1 Introduction

The Digital Markets Act (the "DMA") was published in the Official Journal of the European Union on 12 October 2022 and entered into force on 1 November 2022. Large digital platforms that offer core platform services ("CPS") will be subject, as "gatekeepers", to extensive regulatory measures by the European Commission (the "Commission")1.

The BigTech companies, which appear to be the main target of this regulation, will be required to do what the DMA mandates in order not to face any competition law sanctions, or otherwise they will be adjusting their operations to escape from the scope of application of the DMA. In either case, the lives of the BigTech companies will never be the same. However, if the latter path is followed, the practice of adjusting operations to evade the application of the DMA may inspire antitrust cases against platforms that do not have gatekeeper status, but which have a dominant position.

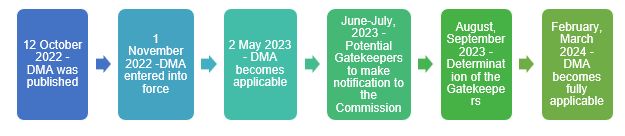

Leaving the implications aside (further analysed below), the DMA will start to apply from 2 May 2023, at which point undertakings meeting the criteria for gatekeepers will have two months to notify the Commission. Once they are designated as gatekeepers by the Commission, they must adhere to the DMA's dos and don'ts after a period of six months. This will be the case from around March 2024. Please see below a diagram indicating the timeline:

2 Purposes of the DMA

The DMA aims to address concerns regarding contestability and fairness in the digital economy, introducing a number of per se prohibitions and obligations on big technology companies. To this end, the DMA is aimed at large digital platforms that offer CPS, have a significant impact on the digital economy and have an entrenched and durable position on the market.2

2 Services subject to the DMA

The DMA regulates certain online services that serve as important interfaces between large numbers of users and businesses. The CPS consist of online intermediation services, online search engines, online social networks, video sharing platform services, messenger services (number-independent interpersonal communication services), operating systems, web browsers, virtual assistants, cloud computing services and online advertising services.

3 Who are the "gatekeepers"?

The Commission will designate as gatekeepers certain providers of core platform services that meet a number of criteria where the DMA will only apply to gatekeepers. The test relies on three qualitative criteria, which are presumed to be satisfied if three quantitative thresholds are met. Thus, only the biggest players will be appointed as gatekeepers. It mentioned during the legislative process that the DMA was to apply primarily to companies such as Google, Apple, Meta, Amazon and Microsoft.

The provider of a CPS will be designated as a gatekeeper, if it meets a cumulative three criteria test as set out in the table below:

Gatekeeper Criteria |

|

Qualitative |

Quantitative |

|

Size criteria (having a significant impact on the internal market) |

EU-wide turnover of EUR 7.5 billion in each of the last three financial years, or a fair market value valuation of EUR 75 billion, AND provides the same CPS in three EU Member States |

|

Gateway criteria (provide a service which is an important gateway for business users to reach end users) |

CPS with at least 45 million monthly active end users AND at least 10,000 annual active business users |

|

Durability criteria (enjoy an entrenched and durable position, or will enjoy it soon) |

The gateway criterion has been met in each of the last three financial years |

Companies that satisfy the above quantitative criteria are presumed to be gatekeepers but have the opportunity to rebut the presumption and submit substantiated arguments to demonstrate that, due to exceptional circumstances, they should not be designated as a gatekeeper despite meeting all the thresholds. The Commission may launch a market investigation to assess in more detail the specific situation of a given company and may decide, nonetheless, to designate the company as a gatekeeper on the basis of a qualitative assessment, even if it does not meet the quantitative thresholds.

Thus, the question is what happens if the undertaking is not above the quantitative thresholds, but looks like it can become a gatekeeper. If the commission decides to qualify that kind of undertaking as a gatekeeper after the qualitative designation procedure, it may go against the main objectives of the implantation of the DMA, which are the contestability and fairness defined in the DMA in itself.

4 Dos and Don'ts for the Gatekeepers

For each of their CPS identified in the relevant designation decision, the gatekeepers must comply with the obligations set out under Articles 5, 6 and 7 of the DMA.

