Executive Summary

In early October 2023, Oxfam put out a press release with the headline, "world's poorest countries to slash public spending by more than $220 billion in face of crushing debt." This headline has alarming implications for political stability, considering that austerity and unrest have been shown to have a strong correlation. In general, despite dramatic examples in Ecuador and Sri Lanka, austerity appeared to play a relatively small role in global protest in 2022 and 2023, when nearly 80% of countries either held government spending constant or increased expenditures. 2024 appears likely to be a different story, as governments struggle to manage unsustainable debts. The current emerging market debt crisis could be compounded by social unrest.

Looking at the mechanisms by which austerity links to unrest, we might expect the current emerging markets debt crisis to result in more countries opting for less transparent short-term funding; significant risks that debt sustainability initiatives will prove self-defeating; and an elevated chance of 'contagious protests' spreading to multiple countries. An Index of people power and pressure for spending cuts suggests that countries already in default will face the highest risk, although Brazil appears to have a surprising potential for austerity-linked unrest.

Introduction

This essay begins with a quiz. What do the following political events have in common?

- The 2011 collapse of the Egyptian government during the Arab Spring

- The 2018 gilets jaunes protests in France

- The 2019-20 riots in Chile

- The 2022 flight into exile of the president of Sri Lanka

One obvious answer might be that each incident involves mass political action. A less obvious answer would be that each incident involves policies of austerity (that is, net reductions in government spending, either through tax increases or spending cuts).

One trigger for the collapse of Sri Lanka's government – following decades of rapid economic growth – was that the government-subsidized fuel price was allowed to appreciate. In Chile, a trigger for months of protests was the effective reduction in government subsidies for public transport (and thus, famously, higher subway fares in Santiago). In France, one spark for protests was provided by a proposed increase in fuel taxes. In Egypt, Arab Spring unrest was augmented by public opposition, expressed on the streets, over a government decision to allow the subsidized price of bread to rise.

The relationship between austerity and public protest is a well-known one. (Had we added explicit anti-austerity protests to the above list, such as those in Argentina, Greece or, more recently, Ecuador and Lebanon, we would surely have given the game away.) And yet, on a statistical basis, the relationship between austerity and unrest has been relatively little researched (although excellent case studies are abundant).

That omission is surprising when one considers that efforts to create models to explain the timing of political instability have thus far had limited success. Over decades of research, many factors have been shown to correlate with state fragility. For instance, anocracies (states in which power is contested but not via free and fair elections) appear to be more likely than either democracies or dictatorships to experience violent turmoil; countries with large natural resource exports appear to have longer, and perhaps more frequent, civil wars. Predicting the timing of instability appears to be more of a challenge, though, with efforts focusing on artificial intelligence early warning systems.

Austerity, however, has already been indicated to correlate with the timing of unrest, using relatively simple statistical approaches. In the next section, we will review this research and offer an update based on ACLED data.* We will then consider why austerity correlates with unrest, and look at some of the links between austerity and unrest provided by the Oxford Analytica contributors who authored profiles in this edition of the Willis Political Risk Index.

In early October 2023, Oxfam put out a press release with the headline, "world's poorest countries to slash public spending by more than $220 billion in face of crushing debt."Now seems an appropriate time to dig into the topic of austerity and unrest. This essay will conclude with an index of countries most at risk in 2024.

Austerity and unrest by the numbers

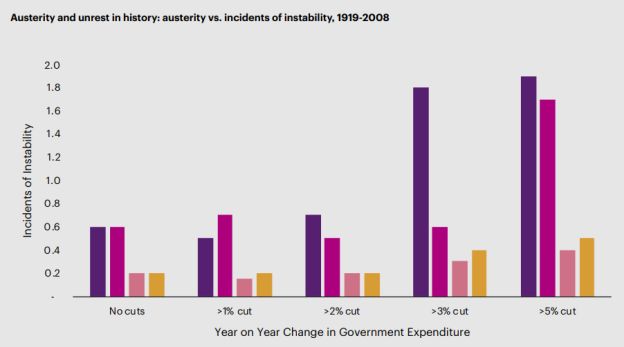

One of the most comprehensive statistical studies of the relationship between austerity and unrest was published about a decade ago by Hans-Joachim Voth and Jacopo Ponticelli. In that study on Europe, and then in a subsequent piece on Latin America, the authors looked at a long time horizon and found a strong statistical relationship between spending cuts and the incidence of social unrest. In Latin America, there was a further relationship between austerity and military coups (the relationships for Europe are shown in the graph above).

In more recent years, there have been numerous studies of a special case of this phenomenon – the link between removal of subsidies on food or energy and social unrest. The link between these two areas of research is not perfect; in countries that are food or energy producers, price controls can have a similar political effect as explicit fiscal transfers. (Indeed, in many protests in the ACLED database demonstrators will demand that the government "fix prices" without specifying a mechanism.) This special case was addressed in the last edition of the Political Risk Index, which looked at cost of living crises.

Source: "Austerity and Anarchy: Budget Cuts and Social Unrest in Europe, 1919-2008," by Jacopo Ponticelli and Hans-Joachim Voth (2011); see also "Tightening Tensions: Fiscal Policy and Civil Unrest in Eleven South American Countries, 1937-1995" by Hans-Joachim Voth (2012)

One of the most comprehensive statistical studies of the relationship between austerity and unrest was published about a decade ago by Hans-Joachim Voth and Jacopo Ponticelli. In that study on Europe, and then in a subsequent piece on Latin America, the authors looked at a long time horizon and found a strong statistical relationship between spending cuts and the incidence of social unrest. In Latin America, there was a further relationship between austerity and military coups (the relationships for Europe are shown in the graph above).

In more recent years, there have been numerous studies of a special case of this phenomenon – the link between removal of subsidies on food or energy and social unrest. The link between these two areas of research is not perfect; in countries that are food or energy producers, price controls can have a similar political effect as explicit fiscal transfers. (Indeed, in many protests in the ACLED database demonstrators will demand that the government "fix prices" without specifying a mechanism.) This special case was addressed in the last edition of the Political Risk Index, which looked at cost of living crises.

To view the full article, click here.

Footnote

*ACLED provides day-by-day, geocoded political event data drawing on media sources, and has compiled records of more than a million events already

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.