Foreword

By John Connolly

In this Review, Roger Bootle, Economic Adviser to Deloitte, looks at whether UK exporters are in a good position to take advantage of the opportunities created by the robust world economy. His review continues on to gauge how the future of the UK economy may be influenced by these opportunities.

Roger believes that in the long-run the key is for UK businesses to tap into the large and rapidly developing markets in Asia, principally China and India. At the moment, the UK’s exposure to these countries is tiny, suggesting that the gains over the next few years are unlikely to add up to much. Although UK businesses are in a prime position to benefit from the economic recovery in the euro-zone, Roger believes that the scale of recovery there is likely to be modest compared to what is needed to impact much on UK trade.

There are also attractive prospects for selling to the oil exporting countries, which have large stockpiles of cash to spend. Although the UK’s presence in these markets is large, Roger notes that they do not account for a very large proportion of British exports so any gains may be modest. Furthermore, Roger warns that the outlook for businesses heavily exposed to the US may be about to take a turn for the worse, as the US economy is susceptible to an economic slowdown.

Roger believes that if UK exporters are going to contribute noticeably to economic growth it will take a lower pound to improve the UK’s competitiveness. This can by no means be predicted with confidence but lower domestic interest rates at the same time as rates continue to rise abroad could bring it about, sowing the seeds for a gradual, healthy rebalancing of the economy and a strengthening of economic growth.

Once again, I hope that this Review helps you in both your immediate and strategic thinking.

Executive summary

- The strength of world demand has finally put the necessary conditions in place for the UK’s external sector to take over from troubled consumers and drive the economy forward. However, the UK is not well positioned to make the most of the clear opportunities that lie before it.

- The large and booming markets of Asia, such as China and India, provide a golden opportunity for UK exporters over the long-run. The resurgence of a more established nation, namely Japan, improves the prospects for UK exporters further. But the UK’s presence in these markets is tiny, suggesting that the gains over the next few years will not amount to much.

- Instead, the UK is heavily exposed to the euro-zone, sending over 50% of its goods and services exports to the single currency area. In this regard, the good news is that the euro-zone finally appears to be emerging from its torpor, with the optimism of the forwardlooking surveys having finally started to show up in the hard activity data.

- The likely scale of any euro-zone recovery is modest compared to what is going on in Asia, and compared to what the UK needs to have much of an impact on its trade balance.

- The best prospect in the next few years may appear to come from the oil exporting countries, which are sitting on large current account surpluses thanks to the high oil price. The UK’s presence in these markets is large. However, they do not account for a very large proportion of British exports so even a big increase would not transform our trade.

- On top of all this, with the UK sending 18% of its exports to the US, the prospect of a housing market-led US economic slowdown over the next year or two could further dampen the potential for strong UK export growth.

- Asia may hold the key in the long-term. But if the external sector is to shoulder the burden of propelling UK growth over the next couple of years, it will take a lower pound to increase the UK’s competitiveness.

- That is something which monetary policy could help to bring about. With the weakness of the UK economy over the last 18 months implying that underlying inflation pressures have further to fall even if growth accelerates above trend, the prospect of a significant undershoot of the inflation target will bring interest rate cuts back on to the Monetary Policy Committee’s agenda in the second half of the year.

- With interest rates in the US now higher than in the UK, and with euro-zone rates likely to rise to 3.5% by the end of the year, further UK rate cuts may bring about the fall in the pound that the external sector so badly needs.

- This would not necessarily mean that the UK economy is set for a phase of rapid growth. Indeed, with the consumer slowdown yet to run its full course, GDP growth is likely to accelerate only modestly, to around 2% this year and 2.5% in 2007. Can exports deliver the goods?

Can exports deliver the goods?

Over the last 10 years the Monetary Policy Committee’s policy has been to offset the weakness of external demand for the UK’s output by stimulating domestic demand. This policy has largely worked but it now looks to have run its course.

With consumer spending growth still weak, any rebound in the overall will require much higher exports growth. So over the next two years UK GDP growth, and all the various things dependent upon it, such as the level of unemployment, tax receipts and government borrowing, will largely depend upon events abroad. Could a strong world economy be the launching pad for a rebound in UK growth?

UK exporters have lagged behind

The performance of the UK’s external sector has been pretty dire over the last ten years, with net trade failing to make a positive contribution to GDP growth since 1995. Meanwhile, the UK’s share of world goods exports has continued to decline. This is not a disaster as it partly reflects the development of other countries and the shift in UK activity from the manufacturing sector to the services sector.

However, the UK’s share of world trade has declined by more than its closest international competitors. The UK had the third largest export share of the G7 nations in 1960, it now has the second smallest.

