Introduction

The term "Public-Private Partnership" or "PPP" has undergone a significant shift in recent years owing to the recent global financial and economic changes. Typically, a PPP is a contract between a private party and a government entity, for providing a public asset or service, in which the private party bears significant risk and management responsibility.1 PPP is an arrangement between a Government or statutory entity or Government owned entity, on one side and a private sector entity on the other, for the provision of public assets and/or public services, through investments being made and/or management being undertaken by the private sector entity, for a specified period of time, where there is a well-defined allocation of risk between the private sector and the public entity and the private entity who is chosen on the basis of open competitive bidding, receives performance-linked payments that conform (or are benchmarked) to specified and pre-determined performance standards, measurable by the public entity or its representative2 or earns revenues out of the operation of the asset so constructed.

PPPs are a mechanism for the government to procure and implement public infrastructure and/or services using the resources and expertise of the private sector. Where governments are facing aging or lack of infrastructure and require more efficient services, a partnership with the private sector helps foster new solutions and bring finance. PPPs combine the skills and resources of both the public and private sectors through sharing of risks and responsibilities. This enables governments to benefit from the expertise of the private sector and allows them to focus on policy, planning, and regulation by delegating day-to-day operations.3 The advantage of a PPP is that the management skills and financial acumen of private businesses create better value for money for taxpayers when proper cooperative arrangements between the public and private sectors are used.4

Effective PPPs recognize that the public and the private sectors each have certain advantages, relative to the other, in performing specific tasks. The interests of the public entity and the private sector in a PPP are different. While the public entity looks for a better economy rate of return (benefits to society) and value proposition whereas the private sector looks for financial viability and a financial internal rate of return for the project.5

Therefore, it is of paramount importance that the feasibility studies are undertaken by the public sector before floating the tender and by the private sector before submission of the bid. The key inputs from the technical feasibility study are the cost estimates (capital and O&M costs) and revenue estimates which determine the financial and economic viability of the project. The inputs have a significant impact on the implementation structure decided for the project.6

Evolution of PPP Models in the Highways Sector

After realising the need to involve the private sector in the development of roads, in 1992, the GoI amended the National Highways Act 1956 to empower GoI to levy fees for services or benefits rendered in relation to the use of sections of NH, in addition to the existing provisions for the use of ferries, temporary bridges, and tunnels. To attract private investment, the GoI initiated measures in 1994-95 like the declaration of the road sector as an industry to facilitate borrowing on easy terms and permission for floating of bonds, relaxation in Monopolies, and Restrictive Trade Practices to enable large firms to enter the highway sector and reduction in the custom duties of construction equipment.7

In 1995, the GoI amended the National Highways Act 1956 to empower itself to enter into an agreement with any person in relation to the development and maintenance of the whole or any part of a NH and entitled the person to collect and retain fees for services rendered regarding expenditure involved in building, maintenance, management and operation of the whole or part of such NH, interest on the capital invested and reasonable return.8

Evolution of Public Private Partnership Approval Committee

After identifying the lack of standard framework for the BOT mode of project execution, the Planning Commission received and scrutinized several sets of framework and model agreements for the Highways Sector between 1998-2004. Thereafter, a Committee on Infrastructure ("CoI") was constituted in 2004, which insisted on a Model Concession Agreement ("MCA") for road projects to ensure an appropriate balance of risks and obligations between parties. Thereafter, an inter-ministerial group was constituted in January 2005 to examine and evolve the MCA for (i) Build, Operate and Transfer (BOT) (Toll basis), (ii) Build, Operate, and Transfer (BOT) (Annuity basis) and (iii) Operation, Maintenance, and Tolling (OMT) projects. The Planning Commission submitted a draft MCA, which was recommended by the inter-ministerial group and was approved by the CoI as a model framework for road projects.9

Pursuant to this decision, a Public Private Partnership Approval Committee ("PPPAC") was set up under the Chairmanship of the Secretary, DEA, Secretary, PC, Secretary, Expenditure, Secretary, Legal Affairs and Secretary of the Department sponsoring a project. The Department of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Finance vide its notification dated 29.11.2005 had communicated the setting up of PPPAC.10 Thereafter, the DEA issued a notification on 12.01.2006 setting forth the detailed guidelines for formulation, appraisal, and approval procedure for approval of PPP Projects.11 The scope of the projects and their mode of implementation are decided by MoRT&H based on the viability of the projects as per the outcome of the Detailed Project Report ("DPR") or Feasibility Report ("FR").

