Overview

The Government's proposed statutory test for UK tax residence, intended to be effective from 6 April 2012, was published on 17 June 2011 and is to be welcomed. It is much clearer than the current unsatisfactory system for determining UK tax residence. Moreover it should allow some non-UK residents a degree of additional flexibility in managing their visits to the UK.

We believe that there is scope for improving the proposals to give greater clarity in certain areas and we will be making representations to the Government as part of the consultation process (which ends on 9 September 2011).

The new statutory residence test

The proposed test falls into three parts as set out below.

Part A: an individual will be conclusively non-UK resident in a particular tax year1 if

- he has been non-UK resident in each of the previous three tax years and he is present in the UK for fewer than 45 days in the tax year in question; or

- he was resident in the UK in one or more of the previous three tax years and he was present in the UK for fewer than ten days in the tax year in question; or

- he leaves the UK to carry out full-time work abroad, is present in the UK for fewer than 90 days in the tax year and works for no more than 20 days in the UK in the tax year in question. (A working day requires at least three hours or more of work; an individual claiming to have worked for under three hours a day may be required to retain evidence of this.)

If, and only if, a person does not satisfy any of the conditions in Part A (so as to be conclusively non-UK resident), then go to Part B.

Part B: an individual will be conclusively UK resident in a particular tax year if

- he is present in the UK for 183 days or more in the tax year;

- his only home or homes are in the UK (but ignore a home that is for sale or which is let with the individual living elsewhere); or

- he carries out full-time work in the UK ("full-time" means at least 35 hours per week for a continuous period of more than nine months - ignoring short breaks – with no more than 25% of duties outside the UK during that period).

If an individual does not satisfy the conditions in Part A (so as to be conclusively non-UK resident) or in Part B (so as to be conclusively UK resident), then go to Part C.

Part C: in order to determine UK residence status the individual must consider (a) how many of the specified "connecting factors" apply to him and (b) how many days he spends in the UK in the tax year in question.

The greater the number of connecting factors that apply to the individual, the fewer the number of days he is permitted to be present in the UK without becoming UK resident. Individuals are to be categorised as either "arrivers" or "leavers" by reference to whether or not they have been UK resident in any of the three tax years immediately preceding the tax year in question. It is a deliberate aim of these rules to make it more difficult to be non-UK resident as a "leaver" than as an "arriver".

One potential difficulty is that it is presently proposed that in categorising an individual as an "arriver" or a "leaver", residence for all tax years prior to 2012/13 will be assessed under the "old" rules – under which it may not be possible to say with certainty whether or not an individual is UK resident. Unless some kind of transitional rule is introduced following consultation, in cases of doubt it may be sensible for individuals who wish to remain non-UK resident to regard themselves as "leavers" until 2015/16, when they will have had the opportunity to accumulate three years of hopefully certain non-UK residence under the statutory residence test.

If a person is an "arriver" (having been non-UK resident in each of the three tax years preceding the tax year in question) the connecting factors that have to be taken into account are:

- having a UK resident family

- having accessible accommodation in the UK

- having substantive UK employment (including self-employment) for at least 40 days in the tax year; to count, a day must involve more than three hours of work

- spending 90 days or more in the UK in either of the two previous tax years

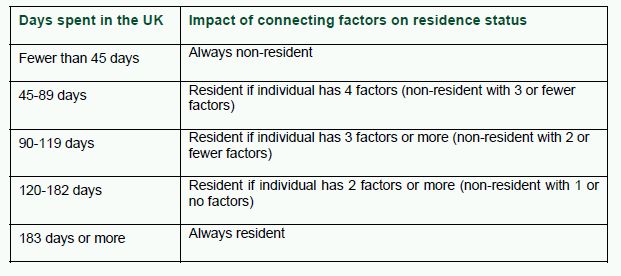

For "arrivers" the connecting factors tie in with the number of days spent in the UK as set out in the table below.

Note that the day counting is undertaken by reference only to the tax year in question. There is no concept of considering an average annual number of days in the UK, as happens in certain circumstances at present.

If a person is a "leaver" (having been UK resident in one or more of the previous three tax years) the relevant connecting factors are:

- having a UK resident family

- having accessible accommodation in the UK

- having substantive UK employment (including self-employment) for at least 40 days in the tax year

- spending 90 days or more in the UK in either of the two previous tax years

- spending more time in the UK than in any other single country

Some of these terms are explained in more detail in the "Background" section below.

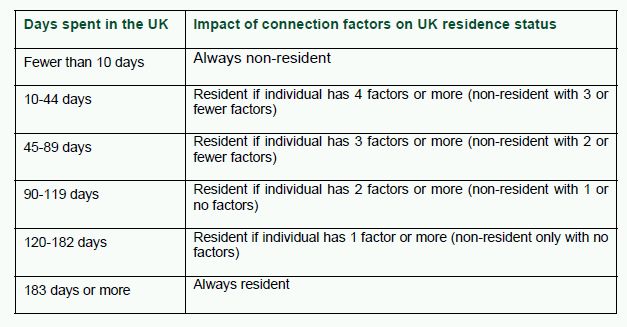

For "leavers" the connecting factors are combined with days spent in the UK to determine residence status as follows.

Background

Current rules on residence

At the moment, unless a person spends 183 days or more in the UK per tax year (when he will definitely be UK resident) a more or less open-ended range of factors is relevant to his UK residence status. These factors include the location of the individual's close family members, his home, his business connections and his social connections, the purpose of visits made to the UK and his nationality, to mention only some of the more obvious factors. HMRC's guidance contained in a document known as HMRC6 (which replaced an earlier document called IR20) is heavily caveated so that in practice in many cases it cannot be relied upon. There are particularly great difficulties in successfully becoming non-UK resident, other than in a limited range of circumstances. It is because of the uncertainty created by these rules that over many years solicitors and other tax advisers have been calling for a statutory residence test in order that people leaving and arriving in the UK may do so with confidence as to the effect on their UK residence status.

