When metals and mining companies first started to report on environmental performance, there may have been a feeling that a long journey was just beginning. Now the broader context of sustainable development ("SD") is well established, albeit evolving and with significant challenges.

Metals and mining companies, like all businesses, focus on financial viability and profitability. Layered across this are numerous sustainability challenges that, for the largest companies at least, are well recognised. The sector’s environmental and social footprint can be significant, with impacts at local, regional, national and global levels.

As a primary industry driven by metal and mineral geology and thus frequently operating in remote and non-industrialised parts of the world, sustainable development performance has been under the spotlight for several years. In response, many companies have taken large strides to manage and report on relevant issues and the sector has become one of the top SD reporters, producing 800 reports since 19921.

Those companies leading SD reporting in this sector have their challenges in how to:

- make reports accessible to stakeholders;

- demonstrate improvements in performance;

- ensure stakeholders trust the published information; and

- make sure the focus is on key risks.

Those companies not reporting, or providing little more than brief statements also have their challenges:

- why should they report more;

- how should they be reporting;

- how can they be confident in the information they publish; and

- what information should they be reporting?

This publication sets out findings of research undertaken into current reporting practices in the sector, looking at what the best reporters are doing well, and providing pointers for those companies that have not yet fully embraced the SD reporting challenge. The 36 mining companies covered by the survey reflect the range of company sizes and geographical coverage within the industry and is based on the reports available in July 2006.The sample comprises 19 large companies with market capitalisation above US$ 5b, 7 medium companies with market capitalisation between US$ 860m to 5b, 3 small companies with market capitalisation up to US$ 860m and 5 non-listed companies (termed as "other") – Appendix 1 provides an overview of the sample.

SD reporting is a commonly used term in the mining industry, whilst many other sectors prefer the term corporate responsibility. Whilst definitions may be debated, for the purpose of this paper we use the term SD.

Current state of SD reporting and assurance.

The broad picture of the areas for SD reporting was established by the Global Reporting Initiative ("GRI") guidelines for the mining sector, endorsed by the International Council on Mining & Metals ("ICMM") and has been widely used by top reporters. UNEP, Sustainability and Standard and Poors2 analysis and ranking of nonfinancial reporting found that all of the top 50 referenced the GRI, with 24 stating they were in accordance with it. Our survey found that 16 of the 34 mining companies reviewed used the GRI, including 9 using the specifically developed GRI mining supplement.

Within the mining sector there is a wide range of reporting types, from substantial standalone and web-based reports with analysis of key issues, associated data, indicators and targets, to summaries of issues included in the annual report, and companies that report little or nothing of their SD risk, impact or management practices. The chart overleaf sets out, by size, how companies are reporting3.

As expected, reporting is dominated by large organisations, with medium and small companies primarily reporting in the annual report and accounts ("AR&A").

In all, of the cross section of 36 companies surveyed, 18 produce a stand alone report and only 5 do not report. In the following analysis of what is reported, the 5 non-reporters are excluded.

What is being reported

Many mining reports are substantial, with a large volume of quantitative and qualitative information. The graphs (opposite) highlight key areas being reported on by the selection of mining companies we reviewed4.

Several points emerge from our review of SD report content:

Environmental reporting

For environmental reporting in particular, the reporting challenge is to facilitate stakeholders’ understanding of the data presented. The rise and fall of indicators across time tells some of the story, but greater sophistication may be needed to understand fully SD performance. What does the volume of water use mean when its impact is dependant on water availability? What does energy use mean when it is the relative carbon intensity of that energy that is important?

Therefore a fuller picture of environmental performance may be shown through KPI’s that, rather than describe how much is consumed or generated (energy consumption, waste generation), or what is being done (how many sites are certified to ISO 140001, delivery of targets), demonstrate the actual impact on the environment such as the reduction in carbon intensity of energy used, or improvements in local air quality. Ideally the reader wants to know what the real environmental impact is, but to achieve this requires greater sophistication in understanding environmental limits and carrying capacities of environments surrounding operations5.

In addition, it should be noted that reporting does not necessarily equate to good performance. Despite extensive reporting, a recent study by Ceres6 evaluated how 100 companies are addressing climate change. The large mining companies were once again ranked middle tier highlighting that still more needs to be done.

