Forward

The downturn and long-term structural changes brought about by online media consumption have helped create unprecedented operational, organisational and financial challenges for the media industry.

In this context Deloitte and Spencer Stuart interviewed business leaders at the forefront of digital media across the UK landscape to understand the challenges around implementing digital strategies.

We will publish a series of papers focused on the key themes resulting from these interviews. Our first paper focuses on the challenge that media business leaders are facing as they look to resize and reshape their organisations in the face of the impact of both the downturn and the ever quickening digital transformation.

Executive summary

The dawn of a new decade has been accompanied by a period of significant challenge for media organisations. The recession has eaten into already shrinking revenues, this has been coupled with ever increasing pressure from digital business models which continue to challenge the status-quo. Leaders of media organisations have a choice about how they react to these challenges.

To date, many have acted defensively, cutting costs by shedding marginal headcount or applying a uniform percentage reduction. This has, in some cases, resulted in the loss of core skills and pre-empted a yet poorer performance. This approach can be likened to a cabbage soup diet: it delivers short term gains, is none too pleasant and there is a good chance that the weight will creep back on as soon as the normal diet is resumed, as fundamental problems have not been addressed.

As readers will recognise, getting healthy is not just about losing weight. It is also about building strength, improving flexibility and making lifestyle changes which enable us to maintain the fitness we've achieved.

Media companies should think strategically about their long term health – intelligently addressing issues around the size of their organisations and avoiding, at all costs, the destruction of creative and operational muscle under the indiscriminate cover of 'weight loss'.

The role of many organisations in the media industry is changing. For example, content delivery is increasingly becoming direct, as well as via traditional distributors. In some cases, this implies the cessation or merger of organisations; in others, outsourcing previously 'core' services.

In this context, media leaders will face significant pressures on:

- Revenue, with many already working to significantly reduced budgets.

- Organisational strategy, particularly leading to mergers and restructuring.

- Existing products/services and capabilities.

- The capability of their staff to respond to such changes.

This paper explores some of the new realities of reshaping organisations. The emerging reality involves a greater radicalism in both intended organisational outcomes and the leadership required to get there. There are numerous examples of reshaping that have already succeeded in the media industry. As an illustration, four success stories are highlighted in the final section.

The evolving nature of digital technology will continue to drive change in demand and supply choices within the UK Media sector. Its leaders can choose merely to react to reduced revenue and forced restructuring, or identify proactively how their organisations can learn to adapt to new shapes and sizes; protecting the profitability of existing products and taking their share of the emerging digital marketplace.

Doing nothing is not an option

2009 – nadir or new paradigm for UK media?

2009 was an annus horriblis for much of the UK media sector. In the creative sector, the recession triggered a sharp decline in advertising revenue that1 hit national and regional newspapers and magazines. The downturn also increased the long-term structural pressure that digital business models have been exerting on the industry over the past decade.

Many listed media companies suffered severe declines in revenues (see Figure 1), compounded by poor credit availability to threaten the existence of some of the UK's oldest media names. Deal activity in the UK media sector also declined by 36 percent year-on-year to the lowest levels since the dotcom bust.2 This, despite the plethora of distressed assets on offer.

As a result, many jobs have already been lost, with household names across the media industry shedding heads over the course of 2009 – 2010.

They might not want to pay for it. But consumers want more content, more of the time

Consumption trends offer good and bad news for the media sector. Newspaper circulation was almost universally down year-on-year3 but TV viewing climbed 5 percent in the first half of the year4 and the reach of radio remained stable despite the growing range of online options.

Online channels have enjoyed strong growth in demand, although revenue growth has not kept pace. Newspapers' websites almost all recorded double-digit increases in unique users in 2009.5 Whilst on-line consumption is still a tiny proportion of total consumption it is a swiftly growing channel for users of content.

These raw statistics, not to mention the success, (in usage, if not in cash generation terms) of new media organisations such as Spotify, Twitter and Youtube, demonstrate that consumers' access to more personal, individually-tuned channels is fuelling a fast rise in consumption, albeit from a low base. The growing penetration of smart phones7 and advent of next generation mobile data networks suggests that there will be no cessation of this demand for the foreseeable future. Even so, the new economics of the Internet suggest that competition for the consumer's attention will intensify and media organisations will have to run ever harder to keep up.

