The UK buy-to-let mortgage market has boomed in recent years – a fact that has been well documented both in the press and by the industry itself.

A number of niche mortgage markets have witnessed strong growth over the past few years, with the buy-to-let market proving to be the fastest growing niche sector.

Overview

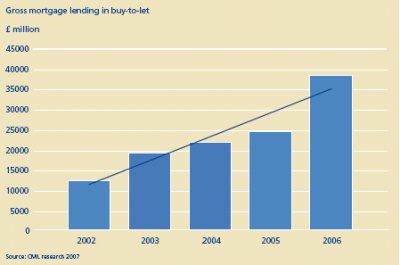

In fact, the UK buy-to-let mortgage market has outperformed the UK total secured lending market with an average annual growth rate of 45.7% (compared to the average growth rate for the market of 17.9%) over the last 7 years. As a result the buy-to-let market was worth £38.4 billion by the end of 2006.

The growth in 2006 was particularly driven by demand from non-professionals, following a more subdued performance in the second half of 2004 and early 2005.

|

Statistics

|

This was as a result of confidence returning to the market, as arrears levels continued to fall (3 months + arrears 2005 0.59%) (2004: 0.66%).

At the same time, lenders increased their risk appetite extending on average the maximum loan to value (LTV) from approximately 80% to 85% and reducing minimal rental cover from approximately 130% to 120%.

In addition, Housing Price Index (HPI) continued to reduce the number of first time buyers who could afford to buy – particularly in the South East. This was exacerbated through high immigration levels and the increased student population which continued to bolster the need for rental property.

Major players

The major buy-to-let lenders in the UK are listed below:

|

2006 (H2) |

2004 |

|

|

1 |

Birmingham Midshires |

Birmingham Midshires |

|

2 |

Mortgage Express |

Mortgage Express |

|

3 |

Paragon Group |

Mortgage Business |

|

4 |

GMAC |

NatWest |

|

5 |

Bank of Scotland |

Paragon Group |

|

6 |

Northern Rock |

Northern Rock |

|

7 |

The Mortgage Business |

GMAC-RFC |

|

8 |

West Bromwich Building Society |

Capital Home Loans |

|

9 |

UCB Homeloans |

Bristol & West |

|

10 |

Capital Homeloans |

Platform |

|

Source: CML research 2007 |

||

As can be seen, the only building societies presently in the top 10 are West Bromwich, and UCB a subsidiary of Nationwide.

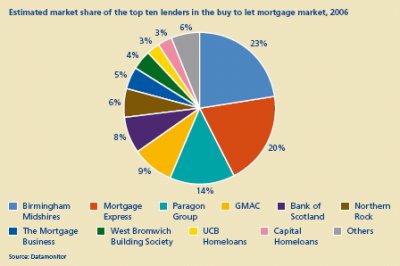

In fact, the buy-to-let mortgage market is dominated by specialist lenders. Birmingham Midshires leads the way with an estimated share of 23%, followed by Mortgage Express with 20% share of the total value of new loans realised in 2006.

Overall, HBOS is the only banking group with more than one subsidiary in the top ten. Through its various brands, Birmingham Midshires, Bank of Scotland and Mortgage Business and BOS, based on our estimates, HBOS held a combined share in the order of 37% of buy-to-let gross advances.

Below we have included an estimate of the market share held by the top ten players in terms of gross advances. This shows that the top ten players in the market occupy an estimated 94% of this niche sector in terms of gross advances in 2006.

Key considerations

It is clear that the buy-to-let market is significant and is here to stay. Though recent interest rate changes both directly and via the longer term effect on HPI, will probably reduce the rate of growth, this market will remain significant.

On this premise, building societies will need to consider whether they should enter or expand their presence in this market place.

We have therefore outlined some of the considerations that management will need to address if they were to enter or expand their presence in this market.

Customer acquisition

In an increasingly competitive buy-to-let mortgage market, various strategies should be considered by building societies to acquire buy-to-let customers:

- Targeting selected customer groups;

- Offering a wider product range;

- Pricing strategies;

- Offering a higher quality service/support to intermediaries;

- Provision of additional services to wealthy investors.