Financial indicators

A recent development has been a move towards financial accounting for environmental costs as environmental impacts have attracted more significant direct financial consequences. Mine closure provisions, the subject of another Deloitte publication, and carbon liabilities are the beginnings of this trend. This may go beyond environmental liabilities, with one company reporting a social provision for obligations around skills retraining and community activities. Further financial indicators may come in the form of environmental taxes, increasingly common and advocated in Europe, such as for waste disposal and energy use.

Impacts on ‘fenceline’ communities

Coverage of the management of human rights and of the process of engaging and working with communities impacted by mine operations and developments is increasingly being reported. This is a challenging area which is now handled proactively by many mining companies. Whilst many benefits arise from mining developments, such as improved infrastructure, there are also negative impacts. These include loss of land and potentially livelihood, local environmental damage and disruption of local social structures for example through a workforce influx and health impacts. Whilst there are examples of transparent reporting in this area, through case studies and indicators such as numbers of complaints made, impacts of corporate activities on these ‘fenceline’ communities, either inherited or otherwise, are not always clear when reading SD reports.

Business ethics

Business ethics is a relatively new area for reporting. Corporate scandals and new legislation in the USA and the UK has led to a small number of companies reporting business ethics management and performance: four companies reported quantitatively on whistle blowing and anti-corruption; an additional 6 reported qualitatively in these areas; and six companies reported on their relations with governments. The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative supports such transparency in relation to monies paid to governments and government-linked entities7. An under reported activity, and one that may well be a future area of focus for large companies in particular, are lobbying practices. Specifically, what role companies take in shaping government positions and policy across the SD agenda, and whether a company’s public statements reflect their lobbying position. Many organisations are currently reviewing their business ethics compliance processes and therefore it is likely that there will be increased reporting in this area over time.

Adding credibility through assurance

Out of the 36 SD mining reports we analysed, we found that 38% had sought formal third party assurance on selected information8.

The statements we looked at varied considerably in the scope of assurance, approach and methodologies used, and the language applied to describe the auditors’ assurance conclusions. This variety is an expression of the emerging state of the practice and the variety of organisations delivering assurance services. The two main assurance standards used were the International Standard on Assurance Engagements 3000 (ISAE 3000) and the AccountAbility 1000 Assurance Standard (AA1000 AS)9. With regards to the topics selected for assurance, a clear majority relates to SD performance data, particularly environmental, health & safety data. In addition, and increasingly, companies were keen to demonstrate the quality of their SD management and reporting, some by seeking third party confirmation of their compliance against established standards such as the AA1000 AS, the Global Reporting Initiative or local mining industry SD charters.

SD assurance will evolve significantly over the coming years: external opinion formers’ expectations will become more sophisticated, assurance conclusions will become part of the ingredients required for trustworthy communication, and new and better assurance standards will emerge. In that context, we believe that companies will seek to focus the scope of assurance on the SD issues that matter, and gain assurance from credible providers competent across the spectrum of their SD issues, and who deliver their work in accordance with known and sound assurance standards.

Why not all companies are reporting

Whilst reporting naturally has a cost, most companies see it as both a necessity and a benefit. However, like most other sectors, it is the smaller companies that do not report, or are reporting in a limited way. There could be a number of reasons for this including:

- little external pressure from stakeholders (in particular investors) to report;

- reflection of the general level of SD reporting dependent on the geography of mine locations (ie, less reporting in South America and Asia);

- cost implications of reporting; and

- a view that SD risks are not significant for investors and that they are difficult to assess and integrate into investment criteria.

Public reporting can be a driver for change. The discipline of gathering performance information that management are confident in publishing, and the practice of publishing and reporting progress against objectives and targets can inspire performance improvement. Frequently the publication of SD performance triggers internal change where acceptable standards are not being met. However, publication can also lead to external pressures, a factor that might put some companies off. Whether a company needs to report more or less on its SD performance is a question for relevant stakeholders. Good practice is at least to report on those SD areas that pose a risk to the performance of the business, which by default are likely to be the most significant SD issues to key stakeholder groups.

So why report?

If a company believes that its approach to sustainable development is important, then the likelihood is that other key stakeholders will also be interested. Sustainable development reporting is a key part of communication of SD management.

The generation of trust

Trust has been a critical issue for many companies and none more so than in the mining sector. The concept of licence to operate is built on the appropriate behaviour of a company, and the trust that is built up over time facilitating both current operations and future developments. A great number of individuals are watching and commenting on mining operations and developments, from local populations to non-governmental organisations and governments, and the media. In addition, employees want to know that they are working for a company that understands and manages its nonfinancial performance well. SD reporting has been a key element for many companies in being open and honest regarding practices in those areas that impact stakeholders and the surrounding environment.

