Sign of the times tackling claim inflation

Claim inflation and rising claim costs demand a radical rethink of the way insurance companies approach their claims management. Deloitte’s James O’Riordan and Andrew Power offer a blueprint for the future – the value-based claims business.

A Datamonitor report on "Personal Injury Litigation 2004" states that the number of personal injury claims will grow by only 0.1% in the period 2004-2009 and that motor related personal injury claims have actually declined by 6% in the period 2003-2004. However, Datamonitor also expect claim costs to double in the same period. In addition, the average value of personal injury claims has increased over the last decade; increases not explained simply by general UK economic inflation.

The consequence for general insurers is that they need to manage carefully unit claim costs and claims inflation.

A problem that must be addressed

Legal and medical costs are principally driving this increase in cost. A key factor has been the increasing number of people sustaining a "no fault" personal injury to seek compensation. To some extent, this has been fuelled by US style "no win/no fee" legal advertising.

This seeks to instigate personal injury claims through legal firms, increasing overall claim costs as a result of:

- claims being initiated that would not otherwise have arisen;

- fees for litigation that may not otherwise have arisen; and

- an increased likelihood that claims will be made and claimants will seek legal advice rather than dealing with the insurers themselves.

The primary focus for reducing personal injury claims costs is mitigating legal and medical costs. Notwithstanding this, tight operational cost management needs to be directed appropriately in order to avoid that it does not also contribute to increasing claim costs.

Traditional response is flawed

Insurers are obviously aware of these trends and are searching for ways to address the potential claims explosion.

However, we believe the response is likely to be sub-optimal because the industry will attack the problem using a claims business model that is no longer fit for market. We observe that the general insurance industry manages claims as a volume business, rather than manages it as a value business.

As such it focuses on trying to improve "manufacturing" efficiency by investing large sums in technology solutions to improve throughput. These efforts we believe are misplaced. The drivers for claim inflation are related to issues that are broader than how well claim volumes are managed and the rate of claim settlement throughput. Key will be managing more effectively the broad claims supply chain, involving the full range of claims stakeholders and changing behaviours to managing for value. As such, the operating model for a value based claims business is poles apart from a transaction based claims business.

To illustrate the differences between a value based and a volume based business let us examine how technology is applied to the claims process.

Current systems that are widely used by insurers tend to base their data models, management information and processes around product or customer types. However these categories do not align fully with or take account of varying claim types. For example, a motor claim type can arise on a commercial, private or package policy. From an operational claims perspective the handling and settlement of the claim are virtually identical. Equally, property loss claims transcend many different products; and a large part of property claims follow the motor process.

Some insurers run different products or different channels on different IT packages. This results in claim types, which should have a virtually similar process taking on different processing depending on the system on which they are hosted. As such managing claims for value is impeded as there is no consistency in approach to similar claims types and best practices are dissipated by process fragmentation. A further factor that has exacerbated getting control of claim inflation is system mis-alignment to the claims process. The most fundamental reason for this mis-alignment is that the vast majority (probably 90%) of the activity involved in claims settlement (motor in particular) is conducted with parties other than the customer or broker and relate to cost assessment and third party liabilities rather than policy interpretation.

Best practice for management of claims would require systems based around the 90% activity while still accommodating the other aspects. The result of this is that the claims process has remained very manual and paper based. This has resulted in inefficiency and poor quality information for both operational management and for supporting the business in today’s environment.

The perpetuation of old processes and the traditional approach to claims has inhibited adoption of new business concepts.

The way forward

Primarily good claims management requires the following objectives:

- improve the effectiveness – by paying the right claim amount, being careful to manage potential higher claim cost driven by inflated medical and legal costs;

- improve efficiency – by managing all the participants to deliver the service at lowest cost;

- improve management indicators – creating the most effective Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) to drive appropriate actions to deal with claim inflation; and

- reduce costs – by delivering superior customer service to all customer types.

Most claims organisations today would probably ascribe to these objectives. However for most insurers their claims practices would prevent achieving the objectives. To remedy this, critical actions that the claims organisation needs to focus on are to influence the claims process and control all costs associated with the claim.

