but from the data, it appears that no other party pleaded guilty or was convicted after trial regarding the incident that led to charges

- Charges stayed: the court put an end to the prosecution for reasons such as delay

Also, we use the word "conviction", on its own, to mean a finding of guilty, whether by way of a guilty plea (in which the defendant pleads guilty and the court then "convicts" the defendant) or by way of a finding of guilty after a trial.

We now set out the nine findings that we drew from the data.

Finding Number 1: Most Corporations Plead Guilty; Most Supervisor / Worker Charges Withdrawn

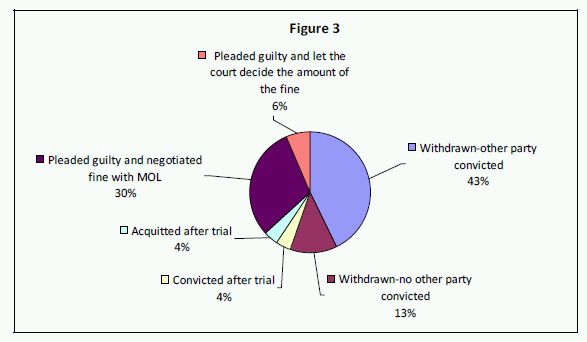

As the charts below show, 68% of corporations pleaded guilty to one or more charges and 26% of corporations had all charges against them withdrawn.

By contrast, only 36% of supervisors and workers pleaded guilty, while 56% of supervisors and workers had all charges against them withdrawn.

Of the 26% of cases where all charges against a corporation were withdrawn, approximately two-thirds of those cases involved another party – such as a related company - being found guilty of Occupational Health and Safety Act charges and fined in respect of the same incident. "Pure" withdrawals against corporations, where no other party was found guilty in relation to the same accident or incident, represented only 9% of all cases and 35% of cases where all charges were withdrawn.

Of the 56% of cases where all charges against an individual, such as a supervisor or worker, were withdrawn, more than three quarters of those cases involved another party, such as the employer of the individual charged, either pleading guilty or being convicted of Occupational Health and Safety Act charges after a trial. Less than one quarter of withdrawals against individuals – representing approximately 13% of all prosecutions against individuals - were pure withdrawals of the entire case.

Figure 2. Corporations: Results of Occupational Health and Safety Act Charges

Figure 3. Supervisors and Workers: Results of Occupational Health and Safety Act Charges

Finding No. 2: Two‐thirds of Corporations That Go to Trial Lose

As Figure 2 shows, only 6% of corporations fought their charges all the way through to a trial. Of those, two‐thirds were found guilty of at least one charge, and one‐third were found not‐guilty of all charges. Thus, statistically, the odds of success are reasonable, but not great for corporations that go all the way to trial. Individual defendants, such as supervisors and workers, tended to do better when they went to trial.

Only 8% of individual defendants fought their charges through to a trial, and of those, half won and half lost.

Finding No. 3: 82% of Incidents/Accidents That Result in Charges Produce at Least one Conviction

Our analysis of the data shows that if an accident or incident resulted in charges under the Occupational Health and Safety Act, there was an 82% probability that at least one person or corporation would be convicted and fined in relation to that incident.

Workplace accidents often result in charges against more than one corporation or individual. Take, for example, an accident at a construction site that results in charges against the general contractor ("constructor"), subcontractors, supervisors, and workers; the data shows an 82% chance that at least one of those parties would be convicted and fined. Only 14% of incidents that lead to charges – about 1 in 7 – resulted in all of the defendants avoiding convictions and fines.

Finding No 4: 85% of Charges Involved Actual or Potential Worker Injuries

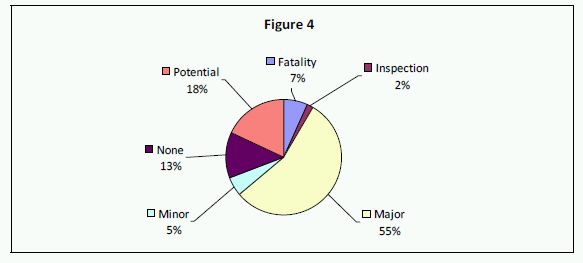

Only 15% of all charges laid against defendants arose from incidents in which there was no actual or potential injury to workers. A full 85% of charges resulted from incidents that produced injuries or potential injuries to workers. More specifically, 67% of cases involved actual injuries, and 18% involved a serious potential for injury if the safety hazard were not remedied.

Sixty percent of the charges involved a major injury or death, while only 5% of charges arose from minor injuries. These numbers are consistent with the commonly-held belief that the Ministry of Labour is far more likely to lay charges if an employee has been seriously injured. In categorizing injuries, we in general used the terms, such as "major" or "minor", that were used in the Ministry of Labour reports.

