- Sale to indirect subsidiary also covered under section 47(iv) of the Income-tax Act, 1961

- Meaning of the term 'subsidiary company' to be understood with reference to the Companies Act

Recently, in Emami Infrastructure Limited v. ITO,1 the Kolkata bench of the Income Tax Appellate Tribunal ("Tribunal") ruled that a transfer between a holding company and a 100% step-down subsidiary is not a taxable "transfer" for capital gains purposes. In doing so, the Tribunal has extended the benefit of the exemption under section 47(iv) of the Income-tax Act, 1961 ("ITA") to a step-down subsidiary as well, thereby enabling greater tax optimization while undertaking future intra-group reorganizations.

BACKGROUND

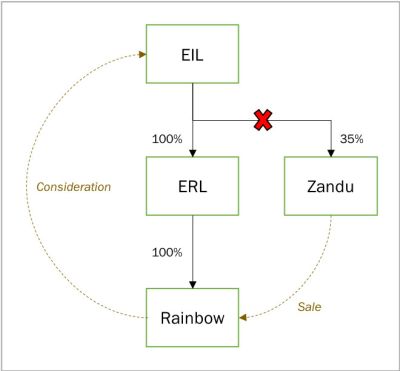

The taxpayer, Emami Infrastructure Limited ("EIL") is an Indian listed company. EIL held 100% of Emami Realty Limited ("ERL") which, in turn, held 100% of Emami Rainbow Niketan Private Limited ("Rainbow"). EIL also held 286,329 equity shares of Zandu Realty Limited ("Zandu"), a listed Indian company, representing approximately 35% of the total share capital of Zandu. During the assessment year in question (AY 2010-11), EIL sold its 35% stake in Zandu to Rainbow, and claimed long term capital loss of approximately INR 25 crores on the sale ("Transaction"). A pictorial representation of the Transaction is given below:

At the first stage of assessment, the Assessing Officer ("AO") disallowed the long term capital loss claimed by EIL on the basis that the Transaction was not undertaken at arm's length, given the significant difference between the average quoted price per share at the time of the sale (INR 3989.80) and the actual per share price at which shares were sold to Rainbow (INR 2100). The AO accordingly recomputed the capital gains arising from the Transaction by: (i) taking the average quoted price per share as the fair market value ("FMV") of the shares transferred; and (ii) deeming this FMV to be the full value consideration received by EIL from the Transaction. This resulted in a net capital gain of approximately INR 29 crore arising from the Transaction, as against the net capital loss of INR 25 crore claimed by EIL.

Aggrieved by the order of the AO, EIL appealed to the Commissioner of Income-tax (Appeals) ("Commissioner"), who confirmed the order of the AO. In addition, the Commissioner also ruled that the Transaction would not be entitled to the benefit of section 47(iv) of the ITA (which excluded transfers between a parent company and its wholly-owned subsidiary from capital gains tax),2 based on the decision of the Gujarat High Court in Kalindi Investment (P.) Ltd v. Commissioner of Income-tax3 ("Kalindi"). In Kalindi, the Gujarat High Court had ruled that the exclusion under section 47(iv) of the ITA would only cover transfers to an immediate subsidiary, and not a step-down subsidiary, based on a literal construction of the term 'subsidiary company'.

On appeal, the Tribunal reversed on both counts.

ISSUES BEFORE THE TRIBUNAL

After hearing counsel for both parties, the Tribunal framed two issues for consideration:

- Whether the Transaction constituted a "transfer" in view of section 47(iv) of the ITA; and

- If yes, whether the AO was correct in substituting the actual sale consideration received with FMV of shares sold.

RULING OF THE TRIBUNAL

Relying on the decision of the Bombay High Court in Petrosil Oil Co Ltd v. Commissioner of Income-tax4 ("Petrosil"), the Tribunal observing that since the term 'subsidiary company' had not been defined under the ITA, it would have to be understood in accordance with the meaning given to it under the Companies Act. Despite noting the conflicting decision in Kalindi, the Tribunal felt that a 100% step-down subsidiary would also qualify as a "subsidiary company" for the purposes of section 47(iv), since that was "the letter and spirit of the enactment."5 Hence, the Transaction could not be regarded as a "transfer" for the purposes of charging capital gains tax.

By consequence, the question of computing either capital gain or capital loss did not arise. For the same reason, the Tribunal did not go into the question of whether the AO was correct in substituting the actual sale consideration received with the FMV of shares sold.

ANALYSIS

The ruling of the Tribunal is certainly a welcome one and will go some way in giving a boost to internal reorganizations involving wholly owned indirect subsidiaries. The Tribunal has provided no additional justification or reasoning for following the decision in Petrosil, besides stating that as per the "letter and spirit" of section 47(iv), transfers to a step-subsidiary would also be covered by that section. It is important to note that Petrosil was not decided in the context of section 47(iv), but in the context of section 108 of the ITA (which has since been omitted) and that6 it was in that context that the Bombay High Court had imported the meaning of the term 'subsidiary company' from the Companies Act, 1956 into the ITA.