The UK’s exports of services have done better but not by enough to make up for the weakness in goods trade. In 2005, the UK’s deficit in trade in goods and services widened to a record high of £47bn, some 4% of GDP. And the current account, the overall measure of the UK’s transactions with the rest of the world, is now in deficit to the tune of £32bn – a record high in cash terms – or 2.6% of GDP.

A new hope

All this might be about to change. In 2004, world GDP rose at its fastest rate in 30 years and, despite a slight slowdown in 2005, growth is expected to remain robust over the next few years. Indeed some factors suggest that it might pick up. Historically, rapid rates of world GDP growth have been consistent with strong growth in UK exports.

But will this be enough to lift the UK’s external sector out of the doldrums? There seem to be three main opportunities:

- Rapid growth in some Asian nations.

- The economic recovery in the euro-zone.

- The cash surpluses of oil exporters.

But there is also at least one major threat, namely a prospective economic slowdown in the US.

In what follows, we consider the size of these opportunities and threats and what kind of impact they could have on the UK economy.

The rapidly growing Asian nations

It is generally thought that the greatest opportunity for UK exporters, certainly over the long-run, comes from the rapid development of some Asian nations. Countries such as China and India have started to suck in imports on a vast scale. For instance, over the last five years Chinese imports have risen by an average of 25% per annum.

This growth has propelled China to the position of the world’s third largest importer.

UK exporters have already benefited from the rapid rates of Asian growth. Indeed, in 2005, the UK increased its goods exports to China and India by 19% and 25% respectively. These were much larger increases than those posted by exports to slower growing economies such as Germany, France and the US. But there is a rub. The UK’s exposure to these fast growing Asian nations is very small. Indeed, in 2005 the UK sent just 1.3% of all its goods exports to each of India and China. In contrast, it sent over 50% to the slow-growing euro-zone economies.

This imbalance is shown more clearly in Chart 7. The vertical axis shows various countries’ GDP growth and the horizontal axis shows the share of the UK’s goods exports that these countries receive. From the point of view of the UK’s export prospects, the most advantageous pattern would be if countries fell on the diagonal line. That would mean that the countries with the highest growth rates took the highest share of UK exports, and the lowest took the lowest share. By contrast, the least favourable pattern would be for the observations to cluster towards the two axes. That would mean that the countries with the highest growth rates had the lowest share of UK exports and countries with the lowest growth rates had the highest share of UK exports.

Unfortunately, the observations in the chart do cluster towards the axes. In other words, the UK’s trade is heavily skewed towards countries which are not growing very fast.

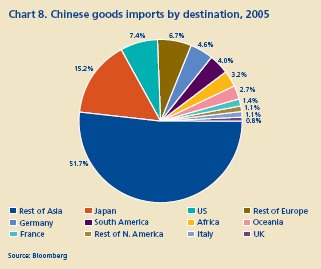

Indeed, it is striking that the UK is less exposed to Asia than most of its leading international competitors. Chart 8 shows the geographical origin of China’s goods imports in 2005. At 0.8% the UK’s share is less than Italy’s 1.1%, and France’s 1.4% and it is much smaller than Germany’s 4.6%.

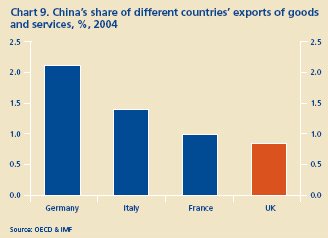

It is tempting to believe that once we take account of services the UK’s position will be redeemed. Data deficiencies make direct comparisons impossible but we are able to compare China’s share of the exports of both goods and services for Europe’s four largest economies. Chart 9 shows that even when you take account of services as well as goods the UK’s exposure to China is the smallest of the four.

In the short term at least, it is unlikely that the UK economy will benefit to any significant degree from further rapid growth in these Asian economies. Sticking with China as an example, if the UK’s market share of Chinese imports remained at 0.8% and Chinese imports continued to rise at an average rate of 25%, this would increase UK exports by just £0.8bn per year. As a percentage of nominal GDP it amounts to just 0.07%.

If we doubled this figure to take account of services and we totted up the effect over two years this would amount to a more impressive 0.26% of GDP. But to arrive at a net impact on the UK economy we also need to take into account the trend increase in UK imports coming from China. Over the last five years the value of the UK’s goods imports from China has increased at an average rate of 22%. If this were to continue then UK imports from China would rise by around £2.8bn per year, or 0.23% of GDP. This suggests that the net impact on the UK economy of increased trade with China could be to reduce UK aggregate demand.

