Keywords: ECJ ruling, Brussels I Regulation, EU Rules, contractual disputes, commercial business, Europe, Article 22.2

ECJ ruling on the scope of Article 22.2 of the Brussels I Regulation:

In disputes in which a company argues that a contract cannot be relied upon against it on the basis that a decision of its organs which led to the conclusion of the contract is invalid, Article 22.2 does not apply so as to allocate "exclusive jurisdiction" to the Courts of the EU Member State in which that company has its seat.

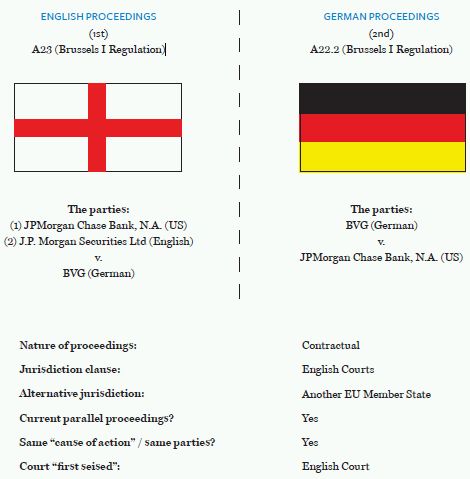

The scenario:

Summary

THE CASE:

The Court of Justice of the EU ("ECJ") has delivered a key decision in Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe (BVG) Anstalt des öffentlichen Rechts v JPMorgan Chase Bank NA, Frankfurt Branch (Case C-144/10).

That decision concerned the EU rules for determining in which country's Courts contractual disputes should be heard. It is of crucial significance for those conducting commercial business in Europe.

THE ISSUE:

In proceedings which have as their object the "validity of decisions of organs" of a company, legal person or association, Article 22.2 of Council Regulation (EC) No. 44/2001 (the "Brussels I Regulation") allocates "exclusive jurisdiction" to the Courts of the EU Member State in which that company, legal person or association has its seat. An equivalent provision is found within the Lugano Conventions which apply as regards Iceland, Norway and Switzerland.

Upon a reference by the German Courts, the ECJ was asked whether Article 22.2 of the Brussels I Regulation applied to proceedings in which a company asserted that a contract is invalid/unenforceable because the decision of its organs to enter into it were invalid. In other words, might the Courts of the seat of a company have "exclusive jurisdiction" to hear claims of a contractual nature in which that company raised ultra vires or similar arguments?

Following the financial crisis, such arguments, commonly comprising assertions of lack of capacity and/ or lack of authority, have been advanced by a number of entities seeking to extricate themselves from contracts. Consequently, equivalent jurisdictional issues have also arisen in a string of other recent cases, including:

Calyon v Wytwornia Sprzetu Komunikacynego PZL Swidnik SA ("PZL") [2009] (English Commercial Court, London) and PZL v Calyon (parallel proceedings before the Commercial Division of the Polish Regional Court, Warsaw);

- Depfa Bank plc v Provincia di Pisa / Dexia Crediop S.p.A. v Provincia di Pisa [2010] (English Commercial Court, London) and parallel Italian proceedings (before the Administrative Court for the Region of Tuscany); and

- UBS AG, London Branch and another v Kommunale Wasserwerke Leipzig GmbH ("KWL") [2010] (English Commercial Court, London) and KWL v UBS AG and others (parallel proceedings before the German Landgericht Leipzig).

If Article 22.2 could apply to such claims, it might allocate "exclusive jurisdiction" to the "home Courts" of the entity in question notwithstanding any jurisdiction clause to the contrary. It might have this effect in light of:

- Article 23.5 - which provides that agreements conferring jurisdiction are to have no legal force if the Courts whose jurisdiction they purport to exclude have exclusive jurisdiction by Article 22; and

- Article 25 - which states that if a claim is "principally concerned" with a matter over which the Courts of a Member State have exclusive jurisdiction by virtue of Article 22, other Courts shall declare of their own motion that they have no jurisdiction.