Building societies need to consider which strategy to adopt and build their customer service seamlessly around the model adopted.

In addition, they need to assess which segment of the market that they need to enter - the professional buy-to-let investor or the more amateur customer. The majority of lenders have to date, concentrated on the professional landlord customer group, however, some lenders, such as UCB HomeLoans (and to some extent West Bromwich Building Society) have targeted small buy-to-let investors.

Intermediaries

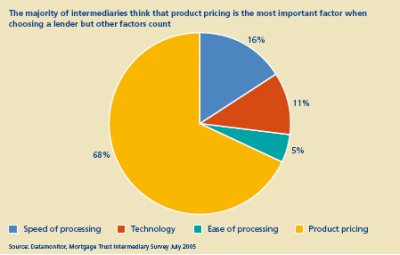

Intermediaries play an important role in the buy-to-let mortgage market. An estimated 70% of buy-to-let gross advances are generated through intermediaries.

Societies who enter this market, will need to assess how they interface with intermediaries, and whether they can rely on gaining market share just through more direct channels.

Making the life of intermediaries easier has a positive effect on a lender’s share of the intermediary channel, and therefore societies may choose to focus on providing a seamless and effective service for their intermediaries.

The importance of intermediaries in the market has been illustrated by Edeus – where existing relationships with intermediaries have been exploited by the management team.

The cost of bad debts

The buy-to-let market is still in its early stages. However, to date the market continues to grow and arrears statistics continue to outperform the mainstream market.

In fact, in the industry there is the common assertion that there are two repayment vehicles – the rental income and the landlord, and so therefore this lending is more secure.

The FSA and others are more sceptical and believe that there may be problems of "moral hazard" as the borrower does not have to keep the "roof over their heads".

Overall, the jury is out as the underlying trend in arrears is still hidden, given that there has not been a significant down turn in HPI. In addition, the criteria on which loans are offered have been periodically increased – allowing potential customers who are in difficulty some room to re-mortgage and gear up out of difficulty.

In this context building societies will need to assess their risk appetite, their view on future bad and doubtful debts, and provide accordingly.

Terms and conditions

Lenders have been allowing maximum LTV’s offered in the market to be increased from 80% to 85%. In addition, rental cover may now be as low as 106% of mortgage interest at the aggressive end, though normally the cover requirement is still 120%. However, this is still down from the 130% level previously required.

Societies will need to develop their underwriting criteria in this context.

Managing the portfolio

The CML defines professional landlords as those who receive rental income equal to at least the national average income, and who live off their income without selling properties to realise capital gains.

The CML also states that under this definition, professional landlords, have a portfolio worth at least £1 million, have been landlords for at least two years and have portfolios of between 6 and 20 properties compared to an average of two properties for non-professionals. Societies would be encouraged to divide their clients between these two categories and manage their exposure in this way, as the credit management framework required for professional landlords is more akin to commercial lending, requiring new risk measures and management information.

Credit risk assessment and pricing for risk

Whilst there are several lenders, both mainstream and niche lenders, operating in the buy-to-let market the basis on which credit risk is assessed varies greatly.

Based on our experience mainstream lenders attempt to adopt existing scorecards for buy-to-let lending with some success, albeit this has not really been stressed for a dramatic downturn in the market.

Niche players have more flexibility and criteria in their scorecards; however, the sophistication of pricing for risk and knowledge of the buy-to-let sector is not always apparent. These lenders typically build in high margins and move down the risk curve rather than competing on price. Given their warehouse line/securitisation funding structures and the benign market, the risk for these companies is mitigated by the returns as they manage away the consequences of seasoning effects on their balance sheets.

Where there are dedicated buy-to-let scorecards, these are based upon data from the US. This will change as firms own portfolios begin to season (with much lower default rates than initially anticipated), but a question nedds to be asked as to the relevance of this data.

Against this background, societies will need to assess how they price risk appropriately.

Conclusion

It is clear that the buy-to-let market is significant and is here to stay.

Though recent interest rate changes and their effect on HPI will probably reduce the rate of growth, this market will remain significant.

Building societies will therefore need to actively consider whether they should enter or expand their presence in this market place, based on whether it is aligned with their risk appetite.

