The South African Supreme Court of Appeal ("SCA") recently handed down an important judgment that covers a lot of IP law. The procedural aspects of Quad Africa Energy (Pty) Ltd v The Sugarless Company (Pty) Ltd and Another are specific, complex and hard to follow. We therefore feel that the best way to report on this judgment is to focus on some of the major legal issues that were discussed.

Facts

An Australian company, The Sugarless Company ("TSC"), sells confectionery under the trade mark Sugarless in packaging that has certain design features. TSC has a South African trade mark registration for the S SUGARLESS logo in class 30 covering confectionery.

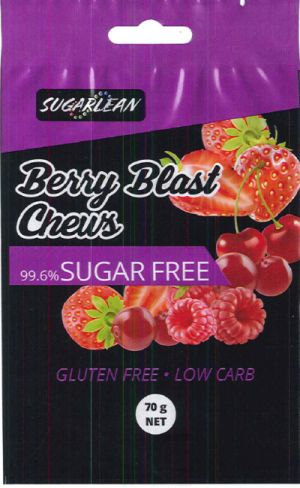

TSC appointed a South African company, Quad Africa Energy ("QAE"), as its exclusive distributor for South Africa. When QAE launched a competing product under the name Sugarlean in packaging with arguably similar design features, TSC issued legal proceedings.

TSC claimed infringement of a South African trade mark registration, passing off, copyright infringement and counterfeiting. QAE denied all allegations and contended that the trade mark registration should be subject to a disclaimer of the word "sugarless". TSC was successful in urgent proceedings and the case eventually ended up in the SCA.

QAE initially launched the Sugarlean product using the first packaging. That packaging was then amended to the new packaging, and then further amended to the future packaging.

Above: First packaging

Above: New packaging

Above: Future packaging

Scope of appeal proceedings

QAE did not appeal the finding that the first packaging amounted to trade mark infringement, copyright infringement, passing off and counterfeiting. QAE also did not appeal the finding of trade mark infringement in the new packaging. What they did appeal against was the finding of copyright infringement in the packaging, passing off, and counterfeiting, based on the new packaging and future packaging.

Below, we discuss some interesting aspects of the SCA judgment.

Should there be a disclaimer against the word "sugarless"?

Seemingly a lover of etymology, Judge Ponnan explained that the word was in use at least as early as 1785, when the poet William Cowper wrote to reverend John Newton to say that "it would have been as well if neither my old friend had recorded his eructations, nor the Doctor his dishes of sugarless tea, or the dinner at which he ate too much."

Possibly inspired by this foray into 18th century speech, the judge went on to say this: "It brooks of no doubt that the term 'sugarless' is inherently incapable of distinguishing one person's confectionery goods from another's. No amount of use of a purely descriptive term can make it distinctive."

The judge referred to the recent SCA judgment of Cochrane Steel Products (Pty) Ltd v M-Systems Group (Pty) Ltd and Another. That case involved the trade mark Clearview for fencing and court there said that "this case calls out for a disclaimer... traders should not be put to the trouble and expense of manufacturing and selling their products and then be subjected to the risk of infringement litigation where the Act has provided a mechanism to provide certainty."

So, a disclaimer of exclusive rights to the word sugarless was entered.

Are the trade marks Sugarless and Sugarlean confusingly similar?

The judge dismissed the argument that the marks Sugarless and Sugarlean are similar because only the last two letters differ. He said that this "is not the way the average consumer interested in the products would perceive things...visually, phonetically and aurally both marks are different."

He went on to say this: "In any event when descriptive terms are used as trade marks, the court will accept comparatively small differences as sufficient to avert confusion and, what is more, a measure of confusion is accepted."

Was there passing off?

The SCA held that QAE's packaging or get-up was not calculated to confuse or deceive. The main similarity between the get-ups was the colour black in the packaging and the presence of fruit or other devices. But, said Judge Ponnan, there was nothing wrong with that "given the plethora of confectionery products in the market which utilise that colour" and the obviously non-distinctive nature of the devices.

Was there copyright infringement?

The judge said that TSC's label was clearly an original artistic work that qualified for copyright protection, but had QAE made a reproduction or adaptation of that artistic work?

The new packaging was clearly not a reproduction, but was it an adaptation? In other words, "a transformation of the work in such a manner that the original or substantial features thereof remain recognisable."

Judge Ponnan said that "if the average person would confuse the new work with the original work then there is a strong likelihood that a court would find that there had been an adaptation." He warned against an over-astute "dissection of the packaging". He concluded that there was no "objective similarity" in this case, and none of the "slavish copying or clumsy adapted plagiarism' that earlier judgments have spoken of.

Had there been counterfeiting?

The first court had found that there had been counterfeiting but, said Judge Ponnan, it had done so "without at all considering the requirements for counterfeiting." These requirements have previously been described by Judge Harms as being "not the same as copyright or trade mark infringement." Judge Harms went on to say that counterfeiting "requires more...this appears to be logical, because 'to counterfeit' ordinarily means to make an imitation of something in order to deceive, or to make a copy of something."

Judge Ponnan went on to say this: "As I have found that neither the claim of breach of copyright, nor that of trade mark infringement has been made out in relation to the packaging" there had been no counterfeiting.

To end off

This judgment covers a great deal of IP law and is likely to be influential in future court decisions.

Reviewed by Gaelyn Scott, Head of ENSafrica's IP department.

Originally published 05 May 2020

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.