Hong Kong's new Companies Ordinance (Cap. 622) (New CO), which became effective on 3 March 2014, includes a broad range of measures designed to enhance corporate governance, ensure better regulation, facilitate business and modernize the law itself. Among the measures to facilitate business reorganizations, the New CO introduces a new concept of amalgamation under court-free procedures that should allow intra-group mergers to be carried out in a simpler and less costly manner, as compared to the traditional court-sanctioned procedures. However, there is some uncertainty about the Hong Kong (and foreign) tax treatment of court-free amalgamations. Despite requests for clarification of the tax consequences of the new amalgamation procedure and/or interpretive guidelines, Hong Kong's Inland Revenue Department (IRD) has not indicated that it plans to issue guidance or practice notes. The potential tax exposure of a court-free amalgamation could be an important factor and cost when a taxpayer is assessing whether to proceed with such an amalgamation or to pursue other alternatives, such as a normal transfer of a business and assets. In the absence of clarifying guidance or amendments to the Inland Revenue Ordinance (IRO), potential tax risks and exposures could actually undermine the stated purpose of the New CO. This article looks at the potential tax issues and considers the likelihood of undesirable tax treatment.

An amalgamation is a legal process under which the undertakings, property and liabilities of two or more companies merge and are brought under one of the original companies or a newly formed company; the companies' shareholders become the shareholders of the new or amalgamated company. In the past, an amalgamation could be pursued only under a complex and costly process involving court-sanctioned procedures. As a result, amalgamations were rarely used for business reorganizations. Transfers of a business and assets, on the other hand, have been carried out more frequently, even though they may give rise to various tax exposures.

Court-free amalgamation

Under the New CO court-free amalgamation procedure, intra-group amalgamations can be carried out without having to involve a court (however, amalgamations that are more complicated still should be pursued under the court-sanctioned procedure). All of the amalgamating companies in a court-free amalgamation must be incorporated in Hong Kong and must be companies limited by shares within the same group. An "amalgamating company" is a company that is the subject of an amalgamation proposal; once the amalgamation is completed, the single continuing entity is referred to as the "amalgamated" company.

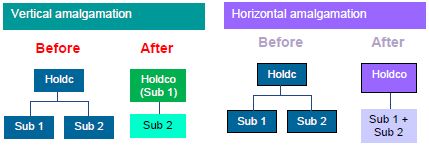

There are two types of court-free amalgamations: vertical and horizontal. A vertical amalgamation is between a holding company and one or more of its wholly-owned subsidiaries, whereas a horizontal amalgamation is between two or more subsidiaries of the same holding company. In a vertical amalgamation, the shares of the amalgamating subsidiary will be cancelled and in a horizontal amalgamation, the shares of all but one of the amalgamating subsidiaries will be cancelled. The following diagram illustrates a vertical and a horizontal amalgamation:

While minority shareholders' rights should not be a concern (since court-free amalgamations apply only to wholly-owned intra-group companies), the New CO does contain procedures to protect creditors' rights. The major procedures include special resolutions approving the amalgamation, a solvency statement to be made by the directors of each amalgamating company, a written notice to each secured creditor for consent, a public notice and a five-week period for any member or creditor to file an objection to an amalgamation.

Legal implications of court-free amalgamation

According to Section 685(3) of the New CO, the following occur on the effective date of a successful amalgamation, as specified in the Certificate of Amalgamation:

- Each amalgamating company ceases to exist as an entity separate from the amalgamated company; and

- The amalgamated company succeeds to all the property, rights and privileges, and all liabilities and obligations, of each amalgamating company.

Section 685(4) of the New CO also provides that, as from the effective date of an amalgamation:

- Any proceedings pending by or against an amalgamating company may be continued by or against the amalgamated company;

- Any conviction, ruling, order or judgment in favor of or against an amalgamating company may be enforced by or against the amalgamated company; and

- Any agreement entered into by an amalgamating company may be enforced by or against the amalgamated company, unless otherwise provided in the agreement.

These legal implications of a court-free amalgamation appear similar to those of a universal transfer (i.e. a full assignment of all assets, rights and liabilities of certain legal entities or economic units) that results in a universal succession by operation of law. Upon completion of a universal transfer, the assets of the amalgamating entities automatically are transferred to the amalgamated entity without the need for an individual contract and/or delivery of the asset, or even registration of the new ownership; accordingly, it is an efficient tool to streamline business and to conduct business restructuring. The same should be true of a court-free amalgamation, given its similarities to a universal transfer.

