Views on the delivery challenge from senior civil servants recruited directly from the private sector

Foreword

Last year, Deloitte examined the Delivery Challenge for Government and highlighted 'strategy execution', better use of the private sector, moving from a culture of targets to one of engagement and reviving the public service ethos as particularly pressing issues. This year, we have interviewed around 50 people, who have moved from the private to the public sector, to find out how their perceptions can contribute to the delivery debate. We found that:

- The traditional model of SCS motivation and SCS quality still holds.

- The SCS imposes significant process burden on itself and manages to be simultaneously under-resourced and wasteful.

- Managing day-to-day performance continues to be a challenge and pay is part of the problem.

- The SCS has imported skills but commercial decision-making and cross-governmental working remain challenging.

This paper focuses mainly on an analysis of what the externally recruited SCS have told us. Our research also suggests a number of recommendations for public-sector organisations to apply lessons learned from the private sector. We would like to thank all the senior civil servants we interviewed for this report. Without the insight and perspectives they provided, it would not have been possible.

Executive summary

The SCS is under the microscope as public spending tightens and performance comes under critical scrutiny. Public spending has been increasing rapidly for some years, however the public doubts that outcomes are better. More challenges are cross departmental and this requires skills of collaboration and pace. Improving delivery continues therefore to be a key requirement for the SCS. It is often the case that people who come in to organisations from the outside have different views – based partly on comparison and partly because they haven't built up the organisational assumptions which inevitably happen over time. Earlier this year we carried out a survey of around 50 people who had joined the SCS recently from the private sector to find out, from their perspectives, how it is facing up to its delivery challenge.

The SCS is responsible for providing support to government ministers, developing and implementing government policy, and ensuring that services are delivered to citizens. The SCS is a group of around 3,500 professionals spanning 55 government departments and agencies across the country. They are the leadership team for nearly half a million civil servants. This enormous workforce constitutes many widely differing organisations including central departments, agencies and non-departmental public bodies (NDPBs).

The survey showed that:

- The traditional model of SCS motivation and SCS quality still holds.

- The SCS imposes significant process burden on itself and manages to be simultaneously under-resourced and wasteful.

- Managing day-to-day performance continues to be a challenge and pay is part of the problem.

- The SCS has imported skills but commercial decision-making and cross-governmental working remain very challenging.

This paper focuses mainly on an analysis of what externally recruited senior civil servants have told us. Our research also suggests a number of recommendations for public-sector organisations to apply lessons learned from the private sector.

The senior civil servants who joined from the private sector are as enthusiastic about what they do as those who have spent their entire career in the Civil Service. But they are not finding obvious avenues to express themselves. Some feel that they are not able to play to their own strengths, and others that they cannot properly achieve what they have been brought in to do. Many believe they will remain outsiders inside, and that their impact will always be limited.

Introduction: Asking senior civil servants if they can meet rising expectations

Rising citizen expectations, Comprehensive Spending Review financial settlements, the changing political cycle, and questioning value-for-public-spending, are all increasing pressure on the Civil Service. The leadership team, the SCS, is being challenged to deliver quality public services and value for money. A year ago we addressed four areas where we considered the SCS had to lift its game: policy-execution, organisation, using the private sector and leadership.1 This year we asked senior civil servants how they viewed the delivery challenge. We interviewed one perceptive subset: people who have joined the SCS from the private sector. This is a group of people who are increasingly important insiders, and whose previous experience enabled them to make independent comparisons. Their opinions and recommendations revealed the scale of the delivery challenge facing the SCS.

The SCS has been importing people from the private sector into various grades for years. Some have come into high-profile jobs such as the government CIO and Chairman of HMRC. Some have come in to run specific functions, sometimes because they have specifically relevant previous experience, for example, CFOs coming to run corporate services, and HR directors. People with general business management experience, running profit-and-loss accounts and implementing major programmes are recruited into a variety of roles, frequently to improve delivery capability and performance. SCS imports are recruited to be part of the service, one of the principal strategies to build SCS capability. They are separate from consultants and interim managers who, usually, come in to do specific tasks, transfer skills, then leave. It is hoped that imports will also transfer skills, bring new ways of working into the service, help to break down old traditions, and speed progress.