The Mortgage Advice Process

It has been a little over two years since the sale of Mortgages became regulated by the Financial Services Authority (FSA). The objectives of the move to regulate the area of the industry were in line with the FSA’s agenda to provide protection to the consumer and to secure a fair deal for the mortgage buyer. This compulsory regulation has brought with it a significant change in the way that the industry operates, and a challenge for firms in meeting the regulator’s requirements.

These requirements appear on two levels. Firstly at the principles level; these principles bind all regulated firms irrespective of size or complexity. Providers are bound to operate with integrity and assure the fair treatment of all customers.

On the second level come detailed rules which firms must adhere to, around the quality of advice and around key documentation which must be provided to customers. Specific guidelines have also been introduced around the setting of fair fees with particular emphasis on exit fees.

A key theme in all of these changes has been around improving consumer understanding, both through clearer documentation and through providing clearer advice so that customers can understand what they are buying.

At the heart of all of this is the ultimate aim of levelling out the previously somewhat confusing world of mortgage arrangement. As all firms must now comply with these principles and rules the aim was to encourage consistency amongst firms and to simplify the process of shopping around for the customer, who could compare price and service at a glance.

So after a bedding in period of over two years, are all firms equal? Recent findings published by the FSA suggest not. The regulator published a letter on January 8th this year which focused on findings from a survey of 252 firms.

Is it a case of the big "fat cat" firms being unfair to the consumer? Again the recent studies suggest perhaps not. Failure to meet standards was predominantly found in the small firms sector, or with the ‘one man bands’. These firms were the most likely to have omitted to have proper procedures in place, and consequently they are more likely to fail to give good advice in accordance with the requirements.

This is not to say that building societies may rest on their laurels. Findings also revealed that whilst they have effectively developed processes and systems to implement the requirements, mystery shopping has highlighted that procedures are not always followed by staff.

So what does this mean for firms on the whole? Specific concerns lie around consumers being encouraged to borrow more than they can afford. The regulator’s Managing Director, Clive Briault went so far as to say that in many firms the "poor processes increase the risk of unsuitable advice being given"; a damning statement for providers who have had over two years to get to grips with the current requirements.

With key concerns around the failure to understand what a customer can and cannot afford it will be wise for firms to review their multiples evaluations and their affordability assessments. In addition to this the requirements to improve record keeping will keep the IT teams busy on an ongoing basis.

The most recent message seems to be a clear one; much work has been done but there is so more to do if firms are to avoid the planned regulatory censure.

Taxation Developments On Securitisation

Securitisation as a whole, and specifically the securitisation of mortgage loans, is an increasingly popular means of raising finance. Significant developments in the corporation tax treatment of securitisation companies are expected to provide a further boost to undertaking securitisations using a UK Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) for both UK and overseas originators. In addition, there have been a number of recent VAT cases that have in some respects clarified the VAT treatment of the SPV but also raised issues for further thought.

A summary analysis of the key developments in both corporation tax and VAT on securitisation is set out below. These issues should be given careful consideration both by building societies that already have well developed securitisation programmes and those considering securitisation for the first time.

Corporation tax and securitisation

One of the key economic drivers behind securitisation is that finance can be raised at a lower cost than would otherwise be possible; this is achieved through the use of an SPV with an enhanced credit rating. In order to obtain an enhanced credit rating, there should be the greatest certainty of flows in and out of the SPV as possible, with taxation being one of these flows.

The introduction of new accounting standards regarding the accounting for debt and derivatives under both International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and UK GAAP caused a particular issue for UK SPVs as it threatened to make the accounting profit too volatile to be an acceptable basis for computing cash tax liabilities.

Interim measure

The UK tax authorities, as a result of extensive lobbying, responded to the issue in an effective manner by introducing a temporary regime whereby securitisation companies continue to base their tax calculations on accounting profits determined under ‘old’ UK GAAP (i.e. pre FRS 26). In effect, retaining the previous status quo.

However, it was always recognised that the preservation of ‘old’ UK GAAP for tax purposes was a temporary measure and provision was left for new regulations to be implemented.