Procedure for PPPAC approval of PPP Projects under NHDP12

1. NHDP Projects costing INR 500 Crore or more

2. NHDP Projects costing less than INR 500 Crore

Framework of PPP Models encapsulated in the MCA

At the time of setting up of the PPPAC, the prevalent MCA formulated in 2005 was used for the PPP Projects approved at the time. Thereafter, discussions between the Planning Commission and NHAI from 2006 to 2009 led to further evolution and strengthening of the framework for BOT projects. Following the discussions, the Planning Commission published the improved versions of the MCA namely; PPPs in National Highways (2009), National Highways (six laning) (2009), State Highways (2009), and Operation & Maintenance of Highways (2009).

In addition to this, the Planning Commission also published the Model Request for Qualification (RFQ) for PPP Projects, Model Request for Proposal (RFP) for PPP Projects, Model RFP for Selection of Technical Consultants, Model RFP for Selection of Legal Advisers, and Model RFP for Selection of Financial Consultants & Transaction Advisers during 2009-2010 for further strengthening of the PPP framework.13

For sustaining investor interest in the upgradation and maintenance of highways on a Design, Built, Finance, Operate, and Transfer ("DBFOT") basis, a precise policy and regulatory framework was spelled out in the MCA. The framework addressed the issues which were typically important for limited recourse financing of infrastructure projects, such as mitigation and unbundling of risks; allocation of risks and rewards; symmetry of obligations between the principal parties; precision and predictability of costs and obligations; reduction of transaction costs; force majeure; and termination. The MCA also elaborated on the basis for commercialising highways in a planned and phased manner through optimal utilisation of resources on the one hand and adoption of international best practices on the other hand.14

Need for Assessment of Project Viability

The National Highways Act, 1956 under Section 8A provides for the power of the Central Government to enter into agreements for the development and maintenance of national highways.

Section 8A(2) of the National Highways Act, 1956 states that the fee rates are fixed having regard to the expenditure involved in building, maintenance, management, and operation of the whole or part of such national highway, interest on the capital invested, reasonable return, the volume of traffic and the period of such agreement.15 Therefore, it is clear that private sector participation in infrastructure development requires a framework that can enable the private investor to secure a reasonable return at manageable levels of risk, assure the user of adequate service quality at an affordable cost, and facilitate the Government in procuring value for public money.16

The four critical elements that determine the financial viability of a highway project are traffic volumes, user fees, concession period, and capital costs. As the existing highways have dedicated traffic and the Government has prescribed the user fee for uniform application across India, revenue streams for a Project Highway can be assessed with a fair degree of accuracy. The concession period, on the other hand, can be extended only marginally for improving project viability, as the growth of traffic woud not permit very long concession periods.

Furthermore, it is submitted that the framework also provides for a balanced and precise mechanism for determination of user fees for the entire concession period since this would be of fundamental importance in estimating the revenue streams of the project and, therefore, its viability.17

Key Financial Viability Indicators and Interpretation

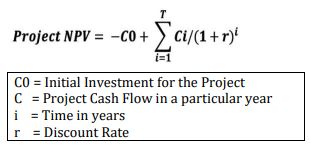

The key financial viability indicators that are most commonly used are Project Net Present Value (PNPV), Equity Net Present Value (ENPV), Project Internal Rate of Return (PIRR) and Equity Internal Rate of Return (EIRR). A positive NPV for a project when discounted at weighted average cost of capital (WACC) would mean that project returns are higher than WACC. The equation for the calculation of Project NPV is as under:18

A financially viable project should meet all debt service requirements. PIRR is the value of the discount rate (r) in the above formulae at which the PNPV is zero. Similarly, if the project investments and project cash flows are replaced by equity investments and equity cash flows, the equation would give ENPV and EIRR.19

The financial analysis is represented in terms of the cash flow statement, profit and loss statement and balance sheet.