The rules list those business practices that the EU legislators found to be problematic (i.e. the don'ts) when used by gatekeepers with regard to their CPS, as well as the ways in which the EU legislators wanted to require gatekeepers to behave (i.e. the dos). Article 5 of the DMA sets out requirements that are applicable without further specification, while the obligations under Article of the DMA are also directly applicable, but can be further specified by the Commission for the relevant gatekeeper. Article 7 of the DMA includes far-reaching interoperability obligations for messenger services.

The gatekeeper obligations of the DMA are, in principle, self-executing, which means gatekeepers are required to take and implement necessary actions by themselves. To ensure compliance with the DMA they must, inter alia, establish a compliance unit. This issue is of significance as such companies will be subject to audit and reporting obligations that place the burden of proof on them for compliance with the DMA.

5 What are the consequences of non-compliance?

a) Fines

Fines of up to 10% of the company's total worldwide annual turnover, or up to 20% in the event of repeated infringements

b) Periodic penalty payments

Fines of up to 5% of the average daily turnover

c) Remedies

In case of systematic infringements of the DMA obligations by gatekeepers, additional remedies may be imposed on the gatekeepers after a market investigation. Such remedies will need to be proportionate to the offence committed. If necessary and as a last resort option, non-financial remedies can be imposed. These can include behavioural and structural remedies, e.g. the divestiture of (parts of) a business.

6 DMA Implications in the Digital Markets

Economists and competition law experts from all around the world have raised concerns as regards the difficulties in the practical implementation of the DMA. From an economic aspect, the criteria to qualify as a gatekeeper have many variants and it is not a "simple counting exercise". The final text and the annex of the DMA did a remarkable job and contain detailed information, but they fail to determine what is going to count and how it is going to be counted when it comes to calculation. In practice, this problem will grow into a bigger issue because, like all antitrust analyses, it is going to be a nightmare to determine the market share, business structures and divisions of a business. Thereby, even though quantitative thresholds seem to be administratively convenient, they will be economically impractical.

Further, the debate about proportionality is a tiebreaker question among the practitioners. While the DMA is designed and required under EU law to be proportionate, the application of its obligations to the gatekeepers is at risk of being disproportionate. On one hand, the measures provided by the DMA may be effective, but on the other hand, they may be more than what needs to be regulated in the digital market. A failure to maintain proportionality is too great a cost given the objectives of the DMA. The DMA is based on the fairness and contestability objectives, but specific compliance with the literal wording of the obligations may contravene the intentions of these objectives as the big technology companies will be stressed by the close scrutiny of the Commission.3

As a natural market reaction, platforms may seek strategies to make their products difficult to contest, to reduce the contestability of their operations. The Commission officials suggest that in such a situation, the DMA will be supplemented by traditional competition law, i.e. abuse of dominance proceedings will be initiated. Further, any competition proceedings due to such situations are likely to enhance the iteration and application of DMA regulations.4

7 The DMA's effect on other jurisdictions

The DMA may result in the adoption of "platform laws" in other jurisdictions. We are already seeing examples of similar legislation in Germany and South Korea. The UK and Australia are also working on their own solutions.

A draft amendment law amending Competition Law No 4054 of the Republic of Türkiye has been shared with certain institutions/entities for receiving opinions on the coverage of contemplated digital markets regulations and several other issues.

Footnotes

1. European Commission website, Questions and Answers: Digital Markets Act: Ensuring fair and open digital markets (link: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/QANDA_20_2349)

2. Ryan Browne, "EU targets U.S. tech giants with a new rulebook aimed at curbing their dominance" published on CNBC website (link: https://www.cnbc.com/2022/03/25/digital-markets-act-eu-targets-big-tech-with-sweeping-new-antitrust-rules.html)

3. Chloe Olivia Sladden, "What is the Digital Markets Act?" published on Verdict's website (link: https://www.verdict.co.uk/what-is-the-digital-markets-act/)

4. Regulation (EU) 2022/1925 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 September 2022 on contestable and fair markets in the digital sector and amending Directives (EU) 2019/1937 and (EU) 2020/1828 (Digital Markets Act) (Text with EEA relevance)

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.