Uncertain Hong Kong tax exposure

Although the purpose of the New CO is to reduce the business costs of restructuring, this may not be achieved even in court-free amalgamations with a genuine commercial purpose due to the uncertainty relating to the tax treatment of such transactions. Should the IRD regard court-free amalgamations as transfers or disposals for tax purposes, a number of potential Hong Kong profits tax issues or exposures could arise. For example:

- The amalgamating company may be assessed as if its trading stock/intangible assets/fixed assets are disposed of at their fair market value; if so, deemed profits and clawbacks of previous deductions and/or depreciation allowances, as well as balancing charges, could arise.

- It is questionable whether the amalgamated company can adopt fair market value as its tax cost base for tax deduction or depreciation allowance purposes.

- Subsequent specific provisions or write offs of any accounts receivable assumed by an amalgamated company may be disallowed because the income relating to the accounts receivable was never treated as taxable by the amalgamated company.

- Tax losses of amalgamating companies may not be carried over to the amalgamated company.

- An advance ruling or agreed tax filing basis, such as offshore claims previously granted to an amalgamating company, may not be applicable to the amalgamated company.

- The amalgamating company may need to file a cessation tax return, while the amalgamated company may need to explain and make complicated tax adjustments to exclude any income and expenses from amalgamating companies that are incorporated in the amalgamated company's accounts for the year of amalgamation, to avoid double tax on any profits.

- Stamp duty may apply if the IRD considers there is a transfer of Hong Kong stock or immovable property involved in the intra-group amalgamation. (However, it is likely that the amalgamation would be eligible for intra-group relief under Section 45 of the Stamp Duty Ordinance and, therefore, the amalgamation still would be exempt from stamp duty.)

- As it is questionable whether there is a cessation of employment of staff by the amalgamating company, it is unclear whether compliance obligations would arise for both the amalgamating and the amalgamated company, including requirements to file employee cessation and commencement returns. It also is unclear how the staff of the amalgamating company would be affected, i.e. whether there would be any salaries tax impact or whether their proportionate benefits under a recognized retirement scheme would be affected.

Because of the uncertainties relating to the tax consequences of a court-free amalgamation, taxpayers contemplating such an amalgamation should request an advance ruling from the IRD to ascertain their potential tax exposure.

Arguments in support of tax-free amalgamation

Various arguments can be made in favor of the tax-free treatment of court-free amalgamations.

There would not be any undesirable tax exposure if a court-free amalgamation is deemed not to involve a transfer or disposal for tax purposes. We consider this a reasonable conclusion for the following reasons:

- Legally, amalgamation is not a transfer.

As mentioned above, the legal implications of court-free amalgamations are consistent with a universal succession by operation of law, rather than any contract of transfer; therefore, a court-free amalgamation should not be treated as a transfer for tax purposes. In addition, the New CO provides that there is no consideration involved in court-free amalgamations, and that the share capital amounts of the amalgamating companies will be merged together on amalgamation, even though the shares of all but one of the amalgamating companies are cancelled. These characteristics also are consistent with a succession by operation of law, rather than a transfer. - The New CO implies a court-free amalgamation should be

tax free.

According to Section 685 of the New CO, the amalgamated company will succeed to all the property, rights and privileges, and all the liabilities and obligations, of each amalgamating company. From this broad language, it can be inferred that, upon completion of a court-free amalgamation, the amalgamated company automatically should inherit the tax attributes of each amalgamating company, such as tax cost bases of assets and tax losses. - Precedent and similar legislation support that a

court-free amalgamation should be tax free.

Taxpayers have applied for the IRD's confirmation of the appropriate tax treatment in previous cases involving universal successions, and the IRD has agreed that the surviving entity would be regarded as if it were the merging entities for purposes of the IRO, resulting in a tax-free merger. Separate ordinances also have been enacted that provide that certain mergers of banks should be considered tax free. As court-free amalgamations have been introduced to provide a simplified and less costly way of business restructuring, it does not make sense for such amalgamations to be subject to the tax exposures discussed in the previous section.

