Since our report on Hoyland v Asda Stores Limited (2005) in the July 2005 edition of the Employment Law review, there have been some changes to the Sex Discrimination Act (SDA) and the Equal Pay Act (EPA) which may impact on the amount of bonus that an employee is entitled to receive.

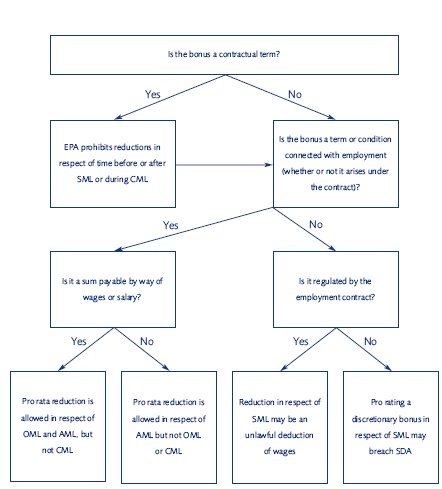

The payment of bonuses in respect of periods of maternity leave has long been a contentious issue. We summarise below - and illustrate in the diagram on page eight - how employers should approach the amount of bonus to be awarded to employees who have taken maternity leave during the relevant period.

Is the bonus contractual? If so, OK to pro-rate performance-related bonus in light of maternity leave

The starting point is to decide whether the bonus is contractual. If it is, section 1(e) of the EPA prohibits reductions in respect of time before or after statutory maternity leave, and in respect of the two-week period of compulsory maternity leave (CML), but does not preclude pro-rating in respect of time during which an employee was actually on maternity leave.

Employers should be mindful of cases such as Horkulak v Cantor Fitzgerald (2004), where it was held that a bonus which was stated to be discretionary was in fact contractual where it was part of the employee’s remuneration structure.

Is the bonus "regulated by the contract?" If so, OK to pro-rate performance-related bonus in light of maternity leave

The EAT stated in the Asda case that complaints excluded by section 6(6) of the SDA as being complaints about "benefits consisting of the payment of money when the provision of those benefits is regulated by the woman’s contract of employment" are, like contractual bonuses, covered by the EPA. Further, the Scottish Court of Session held in this case that this phrase was so wide as to include a bonus which "but for the existence of the contract of employment … would not be paid". Therefore, it seems that the EPA prohibitions on reductions in respect of time before or after statutory maternity leave, and in respect of CML, could conceivably apply to all sorts of noncontractual and even discretionary bonuses too, in spite of the reference in the EPA to contractual terms.

Is the bonus a term or condition connected with employment?

If so, OK to pro-rate performance-related bonus in light of AML, and, if "wages or salary", also for OML Whether or not the bonus is contractual, or regulated by the contract, section 75(1)(b) of the Employment Rights Act 1996 (ERA) and Regulation 9 of the Maternity and Parental Leave Regulations 1999 (MPL Regs) prohibit pro-rating a bonus which is a "term or condition connected with employment" in respect of CML.

During additional maternity leave (AML) section 73(5) ERA provides that the right to remuneration does not continue, so prorating a bonus (remuneration) to exclude time during which an employee is on AML will not fall foul of the ERA. During ordinary maternity leave (OML), section 71(5)(b) ERA also provides that the right to remuneration does not continue. However, this time remuneration is defined under regulation 9 of the MPL Regs as "sums payable by way of wages or salary", so pro-rating a bonus to exclude time during which an employee is on OML will only be within the ERA if such a bonus can be classed as wages or salary. If it cannot, it should be paid in full.

Is the bonus "wages or salary"?

In the Asda case, the EAT held that, where a bonus was paid in recognition of work undertaken by an employee and it was paid through the employer’s payroll and was subject to tax and national insurance contributions as well as being pensionable, it could be classed as wages or salary.

Is the bonus discretionary? If so, risk facing successful sex discrimination claim if pro-rate a bonus which is not "wages or salary" or "regulated by the contract"

Somewhat perversely, it is if the employer can, in its absolute discretion, unfettered by any rules, decide whether to award a bonus and if so how much, that an employee may nevertheless be able to claim that pro-rating it in light of maternity leave was discriminatory.

Section 3A(1)(b) SDA provides that an employer discriminates against an employee if he treats her less favourably than he would otherwise have done on the grounds that she is exercising her rights to maternity leave. As stated above, no complaint can be brought under the SDA in relation to "benefits consisting of the payment of money when the provision of those benefits is regulated by the woman’s contract of employment" (section 6(6) SDA). There are conflicting decisions on whether pro-rating a discretionary non-contractual bonus in light of maternity leave would amount to sex discrimination.

In GUS Home Shopping Ltd v Green & McLaughlin (2000), the EAT held that it was discriminatory to reduce a discretionary loyalty bonus on the grounds that a woman was on maternity leave. However, in Lewen v Denda (2000), the ECJ held that an employer may pro-rate a Christmas bonus to exclude time during which an employee was on maternity leave, as long as it made a payment in respect of work done and in respect of any time during which the woman was prohibited from working. This decision is in line with the Gillespie case in which the ECJ held that a woman on maternity leave was in a special position, not comparable with a man or a woman actually at work, and therefore she could not claim equal pay with a man or woman actually at work.

It remains to be seen which of these decisions will be followed in future but, for the time being, employers should be alive to the risk that if they do not pay a discretionary bonus in full to someone who is or was on maternity leave, they may face a sex discrimination claim in respect of the shortfall.

Conclusion

The only way an employer can be legally sure that pro-rating bonuses to reflect absence due to OML and AML cannot be challenged under the legislation outlined above, is to make its bonus scheme contractual and to ensure that bonuses are part of each employees' wages or salary. Inflexibility of this sort in its bonus arrangements may be precisely what it wishes to avoid for other reasons and the employer will need to decide which goal is its priority. Many employers come up with what feels like a fair method of pro-ration and are then prepared to take the risk of maternity-related claims.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.