Regulatory and criminal investigations and prosecutions under D&O policies raise important issues.

Policy triggers for regulatory and criminal investigations can be a grey area. Considerable latitude exists between routine enquires by regulators that are part of business operations (for example a routine request for information by the FSA) and a crisis event that triggers internal and external investigations and dealings with the authorities for dishonesty or fraud. There may be agreement that the first is not an insured risk and the latter probably is, but what about the permutations in between?

Uncertainty is confounded by the absence of a standard D&O wording. Policies may contain separate "investigation" cover. In addition, investigations may also be "claims" under the policy's Side A or Side B cover.

In each case it will be necessary to pay attention to the

expressions that are used as part of the trigger for cover. These

are subject to interpretation, and there is at present little case

law on these areas. For example, if the policy provides

investigation costs cover in relation to meetings that an

individual is "required to attend" does that mean legally

required to attend? Does it depend if there is a penalty for not

attending?

There can also be practical issues in relation to areas such as how costs should be split between claims against individuals and the company, and how to distinguish what is covered and what is not where there are parallel civil and regulatory proceedings. There can often be conflicts of interests between individuals necessitating the use of multiple law firms. Therefore, costs need to be controlled. Finally, conduct exclusions for dishonesty or fraud tend to bite only after adjudication has taken place which can mean that the policy limits will be eroded by dishonest parties, leaving innocent individuals with limited cover.

Another issue that arises is whether the insurer is able to access

information from the insured in relation to an investigation,

without the insured waiving privilege in that information. In

England, common interest privilege is relatively wide, and the

courts are happy to find that such privilege exists between

insurers and insureds where their interests are not identical but

closely related. So, for example in civil litigation, it is likely

that common interest privilege will still exist under English law

even where there is a reservation of rights in place.

In the US, the law on privilege is much more fragmentary and may

vary between the states. Restrictions may be placed by the

regulator on the communication of information to insurers. Insurers

need to comply carefully with such limitations internally to avoid

their own regulatory issue.

Fines and penalties

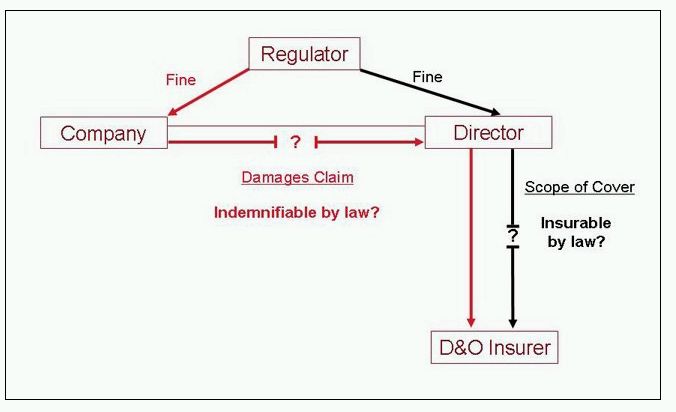

To what extent do fines and penalties fall within the scope of

cover? The basic position is shown by the black arrows in Fig 1.

Under some wordings, there is no coverage, but under other common

formulations, it might only be criminal fines that are excluded,

leaving cover in principle for regulatory fines. There may also be

other restrictions under the policy, for example cover only for

fines and penalties "insurable by law". Even if this

wording is not used in the policy, it arises generally as a matter

of law.

Fig 1

Fines & Penalties: coverage regime

Even if the policy excludes cover for fines and penalties, there is now the concept of "indirect" fines and penalties, which is the situation shown by the red arrows in Fig 1. This was highlighted following the Commercial Court decision in Safeways v Twigger, which is currently under appeal. In short, Safeways agreed to pay a fine to the OFT for allegedly fixing dairy prices. Safeways then sued a number of its directors who it said had been responsible for the relevant price-fixing conduct, seeking to recover the corporate fines as damages for alleged negligence by the directors in breach of their usual duties to the company. This was a straightforward claim as a matter of law, although the issue of whether it is legally valid will be tested further in the appeal. In this situation, the D&O cover is likely to be in play (as it is a claim for civil liability) even if there is an express exclusion for fines and penalties. However, coverage will still be subject to the "insurable by law" test, as the company cannot recover as damages from the director a corporate fine that is not indemnifiable as a matter of law, even if it is the director's conduct in question that resulted in the corporate fine in the first place.

