Introduction: Gas demand in Turkey and gas import routes of Russia

For countries that do not have their own gas deposits, import dependency turns out to be a substantial concern. Not only the potential will and the ability of the resource-holder countries to use natural gas as a political weapon, but also the political instabilities in the transit countries have been one of the issues that raise concerns in the consuming countries. These concerns led the consuming countries to search for stable suppliers with safe routes for delivery.

It is not a big surprise when Turkish policymakers embrace energy pipeline projects that trespass Turkish territory especially towards Europe where the real stable and cash-paying energy market is believed to exist. Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan crude oil pipeline, the South Caucasus Gas Pipeline, Blue Stream Gas Pipeline, failed Nabucco and TANAP are among the projects that Turkey has enthusiastically supported.

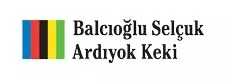

Two policy goals seem overlapping here: First, becoming not only a transit (physical) country but also an energy hub (financial) where price formation takes place; second, meeting the growing gas demand in the domestic market.1 For not only power generation, Turkey also needs natural gas for industrial usage and district heating as well. However, this gas has to be imported since domestic deposits (less than 1 percent) are far from satisfying the domestic demand. Turkey imports natural gas from Russia, Iran and Azerbaijan through pipelines and from Algeria and Nigeria in the form of LNG.

Russia, on the other hand, has traditionally been the main gas supplier to Europe through historical pipelines and direct lines such as Nord Stream that directly ties Russian reserves with the German market.

The "Brotherhood" pipeline is the largest gas transportation route. It can carry more than 100 bcm gas per year, transiting Ukraine and running to Slovakia. In Slovakia, the pipeline is split and one branch goes to the Czech Republic. Russian gas transported through the Czech Republic flows in the direction of Waidhaus and Hora Svaté Kateřiny via Uzhgorod, as well as from the Yamal-Europe gas pipeline, with Olbernhau and Brandov as entry points. Its second branch goes to Austria. This country plays an important role in the delivery of Russian natural gas to Italy, Hungary, Slovenia and Croatia. Gas deliveries through this pipeline started in 1967.

The Yamal-Europe pipeline runs across Russia, Belarus and Poland reaching Germany. Its length is beyond 2,000 km; 14 compressor stations are operational along it. The pipeline construction began in 1994 close to the German and Polish borders, and first sections of the pipeline were brought online as early as in 1996. The Belarusian part where Gazprom has become the sole investor was commenced in 1997. Upon commissioning of the last compressor station in Yamal in 2006, Europe reached full capacity — 33 bcm per annum.

The gas transportation route through Romania carries Russian gas to this country, transiting Ukraine and Moldova, and runs further to the Balkan countries and Turkey. The pipeline construction began in 1986, and the second line was added in 2002.

The Blue Stream is intended for direct gas deliveries to Turkey, bypassing transit countries. The 1,213-km-long gas pipeline consists of an overland and offshore sections, starting close to Izobilnoye in Stavropol Region, and ending in Ankara, Turkey. The offshore section of Blue Stream is unique in its design and construction, the subsea pipe being 393 km long. The construction was completed in December 2002, and February 2003 marked the start of the first commercial gas flow.

Furthermore, the consumers in Finland receive Russian gas through the gas transportation system in the Leningrad Region.

The Nord Stream offshore pipeline laid on the bottom of the Baltic Sea with capacity of 55 bcm per year allows direct gas transportation for clients in Western Europe, primarily in Germany, bypassing transit states.

On September 1, 2014, the first joint of the Power of Siberia gas transmission system was welded in Yakutsk. This pipeline system will convey gas from the Yakutia and Irkutsk gas production centers to the Far East and China. It will have an annual capacity of 38 bcm of gas. By late 2018, a 2,200-kilometer pipeline section will be built to connect the Chayandinskoye field in Yakutia to the city of Blagoveshchensk on the Russian-Chinese border.

Alternative routes for Europe and Russia's policy to bypass Ukraine

The European energy policy faces three fundamental challenges, and the policies shaped have to address these challenges at the same time.

- Security of supply

- Successful energy transition

- Competitiveness

The faster than expected decline in Europe's gas reserves and accelerating tensions with Russia are the two main sources of security of supply concerns. Shale gas potential in Europe is still far from being a game changer as it is in the US. Thus, EU gas demand is still being primarily met by Russian supply and alternative routes for Europe still mean non-Russian routes.