"We have more routes to market than ever before, we can have a direct relationship with our consumers. All of this is great – but there is more complexity than we have ever faced, and we need to build a new set of capabilities across our organisation."

John Robson, Head of Digital, Paramount.

The need to deliver more with less

The net result is that media leaders now need to achieve better quality, greater reach and right-first time business model innovation with significantly tighter budgets. As one executive commented:

"... we can no longer take chances with billion pound bets. Money is tight, we have to make sure we get our bets right."

Mike McMillan, International HRD, Paramount.

In order to succeed, management's ability to assess priorities, manage transitions and evaluate return on assets of often conflicting business initiatives will be paramount. A key executive responsibility will be the ability to undertake critical, non-sentimental, forwardlooking reviews of strategic direction that may well imply reshaping traditional business models and organisational structures.

As Carolyn McCall, formerly Chief Executive at GMG, observed:

"... it's not just to do with advertising and those more traditional ways of getting money – there will be many other ways of doing this and they might not even be online. It might be to do with expanding brands in ways we've never thought about and that requires completely different skills and thinking to what most of us know as media organisations."

Hitherto, most cost reduction initiatives have focused on 'cost-out quick', characterised by approaches such as: de-layering, merging back office functions and across-the-board fixed percentage cost reductions. While these savings will remain important, they will not suffice given the ongoing scale of change in the media marketplace. Critically, management risks customer service failure, brand leakage and an inability to see or exploit new markets and products. Furthermore, by focusing on short-term savings companies may forego the opportunity to undertake more radical reshaping and associated long-term gains.

With decreasing revenues from traditional products and a proliferation of new consumption options we believe that many traditional media companies will have to evolve further than they have done to date.

Many of the changes we have observed have involved reducing an organisation's size to keep it commercially viable. But organisations need to change shape as well as size.

Malcolm Wall, Virgin Media's former Chief Executive of Content explained:

"Shareholders are forcing management energy to focus on stripping out cost and implementing promotions to maintain earnings per share. This has major impacts for any organisation looking to develop a digital business."

Organisations need to be in shape such that they can take advantage of the opportunities that digital transformation offers while avoiding its inevitable curve balls. Organisations need to embed the flexibility necessary to respond to future challenges.

Leaders should ask themselves:

- Is this organisation in the right shape to deliver services/products in the different ways that will be required?

- Do we know where to invest when resources are scarce?

- Have we got the right number of people, in the right place doing the right things, in this organisation?

Myths and new realities

The digital transformation challenges many enduring myths in the Media world. As leaders look to reshape their organisations for the long term they will have to overcome these myths and create new realities.

As the myths and realities that we have laid out in the table above demonstrate the challenge the media sector faces should not be underestimated. This is the first time since the Great Depression that such deep and wholesale cuts have been made to the operating bases of so many parts of the industry. The ramifications of this loss in creative and operational talent are as yet unknown but could be felt for years to come.

The financial crisis and the surge of business model innovation from the online world have combined to reshape the UK media industry. Media business leaders now face the seemingly contradictory challenge of satisfying shareholders hungry to strip out costs and maintain EPS whilst investing in and developing a new digital proposition.

Changes needed to structure

Redundancies have been necessary to enable the short-term survival of the UK's media enterprises. The new challenge for these slimmed-down enterprises is avoidance of a long, slow starvation. The structural issues that existed before the downturn are even more pronounced today.

The downturn in advertising, for example, has adversely impacted online spend, but less so than traditional channels, leading to online's share of ad spending growing 4 percentage points to 23 percent in 2009.8 The previous examples of iPlayer and newspaper websites only drive home the point that structural consumption trends are accelerating as consumers are able to be more selective with their consumption and moribund business models struggle.

The structural questions this raises are difficult ones. Should "online" be a business unit in its own right or at the centre of the business? Should content creation be super-ordinate to distribution channels or vice versa? Will the monetisation models that have sustained a business for decades work in the new economy?

"Digital media touches every part of the broader DMGT business today, yet we are still wrestling with the organisation structure question – very much a work in progress."

Richard Titus, CEO Associated Northcliffe Digital.

The answer varies but what is certain is that slimmer versions of old businesses will only survive a little longer than their heavier progenitors; a short-term focus on cost reduction programmes may simply divert investment away from potential growth areas and alternative revenue sources. To thrive in the new environment businesses need to become lean and need to consider how they will look different in order to best exploit new digital opportunities.