Direct private-sector entrants now account for 20 per cent of the SCS overall – with a higher proportion in the most senior grades. They are typically appointed at a premium to internal hires (and retain that premium through their careers), and on average are promoted more rapidly. They also depart more rapidly – SCS voluntary turnover is only 3 per cent per annum but external hires turn over at about twice that rate. So the questions are: Are external hires value-for-money? Are they delivering what they are being paid for? And is the higher turnover a concern given the cost of bringing these entrants in? Importantly, is traditional career development, including the fast-stream concept, still effective when the route to the SCS grades is shrinking? The probability of promotion from faststream entry through to SCS is less than 5 per cent.

Our interviewees were eager to talk to us and would appear to welcome more opportunities to share their thoughts. Every experience was individual but some powerful themes emerged.

Finding 1: The traditional model of SCS motivation and quality still holds

Motivations to move into the public sector varied widely. They included having an area of specialisation that enabled the move, having done all the roles in a particular profession except in the public sector, and that it was simply time to move, with the opportunity appearing at the right time. However, the over-riding motivator is impact. People wanted to be doing the most exciting and interesting work they could possibly do. They wanted to be giving something back either in the prime of their career, 'My mother asked me: What is your contribution to society?' or later on when they might have retired from other jobs. They are fascinated to be working in complex jobs with vast scale and in the heart of government.

The motivation was never money. All the people we interviewed, with the exception of those who came in on secondment, said that 'It wasn't the money!' Several had taken a 50 per cent cut in their compensation, and one secondee said that it would have been extremely difficult for him to take the job if he hadn't been able to stay on his company's terms and conditions.

Over and over again our interviewees said, 'it's interesting, really interesting', 'the breadth of work, complexity, and range', which 'directly impacts the lives of individual citizens'. They were enthused and highly motivated by the intellectual challenge and because they brought a skill set that was in short supply. They felt welcomed, on the whole, and valued for what they do. They have found a completely different environment, a flexible, tolerant and diverse culture in which they enjoyed working.

Private-sector recruits into the SCS all mentioned their public-sector colleagues, as 'motivated people', who feel a sense of 'pride and commitment' – who have chosen to be public servants. They talked about the importance of 'working with good, bright, dedicated people who genuinely care about the citizens and not the politics'.

And they talked about their own impact – the ability to make changes, influence direction at strategic levels, work with people who 'genuinely want to listen and learn', being a 'valued equal with people who are big important people – it's heady'. Those interviewees who had come in and attended Base Camp (a course offered for external recruits and people promoted into the SCS) within the first three months found it very helpful. Some, however, had not attended until they had been in their organisation for over a year, by which time the course had lost its impact.

Having an existing network or building one quickly was the most important factor in a successful transition. 'I am a relentless networker', said one. 'I had a network already and built on it', said another. 'I have an interest in the constitution and have been working with the Government from the outside and I had reasonable networks', was another comment. Having a guide, buddy and translator is also incredibly important. Using Base Camp and the Whitehall & Industry Group to build networks of people in other departments, particularly other people from the private sector, was a common message.

Joining a team with a clear role, in a context where the leadership clearly understands each individual's purpose, is another important factor in making a successful transition. 'They knew what they wanted and really probed before I started', was one comment. Another said 'they weren't woolly', and another, 'I had a senior management team who knew why I was there'. Recruitment processes varied widely but where they worked, they worked well.

There was also a theme of sitting back quietly, taking stock and not diving in too fast, which came up several times. 'I didn't throw myself around. You have to shut up and listen for a while to understand what the problem is'. Another said, 'changing jobs is like going on holiday – you are the visitor and you don't go in and try to force change'. Although people recruited from the private sector didn't meet as a specific group they did share a common view about themselves. 'There is a cohort of outsiders on the inside. I am not socialising with policy colleagues but people who have come in from outside', said one. Another said, 'we know we aren't going to have traditional civil service careers progressing to Director or Director General. It isn't about ability but the traditional route of developing in a department isn't going to happen to us. I am likely to have a nomadic civil service career'.

People who came in from the outside tended to fall into two types of role. Some went in to operational roles, often HR, Finance, IT or procurement. Others were recruited into delivery roles on major programmes. Although there were exceptions, most people tended to stay within the role area in which they were first recruited. So people who went into operational roles will move to other operational roles, and it is the same for people in delivery roles. Similarly, although it is difficult to generalise, the people going in to delivery roles tended to have come from service-based companies, often in the IT or consultancy sectors. They tend to have a strong sense of 'the customer', a service-based mentality that puts the customer first, worries about deadlines, is used to clarity, and is focused on outcomes. There was a suggestion that recruitment processes into the SCS could successfully consider the culture of previous organisations in matching people from the outside to SCS jobs.