Proposed new rules on residence: some definitions

Days of presence in the UK. Under Parts A, B and C of the proposed new statutory residence test, it is necessary to determine the individual's days of presence in the UK. Here the existing rule applies for determining what amounts to a day spent in the UK. Thus, a person will be treated as being in the UK on any day when he is in the UK at midnight at the end of the day. The exception for persons transiting through the UK who are present here at the end of the day but do not undertake activities such as a business meeting substantially unrelated to their transit will continue to apply under the new rules. There does not appear to be any ability to ignore days spent in the UK owing to "exceptional circumstances" (for example an illness which prevents an individual from travelling), as applies in certain circumstances at present.

Family. One of the Part C connecting factors applies if the individual in question has a UK resident family. In this context the connecting factor applies if the individual's spouse, civil partner or common law equivalent are resident in the UK or any part of it (but ignore a spouse, civil partner or common law equivalent if the individual in question is separated under a court order or separation agreement or where the separation is likely to be permanent) or if the individual's children under 18 are resident in the UK and the individual spends time with them or lives with them for all or part of 60 days or more during the tax year. However, a child will not be treated as UK resident if their UK residence is mainly caused by them being at boarding school in the UK; this will be the case when the child spends under 60 days in the UK outside school and his/her main home is not in the UK.

Accommodation. A further Part C connecting factor relates to the individual having accommodation in the UK. This must be accommodation that is accessible and the individual must use it during the tax year (there are exclusions for some types of accommodation including hotels, staying with relatives on a temporary basis or non-consecutive leases of six months or less).

Other aspects of the proposed statutory residence test

Split years

The basic principle at present is that a person is either resident in the UK for a full tax year or non-resident for a full tax year. By concession, however, a tax year can be split so that a person is treated as UK resident for only part of a tax year. This will be the case if:

- he comes to the UK to take up permanent residence; or

- he leaves the UK to take up permanent residence abroad; or

- he loses his UK residence when leaving to work full-time outside the UK.

The proposed new rules also incorporate a split year test but it does not exactly replicate the previous one which relied upon the rather vague concept of a person becoming "permanently" resident in the UK or elsewhere. Instead under the new rules a tax year will be split into periods of residence and non-residence if the individual in question

- becomes resident in the UK by reason of having their only home in the UK;

- becomes resident by starting full time employment in the UK;

- establishes his only home in a country outside the UK, becomes tax resident in that country and does not come back to the UK in that tax year;

- loses UK residence by virtue of working full time abroad; or

- returns to the UK following a period of working full time abroad.

However, a tax year will not be split if an individual's residence status changes due to a change in the number of connecting factors which apply to him under Part C, such as the arrival or departure of his family. (If a person is non-UK resident for only part of a tax year under the split year rule then the 20 day and 90 day tests in Part A are reduced pro rata. Moreover a working day requires at least three hours or more of work; someone claiming to have worked for under three hours a day may be required to retain evidence of this.)

Anti-avoidance provisions

Ceasing to be UK resident means that an individual is no longer liable to UK tax on income from non-UK sources. This means that those who want to avoid liability on substantial amounts of income could plan short periods of temporary non-residence to achieve that. The new rules will therefore contain provisions to counteract the risk of individuals creating artificial, short periods of non-residence during which they receive free of tax large amounts of income which have accrued during periods of UK residence.

The proposed statutory residence test will contain rules that will work in a manner similar to the existing anti-avoidance rules for capital gains tax. These apply where an individual has been resident in four of the seven tax years prior to the tax year in which they became non-resident; and then becomes resident again in any of the following five tax years. In that case, subject to some exceptions, chargeable gains and allowable losses that arose during the years of non-residence are treated as arising instead in the tax year in which the individual becomes UK resident again. They will thus be taxable as if the person had been UK resident throughout.

Ordinary residence

Ordinary residence is a different concept from residence. As with residence, there is no statutory definition at the moment.

Ordinary residence is relevant to a person's tax liability in certain ways, including:

- A person who is not ordinarily UK resident can claim the remittance basis of taxation for foreign investment income. This means they are only liable to UK tax on such income if, broadly speaking, it comes into the UK; and

- If non-ordinarily resident, a person is entitled to the remittance basis on income from foreign employment duties where the income is paid by a UK employer and hence is a UK source (known as "overseas workday relief"). This is particularly important for short-term secondees to the UK.

One of the questions open for consultation is whether the concept of ordinary residence should be retained generally or only for the purposes of overseas workday relief.

Under the Government's proposed definition individuals who are resident in the UK will also be treated as ordinarily resident unless they have been non-UK resident for all of the previous five tax years. If they have been non-UK resident for the previous five tax years, they might not be ordinarily resident unless their only home or homes are in the UK. The status of being non-UK ordinarily resident should be available for a maximum of two years following the end of the year of arrival.

Conclusion

The proposed statutory test is a distinct improvement upon the current complex rules for determining a person's UK residence status. The document published on 17 June 2011 is for consultation purposes and so the principles set out there could be changed in the course of the consultation and Parliamentary process. Nevertheless the outlines of the proposals are clear, and seem to be workable and logical. For example, if the test is enacted in the form set out in the consultation document, a person would be able to come into the UK for at least ten days without having to worry that he will become UK resident. Currently this clarity does not exist. And more generally, the statutory test, as we had hoped, appears to provide relatively clear cut tests for residence. It is to be hoped that this clarity is retained during the course of the consultation process and scrutiny by Parliament.

Footnote

1 A tax year rums from 6 April in one year to 5 April in the following year.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.