Responding to investors

For large mining companies, confidence gained through the SD report and face to face discussions with investors and analysts regarding SD management supports investment decision making. There has been some research into the link between SD performance and financial performance, and a correlation is difficult to identify. That said, a focus on SD does not harm investment return, and anecdotal evidence suggests that good management in these areas is considered a proxy for good management more generally. SD and corporate governance issues were recently cited as the most important non-financial factors considered by mainstream investors10. In addition, we are increasingly seeing the inclusion of social and environmental risk screening. The Equator Principles11, for example, provide criteria for capital project financing and have been adopted by more than 35 global financial institutions who have agreed to withhold funding from projects that do not meet the principles’ standards. Within the newly refined principles effective from July 2006, the threshold of projects to be considered has been lowered from US$ 50m to US$ 10m.

However, the lack of SD information for smaller mining companies does not seem to limit access to capital. This may be explained by the view that SD risks are not significant for certain investors, are difficult to assess and integrate into company analysis, or that there is greater acceptance of risk in certain investment decisions. It should be pointed out however, that there has been a rapid expansion in the seriousness given to SD issues, and in five or ten years time this may well be a different story.

Managing risk

Companies need to have appropriate risk management processes that include SD risks and manage SD performance to ensure business survival. For most, this includes reporting SD in an open and considered manner. Companies with this bedrock are in a better position to manage issues as they arise and not be caught out by risk factors that have not been fully considered.

Demonstrating leadership

The drive to be a leader in SD has been key for some organisations who use the position proactively to enhance their status as a "good corporate citizen". Mines are frequently significant employers in an area, and companies benefit from the ability to communicate as a local leader, in addition to demonstrating good management and performance on the international stage.

Is it in or out?

What to report is an evolving debate, but has been clarified in recent years by the GRI work including the sector specific guidance. In volume terms, the number of pages in SD reports has grown along with the number of subject areas reported within the SD arena.

Recent discussion on business risk and a focus on what is ‘material’ to a company have led to a reanalysis of SD issues, and, whilst frequently increasing the list of issues to be covered, has also provided frameworks for prioritisation.

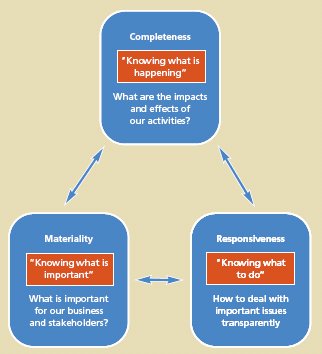

Leaders in the field now articulate why managing and reporting SD is important to their business and understand that SD issues impact on business performance and create business value, as illustrated in the diagram below12.

Over the coming years, the reporting of SD practices will continue to become more sophisticated, driven by both leaders in the field and their linkage of SD issues to business performance, as well as by increasing regulatory requirements.

Summary and conclusions

SD reporting has come a long way, reflecting the challenges and changes in SD management within organisations. Whilst legal requirements, particularly for some environmental issues, exist in a few countries, voluntary SD reporting is becoming the widespread. Despite agreement through the mining supplement of the GRI, there is a diversity of reporting approaches, from extensive public reporting through limited to no public reporting.

For those companies that collect large volumes of data and information, the pressure is to be able to clearly demonstrate good SD performance, rather than just extensive reporting. For those companies that do not report it may be construed that SD related information is either not available to directors, or is not effectively managed, thereby leaving companies exposed to a range of business risks.

The mining sector is still impacted with adverse perceptions and realities due to conflicts with stakeholders over land use, environmental damage, corruption, unionisation, the spread of HIV/AIDS and increased concern over resource scarcity.

In addition, awareness of SD issues will grow exponentially, frequently linked to perceptions of social justice, as demonstrated by the rapid growth of concern and action related to climate change. The use of SD information by stakeholders in their interactions with companies will also inevitably change, demonstrated by the use of SD criteria by the financial institutions. Companies should be prepared for such challenges.

The size of an organisation may influence the scale and nature of reporting. However, reporting can be an effective tool not only for external communication, but also for driving internal improvement through, for example, the processes of analysing and prioritising issues and reviewing and improving performance. Transparency brings challenges, but also pushes forward improvement. As such reporting itself should be seen as an important element in the development of sound SD management.