The SCS has strong and effective capabilities and managing in times of crisis is right up there at the top, 'containment – management of the system – we have had war, foot and mouth, floods and we and the British public are still here and running the business in an orderly fashion'. Running the Government is a strong and core ability, 'there is a fantastic capability in running the Cabinet and getting minutes out, committees are run well. We do democratic government better than anyone'. Most of our interviewees mentioned the intellectual capability of the SCS, 'I see people who are intellectual highly capable, creative thinkers, who also have a kind of sixth sense of how to make things happen in this environment, which is extremely valuable'. Civil servants have 'gilded tongues – they are able quickly to assess a situation and come up with strategies to address it'. The Capability Review agenda has had a strong impact on the SCS, highlighting areas for improvement and giving departments focus.

Our interviewees believed that the capability of the Civil Service has improved over the last three years. This could be as a result of a combination of programmes in addition to the Capability Reviews – the professionalism agenda, external hiring, and a reduced number of targets. It is certainly visible to external observers that the quality of Finance, HR and IT has taken a leap forward since 2004.

|

Recommendations Where external recruits have had a buddy or a mentor they have appreciated it, and opportunities to meet and mix with people from their own and other departments have helped them adjust. Our research suggests that the practice of attending Base Camp and being assigned buddies or mentors should continue and be strengthened. Opportunities could also be created for externally recruited senior civil servants to join formalised networks, rather like the one which exists for non-executive directors. The progression rates from entry to promotion to the SCS have now changed with the mix of new entrants into senior roles. Our survey suggests that a different model of career development should be adopted from the faststream up, which intersperses operational, delivery and policy roles throughout careers. Private-sector (and international) experience is valued and should be encouraged, especially for top talent. People should be strongly encouraged to stay in their jobs for much longer, developing speciality skills and a track record of delivery. |

Finding 2: The SCS imposes significant process burden on itself

All the interviewees talked about process and the differences between the ways in which processes are managed in the public sector. 'The organisation is obsessed with process for process' sake rather than outcomes' and 'delivery is second to having a defendable process' were typical comments, repeated in many different ways throughout the interviews. 'Implementation is the publication of the paper', summarises the gap between policy formation and delivery of something tangible. Emails were often copied widely and diaries were filled with internal meetings which resulted in the comment, 'I could actually do nothing – and many people do'. The sheer volume of paper and number of words is also an inhibitor, 'I am apparently doing good work if I am preparing a paper'. For some, there was a lack of conception of the value of time – 'we will have developed an analytical method for thinking about climate change within the next five years, which is unhelpful when we are facing 2010 targets'.

The ex private-sector people found the pace slow, 'there's a lot of meetings, talking and process but not much focus on the outcomes of meetings, the actions'. One interviewee said, 'basic business principles and disciplines I have always taken for granted as a way of operating are simply not done'. They are told, 'we don't do it like that', or 'that's not the way'. 'The Civil Service is like a hermetically sealed system which hasn't changed at the same pace as the private sector'. For example risks are defined as things people don't understand rather than an essential and accepted business process. Getting simple things done can be frustrating too. Getting approval for anything is difficult, 'there is confusion about how and when things will be approved' and even then, 'you can go through all the approvals and things still don't work'. One interviewee sighed, 'all the rules and regulations. We repeat ourselves across government with different ways of doing the same thing. Processes make it incredibly hard, if you change one thing, you have to renegotiate if you want to do it again'. If you could find a decision maker the governance was poor and 'even when decisions are made there are no mechanisms to enforce them'. In particular 'it is hard to challenge the quality or value of a programme – if it has been through due process, then people do not challenge'.

The private sector started a long journey to streamline processes, simplify approvals, and develop professional capabilities throughout its organisations in the early 1990s. It was often motivated by burning platforms – they had to change to compete and stay in business. The burning platforms in the public sector are very different (foot and mouth or terrorist incidents, for example) and the public sector is good at understanding and managing them. It is harder for the public sector to undertake top-to-bottom systematic changes in processes, professionalism and ways of working. These sorts of programmes often require investment in order to make longer term savings – and they are hard to justify when there are so many other calls on budgets. Surprisingly, given the nature of public policy work, it is harder to sustain programmes that are about a better future than those that are about dealing with a crisis.