THE DECISION :

The ECJ ruled that Article 22.2 does not apply to any such contractual proceedings. It thus gave Article 22.2 a narrow interpretation - apparently even narrower than that applied by the English Courts to date.

This emphatic decision has established a universally applicable point of principle which should finally put all arguments in this respect to bed. It has two crucial effects:

- It makes it easier to assess with greater certainty in which European countr(y's)(ies') Courts a claim of a contractual nature may legitimately be commenced.

- It should remove as a possibility the ability of a party to sidestep a jurisdiction agreement when (or indeed by) raising ultra vires or similar arguments in contractual claims.

The decision will come as very welcome news not only to financial institutions, but indeed to all entities doing business in Europe which seek to uphold the jurisdiction clauses in their commercial contracts.

Further details and analysis

THE SWAP CONTRACT

- JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A., a US investment bank ("JPM Chase"), and BVG, a German public law entity, entered into an Independent Collateral Enhancement Transaction involving a swap transaction (the "Swap Contract"). The Swap Contract contained a clause conferring jurisdiction on the English Courts.

THE ENGLISH PROCEEDINGS

- JPM Chase and its English subsidiary, J.P. Morgan Securities Ltd, (together "JPM") commenced proceedings in the Commercial Court in London for payment pursuant to the Swap Contract, and for various declarations that the Swap Contract had been entered into freely, without reliance on advice from JPM, and was valid and enforceable.

- BVG asserted that it did not have to pay since JPM had given poor advice. It subsequently also argued that the Swap Contract was not valid since BVG had acted ultra vires when the contract was concluded – and that thus the decisions of its organs leading to the conclusion of the Swap Contract were null and void.

THE GERMAN PROCEEDINGS

- Meanwhile, BVG commenced subsequent proceedings in the Berlin Regional Court (Landgericht Berlin) against JPM Chase. It sought a declaration that the Swap Contract was void because its subject matter was ultra vires given BVG's constitutional statutes, or in the alternative that JPM Chase should release BVG from its obligations, and pay it damages, by reason of JPM's incorrect advice.

THE COURTS ' RESPECTIVE APPROACHES TO THE PARALLEL PROCEEDINGS

- As the Court "first seised" pursuant to Article 30 of the Brussels I Regulation, the English Court first considered whether or not it could hear the dispute.

- In the interim, the Landgericht Berlin (as the Court "second seised" of proceedings involving the same "cause of action" and between the same parties) ordered a stay of its proceedings - pending the decision of the English Court on its ability to hear the claim. The stay was ordered pursuant to Article 27 – the mechanism designed to ensure that the Courts of two Member States would not reach conflicting decisions in respect of the same claim.

THE ENGLISH COURTS ' APPROACH TO JURISDICTION

- In the English proceedings, JPM asserted that the English Courts could hear the dispute under Article 23 of the Brussels I Regulation – i.e. because of the English jurisdiction clause in the Swap Contract.

- BVG, however, contested the jurisdiction of the English Court. It argued that the "object"/ "principal concern" of the proceedings was a matter subject to Article 22.2, namely the validity of the decision of it organs to enter into the Swap Contract. As such, it asserted, "exclusive jurisdiction" to hear the dispute was conferred on the German Courts, and the English Court was obliged, pursuant to Article 25, to declare of its own motion that it had no jurisdiction.

- The English Courts disagreed with BVG, and ruled that the English courts had juristiction. Both Teare J, and subsequently the Court of Appeal, considered that the "object"/"principal concern" of the proceedings was instead the validity of the Swap Contract and whether JPM could enforce its rights under it.

- This was, at least primarily, because BVG's likely defences comprised not only ultra vires, but also allegations that JPM failed properly to advise, made misrepresentations, failed to disclose relevant matters and otherwise was in breach of contract – thereby raising various other issues, such as how the Swap Agreement worked according to its terms and what was said at various meetings in that respect.