Tax anti-avoidance and other issues after amalgamation

Because the IRO does not contain any provisions on amalgamations, there is a potential for disputes with the IRD, which may include the following:

- Application of the anti-avoidance rule

Hong Kong's general tax anti-avoidance provision, Section 61A of the IRO, empowers the IRD to disregard a transaction or to counteract the tax benefits of a transaction if the sole or dominant purpose of the transaction is to obtain a tax benefit for the person(s) who entered into or carried out the transaction, either alone or in conjunction with other persons. "Transaction" for these purposes is defined as a transaction, operation or scheme, regardless of whether such transaction, operation or scheme is enforceable, or is intended to be enforceable, by legal proceedings. With such a broad definition, it is possible that the IRD may challenge a court-free amalgamation if it considers the sole or dominant purpose of the amalgamation is to obtain a tax benefit; for example, to enable the amalgamated company to assume a significant tax loss from the amalgamating company. Therefore, it always is important to consider the tax anti-avoidance risk, and to substantiate that amalgamations are driven by genuine commercial reasons. - Change of intention

Even where there is no transfer or disposal, if the IRD regards that the intention of holding an asset changed from short-term to long-term investment upon an amalgamation, it may consider a deemed disposal to have occurred as if the trading asset had been disposed of at fair market value, and any notional gain would be subject to tax according to the Sharkey v. Wernher case principle (Sharkey v. Wernher is an old UK case in which the taxpayer appropriated trading stock for her own non-business use. The court held that the trading stock was deemed to be disposed of at fair market value for tax purposes). Conversely, if the amalgamating company had held an asset for a long-term purpose, the IRD may review the amalgamated company's intention or challenge whether there was any change of intention by the amalgamated company (i.e. from long-term to short-term investment) after assuming the assets from the amalgamating company. - Interest expense deduction by the amalgamated

company

Interest expense incurred by a holding company to raise funds to acquire the shares of a subsidiary is not tax deductible since it is not incurred in the production of the holding company's assessable profits. However, if there subsequently is a vertical amalgamation between the holding company and the subsidiary, the amalgamated company may then be able to claim a deduction for the interest expense, since the assets and business of the subsidiary have then become the assets and business of the amalgamated company. - Length of ownership period

In ascertaining whether an item is capital or revenue in nature (for example, a gain on the disposal of shares or property), the length of ownership period always is an important factor to consider. If an amalgamated company disposes of an asset that it has assumed from an amalgamating company, it is questionable whether the IRD would take into account the ownership period of the amalgamating company before the amalgamation when the IRD reviews the nature of any gain on disposal of the asset by the amalgamated company.

Foreign legal and tax issues

If an amalgamation involves assets located outside of Hong Kong or liabilities governed by foreign law, there necessarily will be foreign legal issues. In addition, foreign tax issues could arise even where all the amalgamating companies are incorporated in Hong Kong. For example, if an amalgamating company or its subsidiary has an equity interest in a PRC tax resident company, it is possible that the amalgamation may be regarded as a direct or an indirect transfer of an equity interest in the PRC tax resident company, resulting in PRC tax implications.

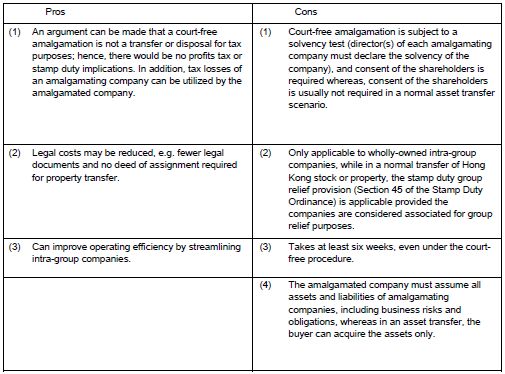

In view of the above, it is important to consider the commercial reasons, local tax implications and foreign legal and tax implications when deciding how to streamline businesses. A high-level summary of the potential pros and cons of court-free amalgamations, compared to normal asset transfers, is provided in the Appendix to this article.

Conclusion

The New CO introduces the concept of court-free amalgamations as a way to reduce business costs of intra-group restructuring. However, there are considerable uncertainties regarding the tax treatment, and without any relevant tax provisions in the IRO or guidance issued by the IRD, undesirable tax issues could result in significant costs that inhibit the purpose envisaged in the New CO. Nevertheless, we consider there are reasonable grounds to pursue a tax-free amalgamation. If this simplified way of amalgamation can be achieved without tax exposure, we believe that court-free amalgamations then could become more common for intra-group restructuring.

We welcome the introduction of court-free amalgamations as a way to facilitate intra-group restructuring that is less costly and time-consuming than the amalgamations under court-sanctioned procedures. We also look forward to the introduction of relevant tax guidance or amendments to the IRO to clarify the applicable tax treatment, which hopefully will provide for tax-free, court-free amalgamations for the reasons described above.

Appendix

Will a court-free amalgamation provide a better business restructuring tool than an intra-group asset transfer?

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.