The public sector will not, and should not, aspire to be 'like the private sector'. However, there are aspects of the private sector that are useful to enable the 'Civil Service to be the best possible Civil Service'. The capability reviews, professionalism agendas and other initiatives in place recognise the need for change. Our research suggests that the pace of change still needs to be increased dramatically. This does not have to be through implementing new technology. Frequently the challenges are more cultural, giving people autonomy and sign-off authority, reducing the complexity of forms, and taking people off copy lists. The quality of relevant data needs to be improved and delivery models clarified to relate that data into a policy framework focused on outcomes. Moving people from being busy to being productive is something the private sector has worked on for years, and few organisations would claim to be perfect yet. They have found that reducing and shortening the number of internal meetings, and inviting fewer people is helpful. In extreme cases individual senior executives have been known to take all the chairs and tables out of meeting rooms as keeping people standing does have a dramatic effect on the length of meetings! Asking staff for suggestions on how processes could be simplified is another useful tool for private-sector companies. Acting on suggestions reinforces management commitment to the programme and gives it credibility. Streamlining and 'lean' programmes are widespread in the MOD, HMRC, the NHS, the DWP and the justice system. As HMRC found most dramatically, the challenge is mainly cultural rather than designing processes and services.

Some processes seem to be adhered to without appreciation of their context and implications, 'the Civil Service is not sure if it is about administering things or improving things'. There is almost 'wilful under-resourcing – a slavish application of cost savings and resourcing without any organisational sense of priorities'. The interviewees recognised there is widespread recognition of the requirement for cost savings but the culture, incentives and motivations of individuals militate against them; 'there are too many people who are underemployed. This might be because of an inability to move people to pressure points quickly'. Defra has implemented 'Flexible Staff Resourcing', a process to move people quickly to prioritised projects. A number of other departments are looking at this process.

Performance, in the widest sense of the word, came up in every single interview. Sometimes this referred to the organisation itself inhibiting performance, 'senior people do a lot of fire-fighting around the issues of the day'. 'There are three agendas – political, day-to-day operations and change programmes. In the private sector the roles of Chairman, CEO and COO are clearly separated. Senior people in the SCS are often seriously overloaded so they can only skate across the top'. The impact of the political machine is felt particularly strongly at the moment, the 'political will changes, you get blown around by the wind more'.

'Ministers are not connected to the delivery agenda of the Department', which is not helped by the tendency of civil servants to blame ministers, 'we know this is mad but the Minister has said so' – 'no doubt there is a grain of truth but it is a far overused excuse'. The interviewees were acutely aware of the political context within which they worked, and accepted it. But nonetheless they would like to see some priorities that stick, old work stop as new work comes in, and senior people freed to concentrate on them rather than minutiae.

Academic research has shown that new arrivals into organisations typically adapt to the existing culture within weeks and our interviews illustrated this inertia – 'people come in with the skills required but often find the culture prevents them from really using their skills, the organisation gets in the way. It is not a learning organisation'. There is a sense that you could come in and do a good job but then leave and there would be no lasting changes, 'I am getting experiences I wouldn't get any other way. But who ultimately will benefit? I could do my four years and then be off and I will have had a lot of the benefit but not helped the longer term agenda'.

Performance is hugely affected by rapid movement of staff from one permanent job to another. This was an issue mentioned by almost all of our interviewees. 'Some people are supposed to do 2.5 years and others 18 months, it really isn't much. There is a lack of expertise and cultural memory'. 'Rapid turnover of staff also means few specialists, which affects overall performance'. 'People are generalists and then asked to do things they don't understand. Talking about things isn't the same as doing them'. Another said, 'I would like to stay in the SCS but I really want a job for four-to-six years to see something through and the SCS doesn't work like that'. In the private sector we have seen people gradually stay in their jobs for longer. It used to be the norm that people would move on every couple of years ('a year to learn the job and a year to do it well' was often the mantra). But now we are seeing people in the private sector staying in their jobs much longer, typically four-to-five years for middle management, although CEO tenures are falling.

Rapid movement from one job to another inside the Civil Service does not provide the same experience that people get when they move to different organisations, or have a spell working abroad. People who have made the move from central government to the wider public sector, for example to work with a local authority, said, 'if only I knew then what I know today, I would have designed policy very differently'. There are some, but few, existing programmes, such as placements for fast streamers out in the wider public sector, which provide formalised support for civil servants to experience working in other scenarios, private sector or abroad.