The date to which the ‘old’ UK GAAP rules can apply has been previously extended to accounting periods ending before 1 January 2008, and provision was made in the recent budget for this to be extended to a later (unspecified) date.

Securitisation Regulations

The new Securitisation Regulations, that have effect for periods of account beginning on or after 1 January 2007, resolve the issue on a more permanent basis by breaking the traditional link in the UK between accounting profits and taxable profits. In effect, the Securitisation Regulations tax a securitisation company in accordance with its retained cash, subject to commercially required cash reserves, as set out in the waterfall (the waterfall being the priority of payments in the SPV set out in the transaction documents).

The Regulations obviously needed to be carefully drafted to ensure that they will only catch those companies they are intended to catch and are sufficiently robust to prevent companies being artificially engineered to fall into the rules (i.e. for avoidance purposes). Experience to date suggests that, with the inevitable exceptions, these aims should be broadly achieved, particularly in relation to the securitisation of mortgages.

For existing SPVs it is noted that the transitional provisions have been extended such that it is uncertain when (if ever) SPVs that entered into a securitisation prior to 1 January 2007 will be obliged to apply the new Securitisation Regulations.

There are provisions to elect into the new regulations for such SPVs that meet the criteria, and, although to be assessed on a case-by-case basis, most SPVs are likely to want to elect in as the new regime is a favourable one. The time limit for the election is within 18 months of the end of the first accounting period beginning on or after 1 January 2007 and is irrevocable.

Where the Securitisation Regulations apply taxable profits are therefore comparatively certain and the SPV is only taxed on a small margin (typically the waterfall provides for a margin of just 0.01% of the principal of the balance outstanding on the Notes to remain in the SPV). Certain conditions must be met in order for the Securitisation Regulations to apply; two key issues being that, firstly, the SPV is a "securitisation company", and secondly, that the payments condition is met.

Securitisation company – there are a number of ways in which a company will be regarded as a "securitisation company" within the Securitisation Regulations, and accordingly a securitisation company is defined by means of a number of attributes. These require careful consideration when assessing potential securitisation structures, however in a traditional mortgage loan securitisation they should not be overly onerous to meet.

Payments condition – the payments condition aims to ensure that cashbox companies cannot be smuggled into the regime by requiring securitisation companies to pay out all their receipts within a given time period except to the extent that cash reserves are required for credit enhancement and similar purposes. In essence it is a revenue protection mechanism for HMRC as the flows out of the SPV should be taxable in the hands of a UK resident tax payer. However, again, in a vanilla securitisation structure this condition should also be met without difficulty.

Other practical issues encountered to date include the means of obtaining sufficient comfort for the rating agencies that the assets involved are "financial assets" (another condition of the regulations) and queries relating to stamp taxes on securitisation.

Clearance procedures

There are no specific clearance procedures or tax rulings available in respect of the Securitisation Regulations, however the more general clearance mechanism of a Code of Practice 10 (COP 10) application is worth consideration. On the one hand, it should be clear whether or not the conditions of the Securitisations Regulations will be met, however this is new legislation and as such structures rely on obtaining as much certainty as possible and all securitisation transactions come under very close legal scrutiny; a positive COP 10 could help prevent further queries arising at the implementation stage.

The new tax rules are a significant development for securitisation in the UK and are welcomed. Although implemented due to the introduction of IFRS, they also remove many other tax issues, such as those concerning the deductibility of interest, that have historically needed to be overcome in the UK. The Regulations do set out a number of conditions that must be met and to this extent require careful monitoring, however they do offer the degree of certainty that is so fundamental for a securitisation transaction to function properly.

VAT and securitisation

The purpose of this section is to highlight a few of developments that have taken place in recent months as a result of case law, which affect the treatment of VAT in relation to securitisation programmes. (It does not deal with the roles and responsibilities of the cash and administration managers, as currently, these appear to be unchallenged by HMRC, and the assumption is that the securitisation is of UK loans/mortgages/ receivables involving a UK originator and a UK SPV.)

(i) VAT Treatment of the Assignment of ‘loans’, receivables etc. by the originator.