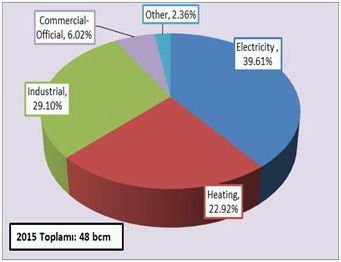

Gas demand in EU has been declining since when it peaked in 2010. Indeed, EU gas demand has rapidly fallen since 2010: Demand in 2013 was 14 percent lower than 2010 levels and this despite 2013 being colder than normal. Demand fell by a further 11 percent in 2014, which was an exceptionally mild year. In 2014, gas demand was the lowest it has been since 1995. Eurogas estimated that every member state saw a decrease in gas demand between 2013 and 2014, in great part because of mild temperatures.

Demand is expected to grow in the long run as the European economies catch up with their traditional growth levels, and there is little evidence that the EU countries will do away with the nuclear phase-out started after Fukushima. The upper-bound projection from Eurogas is for an increase in consumption of more than 50 percent by 2035 compared to current levels, and even their lowest estimate represents a 15 percent increase on 2014. Latest projections of the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Gas (ENTSO-G), used to plan gas pipeline investment, range from a 13 percent increase in EU gas demand to 2030 in its lowest scenario, to a 35 percent increase by 2030 in its high scenario.2

In order to address the security of supply concerns, the EU should work on two distinct scenarios: A total cut in Russian deliveries (source disruption) and disruptions attributable to transit countries (transit disruptions), i.e. Ukraine or Belarus. Thus, reducing the overall dependence on Russian supplies and/or on instable transit routes are concurrent policy objectives of the EU if resilience towards disruptions in the supply is to be handled beyond storage capabilities of the Union.

Facing reduced domestic production, desire to reduce dependency on Moscow, limited prospects for EU shale gas and increasing concerns on the sustainability in North African supplies, developing alternative gas routes to Europe has become increasingly important. Significant efforts were made in 2015 to promote the development of the "Southern Gas Corridor" and to increase supplies from countries in the Caspian, as borne out by the Ashgabat Declaration signed in May 2015 between Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, Turkey and the EU. The "Southern Corridor" projects will pipe natural gas from Azerbaijan (10 bcm to the EU via the Trans-Adriatic pipeline, as of 2018). In the long term, the corridor could transport important resources from Turkmenistan, Iran and Iraq.

In sum, although EU-wide gas demand has been stagnant for the last decade, non-Russian supplies are still policy priorities for EU policy-makers. Meanwhile, bilateral business between Russia and Germany through Nord Stream (and now through planned Nord Stream 2) have been leading questions about the solidarity in the Union while increasing reactions of particularly east and central European countries against the Union. Most of these countries are almost 100 percent dependent on Russian gas, and projects bypassing their territory seem to increase their security of supply concerns.

Most recently, eight European leaders—representing Poland, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Romania—sent a letter of protest to European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker expressing opposition to Russia's planned Nord Stream-2 gas pipeline. The letter, dated March 7, warned that Nord Stream-2 would have "potentially destabilizing geopolitical consequences," undermine the energy security of Central and Eastern Europe, and detrimentally affect Ukraine.3

It is no secret that Russia desires to pursue energy relations with EU countries on a bilateral basis rather than facing EU as a block. Through Nord Stream 1 and Nord Stream 2, Russia proved that it is not an unachievable goal.

Turkish Stream

After failing to accomplish concrete steps in realizing the South Stream project and witnessing that Azeri gas will feed Europe markets through TANAP project, Russia declared to cooperate with Turkey and reach European markets through Turkish EEZ bypassing Ukraine. It is no secret that Turkey wants to include other gas sources in TANAP, especially Turkmen gas.4 In addition, elimination of sanctions on Iran, prospects for Iraqi gas and potential that Israeli gas will reach markets through Turkey all represent potential contributions to fill TANAP other than with Azeri gas.

Meanwhile, political relations between Russia and Turkey swing from one edge to another. During the strained period with Russia, Turkish policymakers had to explore alternative gas supplies to get prepared for possible disruptions in the gas flow from Russia. Preparations included a MoU with Qatar to receive Qatari gas in the form of LNG. Indeed, the announcement of a possible direct line between Turkey and Russia underneath the Black Sea to feed the European market appeared when energy collaboration between the two countries was in its honeymoon including the existing gas business and nuclear power plant project. Announced by Russian president Vladimir Putin on 1 December 2014, during his state visit to Turkey, the proposal is supposed to replace the earlier cancelled South Stream project.

However, the incident of the Russian jet that was shot down had an extreme impact on relations between Turkey and Russia. Following the incident, talks on the project were unilaterally suspended by the Russian side, and in December 2015, Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan announced the Turkish Stream project would be formally abandoned.

Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov told reporters that Russian President Vladimir Putin received a letter from Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in June 2016 expressing his "deep condolences" to the family of the pilot who was killed. In the same letter, Erdogan also pledged that he would do "everything possible" to restore relations with Russia. Presidential spokesperson Ibrahim Kalin confirmed that Erdogan sent the letter saying he was "sorry" for the incident, which took place on November 24, 2015 when Turkey shot down the Russian jet violating its airspace and which culminated in the breakdown of bilateral relations.5

In parallel with the above normalization track with Russia, Turkey started to rebuild relations with both Israel and Egypt that had been almost completely collapsed during the era of Davutoğlu. Prime Minister Binali Yildirim indicated that a similar process of reconciliation could occur in Turkish - Egyptian relations.6

Under this political rapprochement environment between Turkey and the countries mentioned came the coup attempt on 15 July 2016 during which the support of Russia was said to be influential if not decisive. It is no secret that the path to July 15 and the aftermath made Erdogan "too close to Russia"7 while relations with its NATO partners have been restrained.

The rapprochement yielded it benefits earlier than expected since the potential areas for cooperation and projects have already been well known by the parties. The process for the construction of the nuclear power plant accelerated, cooperation and a mutual understanding in Syria developed, tourists from Russia started to arrive in Turkish airports again and barriers to exports from Turkey to Russia have been eliminated. Amidst these cozy bilateral steps, an announcement for the signing of the intergovernmental agreement between Russia and Turkey for building the Turkish Stream came during the 23rd World Energy Congress held in Istanbul 9-13 October 2016.

"You have now witnessed the signing of the intergovernmental agreement on the construction of the Turkish Stream." Putin said at the press conference following the signing of the agreement. The energy ministers of the two countries signed the agreement. Gazprom CEO Alexey Miller said that the Turkish Stream project agreement envisioned the construction of two pipeline branches, each with a capacity of 15.75 billion cubic meters (bcm). The first branch will supply gas directly to Turkey, while the second is to be used to deliver gas to European countries through Turkey, he explained. "The intergovernmental agreement would also define the deadline by which the two maritime threads are to be built. It's December 2019," Miller said. Russia will construct and own the maritime stretch of both Turkish stream branches, Novak said. The land part of the branch, supplying gas to Turkey, will belong to a Turkish company, with a joint venture to be created which will assume ownership of the transit pipeline, he added.8

Conclusion

The rapprochement between Russia and Turkey seems more robust than ever since now it comes at a price. Relations with NATO allies swiftly deteriorated especially after the coup attempt in Turkey. It also seems that now there is a consensus on the untrustworthiness of NATO allies and on the need to have closer strategic relations with Russia among Turkish political elite. We may witness more projects with regional affects realized in cooperation with Russia and Turkey in the near future.

Undoubtedly, one of the architects of swift normalization of the energy relations with Russia is the new energy minister of Turkey, Berat Albayrak. In addition to the pragmatic attitudes of the prime minister Binali Yildirim, the target-oriented approach of the energy minister can be said to accelerate the realizations of the projects.

As part of this project and the broadening of the cooperation between the countries, parties also agreed on a mechanism by which to provide a discount on gas for Turkey. As we discussed, Turkey is heavily dependent on gas, and its economy is highly sensitive to the gas prices. This discount after the Iranian discount took place a few months ago will likely positively affect the Turkish economy.

Having said that the rapprochement came at a price, Turkey has yet to receive the receipt of this price. Regional politics is more slippery than one can predict; thus, each step should be thought through more than twice. The receipt should be payable.

Footnotes

1. Natural gas consumption in 2015 was 48 bcm, and based on EMRA forecast it will be 49.5 bcm.

2. Dave Jones, Manon Dufour, Jonathan Gaventa, "Europe's Declining Gas Demand: Trends and Facts on European Gas Consumption," E3G, June 2015.

4. "TANAP'a Türkmen gazının dahil olması için çalışıyoruz.", Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan stated Atlantic Council Energy and Economy Summit in November 18-20 2015.

5. "Erdogan 'sorry' for downing of Russian jet," Al Jazeera, 27 June 2016, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2016/06/turkey-erdogan-russian-jet-160627131324044.html

6. "Turkish Foreign Policy after Davutoglu: Continuity vs. Rupture", Galip Dalay, Aljazeera Center for Studies, 14 July 2016 http://studies.aljazeera.net/en/reports/2016/07/turkish-foreign-policy-davutoglu-continuity-rupture-160714100039252.html

8. https://www.rt.com/business/362279-gazprom-turkish-stream-pipeline/

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.