The SCS does not have a reputation for being a learning organisation. The announcement of a new CEO for the National School of Government (NSG) is an ideal opportunity to take a fresh look at its mandate and programmes to change this. Organisations such as the Whitehall & Industry Group or the NSG could take a key role in enabling understanding and sharing best practice, mixing with people from other departments, and giving people from the private sector a place where they can have a voice. The emergence of the Institute for Government is another opportunity to define a new agenda addressing performance and leadership.

|

Recommendations Our research suggests that departments should analyse end-to-end processes, paying special attention where processes touch those in other parts of the organisation or other organisations, to look for process or approval steps which could be removed. This is not new and departments have been aware of this requirement for a long time, but the focus needs to be on the internal workings of a department in order to get the full benefits of improvements they are making to their front-line delivery processes. Our analysis also suggests that it could be valuable to run a number of pilots of 'Flexible Staff Resourcing'. Additionally, progression to senior roles should include more emphasis on 'get out to get up' – taking roles in the private sector, working abroad, or in the wider public sector. In the SCS it is the norm for Permanent Secretaries to stay in their jobs for four years and it would be effective for that practice to be devolved to the lower levels of the SCS. Learning organisations recognise the value of development through plans set as part of the appraisal process, with actions taken seriously and reviewed on a regular basis. We recommend that the SCS put more focus on this aspect of their appraisal process. |

Finding 3: Managing day-to-day performance continues to be a challenge

Managing poor performers is at the heart of the performance issue and every interviewee mentioned it. Almost all the interviewees believed that their department did not differentiate between good versus poor performers by developing the former and encouraging the exit of the latter.

The interviewees acknowledged that the worst of the performance issues are below SCS level. They also recognised that the performance management processes, agreed with the unions, were very hard to carry out, especially managing people out. But, 'it's still like a gentlemen's club', and newcomers who follow instructions to reorganise find that 'other colleagues do very little and the same dead wood is still floating around the organisation, festering elsewhere'. The situation was most damningly summed up by one of the most senior interviewees, 'the public sector is a social service in one sense, it does employ people who are not employable anywhere else. If it is going to do that, it should be explicit and do it properly'. 'I spent three hours at the Cabinet Office discussing making one person redundant who had been supported by colleagues purely as a social service – and no-one else seemed to find that bizarre'. Another pointed out that the downside of a flexible and tolerant culture is that performance is not well managed. 'Objectives are not set in a clear way, then monitored, then action taken. Poor performance is just tolerated'. Another, on secondment, said, 'there is a population of also-rans at the worst end I wouldn't keep and if I were staying that's one of the things that would put me off'.

The role of the unions is critical in managing poor performers and pay settlements. Some unions have expressed concerns over the changes that cost-cutting pressures, moves to a globally managed economy, and increased participation of the private sector in delivering public-sector services will mean for their members. However, to protect as many public-sector jobs in the United Kingdom as possible, it will be in union members' interests to ensure they are highly skilled, productive and have a track record of delivery. This will mean a number of changes such as increasing the focus on skill development but also modernising and streamlining the performance-management processes.

A theme emerging from our interviews was that generally, the best of the best are promoted to the SCS. But there are performance issues in the SCS too, as there are in most large and complex private-sector organisations. People do get promoted beyond their ability, or out of their area of technical competence into line management. People's attitudes and motivations for work do change during their careers. This is true for both private and public sectors. However a general assumption is that in the private sector, partly because there are few final salary pensions any more, a wider variety of options and deals exist.

Most of the interviewees also mentioned appraisals. 'The Government has a peculiar appraisal system and a committee system of awarding tiny bonuses – which takes a huge amount of time'. 'If you write anything that isn't absolutely glowing in appraisals they start appealing it – they just won't accept it. They fight over every word rather than accepting feedback'. As noted above, the development aspect of appraisals gets little attention, 'you have to go back constantly and ask them about development areas'. Where our interviewees were on fixed-term contracts or secondments some of them found it hard to get teams or get things done. 'It is very gradist; whose authority you are coming with will influence how people will react'. They remarked that, 'it is a problem to get people to do work. I am not part of their future so my leverage to get things done is low'. Another said, 'I kept being sent absentee reports and didn't understand the implications at first. Then I read a newspaper report comparing private- and public-sector absence levels and realised that it's a real issue. But it's like an attendance register – no-one is sending information about performance or delivery – it just says if they physically turn up'. There is a huge focus on managing the process rather than the outcome. 'I spent a day at a worthless Cabinet Office meeting debating performance-management process details when my problem is getting people even to set objectives for their staff. Some simply refuse saying they'd rather set objectives at the end of the year when they know what's been achieved'.