The assumption here is that, as is typical with loan/mortgage securitisations, the loans/mortgages etc are transferred/ assigned to the SPV without the completion of the transfer of full legal title, that is, only the beneficial/economic benefit interest is legally transferred. Where this happens, the High Court’s ruling strongly suggest that there is no supply by the originator/assignor to the SPV, but is rather simply a precondition necessary for the securitisation to take place [MBNA Europe Bank Limited (2006)]. This means that there may now be no exempt supply to consider in relation to the cash paid to the assignor by the SPV and, as a result, any VAT incurred on costs will be residual. Given that most Societies have very low or ‘nil’ VAT recovery, the practical implication of this is that there is little change to the amount of VAT that the originator may reclaim.

(ii) Does the SPV act as a ‘factor’?

Prior to the MBNA decision, it was thought that the assignment either, was an exempt supply for VAT purposes or, might be made as part of a factoring arrangement where the SPV was a factor. This latter point has caused some debate on whether the SPV is acting as a ‘factor’. However, for a supply of factoring to occur, the person to whom the loans/debts/receivables are assigned must (a) do something for the seller/assignor and (b) charge the seller for doing it. In essence, a factor will typically charge the assignor for ‘debt collection’ services etc. and this is a VATable supply. However, the general view is that, in securitisations, the assignee does nothing for the assignor and does not charge any consideration for services; it merely acquires the right to the loan/debt/receivable.

This debate now appears to be resolved by the High Court. In its decision [MBNA paragraph 102] the Court refers to transactions which, like the assignment of receivables in the MBNA securitisation case, are not supplies for VAT purposes. One of these transactions is that of factoring and the assignment of debts to a factor. In this way, the Court clearly sees a difference between securitisation and factoring.

(iii) What else, for VAT purposes, does the SPV do?

If the SPV is not acting as a ‘factor’ and does not appear to be supplying anything to the assignor, what is it doing from a VAT perspective? The only other thing that the SPV will do is raise capital by issuing financial instruments, typically commercial paper, notes or bonds.

Following the ECJ ruling in Kretztechnik [Kretztechnik AG v Finanzamt Linz, Case 465/03], HMRC issued a Business Brief [Business Brief 21/05 – 23 November 2005], in which they state:

"The issue of other types of security, such as bonds, debentures or loan notes, should…be treated as non-supplies [for VAT purposes] when the purpose of the issue is to raise capital for the issuer’s business." Prior to this, the issue of bonds etc by an SPV in a securitisation was seen by HMRC as a supply for VAT purposes and, where the purchaser of the bond etc was located outside the EU, this gave the SPV a right of recovery of VAT incurred on costs relating to the non-EU element of its supplies.

As a result, where the above conditions apply, any input tax is, following the ECJ ruling above, now to be treated as ‘residual’ and can only be recovered if the SPV makes any supplies that will give it a right to reclaim any of the VAT it incurs.

The interesting point, from a VAT perspective, is that, if the SPV is doing nothing for the originator, for example, it is not acting as a factor, is it in ‘business’ for VAT purposes? If it isn’t, then HMRC may well see the issue of the notes, bonds etc by the SPV as a supply for VAT purposes. This would, presumably mean that it was in business, and it would now be able to register for VAT to recover any VAT relating to the issue of the notes, bonds etc to non-EU counterparties. It might also be a requirement that the SPV is not registered for VAT in order to protect its bankruptcy remote status; although, with correct management of any claim, this should not present a risk to the SPV.

The fact that the SPV cannot reclaim any VAT it incurs, underlines the importance of ensuring that ‘servicing’ fees etc are treated as exempt by any supplier.

Clearly, this is an area where there is need for clarification.

Securitisation is a complex area for VAT and there is still much more certainty needed in determining exactly what, for VAT purposes, happens in a securitisation.

"Certain conditions must be met in order for the Securitisation Regulations to apply; two key issues being that, firstly, the SPV is a "securitisation company", and secondly, that the payments condition is met."

Best Defence – Data Protection In A Digital Age

The buoyant housing market and profits of many firms in the UK mortgage market have been balanced by some negative headlines, often on the same day. The adverse publicity has come in many shapes and sizes, but one common factor has been the seemingly inefficient management of customer data. This forms part of the building societies’ data protection responsibilities, and it is causing a number of potential issues.