- The English Courts did not, however, directly rule on the question of whether, had the only basis on which the claim was defended been the ultra vires point, such contractual proceedings would invoke Articles 22.2 and 25.

THE GERMAN REFERENCE TO THE ECJ

- Back in Germany, BVG had appealed the Landgericht Berlin's

decision to stay the German proceedings, and that appeal had come

before the Kammergericht Berlin (the Higher Regional German Court).

Prior to the English Court of Appeal giving Judgment, in March 2010

the Kammergericht Berlin referred the following three Questions to

the ECJ:

"(1) Does the scope of Article 22(2) of Council Regulation (EC) No 44/2001 of 22 December 2000 on jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments in civil and commercial matters also extend to proceedings in which a company or legal person objects, with regard to a claim made against it stemming from a legal transaction, that decisions of its organs which led to the conclusion of the legal transaction are ineffective as a result of infringements of its statutes?

(2) If the question under (1) is answered in the affirmative, is Article 22(2) of Regulation No 44/2001 also applicable to legal persons governed by public law in so far as the effectiveness of the decisions of its organs are subject to review by civil courts?

(3) If the question under (2) is answered in the affirmative, is the court of the Member State last seised in legal proceedings required to stay the proceedings pursuant to Article 27 of Regulation No 44/2001 even if it is claimed that, as a result of a decision of the organs of one of the parties which is ineffective under its articles of association, an agreement conferring jurisdiction is likewise ineffective?"

- In essence, these Questions raised two points:

- First, did the scope of Article 22.2 extend to a claim of the nature in question – so as to allocate "exclusive jurisdiction" to the German Court?

- If so, could the German Court, as an exception to Article 27,

proceed to hear the claim notwithstanding being "second

seised"? This possibility was apparently advanced on two

bases:

- If the German Court had exclusive jurisdiction under Article 22.2, it should not be prevented from proceeding. This issue had previously been expressly left open by the ECJ in Overseas Union v Insurance Ltd v New Hampshire Insurance Co (Case C-351/89). In this respect, note that any English decision on the merits of the claim which was given in breach of Article 22 would be rendered unenforceable in other Member States pursuant to Article 35.1. This might be seen as supportive of an argument that the German Court should be allowed to proceed.

- The clause conferring jurisdiction on the English Courts was

contained with the very agreement which, it was alleged, was null

and void because of the invalidity of the decision to enter into

it, and it was alleged that the jurisdiction clause was itself also

null and void for the same reason.

THE ENGLISH REFERENCE TO THE ECJ

- Despite the reference made to the ECJ by the German Court, the English Court of Appeal had previously refused to grant permission to appeal or to make a reference itself to the ECJ.

- However, following the English Court of Appeal's dismissal of its appeal on jurisdiction, BVG made an application to the English Supreme Court for permission to appeal that decision. In light of the German reference (and possibly solely because of it), in December 2010 the English Supreme Court referred three Questions of its own to the ECJ.

- In reaching their judgments, both Teare J and the Court of Appeal had first formed an overall judgment of the particular proceedings before them before assessing the applicability of Article 22.2. They had not specifically questioned, as a point of principle, whether claims of a contractual nature involving ultra vires type defences could ever invoke Article 22.2. Indeed, as noted above, their decisions that Article 22.2 did not apply placed considerable reliance upon the existence of BVG's other assertions in the case at hand (such as the failure properly to advise, misrepresentations, failure to disclose relevant matters and other breaches of contract).

- The English Supreme Court adopted a similar approach. Thus, the questions it referred to the ECJ did not expressly ask whether Article 22.2 applied in claims of a contractual nature at all. Indeed, at the oral hearing, there was an apparent assumption/ acceptance that Article 22.2/25 could apply to such claims - and indeed would apply if the only issue in dispute in the claim was an ultra vires point.