Therefore, the question for coverage purposes is the extent to

which fines and penalties are indemnifiable by law. The relevant

principle of English public policy applied by the courts is known

as ex turpi causa, or the illegality defence. In essence, the court

will not allow a person to recover an indemnity against liability

resulting from his own unlawful conduct.

The Safeways case, and another recent case in the

Commercial Court Griffin v UHY Hacker Young, make

it clear that, for the illegality defence to apply, there must be

an element of "moral turpitude or moral reprehensibility"

involved in the relevant conduct. But applying that test is not

altogether straightforward, although the Safeways

appeal may resolve some of the remaining uncertainties.

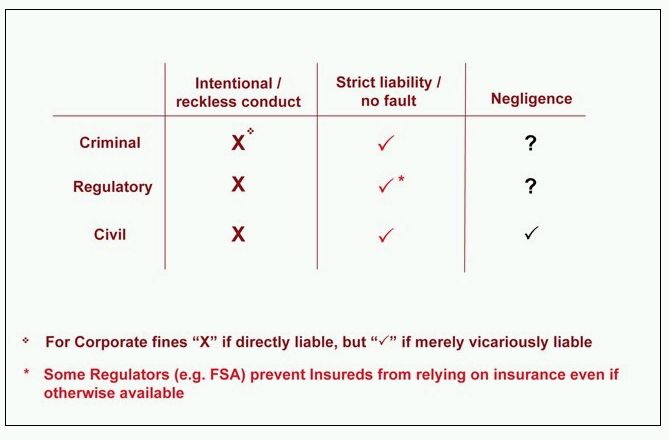

There are essentially three types of conduct for which a fine might

be imposed: intentional or reckless wrongdoing; strict liability

situations, where no particular fault is required; and negligence.

There are also three types of legal regime that can result in

fines: criminal, regulatory and civil. Whilst this is a helpful way

of breaking it down, in practice some of the categories overlap or

cover a wide range of possibilities.

Broadly, however, the position is as illustrated at Fig 2:

- Intentional wrongdoing will not be indemnifiable whatever the type of fine, and might also, in any event, be excluded by other policy provisions, such as fraud or dishonesty, or personal advantage exclusions. But there is a caveat for "indirect" fines: a company might still be able to recover from a director a corporate fine resulting from intentional conduct if the company can show it was only vicariously liable for that conduct. There are difficult issues of attribution here: when do the actions of the directors count as the actions of the company (so the insurable by law test applies), and when do the actions of the directors merely render the company liable under agency principles (so the insurable by law test doesn't apply)?

- Strict liability or no fault fines will be indemnifiable generally speaking across the board. There is a caveat in relation to regulatory fines; the regulatory regime itself or the settlement with the regulator may prohibit those who are subject to it from relying on insurance (something of an increasing trend).

- Negligent conduct is, however, a complicated area. Civil fines or penalties imposed for purely negligent conduct will be insurable, and this would apply to punitive and exemplary damages under English law and, subject to policy wording, to multiple damages awards in other jurisdictions.

Fig 2

Insurable by law? What is clear and what is not.

What is very unclear is the extent to which criminal or regulatory fines imposed for negligent conduct would be insurable. Both Safeways and Hacker Young are examples where such fines were imposed. In the Safeways case, the judge appears to have held they were uninsurable, whereas in the later Hacker Young case the judge seems to have said that they might be insurable. It may be, however, that we will end up with no "one size fits all" approach following the judge's comments in Hacker Young. In the regulatory sphere, there is a huge range of potentially quite different regimes with different degrees of seriousness and different consequences, with the result that, if one has to apply a test of moral turpitude, it may ultimately always be necessary to look at matters on a case-by-case basis.

So the law is in a period of confusion and, typically, in the area

that is currently of most practical significance: regulatory fines

for conduct falling short of intentional wrongdoing. We will have

to see whether the Court of Appeal brings any clarity to this in

the forthcoming appeal.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.