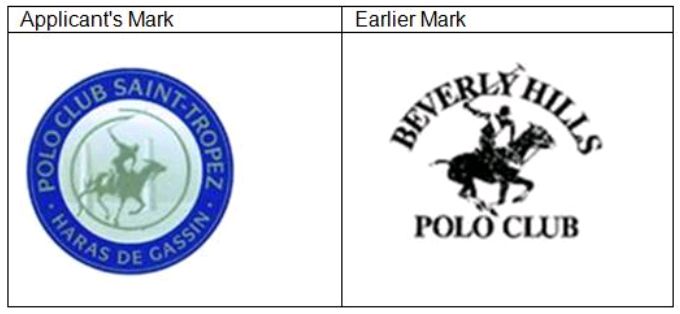

The US-based Beverly Hills Polo Club ("BHPC") fashion brand has successfully opposed the EUTM application of the French polo club, Polo Club Saint-Tropez ("Polo Club"), for its logo (above left) below at the EU General Court, on the basis that there was a likelihood of confusion with its earlier logo (above right). On its face, the Court's decision may surprise some, in view of the differences between the logos (in particular, the different geographical indicators "Beverly Hills" and "Saint-Tropez) and their arguably generic polo-related word and figurative elements. However, it also rides on the back of a series of similar successful EU oppositions by BHPC (and separate successful oppositions by another "polo" brand, Ralph Lauren) against various parties over the past years.

Polo Club's EUTM application was filed for the following goods and services:

- class 3: soaps; perfumes, perfumery; essential oils, cosmetics, hair lotions; dentifrices;

- class 41: training, education, entertainment; arranging and conducting of conferences, colloquiums, workshops, congresses, seminars, competitions (education or entertainment); production of films and video-tape films, radio programmes, radio and television entertainment, editing of video tapes, radio and television programmes, organisation of exhibitions for cultural or educational purposes, cultural activities, organisation of shows (impresario services); publication of books and texts (not including publicity texts).

BHPC opposed the EUTM application based on a likelihood of confusion with various of its earlier EUTM registrations for its logo, covering the goods and services below:

- class 3: soaps, perfumery, essential oils, cosmetics, lotions, creams, gels, powders, lipsticks, deodorants and antiperspirants, expressly excluding toothpaste, mouthwash and products for oral and dental care and hygiene;

- class 41: education; providing of training; entertainment; sporting and cultural activities.

BHPC also claimed enhanced distinctive character of those earlier marks, by producing some evidence within the deadline for submitting its arguments and evidence, and then by producing additional evidence in response to Polo Club's subsequent proof of use request, within the deadline for responding to that request.

The Opposition Division rejected the opposition, on the grounds that the initial evidence produced was insufficient to demonstrate that the earlier marks had enhanced distinctive character, and that the additional evidence was inadmissible because it had been submitted after the initial deadline. In the absence of enhanced distinctive character, it held the marks were insufficiently similar to find a likelihood of confusion, even if the goods and services were identical. The Fifth Board of Appeal annulled the Opposition Division's decision, and the General Court then upheld the Board of Appeal's decision, on the following grounds in particular:

- The relevant public for the goods and services in question was the general public. The overall likelihood of confusion had to be assessed from its perspective, with a normal level of attention.

- It was not challenged that the goods covered by the marks in class 3 were identical. The Court also found that the class 41 services "training, education, entertainment and cultural activities" were identically covered by Polo Club's EUTM and BHPC's earlier marks, and that the following respective services were also identical: "organisation of exhibitions for cultural purposes" and "cultural activities"; "arranging and conducting of conferences, colloquiums, workshops, congresses, seminars, competitions (education), organisation of exhibitions for educational purposes" and "cultural activities, education, providing of training"; "competitions (entertainment), organisation of shows (impresario services)" and "entertainment"; "production of films and videotape films, radio programmes, radio and television entertainment, editing of video tapes, radio and television programmes" and "entertainment, cultural activities". The Court also held that the services "publication of books and texts (not including publicity texts)" were similar to the services "education, providing of training", on the grounds that it is not unusual for educational centres (notably universities) to have their own publishing house, and those services are complementary and aimed at the same users.

- Applying previous EU Court decisions (involving separate successful oppositions brought by BHPC and Ralph Lauren), the Court held that the image of a polo player and the words "Polo Club" have no connection with, and have "high imaginative content and are intrinsically highly distinctive" in relation to, the class 3 goods. Further, those elements have "normal" inherent distinctiveness in relation to the relevant class 41 services, which do not relate specifically to polo.

- The Court found that the marks were visually and phonetically similar to a low degree, and they had at least an average degree of conceptual similarity.

- Based on all the factors above, the Court concluded that there was a global likelihood of confusion between the marks.

- Finally, the Court went on to hold that the Opposition Division should also have admitted BHPC's additional evidence of enhanced distinctive character. Applying previous case-law, the Court confirmed that, under article 76(2) of the EUTM Regulation – which relates to general time limits for submitting evidence – the EUIPO has a "broad discretion" whether to take into account evidence submitted after the expiry of a deadline. The Court also held that rule 20(1) of the EUTM Implementing Regulation – which relates to the deadline for proving "the existence, validity and scope of protection" of earlier marks – refers in particular to the definition of the goods and services protected by the earlier marks, not the greater or lesser extent of their distinctive character. In any event, BHPC had filed initial evidence of the "highly distinctive" character of the earlier marks within the initial deadline, and the additional evidence was complementary to that initial relevant evidence. Applying previous case-law, since Polo Club had disputed the initial evidence, BHPC had been entitled to submit the additional evidence. Further, the additional evidence was genuinely relevant, and had not been submitted at a very late stage of the proceedings, but in reply to the request for proof of genuine use. It would have been "artificial and over formalistic" only to admit that evidence for the purpose of showing genuine use of the earlier marks, but to ignore it for the purpose of assessing their distinctive character.

Case T-67/15

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.