- Instead, therefore, the focus of the English Supreme

Court's Questions was on the general approach and test to be

applied, on a case by case basis, when assessing whether the claim

was subject to Articles 22.2 and 25. In particular, they

asked:

- whether the claim alone was to be considered, or also the defences or other arguments to be advanced by the defendants;

- whether, if the "validity of decision of organs"

issue was potentially dispositive of the claim, that necessarily

made it the "object"/"principal concern" of the

proceedings - and, if not, whether a Court should assess what the

"object"/"principal concern" was by forming an

overall judgment of the proceedings as a whole, or by applying some

other test.

- The precise Questions referred by the English Supreme Court

were as follows:

"(1) When identifying, for the purposes of Articles 22(2) and 25 of the Council Regulation (EC) No. 44/2001 of 22 December 2000 on Jurisdiction and the Recognition and Enforcement of Judgements in Civil and Commercial Matter (the "Brussels I Regulation") what proceedings have as their object and with what they are principally concerned, should the national court only have regard to the claims made by the claimant(s) or should it also have regard to any defences or arguments raised by the defendants?

(2) If a party raises an issue in proceedings which falls within the subject matter of Article 22(2) of the Brussels I Regulation, such as an issue as to the validity of the decision of an organ of a company or other legal person, does it necessarily follow that that issue forms the object of the proceedings and that the proceedings are principally concerned with that issue if that issue may be potentially dispositive of the proceedings, irrespective of the nature and number of other issues raised in the proceedings and of whether all or some of those issues are also potentially dispositive?

(3) If the answer to question (2) above is negative, is the national court required, in order to identify the object of the proceedings and the issue with which the proceedings are principally concerned, to consider the proceedings overall and form an overall judgment of their object and what they are principally concerned with; and if not, what test should the national court apply to identify these matters?"

THE ECJ DECISION ON THE GERMAN REFERENCE

- Although the English Supreme Court had asked the ECJ to join its reference with that made by the German Kammergericht Berlin, the ECJ in fact heard the German reference on its own on 10 March 2011. It then also rendered its decision on 12 May 2011 - even before the English reference had been heard, and without the Advocate General first submitting a written opinion. It did so having considered submissions made not only by the parties, but also by the UK and Czech Governments, and the European Commission.

- Question (1) of the German reference, unlike the reference made by the English Supreme Court, raised expressly the question of whether Article 22.2 could apply to contractual proceedings in which a party asserted that the contract was void on ultra vires or similar grounds.

- The ECJ decided that the answer to Question (1) of the German reference was "no". It thereby established a universally applicable point of principle – that Article 22.2 did not apply to any such contractual proceedings. It did so in order that the jurisdictional rules could be applied with certainty and predictability, and thus construed Article 22.2 as having a narrow application, apparently even narrower than had been envisaged by the English Courts.

- The main reasons given by the ECJ for its decision were as

follows:

- Since Article 22 was an exception to the general rule, the ECJ had always adopted a strict interpretation of that provision - one no broader than that which its objective required. Although there were different language versions of the relevant provisions, they should be interpreted uniformly and taking account of the purpose and general scheme of the Brussels I Regulation.

- The primacy of Article 22 (by virtue of Article 23.5) particularly justified a strict interpretation because it afforded exclusive jurisdiction and, as such, its application would deny the parties to a contract all autonomy to choose another forum.

- A broad interpretation of Article 22.2, such that it applied to any proceedings in which a question concerning the validity of a decision of a company's organs was raised, would be contrary to one of the express aims of the Regulation – to attain jurisdictional rules which are highly predictable, and also to the principle of legal certainty.

- Predictability would also not be achieved if the applicability of Article 22.2 varied according to whether a preliminary issue as to the validity of the contract, which is capable of being raised at any time by one of the parties, existed.

- The aim of Article 22.2 was to confer exclusive jurisdiction on the Courts of the Member State in which a company has its seat in respect of disputes which related exclusively or principally to the validity of decisions of that company's organs. That was on the basis that such a Court was best placed to decide such disputes.