By contrast, the contradictory ruling in Kalindi was delivered on nearly identical facts as Emami, and can therefore be argued to have been the appropriate precedent applicable in this case. Kalindi concerned a taxpayer earning dividend and interest income from its activities of making or holding investments, and from financing industrial enterprises. For the assessment year in consideration, the taxpayer sold its shareholding in a private limited company to its 100% step-down subsidiary, and claimed a short-term capital loss from the sale in its return of income. Before the Gujarat High Court, counsel for the taxpayer argued that section 47(iv) had to be construed strictly: since the taxpayer did not hold any shares of the transferee, section 47(iv) would have no applicability, and the sale would amount to a "transfer" for capital gains purposes.7 It was also argued that the meaning of the term 'subsidiary company' could not be imported from the Companies Act, 1956 since section 4 of that Act, which defined the term 'subsidiary company', expressly began with the words "For the purposes of this Act".8 The Gujarat High Court agreed on both counts:

"As we have already indicated earlier, section 4 makes it clear that the expanded definition of 'holding company' is applicable for the purposes of the [Companies] Act (...) The [Income-tax] Act has carved out a smaller number of holding and subsidiary companies for the purposes of section 47(iv) and (v). The wider definition of a 'holding company' with emphasis on 'control' as the guiding factor is not adopted in clauses (iv) and (v) of section 47. It is specifically provided that the parent company or its nominees must hold the whole of the share capital of the company. The Legislature while enacting the [Income-tax] Act, therefore, made a clear departure from the definition of 'holding company' as contained in the [Companies] Act. In this view of the matter, there is no justification for invoking clause (c) of sub‐section (1) of section 4 while interpreting the provisions of clauses (iv) and (v) of section 47, which lay down two specific conditions for applicability of the said clauses and which are quite different from the criteria laid down in sub‐section (1) of section 4 of the Companies Act, 1956, for giving a more expanded definition of a 'holding company' to subject more companies to regulatory control under the Companies Act. On the other hand, the object underlying section 47 is to lay down exceptions to the legal provision (section 45) for taxing gains on transfer of capital assets. The general rule is to construe the exceptions strictly and not to give them a wider meaning." [Emphasis supplied]

On this basis, the Gujarat High Court accepted the taxpayer's argument that section 47(iv) would have no applicability in case of transfers to a 100% step-down subsidiary.

It is an accepted canon of interpretation that where a rule is capable of being interpreted more than one way, the interpretation that favours the taxpayer is to be given effect.9 The ruling in Emami represents a curious departure from this principle. Had it been held that the Transaction was not covered by section 47(iv), the taxpayer could potentially have claimed short term capital loss on the sale, which would consequently have resulted in greater benefit to the taxpayer than otherwise. While the ruling of the Tribunal in this case appears to be at odds with what equity may have necessitated, it is possible that in a wide variety of cases, making such transfers non-taxable would benefit a significant number of taxpayers.

The ruling has also appears to raise interpretational issues vis-à-vis section 47A of the ITA. Per s. 47A(1)(ii), if the parent company or its nominees ceases to hold the whole of the share capital of the subsidiary company before the expiry of eight years from the date of transfer, the exemption under section 47(iv) would be withdrawn retrospectively. Since the present case involved a transfer to a step-down subsidiary (and not a direct subsidiary), one possible interpretation is that section 47A would be attracted if: (a) the parent sold shares of the subsidiary; or (b) the subsidiary sold shares of the step-down subsidiary within eight years of the date of transfer. A second way of interpreting the applicability of section 47A would be to argue that so long as the parent company indirectly holds the whole of the share capital of the step-down subsidiary, the identity of the intermediate subsidiary company would be irrelevant, and any change of ownership at the intermediate level should not attract section 47A. On balance, this second interpretation should be the correct view, given that the intention behind section 47(iv) is to enable tax-neutral internal reorganizations.

More generally, in view of the conflicting decisions on whether the meaning of the term 'subsidiary company' under the Companies Act can be imported into the ITA, taxpayers continue to have the ability to rely on different decisions to support a position that is beneficial to them. A taxpayer wishing to claim capital losses would argue that the term 'subsidiary company' ought to be interpreted strictly, while others who might be subject to capital gains tax would argue for a liberal interpretation of the term based on the Companies Act definition. The interpretation of the term 'subsidiary company' cannot rest mainly upon what is beneficial to the taxpayer on a case to case basis, and therefore requires a final ruling by the Supreme Court to settle this issue and provide the required certainty.

Footnotes

1 Order dated 28-02-2018 in ITA No. 880/Kol/2014.

2 section 47(iv), ITA:

"Nothing contained in section 45 shall apply to the following transfers:

(...)

(iv) any transfer of a capital asset by a company to its subsidiary company, if –

(a) the parent company or its nominees hold the whole of the share capital of the subsidiary company, and

(b) the subsidiary company is an Indian company;".

3 [2002] 256 ITR 713 (Gujarat).

4 [1999] 236 ITR 220 (Bombay).

5 Supra note 1, at para. 17.

6 section 108 has been omitted with effect from April 1, 1988:

"108. Savings for company in which public are substantially interested — Nothing contained in section 104 shall apply—

(a) to any company in which the public are substantially interested; or

(b) to a subsidiary company of such company if the whole of the share capital of such subsidiary company has been held by the parent company or by its nominees throughout the previous year."

7 Kalindi, [2002] 256 ITR 713 (Gujarat), at para. 5.1.

8 Kalindi, [2002] 256 ITR 713 (Gujarat), at para. 5.2. Similarly, the definition section under the Companies Act, 2013 (i.e. section 2) begins with the words "In this Act, unless the context otherwise requires".

9 See IRC v. Duke of Westminster, [1936] AC 1; CIT v. Vatika Township P. Ltd., 2015 (1) SCC 1; CIT v. Shaan Finance (P.) Ltd, [1998] 231 ITR 308 (SC); Commissioner of Income-tax v. Swadeshi Match Co, [1983] 139 ITR 833 (Bombay).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.