As world leaders gather from January 15-19, 2024 to address emerging issues at the World Economic Forum in Davos under the theme of "Rebuilding trust", we analyse how the employment market has twisted and changed over the past few decades.

Over the last two decades, a number of shocks and crises have left their mark on the global economy and, in particular, the employment market. The 2008 financial crisis caused an economic contraction in almost all advanced economies, something we hadn't seen since the Second World War. Recently, the Covid-19 pandemic brought activity in many sectors to a full stop.

Recession and unemployment - two forces spinning in a duet

Recession and employment downturns go hand in hand. During such times, production levels drop, forcing companies to temporarily reduce their workforce so as to cut costs. While the unemployment rate during the shocks is also correlated with other various factors, including monetary and fiscal policies, the connection to production is clear and statistically supported. For example, in 2009, the International Labour Organization explained that global unemployment had peaked following the 2008 financial crisis.

The link between the economic turbulence and the unemployment rate is explained also by Okun's Law. This theory has it that the relationship between economic slowdown and job loss works out as follows: a 1% decline in the employment rate corresponds to a 2% to 3% decline in output.

Interestingly, in the short-term, economic recovery doesn't always lead to an immediate return to prior employment rates. This is partly because companies emerging from a recession tend not to be in a rush to hire new employees. Initially, they focus on restoring previous output levels using their existing workforce.

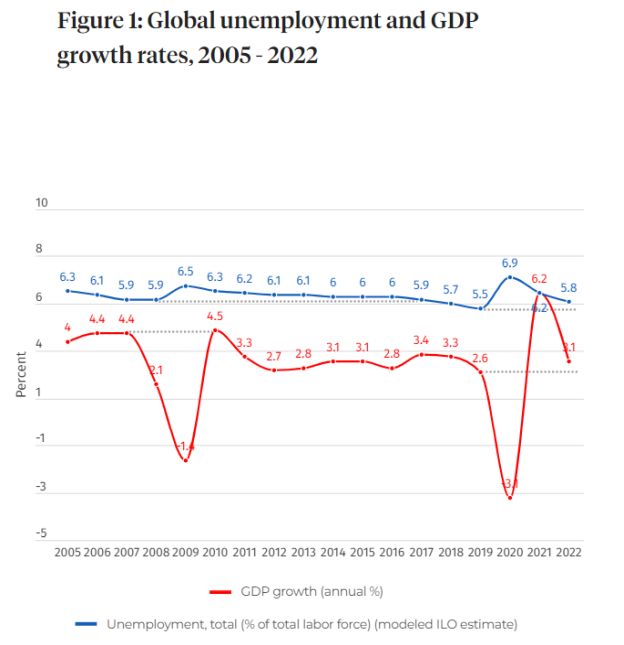

If we look at the unemployment rate (% of the total labour force, modelled on ILO estimates), in the post-2005 period, one of the highest peaks was 6.5% in 2009. However, in 2020, due to pandemic-related restrictions, the unemployment rate rose even further reaching 6.9%, compared to 5.5% in 2019. In the post-pandemic period, unemployment gradually declined to 5.8% in 2022.

On the other hand, annual percentage GDP growth in 2009 dropped to -1.4% compared to 4.4% and 2.1% in 2007 and 2008, respectively. At the start of the pandemic in 2020, economic growth plummeted further to -3.1%, compared to the pre-pandemic 2.6% in 2019.

As stated however, in the short-term, economic recovery doesn't immediately translate to a reduction in unemployment. While economic growth surged to 4.5% in 2009, it took eight years for the unemployment rate to return to the pre-crisis level of 5.9%. As shown in figure 1 below, a similar pattern was observed in the post-pandemic period too.

However, it is worth mentioning that the global growth rate never returned to pre-financial crisis levels over a 10-year average (mid-term). From 1998 to 2007, the GDP annual growth rate was 3.57%, while from 2009 to 2018, it averaged only 2.76%. In contrast, the unemployment rate for the same period before the 2008 crisis was 6.22%, and after the crisis, from 2009 to 2018, it decreased to 6.08% on average.

In general, whether the employment rate will rebound following a crisis and how swiftly the recovery will occur partially depends on the policies adopted at both the macroeconomic and microeconomic levels. For example, fiscal policies implemented during or after a crisis may stimulate hiring by offering support to companies to enhance their production. Similarly, on a company level, recovery from shock depends on the policies it adopts to facilitate its rebound.

Figure 1: Global unemployment and GDP growth rates, 2005 - 2022

Source: The World Bank Open Database

Wages and productivity growth: the broken link

Labour productivity growth and wage growth are two interconnected trends that often rise together. In a broad sense, labour productivity can be defined as 'GDP per worker.' Simply put, it represents the total output of a country divided by the total number of hours worked. Data, as highlighted by Meager and Speckesser (2011) 1, supports the correlation between labour productivity and wage growth.

From a microeconomic perspective, it is clear that wages are intricately tied to marginal productivity. The idea is that, as productivity increases and each hour of work generates more income over time, there is the potential for enhancing living standards on a broader scale (EPI, 2021) 2.

However, recent global trends indicate that in many countries, wages have not kept pace with the growth in labour productivity. One way to think of this is that there has been a reduction in the share of national income allocated to labour compensation. Historical analysis since 1980 reveals that, in real terms, labour productivity has outpaced wage growth over the past 22 years. It has seen an annual growth of 1.2%, while wages have only grown around 0.6% annually (ILO, 2022) 3.

The reasons for this relate to how the benefits of growth are distributed among different income classes. Depending on the policies adopted, wage growth may align or deviate from labour productivity growth. As data reveals, the policies adopted in many countries have triggered discrepancies, leading to significant income inequalities.

Even so, the statistical trends we observe regarding wage and productivity growth can vary based on how we define productivity and hourly compensation. For example, compensation may include benefits such as transport and food, holidays, and more. Therefore, the link and the degree of divergence can fluctuate depending on the method of calculation.

Final remark

The examples we've explored show how economic forces are closely connected, highlighting the labour market's sensitivity to external disruption. While macroeconomic policies help smooth job market shifts, it's equally important for individual businesses to adopt effective strategies to achieve better results. Creating specific plans to improve worker productivity, including smart compensation and benefits, can greatly boost a company's performance.

Footnotes

1. Meager, N., & Speckesser, S. (2011). Wages, productivity and employment: A review of theory and international data. (Thematic expert ad-hoc paper ). European Employment Observatory.

2. Economic Policy Institue (2021). Growing inequalities, reflecting growing employer power, have generated a productivity–pay gap since 1979.

3. Global Wage Report 2022–23: The impact of inflation and COVID-19 on wages and purchasing power. Geneva: International Labour Office, 2022.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.