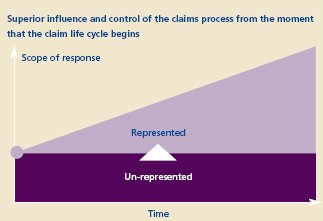

The claimant is much more likely to seek legal representation the longer the time between the event and the insurer’s response. It is absolutely critical to maintain control and influence over the channel a claimant could take once an "event" has occurred. It is well documented that claim costs will be much higher if the claimant seeks legal representation.

The more effectively claims are dealt with at the notification stage the more responsive the insurer can be to the needs of the claimant rather than to the legal representative. This maximises the potential for the claimant moving from an un-representative position to legal representative position.

Managing the time line for claims resolution will have a direct impact on the size of the claim settlement, be it the cost of administration and management as well as the cost of the personal injury settlement. One of the key principles for an effective claims service is to add maximum value to a claim at notification. This enables a claim to be directed in a manner that minimises cost to the insurer. It also facilitates obtaining the maximum amount of information to enable early assessment and minimise opportunity for exploitation. In addition, the delay and cost of conducting investigation subsequently is minimised. In order to do this, good quality and well-trained staff must be engaged.

At the event point, the claims process will begin. Have a clear claimant proposition with a supporting end to end process that is configured in the organisation to achieve this. Each channel that receives and manages claims needs to be configured to reflect and respond to the position of the claimant at the outset of the claim life cycle and trigger points should be defined that reflect changes in the claimants preferred channel (e.g. a move to litigation), as this will change the response from the end to end process.

Control all costs associated with the claim

To address claims inflation, insurers need to control all costs associated with a claim settlement. In reducing claims spend (or keeping inflation lower than what it would otherwise have been), it is necessary to understand and manage and control all costs associated with the claim. Each cost element at aggregate, claim type, participant or other level The claims process is rife with data but often lacks useful information.

While systems can impede getting the right information there tends to be a lack of clarity around the definition of key information. By defining what drives claim costs, management can pinpoint the required information and develop the required understanding around what levers to pull to optimise claims value. Once a good understanding exists it’s possible to take management action, such as bulk purchasing, changing processes to reduce creation of cost, changing product covers, lobbying government, etc.

Each claimant or other participant who creates cost

While claims organisations have normally mapped claims processes down to a fair degree of detail there has often been less clear tracing of where costs are incurred and how much each claim’s participant influences costs. Once this has been determined down to individual level, action can be taken with individuals or groups of individuals who incur cost items, which are higher than other similar parties. Examples include claimant solicitors who exploit certain cost elements, perpetual claimants, garages who inflate repair costs, and doctors who replicate questionable injury complaints.

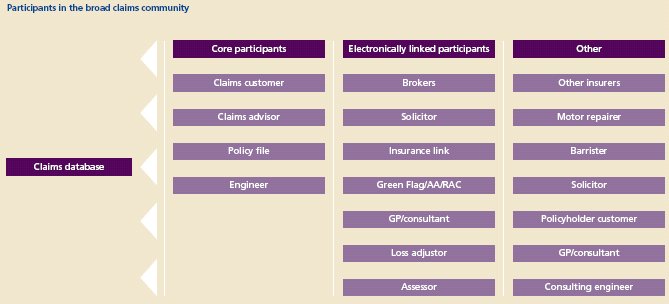

Performance of each person whose job it is to assess and minimise cost (whether internal staff or external service providers) Insurers engage specialist resources that possess suitable skills to assess and negotiate individual claims elements in order to minimise cost. These may be internal staff or external service providers. It is important to be able to measure the effectiveness of the work of each down to individual level. One of the fundamental approaches to claim processing and settlement is the recognition that there are many more participants in the process than just the insurer’s claims staff.

Most of these participants make key decisions on their behalf or supply key information to the insurer.

The diagram below identifies the participants in the broad claims community:

Every participant provides information, makes choices or makes decisions as part of the process and as such is the source of certain data/actions. They also can add significant cost to the final settlement of a claim. Each one of these participants needs to be managed and treated as an end customer in itself. Clearly defined strategies and agreements where possible will influence their impact upon claims cost. As referred to above, the broader claims community outside the insurer’s own staff could account for up to 90% of the activities on a claim (especially in motor).