Changes needed in resourcing

Just as an enterprise's structure must adapt to the new requirements of a multi-dimensional competitive landscape, so must its human and technical resources. The fallacy of promoting old-media experts into newmedia roles has been cruelly and brutally exposed by the fast-thinking raiders from companies such as Google, Apple, and Amazon. There have been isolated successes, such as FT.com, but many of the strategic decisions of the old-media establishment have been poor, leading to ever more strategic control points being conceded to their young challengers.

The knack, it seems, is to find leaders that are neither oblivious to nor overexcited by online, but instead retain a healthy awareness of the fundamental business they are in, whether that be paid or ad-funded content or something entirely new. Creativity in content has long been the differentiator for media executives. However creativity is also required in business approaches, for flexibility of role at all levels of an organisation and operations focused on return rather than the purely artistic value of their output. This talent doesn't need to come from the media exclusively; sourcing talent from other industries may be the best way forward.

New-media talent that is recruited should have a balanced skill set that includes a good commercial grounding and general management capability. Organisations should avoid the dot com era malaise of paying exorbitant fees for talent with little commercial acumen.

Introducing new talent with new thinking and new ideas is important. But ensuring that new talent is integrated in to the organisation and challenged to take good commercial calls is equally critical. As one interviewee reflected:

"... the world where content was king has changed to a world where content is a commodity and commerce is king... our people need to develop new revenue generating models and increase the overall size of the pie."

Richard Titus, CEO Associated Northcliffe Digital.

Having created a diverse, creative and commercially focused team, organisations should ensure that new and legacy talent are able to operate together. Our research interviews identified a point of failure among new media talent: too often it was unable to influence senior management with new ideas. As a result much of the investment made was squandered. It is vital that leaders understand digital and are therefore able to create a talent management strategy that enables both sides of the digital divide to operate together. Emphasising creativity and value creation is the key to this. Both resonate strongly in online and offline worlds and form a common language that breaks down silos. As Arnaud de Puyfontaine, CEO of Hearst UK, National Magazines said:

"I think that every journalist on Cosmopolitan from the Beauty Editor to the journalists should make a success of both platforms. But if I'm talking about how to leverage and monetise, I'm not asking the Editor-in-Chief of Cosmopolitan to become a specialist in transactions. I will need a very different kind of skill set to generate the new revenue streams that are going to be very important going forward."

Changes needed in ways of working

The digital transformation requires new working approaches; deeply embedded ways of working need to be changed. This is a non-trivial challenge.

Media organisations that cannot change may be usurped by more agile competitors and new-entrants. For example, data analytics and real-time consumer insight have not traditionally been core competencies of media organisations; yet advertisers are increasingly expecting this. Looking forward data will become fundamental to any content-based organisation.

"Organisations are not moving to digital for the sake of it, they are moving to a medium where they can count the impact immediately – that is why they are interested."

Derek Morris, COO, VivaKi.

One of the digital revolution's dividends is the provision of an easy to use, immediate return path enabling consumers to feedback to content creators. Previously feedback was limited to point of sale and customer surveys. Digital enables granular and actionable feedback. Furthermore digital storage with accurate metadata means that any content creator can instantly search and use a vast back catalogue from their PC.

"We've invested progressively in our data and our data analytics – making our data much more valuable. It's allowed us to get much closer to our customers and to transform both our business approach and effectiveness."

Rona Fairhead, Financial Times Group.

In future, matching customer profiles, generated through analytics, to the catalogue can produce automatically generated tailored products. The impact on ways of working in editorial and commissioning functions are likely to be deep and fundamental. We strongly believe that media organisations should take advantage of the data that is generated through digital.

Agility as a core competency

All of the above represent huge changes to established media companies, but they are just the tip of the iceberg. In truth the fundamental operational problem for media companies is the accelerating pace of change.

In 2000 Google was one year old; the iPod was two years from launch; Youtube and Facebook were not founded until 2005. Despite their youth, these businesses, their competitors and collaborators have re-written business models that had in some cases lasted for generations.

The truths that we must accept are that the next decade could herald yet greater change and that no one is prescient to identify the next inflection in media business models. It is clear that media organisations must be alert and agile to survive and thrive in such an environment.