Those companies that have established SD management and reporting processes have focused on raising internal awareness, have been engaging with external stakeholders regarding SD performance and have enhanced governance processes. Companies that now have a strong base are building on this, taking steps to generate further value from SD management. Reporting is part of this, used as one of the tools to maintain trust with key stakeholders, tailored to specific needs such as local markets and specified stakeholders.

Recommendations

We would recommend that companies continue to develop SD management practices as the main driver to improve SD reporting through:

- integrating corporate responsibility practices into the organisation’s day to day operations by establishing and realising agreed values and performance;

- aligning corporate responsibility practices with the organisation’s value drivers to maximise benefit to all stakeholders;

- driving performance through challenging objectives and target setting;

- demonstrating stakeholder responsiveness at global and local levels; and

- enhancing effectiveness, reliability and trust of reported and management information through independent assurance.

The SD management and reporting practice underlying these principles can drive a mining company to identify its social and environmental impacts (completeness/awareness), know what is important (evaluation of materiality/relevance) and, enable it to know how to respond in a meaningful and transparent way. This should lead to better managed mining companies delivering better business performance and shareholder returns, and should lead to much improved SD reporting focused on SD issues and performance that really matter.

Using the AA1000 principles of ‘Completeness’, ‘Materiality’ and ‘Responsiveness’, as illustrated below, can be a meaningful way to achieve better SD management and reporting:

Appendix 1

Publicly available SD information for the following companies have been analysed as part of the research for this paper:

Alrosa Co. Ltd.

Anglo American plc

Anglo American Platinum Corporation

Antofagasta plc

Anglogold Ashanti Ltd.

Barrick Gold Corporation

BHP Billiton plc

Celtic Resources Holdings plc

Companhia Vale do Rio Doce (CVRD)

Corporancion Nacional del Cobre de Chile (CODELCO)

Falconbridge (acquired Nov 2006 by Xstrata plc)

Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold Inc.

Hambledon Mining plc

Harmony Gold Mining Company Ltd.

Glencore International AG

Gold Fields Ltd.

Impala Platinum Holdings Ltd. (Implats)

Inco Ltd. (acquired Jan 2007 by CVRD)

Kazakhmys plc

Kenmare Resources plc

Kumba Resources Ltd.

Lonmin plc

Newmont Mining Corporation

Noranda Inc. (acquired by Falconbridge in 2005)

Mining and Metallurgical Company Norilsk Nickel

Peter Hambro Mining plc

Phelps Dodge Corporation

Placer Dome Inc. (acquired by Barrick in 2005)

Randgold Resources

Rio Tinto plc

SUAL Group

Sumitomo Metal Mining Co. Ltd.

Teck Cominco Ltd.

Vedanta Resources plc

Xstrata plc

The above list of companies analysed is not intended to be exhaustive and was selected to give a representation of companies of different sizes and operating in different areas of the world.

Classification of large, medium and small was based on the following market capitalisations:

Large: Over US$ 5b

Medium: US$ 860m to 5b

Small: Up to US$ 860m

Footnotes

1 CorporateRegister.com

2 ‘Tomorrows Value: The Global Reporters 2006 survey of Corporate Sustainability Reporting’, United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), Sustainability and Standard & Poor, 2006.

3 Research is based on information available on company websites. Those companies reporting in both their annual report and accounts and with a stand alone report are just noted here as having a standalone report. 4 In most cases where quantitative data exists, qualitative information also exists including policies, management systems and case studies.

5 As per GRI’s ‘Sustainability Context’ reporting principle.

6 Ceres ‘2006 Corporate Governance and Climate Change: Making the Connection’. Ceres is a US based network of investors, environmental organisations and other public interest groups.

7 For further information see http://www.eitransparency.org/

8 To provide some context to our mining sector analysis, across all sectors, 62% of the Top 100 European companies and 3% of the Top 100 USA companies sought some kind of third party assurance in 2006.

9 For further information regarding AA1000 AS see:

http://www.accountability21.net/10 Mercer Investment Consulting, ‘Perspectives on Responsible Investment: A Survey of US Pension Plans, Foundations and Endowments and Other Long-Term Savings Pools’, January 2006.

11 The Equator Principles are a banking industry framework for addressing environmental and social risks in project financing. Financial institutions adopt the principles, then put in place policies, procedures and processes, and report publicly regarding their implementation experience.

12 Diagram built on Deloitte’s ‘Enterprise Value Map’ methodology, which can be used to map and analyse in detail how SD issues affect value generation. Strengthen corporate reputation

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.