In June 2017, we published our report ' Breaking the dependency cycle: Tackling health inequalities of vulnerable families' which explores how the social determinants of health, such as access to and opportunities in education, employment, housing, public transport and welfare services, influence health inequalities in Western European countries. Mette Lindgaard (our Global Social Services Lead) and Rebecca George (then Global Public Sector Healthcare Lead and now Public Sector UK Lead) provided support and direction for the research. This week's blog gives Mette's take on the report, and how she and her colleagues have used the research findings in discussions and debates with clients over the past few months since publication.

Addressing a global challenge

In early 2017, Rebecca George and I discussed identifying

a way to raise the profile of the challenges faced by countries in

tackling health inequalities and the role and inter-relationships

of the health and social service providers charged with addressing

these challenges. Our aim was to find a novel way of

'connecting the dots' between the two sectors to support

our clients, as well as improve the understanding of our teams who

work across these two sectors. We were also aware that while there

have been marked improvements in life expectancy, all developed

countries with mature health care systems experience varying levels

of in-country health inequalities; with excess mortality and

reductions in healthy life years closely correlated to regional

deprivation. We therefore asked the UK Centre for Health Solutions

to develop a research project that would examine the challenges

faced across Western Europe in a novel and compelling way and

identify examples of good practice that could be applied more

widely.

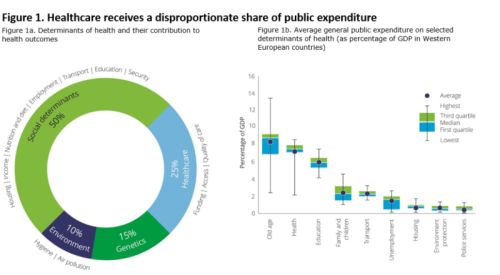

The report produced by the UK Centre for Health Solutions does a great job of communicating the interconnectivity between different sectors of public services in an easily identifiable and intuitive way. In my opinion, the most impactful chart from the report, and the one which I have since used in many conversations, is Figure 1 (see below). It demonstrates, at a glance, how operating in silos fails to address issues of health inequalities. Despite healthcare contributing to only 25 per cent of health outcomes, all countries across Europe disproportionately invest in healthcare services; meanwhile the social determinants of health contribute to half of overall outcomes.

Source: Deloitte Centre for Health Solutions, 2017; Eurostat, 2015

While I know from previous discussions with public sector leaders across the World that they are well aware of the impact of the social determinants of health, they also acknowledge that they have struggled to act on this knowledge in a sustainable way. The Centre's report has allowed me and my colleagues to engage with stakeholders in a new and constructive way. For example, we have used the life cycle approach (see below) as a framework to discuss and debate our respective views of the challenges and consider whether the examples of good practice that are highlighted in the report might help. These discussion have helped us to build new relationships and strengthen existing ones with interested parties from across the world, ranging from the police to social protection, justice, education and health. Indeed, we have received positive feedback from all stakeholders, particularly with regard to the way we organised the report around a set of personas that represent the different members of a 'typical vulnerable family', taking a unique life-cycle approach.

Figure 2. A life cycle approach to vulnerable families

Source: Deloitte Centre for Health Solutions, 2017

Developing a collaborative approach

Addressing health and social inequalities across the life

cycle remains one of the hardest challenges faced by most

countries, and analysing shared responsibilities can often be seen

as a threat to individual public sector organisations. However,

with this report we have succeeded in being both bold and

provocative, in challenging governments to look across silos in a

non-threatening way, and inviting all stakeholders to come together

and engage in constructive dialogue.

In all settings in which I have presented the report, its findings have been widely accepted, and have acted as a framework to drive new and truly collaborative conversations. The report is seen as having a constructive tone, and the life cycle approach has resonated with all sectors. I also find that focussing on one or more of the report's 16 case examples helps guide our discussions into contemplating actionable solutions.

The time for action is now

To date, the report has been used in presentations and meeting

across more than ten countries and regardless of the audience, it

is easy to make the case for interconnectivity and the need for

joint action between the health and social care sectors. Of course

such conversations have always happened but what feels different to

me this time is that policy makers appear to be paying closer

attention and want to change the status-quo. The research is

therefore serving not only as relevant background information for

interested parties, but also as a framework to support them in

exploring options for working more collaboratively. I plan to

continue using the report to continue to raise the profile of this

important issue and help stakeholders work together more

effectively to tackle the social determinants of health in order to

secure a healthy and sustainable future for everyone.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.