"There is no predefined destination, digital organisations are on a process of evolution and the rate of change is breathtaking."

David Pearce, Group CFO, BBH.

In the pre-digital world, where production and distribution were linear, agility was an 'optional extra' that could create a handful of percentage points of value. In the multi-dimensional, multi-channel world of digital it is vital. The challenge the industry faces in the next few years is how to build and embed such a way of working in businesses starved of resources by the traumas of the recent years of negative growth.

Has Media UK gone far enough to ensure a sustainable future?

Media organisations have been in a tough fight for survival in the past 18 months. They have had to take many tough decisions, letting people go and shutting down parts of the business. The question we are posing in this paper is: has there been sufficient focus on the shape of the organisation.

Organisations that have undergone and survived neardeath experiences have been, not surprisingly, more able undertake significant changes to ways of working and business models. For example in local papers journalists are now multi-tasking as photographers and sub-editors. We do not see the same degree of innovation in ways of working at national papers where the crisis has been thus far less severe.

According to Martin Morgan, CEO of DMGT:

"If you look at local press, in many ways you see a more rapid evolution. Why is that easier? Maybe it's because they're looking over the precipice. They got to a point18 months ago where you had to have had your head really deep in the sand not know that you had to change rapidly to survive. It has become much easier to make cultural change in local media than it has been in the national press."

It is in these challenging times that the media sector really has opportunity to re-invent itself. It is often difficult for organisations to justify making challenging or fundamental changes when the situation is 'business as usual' and there is no competitive spur. Resistance to change is now at an all time low and shareholders are now expecting significant change in stance and fortunes.

Shape matters more than size

Organisations have a choice about how they react to tough times the media industry continues to face. The temptation is to respond defensively, by costcutting indiscriminately. This risks the loss of core skills, which could in turn blunt performance. Business leaders need to think strategically, ensuring that their organisations have the right capabilities to meet the future demands head on, and proactively assess the size and shape of their organisations against the business strategy they seek to deliver.

What exactly is meant by size and shape?

Using the human analogy, getting in shape is not just about losing weight; it is also about exercising, to tone muscles and improve flexibility. Too often, the assumption in organisations is that getting in shape is only about losing weight – cut the staff and everything else will take care of itself.

A more proactive approach acknowledges that shape is more important. For example:

- Failure to consider resource numbers in their fullest sense, that is including commissioned services, agency and contract staff, can lead to perverse decisionmaking. Organisations focused on a headcount target may fail to fulfil the original rationale for the target, often cost reduction.

- Considering shape purely in terms of structure, leads to a focus on 'boxes and wires' which may impact management levels, but has limited impact on the front line.

Assessing shape means asking some fundamental questions:

- Is the overall organisational shape optimally configured to deliver the strategy?

- Are the right capabilities, in the right place, in the organisation?

- Are the organisational 'building blocks' appropriate?

- Is the configuration of the leadership team and governance really aligned with the objectives of the overall organisation?

- Are individuals aligned to the organisation's strategy?

Without changing organisational shape, cost reductions risk either staff being asked to do more, or simply less happening. While greater (or at least the same) output can often be achieved by improving efficiency, or by addressing size without fundamental change in shape, the benefits tends to be at the margins and will not meet the degree of challenge (double digit per cent), nor the changing requirements organisations continue to face.

As Arnaud de Puyfontaine from Hearst UK, National Magazines observed:

"When I'm thinking about digital it's not just about what it means in terms of being able to change the operational structure of my business to be more efficient at a cost level. It's about what it does in terms of allowing me to leverage my assets in a way that will give me potential access to new revenue sources as both circulation and advertising revenues are going to be under continued pressure."

What 'being radical' looks like

Experience in large media organisations suggests that targets of 10 percent to 20 percent annual savings are typical. Of this about 60 percent is expected to be delivered by headcount reductions. We would expect to see a compelling business case to be approved before embarking on a headcount reduction programme.

The virtuous circle – headcount reduction whilst investing in new shape

A robust business case should be at the core of any major transformation programme.

Large system change projects have a decidedly unattractive financial and risk profile, typically requiring large upfront investment, and a significant delay between investment and return.

Headcount reduction elements of projects have lower upfront costs, with costs focused around transition: typically in the form of retraining costs and severance packages. The impact of this is:

- the link between transition costs and benefits means that there is a lower financial risk exposure in these programmes; and

- the more modest entry costs make these projects more affordable from a cash flow perspective.

