The Global Competitiveness Report, 2012- 2013, published by the World Economic Forum is one of the most reliable sources of global competitiveness standards in 144 economies. The authors provide extensive qualitative and quantitative research in relation to each of the world's economies and they naturally include Cyprus in their study. A comparison of Cyprus, Malta and Luxembourg, as three innovation-driven economies of similar market size, demonstrates serious weaknesses in our national infrastructure and identifies problematic factors for doing business in Cyprus.

The Global Competitiveness Report identifies 12 pillars upon which competitiveness is based, each with its own sub-categories. The main 12 pillars are institutions, infrastructure, macroeconomic environment, health and primary education, higher education and training, goods market efficiency, labour market efficiency, financial market development, technological readiness, market size, business sophistication and, finally, innovation. At the top of the competitiveness ladder comes Switzerland, having maintained first place for three consecutive years. Singapore is in second place with Finland Sweden, the Netherlands, Germany, the US, the UK, Hong Kong SAR and Japan completing the ten most competitive economies in the world today.

The findings of the Report demonstrate that there is no necessary trade-off between being competitive and being sustainable. In fact, countries such as Switzerland which are top for competitiveness are also the best performers in many areas of sustainability. Such a conclusion comes to confront the entire austerity vs. growth dilemma in view of the ongoing euro crisis. The Global Competitiveness Report demonstrates that a combination of the two is the only way to increase productivity and combat unemployment. Cyprus has earned a Global Competitive Index score of 4.32, and ranks 58th out of 144 economies. Cyprus's previous ranking (2011-2012) was 47th out of 142 economies.

The euro crisis can explain this drop to a certain extent, since it reflects the lack of confidence on the part of the financial markets in the ability of the Southern European economies to balance their public accounts by curbing public spending and escaping the vicious circle of public debt. The lack of competitiveness in economies of Southern Europe, including Cyprus, coupled with high salaries, has led to unsustainable balances difficult to overturn unless measures are taken both to stimulate growth and to minimise public expenditure.

Cyprus, Malta and Luxembourg: A Comparative Analysis

While the 12 pillars of competitiveness affect all economies, they do so in different ways. For example, the best way for Kenya to improve its competitiveness is not the best way for Italy to do so. The reason behind this differentiation is that the two countries are at different stages of development. Speare also competitors with Cyprus in terms of jurisdictional attractiveness and in securing foreign investment. Analysing the findings of the Global Competitiveness Report can, therefore, provide useful insights into those areas which require restructuring and improvement.

Overall, the Global Competitiveness Index demonstrates that Luxembourg is well ahead in all categories when compared to Cyprus and Malta. The last two compete equally in most categories, with Malta doing slight better in most.

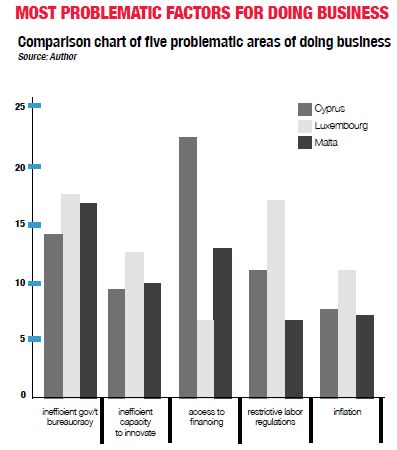

The table (left) depicts five areas which have been identified as problematic for doing business. The importance of this information is that these factors have been outlined by the Index's Executive Opinion Survey, which is carried out at the local level in the form of questionnaires addressed to the business community. The data gathered provides a unique source of insight into each nation's economic and business environment.

The most significant gap among the three countries is in access to finance, with Cypriot respondents considering difficulties in securing funds as one of the most serious and problematic factors for growth, posing obstacles in the promotion of business. Interestingly, the results of the Executive Opinion Survey show that respondents do not think Cyprus has insufficient capacity to innovate while the findings of the Report demonstrate the opposite.

Lows and Highs

In comparison to its Maltese and Luxembourg counterparts, Cyprus seems be at a stalemate when it comes to development of its financial market. Ranking 38th out of all 144 economies assessed by the index, Cyprus might appear to be doing rather well when it comes to the development of its financial market but not when directly compared to Malta, which achieves an impressive 15th place and Luxembourg (12th). The same can be noted when examining the technological readiness factor, where Cyprus is ranked 37th, left behind by Malta in 21st place and Luxembourg in an impressive 2nd.