The appraisal system was summed up, for us, in the comment, 'there are two kinds of love parents give their kids – loving and protective, and that which says, have a try but I will be there if you need me. The Government gives a lot of the first and none of the second. Its children therefore lack confidence'.

Most interviewees mentioned money – their own pay and that of others, 'pay is a problem, working with professional people who are more or less on the minimum wage is a real shocker'. A cultural shock was finding that, 'I have absolutely no control to adjust relative levels of remuneration for my team'. One interviewee pointed out that, 'there have been lots of cuts and there are lots of interims and shadow staff. If you could just pay the civil servants a little bit more you would keep them – it would make a big difference – and avoid the potential issues of security and lost knowledge'. Those interviewees who had gone into the SCS as permanent members of staff, or on fixed-term contracts, said, 'if anything drives me out it will be the money'. At the same time they are aware they are likely to be at the top end of the salary scales, which creates tensions between them and their long-term public-sector peers.

It is recognised and understood that any pay settlements in the SCS have a knock-on effect on other parts of the public sector. When ministers set the pay envelope for the SCS they are very conscious of the wider context, which means it is likely that pay will continue to be constrained. We also believe that few senior civil servants really realise what their pensions are worth to them. In financial terms, the pension does go a significant way to bridging the gap between private and public, especially in middlemanagement levels, for people with many years of service.

There was discussion about the psychological contract in the SCS. There was some feeling that there is an implicit acceptance in the Civil Service of low performance expectations in return for poor pay. This lies behind inadequate performance management, high absenteeism and cynicism about change. The practice of 'shunting', moving a poor performer on to another job in another department, appears to be a more common method of dealing with poor performance than moving individuals out of the service altogether. The overall voluntary attrition rate of 3 per cent is lower than private-sector organisations would think healthy and is perhaps linked to the pensions discussion. Rapid turnover of staff within the Service, with people moving internally from job to job quickly, replaces the more common private-sector practice of people moving to a different company.

The emergence in the media of apparently-substantial bonuses and exit payoffs to senior civil servants has attracted some media commentary.2 Are civil servants being rewarded for failure? Is the public sector importing private-sector practices without improving performance?

Bonuses are long-established in the private sector and reflect a mindset of 'paying for performance' but also protecting the company against downside – if earnings turn down, then bonuses can be trimmed back more easily than other elements of compensation. When it comes to motivation, there is much greater scepticism – unless bonuses are very substantial, all the evidence suggests that pay exerts only a short-term impact on motivation. Job challenge and career development are usually much more significant long-term motivators. Even where bonuses are very substantial in the City, many HR directors will admit that they are frequently 'wasting the bulk of the money' on paying bonuses for the performance they would be getting in any case – but the 'signalling effect' in a competitive talent market would result in disastrous turnover if they cut bonuses. Approximately 90 per cent of eligible private-sector employees receive bonuses compared with 65 per cent of eligible senior civil servants.

The Civil Service is subject to political limitations on pay and, although there are constraints in the system, the current 2 per cent limit fails to reflect the intense competition for senior talent and leaves permanent secretaries earning only between £140,000 and £270,000. Bonuses in the Civil Service are limited to 8 per cent of the payroll with an average payout of £7000, yet have proved controversial – externally because bonuses have been paid to senior civil servants in departments that have had 'headline failures', and internally because they are alleged to undermine team performance. Performance-related pay is more challenging in the public sector with issues of measurement, lack of single-point accountability and the possibility of eroding intrinsic motivation.

Exit payoffs are equally controversial in the private and public sectors. It is understood that private-sector organisations recruit to fuel growth and downsize to accommodate reductions in their markets. Additionally they are likely to have a mixed workforce including permanent staff and fixed-term contractors to give them further flexibility. Private-sector organisations are likely also to have early retirement programmes, extended sabbaticals or flexible working to help manage resource costs. They will also, as necessary, pay off senior (and sometimes more junior) people, either if their particular role is no longer required, or if they are not performing well. Exits will be backed by a business case including quantified economics and a strategic view of the talent pool and capabilities. Most senior exits will be 'compromise agreements' rather than contractual or company-wide schemes.

