Introduction

Following its victory in the High Court (see our article here), Marks & Spencer ('M&S') has emerged triumphant against Aldi in the latter's appeal to the Court of Appeal.1 The case, centred around the design of M&S's festive 'light-up gin bottles,' is a rare win for supermarkets in the domain of 'copycat' disputes, and also carries implications for registered design owners engaged in the ongoing struggle against imitation products. This victory provides hope to those safeguarding their intellectual property and serves as a potent warning to discount retailers not to sail too close to the wind.

The disputed designs: A festive elixir

At the core of this dispute are UK registered designs protecting M&S's Christmas product line introduced in the autumn of 2020. These distinctive gin-based flavoured liqueurs are presented in elegantly decorated bottles, featuring edible gold flakes that produce a snow globe effect when shaken. Adding a touch of innovation, the bottles are equipped with a light-emitting diode ('LED') at their base, illuminating both the contents and the suspended gold flakes. Aldi entered the market in November 2021, launching a competing product which sparked the legal showdown.

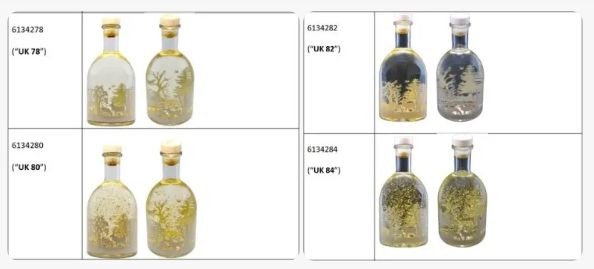

Marks & Spencer's registered designs are as follows:

Aldi's products are below:

Legal arguments and the court's verdict

Aldi, dissatisfied with the High Court's initial ruling, challenged the decision on a number of technical grounds (discussed below) and on two general grounds: In the first general ground, it argued that the court had not adequately considered the absence of certain features, such as the snow effect and integrated light, in their products. In the second main ground, Aldi contended that undue weight had been placed on the shapes of the bottles and stoppers, despite the bottle shape being disclosed by a third-party registered design and thus forming part of the design corpus.2 Lord Justice Arnold, who led the judgment of the court, dismissed these arguments, highlighting the judge's prerogative in assessing the overall impressions of the products. The Court of Appeal upheld the High Court decision, affirming Aldi's infringement of M&S's design rights. As Arnold L.J. said:

"[The Judge] made no error of principle in comparing the overall impressions of the Aldi products with those of the Registered Designs, and his conclusion was one that he was fully entitled to reach.".3

Features of the Registered Design

The Court had to determine whether some of the registered designs included the LED light feature. As a matter of general law, the Court of Appeal held that:

- The Court could look at the actual product (i.e. the M&S marketed product) rather than just the images included with the registered design.4 The Court followed the ruling of the CJEU in Pepsi v Grupo Promer Mon Graphic,5 in which the CJEU found that it is permissible to use the marketed products "to confirm the conclusions already drawn"6 from the designs.

- The Court could consider the indication of product (i.e. a description of the produce which is included with the registered design – in this case 'light up gin bottle') to resolve ambiguity.7 This is interesting because Rule 5(5) of the Registered Designs Rules 2006 provides that the indication of product shall not affect the scope of the protection. However, the Court reasoned that, if a third party is searching the register for designs of bottles incorporating a light, that party may be uncertain purely from inspecting the accompanying images as to whether the images depict such a light. If so, the statement that the product to which the designs are intended to be applied is a 'light up gin bottle' provides an unambiguous answer to the question and can therefore assist in the interpretation of the design.