This raises the potential to create virtuous circles of investment: an initial investment is used to generate savings which are then reinvested in a further round of reshaping activities. As a result, small sums of pump priming funding can be used to generate significant savings.

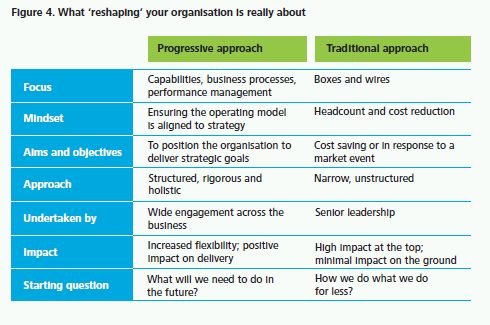

Historically, shaping organisations and structures has often been undertaken myopically. Efforts have typically been in response to a particular event, such as a change in responsibilities, or a need to reduce costs, and focused on defining the 'boxes and wires' that represent the structures and reporting relationships.

New organisations have often been developed in an unscientific fashion based on leaders' perceptions. They have tended to reinforce existing ways of working, silos and mentalities rather than establishing genuine change.

In extreme cases, chief executives simply draw a new structure diagram with a different senior configuration without a clear understanding of how the changes will impact the development and delivery of the product offering. While they may be effective in dealing with short-term challenges, these changes are often found to be unsustainable over the long term.

A progressive approach to organisational reshaping tackles these shortcomings by providing a structure to assess the most effective model to deliver the strategy. The focus is a broad one, considering how the different aspects of the organisation, such as culture, processes and structure, can best be arranged to deliver the organisation's strategy.

Common reshaping themes

Organisations are increasingly exploring fundamental business model shifts. These new shapes tend to be structured around customer segments or product portfolios rather than professional or functional capabilities. They build in flexibility to enable:

- Responsiveness to change: Media organisations must shift existing silos and boundaries and keep them flexible to keep up with ongoing technological change.

- Flexibility of scale: New organisation shapes need to build in flexibility to adapt capacity to meet changes in customer demand.

- Empowering management layers: Most media organisations are seeking to create empowering and enabling (rather than command and control) management layers that allow for creativity, but do not yet have the structures, culture and capabilities necessary to support such an approach.

- Shaping flexible resource pools: Organisations typically contain areas of common skills, processes and responsibilities. There is potential for greater efficiency of working, in particular through working to resolve the issue of how best to utilise content between online and on-air/ print.

- Free flow of information up and down and across an organisation: Data is key in the digital world. Organisations need to be structured in ways that maximise the flow of data and information through organisational boundaries.

Although every organisation project is different, there are a number of common challenges:

- Headcount reduction: Cultural resistance and a reluctance to own the changes.

- Sponsorship/leadership: Many leaders have limited experience of major organisation change.

- Decision-making framework: A tendency to infer too much from incomplete or inaccurate (and thus misleading) information.

- Resourcing: Internal staff rarely have reshaping/redesign experience and skills and may struggle to remain impartial; whereas external resource may lack local knowledge or credibility within the organisation.

- Pace: Organisations may not have the luxury of time, yet hastily taken decisions can have long-lasting consequences. It is important not to lose momentum,

- Stakeholder management: Relations might be difficult if the final project outcome is unknown. Staff must feel involved, but not intimidated by any difficult decisions that are necessary.

- Staying the course: Leaders must be committed to finishing the project, despite hazards during implementation.

Key questions for executives in media organisations.

Chief executives

- Are you clear why each of your portfolio organisations should exist separately?

- When did you last shut down a major programme? Outsource or share a major corporate service?

- How easily can new business models or businesses be accommodated within your organisation?

- Do you have a clear strategy to meet the changing habits of consumers?

- Are your leadership team up for change? Capable of delivering change?

- What new capabilities are required to deliver your strategy?

- Where do you need to partner to execute your strategy?

- Do you have digital media expertise in your leadership team?

- Have you embarked on the necessary preparation for what will be a long process?

HR directors

- Is your manpower plan and strategy tailored to new commercial reality and new strategies?

- When was your last organisational review?

- Are your bonus payments focused on the few genuine top performers?

- Is it easy to move a high-flyer into a major new priority?