A project could be termed financially viable (or bankable) if (i) it meets debt service obligations, (ii) the Project NPV and Equity NPV are positive, (iii) the estimated Equity IRR is more than the cost of equity. If the project is not viable on a standalone basis, the estimated support required from the Government needs to be assessed. If the support is within the acceptable range of existing Government support such as the Viability Gap Funding or other budgetary support, the project could be taken up with Government support.20

Conclusion

Therefore, in a typical PPP contract, the project viability/feasibility studies have to be carried out by the government/implementing authority in connection with the project accurately. Any inadequacy in such assessment on the part of the government/implementing authority becomes a huge pre-construction risk of the private party which can also lead to delays in implementation and heavy costs and cost overruns which would ultimately adversely affect all the stakeholders of the project.

Financial viability should be analysed in present value terms, which means that the costs and revenues over the life of the project are expressed in terms of today's money. This is essential for making meaningful comparisons of benefits and costs that occur at different times and for comparing different projects.21 In India, the PPP framework ensures that selected projects are aligned with the government's development strategy, generate the greatest economic returns for society as a whole, and do not expose the government to excessive fiscal risks. This generates greater private sector interest and public acceptance of PPP programs.

Footnotes

1 https://ppp.worldbank.org/public-private-partnership/about-us/about-public-private-partnerships

2. https://www.pppinindia.gov.in/faqs

3. Supra, note 1.

4. https://www.icao.int/sustainability/pages/im-ppp.aspx

5. The PPP Guide for Practitioners, April 2016; Department of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Finance, Government of India

6. Ibid.

7. Economic Surveys. (1994-95) available at https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/budget_archive/es1994-95/8%20Infrastructure.pdf

8. Section 8A, National Highways Act, 1956

9. Ramakrishnan. T. S, Raghuram. G; Evolution of Model Concession Agreement for National Highways in India, July 2012

10. Circular No. F.No.2/10/2004-INF dated 29.11.2005 issued by Government of India, Ministry of Finance, Department of Economic Affairs available at notification-EC.doc (notification-EC.doc (pppinindia.gov.in)

11. Circular No. F.No.1/5/2005-PPP dated 12.01.2006 issued by Government of India, Ministry of Finance, Department of Economic Affairs available at 3ee22646-ca94-478f-9cae-695a3479d83c (pppinindia.gov.in)

12. Guidelines for Formulation, Appraisal and Approval of Central Sector Public Private Partnership Projects 2013.

13. Compendium PPP Projects in Infrastructure, March 2014; Published by PPP & Infrastructure Division Planning Commission, Government of India available at http://www.gajendrahaldea.in/download/Compendium_PPP_Project_In_Infrastructure.pdf

14. Model Concession Agreement issued by the Planning Commission, Government of India, second ed:2009

15. Section 8A National Highways Act, 1956: (1) Notwithstanding anything contained in this Act, the Central Government may enter into an agreement with any person in relation to the development and maintenance of the whole or any part of a national highway. (2) Notwithstanding anything contained in section 7, the person referred to in sub-section (1) is entitled to collect and retain fees at such rate, for services or benefits rendered by him as the Central Government may, by notification in the Official Gazette, specify having regard to the expenditure involved in building, maintenance, management and operation of the whole or part of such national highway, interest on the capital invested, reasonable return, the volume of traffic and the period of such agreement.

16. Supra Note 12.

17. Ibid.

18. Supra Note 5

19. Ibid.

20. Ibid.

21. PPP Toolkit; available at https://www.pppinindia.gov.in/toolkit/ports/module2-ffaapddfvapdd.php?links=ffaapdd1g#:~:text=Financial%20viability%20should%20be%20analysed,and%20for%20comparing %20different%20projects

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.