- However, in a dispute of a contractual nature, issues relating to the contract's validity, interpretation, or enforceability are what is at the heart of the dispute and form its subject matter. Any question concerning the validity of the decision to conclude the contract must be considered ancillary. While such a question may form part of the analysis, it does not constitute the sole or principal subject.

- Further, the subject-matter of such a contractual dispute does not necessarily display a particularly close link with the Member State in which the company in question has its seat. Thus, a broad interpretation of Article 22.2 would not be consistent with the objective of that provision. As a result, such contractual claims should not be subject to Article 22.2.

- The ECJ's narrow interpretation of Article 22.2 would not

lead to a risk of conflicting judgments - in light of the rules

concerning parallel proceedings (Article 27), and the obligation to

recognise and enforce the judgments of Courts of Member States (not

given in breach of Article 22) in all other Member States.

- In light of its decision on Question (1), the ECJ declined to

answer Questions (2) and (3) of the German reference. As a

consequence, two related key issues remain unanswered by the

ECJ:

- If a Court which is "second seised" of the relevant "cause of action" (between the same parties) considers that the proceedings are subject to Article 22, can that Court proceed to hear that claim, or (more likely) must it stay those proceedings pursuant to Article 27.1, and await the decision on jurisdiction of the Court "first seised"?

- If the Court "first seised" decides it can hear the

claim, must the Court "second seised" then decline

jurisdiction (pursuant to Article 27.2) even if it disagrees and

considers that it has "exclusive jurisdiction" under

Article 22 - and, on that basis, will not, in any event, enforce

the Judgment of the Court "first seised"?

IMPACT OF THE DECISION ON THE EXISTING PROCEEDINGS

- Following the ECJ's decision, it is anticipated that BVG's application for permission to appeal to the English Supreme Court will be dismissed and that the JPM v BVG claim, like many other similar claims, will now proceed in the Commercial Court in London.

- It is also anticipated that the German Courts will decline jurisdiction over their parallel BVG v JPM Chase proceedings.

CONCLUSION: IMPLICATIONS OF THE DECISION IN THE COMMERCIAL ARENA

- The ECJ decision is of considerable importance, not only for financial institutions, but for all entities conducting commercial business, in whatever sector, within Europe.

- It has two key effects:

- First, it makes it easier to assess with greater certainty in which European countr(y's)(ies') Courts a claim of a contractual nature may legitimately be commenced.

- Second, it prevents a party from claiming an entitlement to

have contractual disputes resolved in its home Court when (or

indeed by) raising ultra vires or similar arguments, and

thereby seeking to sidestep any jurisdiction agreement.

- As a consequence, the decision is very welcome news indeed for all those desirous of greater degree of legal certainty, including those eager to rely on the jurisdiction clauses contained in their commercial contracts with European counterparties.

Learn more about our Litigation & Dispute Resolution, Banking & Finance Litigation and Derivatives & Structured Products Practices.

Visit us at mayerbrown.com

Mayer Brown is a global legal services organization comprising legal practices that are separate entities (the Mayer Brown Practices). The Mayer Brown Practices are: Mayer Brown LLP, a limited liability partnership established in the United States; Mayer Brown International LLP, a limited liability partnership incorporated in England and Wales; Mayer Brown JSM, a Hong Kong partnership, and its associated entities in Asia; and Tauil & Chequer Advogados, a Brazilian law partnership with which Mayer Brown is associated. "Mayer Brown" and the Mayer Brown logo are the trademarks of the Mayer Brown Practices in their respective jurisdictions.

© Copyright 2011. The Mayer Brown Practices. All rights reserved.

This Mayer Brown article provides information and comments on legal issues and developments of interest. The foregoing is not a comprehensive treatment of the subject matter covered and is not intended to provide legal advice. Readers should seek specific legal advice before taking any action with respect to the matters discussed herein.