Developing a value based claims business

A value based claims business requires a new claims philosophy, management of internal staff and engagement with all other participants to co-operate towards the key objective of paying the right claims amount to the claimant in an effective and efficient manner.

A value based claims business requires:

- understanding what fuels claims inflation;

- getting early control of the claim through influencing and managing the whole claims community;

- maximising the opportunity at notification to minimise unnecessary legal representation;

- managing effectively all elements of the claims cost; and

- developing and managing measures of claims value not just volume.

As such, a value based claims business will develop an operating model that:

- designs processes and systems to operate in a single environment accessible to all parties who need to participate in the process;

- segments claims activities to target processes differently between simple and complex claims;

- works with all parties to the process to migrate as much information as possible from hard copy to structured electronic format at source;

- develops open, structured claims handling systems, which will equally interface to core systems and e-service solutions with all parties to the claims process; and

- adopts a data model, which provides a deep level of data which can be mined to support automated processing and managing performance of all participants, portfolios of claims and claim cost elements.

Clearly moving towards such a value based business requires an integrated change programme that does not just rely on the technology elements. We have seen too many claims change efforts disappoint due to over reliance on the "magic" of the new or upgraded technology. More importantly, we have found, are the behaviours needed to change both internally and within the broader claims community. This will not occur overnight but will require a sustained effort to define clearly what behaviours are expected for each major claims event and at each stage of the claims process. Too many claims initiatives have failed to reach their goals due to misalignment between desired and actual behaviours, which normally is due to lack of clear definition and communication around expectations and an inability to track progress.

James O’Riordan Andrew Power

The transfer experts

The role and significance of the independent expert is evolving following regulatory changes to the process for Part VII insurance business transfers. Deloitte’s Alex Marcuson and David Hindley review the emerging themes and highlight some concerns for the future.

The role of the independent expert in business transfers has evolved over the past five years under the umbrella of Part VII of the UK Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA 2000). The Act enables the transfer of policies between companies, subject to court approval. In practical terms, this requires the FSA approval and a report from an independent expert.

Whilst not specified by regulation, the trend now is for the expert to be an actuary; previous legislation meant that this was standard practice only for life insurance business. It is now not unusual for non-life insurance business transfers as well. This move reflects the emerging role of the actuary in advising in an increasing number of areas of non-life insurance operations.

The role

The independent expert’s role is to consider the scheme from the point of view of the various classes of affected policyholders. In simple cases, this might involve no more than looking at things from the point of view of the transferred policyholders, those left behind, and those in the receiving or transferee company. However, for some of the more complex transactions, several groups must be considered, especially if there are a number of companies involved in the transaction.

The expert looks at both the financial and non-financial implications of the transfer. The regulations are not prescriptive, so it is for the expert to determine what is needed on a case-by-case basis.

Finally, the expert prepares a report for submission to the UK High Court. The court has tended to rely on the FSA to be satisfied by both the terms of the transfer and the report prepared by the expert.

The process can be neatly summarised by the three Us: understanding, unravelling and unbundling.

Understanding the risk and capital trade-off

In the report the expert will need to communicate the risks to the various classes of policyholder considered, before and after the transfer. This will require the expert to understand them and to evaluate how much capital is required in each company where policyholder liabilities are situated after the transfer is completed. For example, if policyholders move from a highly capitalised company to a less well capitalised one, the risks will need to be commensurately reduced for the transfer to be possible. How much work is needed here will vary from transfer to transfer and the extent to which the affected companies have already addressed these issues.

Unravelling complex security structures

Often transfers are driven by the desire to tidy up portfolios that have a legacy of differing owners. In arriving at their current form, regulators have often demanded guarantees and other indemnities to provide continuation of security to policyholders. In completing the work, the expert will often assist in quantifying the impact of cutting these ties and considering equivalent replacement options.

Unbundling components of transfer

As transfers often take place as part of a wider corporate restructuring process, the expert will need to consider which changes form part of the transfer. Often the status quo is not a viable option, so a comparison with policyholders’ existing position is not the correct test for the expert to perform. The expert will need to consider how to identify what the implicit elements of the transfer are and structure the analysis accordingly.

Emerging themes

There are a number of themes that are common to many transfers taking place at the moment.