Admittedly, the impact on the UK would be more favourable if the UK increased its market share of these countries’ imports. And it is possible that the UK is in a good position to do this. So far import demand from these nations has been concentrated in investment goods.

This has played into the hands of the euro-zone nations, particularly Germany, which produce a greater proportion of investment goods than the UK. But as these Asian countries develop further, demand will switch towards consumer goods, which the UK is better positioned to supply.

What’s more, further development will see Asian demand increasingly switch to services. And as the UK is the second largest services exporter in the world, behind the US, it is well placed to take advantage.

Although these are realistic developments that could work in the UK’s favour in the long-term, it is somewhat naive to expect the UK to raise its market share of developing Asia’s imports to any significant degree over the next few years.

Japan to the rescue?

Could further benefit come from a more established country, namely Japan? When measured at market exchange rates, Japan remains the second largest economy in the world. And it looks as though the long Japanese deflation nightmare is ending. The Japanese economy is set for a fourth successive-year of above trend growth. Continued recovery will provide a boost to the world economy - and to the UK.

However, the UK’s exports to Japan make up only 0.1% of Japan’s total goods imports. Even if Japanese imports were to rise by 25%, this would increase UK exports by only £0.4bn per year, or 0.03% of GDP.

Despite the vast opportunity that the rapidly growing Asian nations represents for UK exporters in the long-term, it is unlikely that over the next few years our trade with these countries will have a significant helpful impact on the UK economy. Indeed, the overall impact could well be negative.

The euro-zone economic recovery

A much more realistic near-term opportunity for UK exporters appears to come from the euro-zone’s economic recovery.

In the last six months, the improved tone of the forward-looking surveys has started to crystallise in the hard activity data. UK exporters are apparently in prime position to capitalise on this as they send 50% of their goods and services exports to the single currency area. There has been a reasonably close relationship between GDP growth in the euro-zone and changes in the UK’s goods exports to the euro-zone over the last 15 years or so.

This relationship, when taken at face value, suggests that euro-zone GDP needs to be growing at a rate of 1% just for the level of UK goods exports to the euro-zone to hold steady. And every subsequent 1% increase in euro-zone GDP growth increases UK exports by 5%. If the same relationship held for services then the total increase in UK exports would be about £7.3bn.

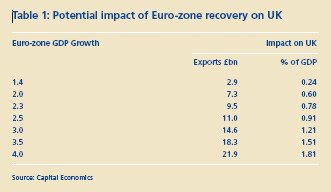

Using this rough rule of thumb we can attempt to quantify the impact that the euro-zone economic recovery may have on the UK. Table 1 does this by showing the possible increases in UK exports from various rates of euro-zone GDP growth.

It shows that euro-zone GDP growth of 1.4%, would increase UK exports to the euro-zone by just under £3bn, or 0.24% of the UK’s GDP. And an acceleration to 2% would increase UK exports by the equivalent of 0.6% of GDP, while if the euro-zone economy grew at a very robust rate of 4% this would add 1.8% to UK GDP.

Recovery in the euro-zone does have the capacity to have a huge impact, not only on British exports, but on the UK economy overall. Unfortunately, though, we doubt that the euro-zone recovery will be strong enough to realise this potential. Our forecast is for the euro-zone to grow by 2.3% this year and by 2% next. These forecasts are above the consensus.

Based on our forecasts, the impact on UK GDP growth could be in the region of £9.5bn per year or 0.8% of nominal GDP.

Again, though, we need to also take into account the upward trend in UK imports from the euro-zone, which have been rising at an average annual rate of just over 5% for the last few years. If this were to continue then the UK would increase its imports from the euro-zone by £8.8bn per year, or 0.73% of nominal GDP.

That said, whether the euro-zone recovery has any impact on the UK economy at all depends on the shape and location of the recovery. Obviously, the worst possible scenario is if the euro-zone recovery is export-led, as the UK would then feel no benefits at all.

Thankfully, with income growth and employment in the single currency area likely to rise, consumer spending is likely to be the driving force behind the developing recovery. What’s more, it is highly likely that the euro-zone recovery will be largely driven by an acceleration in German economic activity. Given that Germany takes a larger share of UK goods and services exports than any of the other euro-zone nations – 9.7% compared to 8.5% for France and 4.0% for Italy – this further plays into the hands of UK exporters.

Even so, after taking account of the trend towards increasing UK imports from the euro-zone, the net impact of faster euro-zone growth is still likely to be very small, possibly in the region of £0.7bn, or 0.05% of GDP.

The cash surpluses of oil exporting nations

A further key opportunity for UK exporters comes from the oil exporting nations which, due to the sharp increases in the oil price, are sitting on large amounts of cash. In 2004, Norway, Russia and the eleven oil producing nations of OPEC earned a cumulative $490bn from exporting oil.