The lower ranking of Cyprus (58th as opposed to 47th place last year) is the result of a number of factors, one of which is the lack of institutional efficiency. Cyprus ranks very low in the efficacy of corporate boards (a disappointing 139th place). Malta in 84th place and Luxembourg (16th) do much better in this aspect. Institutional delay and the lack of public-private collaboration can also be demonstrated when examining government services for improved business performance where Cyprus ranks 82nd but Malta is 39th and Luxembourg is well ahead of both, in 16th place. The same pattern is noted when examining favouritism in decisions by governmental officials and wastefulness in government spending. It appears that providing more vigorous cooperation between the public and private sphere with less public spending is an ongoing challenge for Cyprus. It must be said, nevertheless, that direct cross-country comparisons in terms of institutional efficiency and measuring public spending output is a complex procedure.

The coverage and scope of public services differ across countries, reflecting societal and financial priorities. These disparities require that public spending effectiveness be assessed by spending area, at least for the key components, including health care, education and social assistance.

In other important institutional areas such as the protection of minority shareholders' interests, Cyprus ranks 21st, depicting its sound services system. Equally important, Cyprus is attributed with a highly efficient legal framework in challenging regulations (18th place). Luxembourg also ranks high in this aspect (8th) while Malta lags behind in a low 68th place. Equally importantly, Cyprus achieves a good place in most higher education and training sub-pillars, namely the quality of its management schools and the quality of its educational system.

The same applies for goods market efficiency where Cyprus is in the top fifty countries in most categories. It is ranked 19th in total tax rates, 16th on the extent and effect of taxation and 6th on trade tariffs. The same motif can be seen in the use of the Internet and financial market development, where Cyprus ranks 11th on the legal rights index and 35th on the availability of financial services. Luxembourg performs better throughout, while Malta is on an equal standing.

A Problem of Innovation?

In most categories (institutions, infrastructure, macroeconomic environment higher education and training, etc.) Cyprus has an inconsistent performance of high and low points. The only category in which Cyprus has a consistently low ranking throughout and performs poorly is innovation. Malta does slightly better but still faces considerable problems while Luxembourg is well ahead, with heavy investment in R&D spending and good university-industry collaboration in R&D. The only sector in which Cyprus does well in terms of innovation is PCT patent applications, a success owed largely to service providers able to efficiently accommodate clients. Notably, Cyprus is ranked 52nd for the availability of scientists and engineers for R&D, which is something of an oxymoron: while the human resource expertise is present, it remains largely unexploited.

Innovation Promotion and Management: The Key to Growth and Development

Cyprus lacks a consistent innovation policy. Its semi-government institutions, limited by resources as most organisations nowadays, are not able to meet the challenge of innovation promotion. It appears that in the majority of cases, we are followers and not leaders in innovation policy. Local R&D is due to the vigorous attempts of universities and private entities to participate in EU funding programmes and to private companies exploring new products and services. Internal innovation is nonetheless very limited. Only a handful of enterprises actually invest in innovation and research, with most considering these as "soft issues" not to be dealt with in times of hardship.

Innovation Union, a new initiative promoted by the EU, particularly stresses the need for a genuine single European market for innovation which would attract innovative companies and businesses. To achieve this, several measures are proposed in the fields of patent protection, standardization, public procurement and smart regulation.

Innovation Union also aims to stimulate private sector investment and proposes, among other things, to increase European venture capital investments which are currently a quarter of those in the US. Moreover, throughout the Global Competitiveness Index it is evident that the countries which lag behind in innovation, lag behind generally. While small market size or less advanced institutionalisation may not seriously affect overall performance, a bad performance in innovation is a catalyst for unemployment, lack of private investment and less jurisdictional attractiveness. Investors are no longer interested in simply using a country for tax benefits; they want to fully exploit the potential of a jurisdiction in terms of human resources, production and services. Sustainable innovation cannot be achieved by one-size-fits-all and one-sided approaches. It requires a common understanding of what innovation is, and how it can be customised to suit needs at an entrepreneurial, national and regional level.

The Innovation Union Scoreboard 2011, a report measuring innovation among EU states, concludes that the countries at the top of the rankings share a number of strengths in their national research and innovation systems with a key role for business activity and public-private collaboration. While there is not one single way to reach top innovation performance, it is clear that the innovation leaders (Finland, Sweden, Denmark and Germany) perform very well in Business R&D expenditure. This shows that, when discussing innovation and R&D, we do not need to associate them with concepts such as heavy industry or industrial research. Innovation and R&D can take place not only in the production sector but also in the services sector; a law firm or a fiduciary service provider can easily become part of innovation initiatives through concrete planning and the introduction of new products and/or services. Hopefully, Cyprus will not drop further in next year's index but even if it does, it is worth considering the words of Michelangelo: "The greatest danger for most of us is not that our aim is too high and we miss it, but that it is too low and we reach it."

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.