Figure 4. Prosecutions by Severity of Injury

Finding No. 5: Construction Industry Produces 1/3 of Prosecutions

The Ministry of Labour data showed that approximately 1/3 of all defendants charged under the Occupational Health and Safety Act were in the construction industry, which is notable given that, according to Statistics Canada, 5.2% of the Canadian economy is related to construction activities. Source: http://www.fin.gov.on.ca/en/economy/ecaccts /

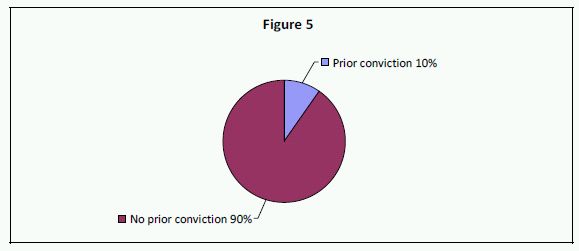

Finding No. 6: 90% of Defendants Had No Prior Safety Convictions

In 90% of the cases where defendants were charged, the defendants had no prior convictions under the Occupational Health and Safety Act. That is to say, only 10% of defendants had a prior conviction under the Act.

Figure 5. Percentage of Defendants with Prior Convictions under Occupational Health and Safety Act

Finding No. 7: Courts Tend to Set Lower Fines Than the Ministry of Labour Will Negotiate

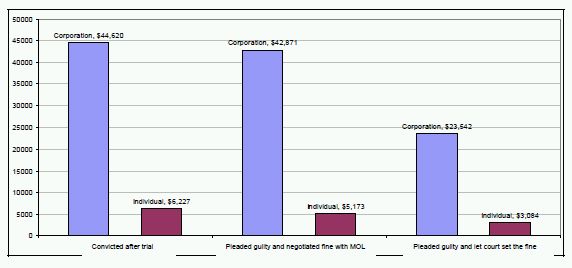

As mentioned above, 62% of corporations charged under the Occupational Health and Safety Act pleaded guilty and agreed to the fine proposed by the Ontario Ministry of Labour. Only 6% of corporate defendants pleaded guilty and asked the court to decide the amount of the fine.

We were very interested to see that corporate defendants who pleaded guilty, but rejected the Ministry of Labour's proposed fine and let the court decide the amount of the fine, tended to pay lower fines than those who settled the fine with the Ministry of Labour. The average fine for corporations that pleaded guilty and accepted the Ministry of Labour's proposed fine was $42,871, compared with $23,542 for corporations that pleaded guilty and asked the court to decide the amount of the fine. That is, fines decided by the courts for corporations were 45% lower, on average, than the fines that were negotiated by corporations with the Ministry of Labour – an illuminating statistic.

Similar results were found for individual defendants, such as supervisors and corporations. The average fine for individuals who accepted the Ministry of Labour's proposed fine was $5,173 compared with $3,004 for individuals who pleaded guilty and asked the court to decide the amount of the fine. That is, court‐decided fines against individuals were 42% lower than fines that individuals were negotiated with the Ministry of Labour.

We should note that even where the defendant and Ministry of Labour agree on a fine, and thus present a "joint submission" regarding the fine to the court, the court is not required to accept that fine. However, courts almost always approve the fine negotiated by the defendant and the Ministry of Labour.

How might we explain the difference between fines agreed‐upon with the Ministry of Labour and fines decided by courts in guilty pleas? One wonders whether many judges and justices of the peace, who decide the amount of the fines, think that the Ministry of Labour's proposed fines are simply too high. The data suggest that cases in which defendants asked the court to decide the amount of the fines tended to, on average, involve relatively less‐serious injuries, but that difference does not appear to fully explain the significant 40+% discount when the court actually decides the fine.

Individual defendants who pleaded guilty tended to be more comfortable with letting the court set the fine. Only 9% of corporations that pleaded guilty let the court set the fine, compared with 17% of individuals who pleaded guilty. The reason for the difference may be that individuals are more likely than corporations to expect sympathy from a court, given their lesser means and the personal impact of a conviction on them, and are therefore more prepared to give up the relative certainty of a negotiated fine and "take the risk" of letting the court determine the amount of the fine.

Overall, it appears to us from the data that corporations, supervisors, and workers may be too risk‐averse in resolving occupational health and safety charges; that is, defendants tend to agree to fines that are higher than most courts would impose if asked to decide the amount of the fine. Corporations, supervisors, workers, and their occupational health and safety defence lawyers, may wish to think more carefully about whether to ask the court to decide the amount of the fine, instead of agreeing to the fine demanded by the Ministry of Labour prosecutor.