- Do your recruiting managers have the knowledge required to attract and recruit top digital media talent?

Frontline operating directors

- When did you last change organisational shape in response to customer demand?

- Have organisational changes saved headcount numbers but increased expenditure on agency staff and consultants?

- How many layers between you and customers?

- Are talent issues holding you back in delivering the business strategy?

Finance or planning directors

- Do you know whether your business initiatives deliver value for money?

- On current cost and headcount trends, how long will it take you to reach current targets?

- Is the organisation in a position to deliver 15 percent cost reduction and what impact would this have on service delivery?

- Is there a clear strategy to monetise new media?

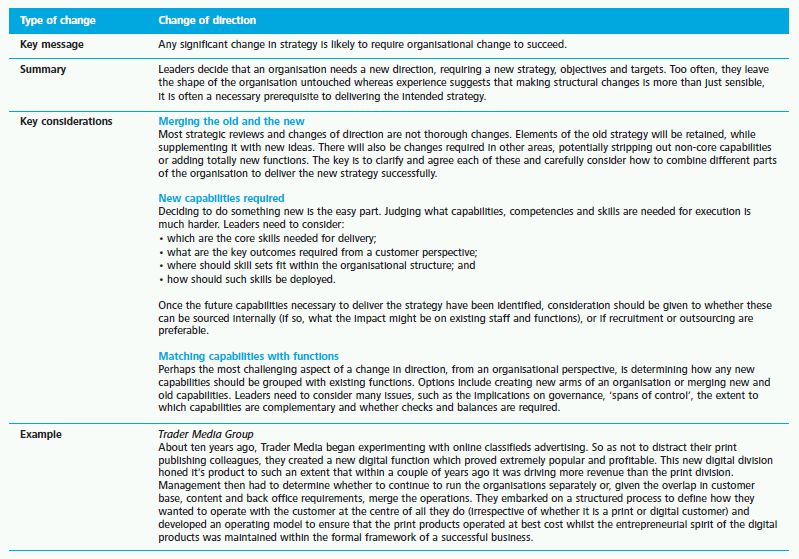

Examples of success in resizing and reshaping

The good news is that there are many examples where changes to organisational size and shape have been well-managed, thus delivering significant benefits. Four such examples are outlined below, with a table summarising the types of changes followed by a more detailed explanation of each.

Conclusion

The long term and ongoing structural change in the Media industry, amplified by the economic crisis has presented a massive challenge. A focus on tactical cuts, particularly headcount reduction, might have brought about shortterm savings but could also damage organisational effectiveness in the longer term. A strategic approach, taking account of structure, governance and culture, can help to identify a more sustainable model for operating in this new reality.

If Media leaders are able to resize and reshape their organisations, they will be in a much stronger position to deliver long term success. Undeniably, such changes will be hugely challenging, yet they could also potentially offer opportunities to deliver reforms that might otherwise be resisted when it is 'business as usual'. For example, redesigning business models with an increased focus on consumers' needs will ultimately lead to improved revenue and profitability.

By drawing on the experiences and approaches outlined in the four success stories in the final section, Media leaders can prepare for the likely pressures ahead. Such approaches can help organisations to develop a size and shape that is more robust, thus enabling them to emerge from the recession stronger and achieve more – with less – in the future.

Footnotes

1 GroupM estimate that the UK advertising market contracted by 14% in 2009 (December 7 2009).

2 Lowest number of media deals since 2002: http://www.guardian.co.uk/media/2010/jan/18/media-deals-pricewaterhouse-coopers

3 National newspapers decrease sales figures – but print remains popular http://www.guardian.co.uk/media/2010/jan/18/roy-greenslade-newspaper-abcs

4 Television viewing figures have remained bouyant through the recession: Deloitte Report "Television's got talent", page 11; https://www.deloitteresources.com/pgContent.aspx?sid=35757&cid=741538

5 Radion figures hold up through the recession: RAJAR 2009/10 http://www.rajar.co.uk/content.php?page=listen_release_dates

6 Newspaper websites attract increasing levels of unique users – but can they make money? http://www.guardian.co.uk/media/2009/nov/26/abces-guardian-mail-telegraph

7 This report highlights the spectacular growth that mobile broadband will experience http://www.ccsinsight.com/company-news/?p=19

8 Enders Analysis: "UK internet advertising: spend flat, share up", October 2009

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.