Data protection is an area where regulation and reputational risk coincide. The regulatory framework is built on the 1995 European Data Protection Directive and the subsequent Data Protection Act 1998 (‘DPA'). There is a UK regulator – the Information Commissioner – and a range of rules around the processing of personal data (being any data relating to a living individual).

The regulations include rules on disclosures to individuals when collecting their data, maintaining the integrity of the data, allowing access to the information and moving the data overseas. Over time the Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) has generated further guidance, and has become increasingly proactive in promoting and enforcing its regime.

Building societies have always been at the forefront of data protection, as they handle a lot of personal data which is highly important to the individual. FSA principles and regulation (e.g. Financial Promotions, Treating Customers Fairly) overlap with the Data Protection Act 1998 in this respect, and one would expect societies to set the standard for data protection.

However the trickle of data protection issues the banks and building societies have managed over the years has turned into a flood, with the older issues – call centre fraud, branch security breaches, etc – mixing with the new (laptop thefts, mortgage and current account charge complaints).

In February 2007 a major building society was fined £980k for failing to have effective systems and controls to manage its information security risks. The failings came to light following the theft of a laptop from an employee's home in 2006. The FSA investigated when it transpired that the building society was not aware that the laptop contained confidential customer data, and did not start an investigation until three weeks after the theft. It is worth noting that there was no customer detriment proven in this case – the fine was purely in respect of the perceived control failures.

On 12 March 2007 the ICO named eleven banks and financial institutions for an ‘unacceptable data protection breach’. This followed an investigation by the BBC programme Watchdog where a team searched rubbish bags containing confidential information from outside branches, finding customer details including a £500k transfer and a detailed loan application. The ICO required each bank to sign a formal undertaking to comply with the principles of the DPA, and then controversially posted the letters on their website. Most of the letters were signed by the CEO of that institution.

On 29 March 2007 the OFT announced a formal investigation into the fairness of current account charges, to be completed by the end of the year. Over the past year the campaign against current account charges has gained momentum. Under the Data Protection Act 1998, people have a right to ask an organisation for a copy of their personal data – a ‘subject access request’ – for a maximum fee of £10.

"Building societies have always been at the forefront of data protection, as they handle a lot of personal data which is highly important to the individual."

The first action recommended by the campaign sites is to request a copy of the last six years’ statements, to provide the material to then submit a complaint about any charges. The result is that the data protection function is the first point of contact for challenges on customers’ charges, and the volume of requests for a number of firm’s has grown, from tens in a year to hundreds in a week. The OFT decision disappointed firms hoping for clarity on the complaints issue before the end of the year, and has condemned data protection teams to another nine months of the status quo. From these examples a number of themes are apparent. Building Societies face:

- Challenges in knowing where their customer data is, what they actually hold, and how to manage access to it;

- The need to maintain appropriate standards – in areas such as staff training, security, policy and procedures – whether the operations are in a call centre, a branch, or head office;

- Challenges in reacting quickly to initiatives from the press, regulators or customers on their stewardship of the data; and

- Increasingly active regulators, who are looking to change behaviour through fines or reputational damage.

The net result is a widespread public perception, whether justified or not, that banks and building societies are not always satisfactory custodians of their customer data, which is reinforced with each report on a new data protection breach.

However, there is also an operational impact on the building societies. All the issues discussed here will have involved the data protection team in each building society, and collectively there has been a very real strain on the teams involved.

The volume of subject access requests has led in some instances to significant use of contractors and reassigned resource. Actions by the ICO have placed the Board’s spotlight on the Data Protection Officer. For the data protection teams there is little notion of business as usual any more, their risk-driven, measured, data protection compliance programmes have been replaced more often than not by fire fighting and crisis management.

In the short term firm’s are, quite rightly, addressing each issue individually. At the same time there is a realisation that their actual or perceived management of customer data has to evolve, to avoid breaches and rebuild consumer trust. The solution will involve the integration of regulatory compliance, security and risk management, with an understanding of how good customer data protection can help build the retail brand. The rewards for successful building societies could be substantial, but by the same token failures are likely to become more costly.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.