Admittedly, this does not all constitute "spare" cash as these countries use their oil revenues to buy other goods and services. But taken together, they are still running a current account surplus of $230bn.

We have no data on what proportion of the oil exporters’ goods imports come from the UK. But we can make an educated guess using the UK’s current share of world exports of 4% as a starting point.

Because of close links with the UK, it seems likely that these nations are relatively heavy importers of UK services. As such, an estimate that between 6-8% of the oil exporters’ total imports may be sourced from the UK does not seem too implausible. Taking the middle point of this range, if the oil exporters were immediately to spend half of their current account surpluses then UK exports could increase by £4.4bn, or 0.4% of GDP.

Again, though, this positive for UK GDP growth is likely to be offset by the UK continuing to increase its imports from Norway, Russia and the OPEC nations. If this continued at recent rates then it would just about wipe out the benefit of these countries halving their current account surpluses.

The US economic slowdown

Not all prospective developments in the world economy are positive for the UK. Although the US economy weathered the adverse effects from Hurricane Katrina to record GDP growth of 3.5% in 2005, there are growing concerns that a sharp housing market slowdown will lead to slower growth in the coming years, and perhaps even to a recession.

The US economy is not as important to UK exporters as the euro-zone. But it still takes 18% of all the UK’s goods and services exports. There is a fairly close relationship between changes in US GDP growth and the growth rate of the UK’s goods exports to the US.

At face value this relationship suggests that US growth needs to run at 2% for the level of UK exports to remain stable. And every subsequent 1% increase in US GDP growth is then consistent with a 2.5% rise in the level of UK exports, or about £2.8bn in cash terms after taking into account services trade. This seems to tally broadly with the £7.3bn increase in UK exports from an extra 1% of euro-zone GDP growth estimated earlier, given that the UK’s exports to the US are around two-fifths the size of those going to the euro-zone.

We can use this relationship to provide a guide to how a US economic slowdown could affect the UK economy. Table 2 shows that if US GDP growth remained at 3.5%, increased UK exports would add £4.2bn to UK GDP, or 0.35%. A slowdown to 2.5% would still see UK exports rising and this increase would add £1.4bn to UK GDP, or 0.23%.

It is only when US growth falls below 2% that the UK’s exports to the US are likely to fall outright. A slowdown to 1.5% would take £1.4bn off UK GDP while zero growth in the US would cause a drop in exports equivalent to about £5.6bn, or 0.5% of the UK’s GDP.

Although the threat of a severe US slowdown, and perhaps even a recession, remains, it is much more likely that the housing market slowdown prompts only a modest slowdown in US growth over the next two years or so. An easing to 2% would, of course imply lower UK exports than in the scenario of 3% GDP growth but exports would probably be at about the same level as now.

Given that UK imports from the US have fallen by an average of 5% over the last five years, it is likely that the net impact from our trade with the US over the next year or so will be marginally positive. However, the possibility of a sharper US slowdown remains a serious threat.

The net impact on the UK

Bringing all this together, Table 3 shows the likely total impact on the UK economy from the various opportunities and threats discussed above. It suggests that the UK economy will benefit only very marginally from the changing global scene.

The upshot is that although robust global demand has produced a number of clear opportunities for UK exporters, the UK is not very favourably placed to take advantage of them. This conclusion does not rest on the assumption of a sharp negative effect from an assumed US slowdown over- whelming a strong positive influence from Asia. On the contrary, in our calculations, trade with America is a net positive for the UK.

The small size of the positive effect for the UK arises largely because the UK has a small presence in the areas that are growing rapidly. Given the current distribution of the UK’s exports, what a large boost to UK exports requires is a really strong revival in the euro-zone. Unfortunately, the likely revival in the euro-zone will be feeble by comparison.

The sterling exchange rate

So what will it require to transform the UK’s export prospects? In the long-term, the answer is clear: a shift towards the fast growing markets of the world. In the short-term, though, the answer is something much more prosaic – a lower exchange rate.

The strength of the pound has been a thorn in exporters’ side since the sharp appreciation in 1997. Given that the UK’s interest rate advantage against the euro-zone is likely to diminish further over the next few years, and that US rates have recently risen above those in the UK, a significant weakening in the pound is now a distinct possibility.

Although there are some persuasive arguments why the sterling exchange rate is no longer as important as it once was, a fall in sterling of 10% or so, if it were finally to occur, could provide UK exporters with a significant boost over the next couple of years. Meanwhile, to improve longer-term prospects they undoubtedly need to look East.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.