- Capital adequacy and expert advice – In the UK, the FSA has recently launched the Individual Capital Adequacy Standards (ICAS) regime. This approach follows the three-pillar Basel architecture approach adopted for banks, namely: capital adequacy, supervisory review and market discipline.

The emerging role of actuaries in helping companies to implement the ICAS regime, especially with regard to capital needs and business uncertainty, means that companies often benefit from explanations and suggestions of the expert in the construction and communication of any transfer. This is particularly important when addressing the "three U’s" described above.

- Apples and pears – There are two broad types of transfer: internal and external. Internal transfers involve companies from only one group; external ones do not. For both, it tends to be the norm that there is little similarity between the companies when size, risks, diversity and financial strength are considered; the expert is forced to compare two very different arrangements.

A variant of external transfers is the two-into-one type. Here, companies are trying to break up past associations and crossguarantees to reduce on-going uncertainty. Through chance circumstances of history, policyholders will have found themselves benefiting from the security afforded by two companies. Here the expert must evaluate the marginal benefits that the second company provides to policyholders in deciding whether replacement is sufficient.

Often these transfers are being used by companies as steppingstones to finality, enabling companies to divest themselves of discontinued or non-core insurance operations. Part VII transfers can provide a direct mechanism where a suitable counterparty can be found. Where this is not the case, a restructure program using a Part VII transfer can put the discontinued business in a separate operation that can be spun-off or a scheme of arrangement can be arranged with policyholders.

- Reinsurance – The security of transferring policyholders often depends on the transfer of reinsurance protections. Ideally, the parties to the transfer will ensure that the reinsurers are happy with the proposals and that the contracts permit the change. Where a reinsured portfolio is being split, it is necessary for the expert to consider if and how the cover can be divided. For some covers this may prove challenging.

- Multidisciplinary teams/solutions – In the more complex transfers, for example two-into-one type transfers, it is often necessary to develop innovative solutions to meet policyholders’ security requirements at minimal cost to companies. Our preferred approach is to ensure that the expert has access to a multidisciplinary team with the skills to evaluate properly alternative security markets, guarantees, and overseas considerations that companies put in place.

Future challenges

There are a number of areas to watch that can be expected to develop over the next couple of years that may affect how transfers are carried out.

- Non-EEA policyholders – The position regarding non-EEA policyholders, and whether the transfers under the Act can be made binding, remains unclear. In the US, a judgment in 2004, Rose, suggested that it may not be possible for companies to prevent US policyholders from taking legal action to protect their position. As a result, care is needed in structuring the transfer and the expert’s work to accommodate this uncertainty.

- Independence issues – This is an area which is changing globally, particularly as advisers adjust to emerging auditing standards. With few formal rules and practices set down to date for independent experts, this appears to be an evolving area. A particular issue for regulators will be the tension between a desire for as much independence as possible (both real and perceived), and the limited number of service providers with the appropriate expertise in some specialist areas. The need for the expert to provide input and advice on the transfer further confuses the issue.

- Potential for policyholder challenge – As yet, there have not been any major, widely publicised challenges to a transfer under the Act. This always remains a possibility as companies increasingly seek to effect restructures. Hopefully, a well-managed transfer with an experienced team should be able to limit the possibility of dispute – however, with increasing levels of litigiousness in society the prospect of an action group forming to oppose a transfer should not be ruled out.

Drivers for change

- Untangle past relationships

- Consolidate portfolio to release capital

- Remove capital intensive guarantees and indemnities

- Exit non-core lines

- Stepping stone to finality

Transfer challenges

- Lack of comparability of companies

- International policyholders

- Complex guarantee structures to unwind

- Cross-border transfers

- Separating transfer from other restructuring activities

Conclusion

Insurance business transfers under the Act are becoming commonplace as companies seek to respond to the changing regulatory climate and refocus their business to core, high-performance activities. Established processes and methodologies mean that, while no corporate restructure can be assumed to be necessarily simple, companies, regulators and advisors are converging on common approaches to tackling the problems these transfers can present. There are a number of areas to watch how practice will develop over the next few years, particularly in the areas of: non-EEA policyholders, independence and legal challenge. Despite these, transfers under Part VII of FSMA 2000 are an important addition to the arsenal available to insurance executives that look set to stay.

Article by Alex Marcuson, David Hindley

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.