Grace Period

It is well established that, when considering the validity of a registered design, designs disclosed by the registered design owner for the 12-months prior to the priority date for the registered design are not taken into account for the purposes of considering the validity of the registered design. In this case, the Court of Appeal had to decide a number of points with regard to this grace period, and in particular whether disclosures by the designer in the grace period could nevertheless affect the scope of protection of the design. This led to the following findings:

- The grace period also applies to assessing infringement. This means that, subject to point 2. below, a disclosure by the designer (or successor in title) in the grace period does not form part of the design corpus and thus does not have a narrowing effect on the scope of protection. The scope of protection of a registered design depends on how novel that design is within the existing similar designs (the 'design corpus'). The fewer similar designs there are, the broader the protection that it granted by the registered design;8 and

- The Court of Appeal discussed three interpretations of the grace period provision. In particular, the Court had to consider how similar a prior disclosure by the designer in the grace period needed to be in relation to the current registered design in order to not form part of the design corpus (being included in such would potentially limit the scope of the designs). The question was whether the provision covers: (1) disclosures by the designer in the grace period that are exact or differ only in immaterial details to the registered design; (2) any disclosure by the designer in the grace period that produces the same overall impression as the registered design; or, (3) any disclosure by designer in the grace period whatsoever. The Court of Appeal held that the middle ground is correct approach – this means that disclosures by a designer (or their successor in title) in the grace period that produce the same overall impression as the registered design are not part of design corpus, and any other disclosures are included. Arnold L.J. stated that:

"If designers test market a number of distinct designs, but only decide to register one, then they must accept the risk that the other designs may in some cases affect the scope of protection of the registered design."9

This means that disclosures in the grace period that produce a different overall impression from the registered design are part of design corpus and could thus narrow the scope of protection. Designers need to be very wary of this when publicly disclosing designs prior to filing the registered design application. The safest strategy remains to file first, and then disclose the filed design.

Date of Overall Impression

The Court of Appeal confirmed that the overall impression of the registered design is assessed for validity and infringement purposes at the priority date, not at the filing date (which in this case is many months later).10

Significance of the judgment

This judgment is significant, not just for M&S, but for all entities grappling with the challenge of protecting their designs against imitations. The outcome draws a sharp contrast with Thatchers' unsuccessful trade mark infringement case against Aldi (see our article on this here), further highlighting the importance of applying for registered design protection.

Implications for registered design owners

The Court of Appeal's decision is anticipated to empower registered design owners, providing a legal precedent and encouraging them to pursue enforcement actions against 'lookalike' products. Cost-effectiveness, speed, and simplicity of obtaining registered designs, position them as a desirable form of protection. This ruling clarified that variants disclosed within the one-year grace period do not constitute 'prior art', preserving the utility of the grace period for design exploration. Brand owners may wish to fortify their defences against imitations by creating a 'thicket' of registered rights, combining designs and trademarks.

Conclusion

Marks & Spencer's victory over Aldi sets a precedent for registered design owners, offering clarity and encouragement in their pursuit of justice against 'lookalike' products. Design rights remain a fast and cost-effective form of protection, and the decision is anticipated to empower registered design owners, encouraging enforcement actions against 'lookalike' products.

The decision not only underscores the strategic importance of registered designs in safeguarding intellectual property but also signals a potential shift in the landscape of intellectual property disputes, particularly within the competitive realm of FMCGs in supermarkets. As brand owners navigate this terrain, the ruling provides valuable insights into effective strategies for protecting designs against imitation, ensuring the continued innovation and distinctiveness of products in the market. However, given the Court of Appeal's findings with regard to the grace period and the design corpus, designers would be advised not to rely on the grace period where possible, and instead file for a registered design prior to disclosure of the design.

Footnotes

1. Marks & Spencer PLC v Aldi Stores Limited [2024] EWCA Civ 178

2. Ibid. at 62.

3. Ibid. at 63.

4. Ibid. at 17.

5. PepsiCo Inc v Grupo Promer Mon Graphic SA (C-281/10)

6. Ibid. at 74.

7. Above n. 1 at 18 et seq.

8. Above n. 1 at 46.

9. Above n. 1. at 53.

10. Above n. 1 at 58.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.