Figure 6. Average Fines by Result of Charges

Finding No. 8: Ministry of Labour Tends to Give No Discount for Pleading Guilty

Many defendants in Occupational Health and Safety Act charges assume that if they plead guilty and negotiate the fine with the Ministry of Labour, they will incur lower fines than if they go to trial and lose. This perception appears, at least in respect of corporations, to be incorrect.

Fines for corporations who fight charges all the way through a trial tend to be roughly the same as fines negotiated with the Ministry of Labour on a guilty plea. This is another interesting result from the data.

The average fine against corporations that fought the charges through a trial and were convicted was $44,620, versus $42,871 against corporations that pleaded guilty and negotiated the fine with the Ministry of Labour ‐ a difference of only 4%.

Moreover, the severity of injury in the trial cases against corporations was actually greater, on average, than the severity of injury in the guilty pleas negotiated with the Ministry of Labour: 87% of cases that resulted in convictions after a trial involved fatalities or serious injuries, compared with only 77% of guilty plea cases. Because more serious injuries tend to produce higher fines, it would therefore appear that fines imposed by courts against corporations after a trial are, on average, roughly the same as fines negotiated with the Ministry of Labour – a telling result indeed.

In summary, the commonly‐held assumption that defendants facing Occupational Health and Safety Act charges can get a substantially lower fine by pleading guilty and accepting the fine proposed by the Ministry of Labour, is not supported by the data. Considering that one‐third of defendants who fight charges at trial are found not guilty of all charges, and fines after a trial are roughly the same as fines negotiated with the Ministry of Labour, corporations with arguable defences may wish to take a harder look at whether they should go to trial. Statistically, the data suggests that they stand a 33% chance of winning. Of course, there is the obvious cost of the legal fees associated with proceeding to trial, but the point is that a more complete cost‐benefit analysis should likely be conducted by defendants ‐ one that considers all possible courses of action.

Finding No. 9: Fines are Higher for More Serious Injuries

We expected the data to show that fines in cases of fatalities and serious injuries are higher than fines in cases with minor injuries. We were right.

The highest fines, by far, were in cases involving fatalities, followed by cases involving major injuries, minor injuries, potential injuries, and no injury ‐ in that order.

General Reflections on the Data and the Results

Despite the large number of charges under the Occupational Health and Safety Act, very few cases are actually decided by the courts. Only 6% of cases against corporations and 4% of cases against supervisors and workers go all the way to trial, meaning that only a very small percentage of cases require courts to fully analyze the case and produce helpful precedents.

Of the cases that go to trial, very few decisions are reported publicly in case law databases such as CanLII, Quicklaw or Westlaw. This leaves a very small body of caselaw that companies, supervisors and workers can draw upon to achieve a fair result in court. In the absence of caselaw, the prosecution reports that we obtained through the Freedom of Information request, fmc‐law.com 10 which contain a summary of each resolved case and are maintained in our database, are useful precedents as we defend our clients against occupational health and safety charges.

One could argue that the high proportion of negotiated fines produces, in a sense, a selfperpetuating body of fine precedents ‐ brief summaries of those cases, but not actual court decisions, are reproduced in a commonly‐used text ‐ that are used against defendants in subsequent cases. The unpublished data that we analyzed shows that fines that are actually decided by the court – not negotiated with the Ministry of Labour ‐ in guilty‐plea cases tend to be much lower than those negotiated with the Ministry of Labour.

In a similar vein, the Ministry of Labour tends to give effectively no "discount" to companies for pleading guilty and avoiding a trial; fines imposed by the courts after a corporation has fought all the way through a trial tend to be only 4% higher than fines negotiated with the Ministry of Labour. But, correcting for the fact that trial cases tend to involve more serious injuries, we can conclude that trial fines are roughly equal to negotiated fines.

As mentioned above, the data suggests that more corporations, supervisors and workers facing occupational health and safety charges should consider letting the court decide the amount of the fine, or in appropriate cases, the entire case. The data does not show any "discount" for pleading guilty and negotiating the fine with the Ministry of Labour.

About Fraser Milner Casgrain LLP (FMC)

FMC is one of Canada's leading business and litigation law firms with more than 500 lawyers in six full-service offices located in the country's key business centres. We focus on providing outstanding service and value to our clients, and we strive to excel as a workplace of choice for our people. Regardless of where you choose to do business in Canada, our strong team of professionals possess knowledge and expertise on regional, national and cross-border matters. FMC's well-earned reputation for consistently delivering the highest quality legal services and counsel to our clients is complemented by an ongoing commitment to diversity and inclusion to broaden our insight and perspective on our clients' needs. Visit: www.fmc-law.com

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.