Payouts to senior civil servants may grab the headlines3 but the Civil Service needs to be more like the private sector in this respect. It needs to differentiate more, not less, on performance. The business case for exit payments is not only the cost saving, it is also about the signal of removing unproductive people and layers of old behaviour. The business cases for exit payments in the Civil Service are, of necessity, extremely robust. The SCS pension arrangements are so generous that they outweigh higher private-sector salaries. Exit payments calculated to include pension accommodations will be high. In real terms however they represent savings compared with keeping poor performing people.

|

Recommendations Managers should be provided with as much case management support as possible to help them with their poor performers. Also, managers with experience of the process should be grouped together as specialists to buddy managers experiencing it for the first time. In addition, over time, the SCS could move towards a process of giving high-performing people salary increases and the poor performers no increases. Further, the appraisal process should be managed with rigour and discipline, from the top and down through every level. Every member of the SCS should have clear and measurable objectives and a development plan they take seriously and review regularly. These processes do exist; they may not be perfect but few are. It's the implementation that is key. Leadership is critical here, the most senior people have to take the process seriously and demonstrate through their actions that they are doing so. Their actions will be mimicked throughout their organisations. Pay bands and performance-pay should be restructured to attract and retain the best, and to depart from the discredited 'poor pay for indifferent performance' model. The Civil Service should strengthen its resolve, particularly with respect to senior people who are deemed to be poor performers. Hard questions should be asked as to how cost-effective it is to keep underperformers on salary and contributing to their pension schemes. |

Finding 4: The SCS has imported skills but challenges remain

There is an ongoing debate about whether the SCS 'is a policy organisation that gets other organisations to deliver, or a delivery organisation'. The Civil Service is a very complex organisation made up of many widely differing departments, agencies and NDPBs, with various constitutional powers, structures and priorities. One size does not fit all and, although there are always risks in generalising, the interviews indicated strong trends across many organisations. There are many real delivery challenges in the SCS and there is a lack of delivery capability. This would be helped if 'they understood the private sector more, especially roles like FD, Commercial Director, and so on'. Some senior civil servants 'have never had an operational business to run, and you would never get that far in the private sector without operational experience'. A number of interviewees were in programme management roles, and came from environments where the emphasis on building a track record of delivery was the driver for promotion.

The SCS has a number of initiatives in place to put more focus on delivery. Bringing in people from the outside, partly to augment capability and transfer skills, is one of those drivers. The creation of the current, much shorter list of public service agreements (PSA), many of which are cross-departmental, is another. Our sense is that the people at the top of departments do their best to shield lower grades from the winds of political change and day-to-day firefighting to which they themselves are subject.

However, there are still gaps in programme management, delivery focus, and closure – knowing the start and driving to an end. But also there are gaps in everyday operational delivery – finance, people and targets. 'There is a gap between ideas and execution'. They are 'very good at outlining policies and identifying what needs to be done, but really bad at getting that to connect with people who have to understand it and buy into it for change to happen'. The SCS is also not good at ending certain activities to make way for new ones, 'we need to stop doing some things and deliver some stuff'.

Interestingly, the interviewees didn't talk about lack of financial or IT professionalism, which may be a positive reflection of the emphasis on building those skills in the last few years. Many of them did, however, talk about the lack of commercial skills, 'the biggest most obvious gap is the commercial understanding. It is confused with an ability to procure and it doesn't mean that'. 'I don't see very often an ability to see across the portfolio'. 'Projects could be conceived and delivered so much better if there were a real understanding of commercial issues'.

Deciding when and how to use external consultants is also patchy. Some departments have strong capabilities and experience in deciding to bring in external consultants to help deliver specific projects for them. They appreciate the difference between consultants and interim staff and have robust business-case creation and risk-management processes. In other places these capabilities still needed development. There can be 'an inappropriate use of consultants. You still see evidence of a long time ago when you got a consultant in because it would be someone else's decision and someone else's fault'. 'We need intelligent buying around non-core capability especially when you only need things once'.

Many people move roles quickly, and because of this, it is hard to build and retain cultural history. But the political context contributes to this too, as new people in charge bring a desire to do new things. 'They don't value the application of previously agreed solutions – if you meet a new Minister who says "what can we do here?" and you say, "properly implement the previous incumbent's policies", it isn't likely to go down well'. It is hard, therefore, to stick to a strategy, keep the same priorities, and hold individuals accountable for delivering results.

Developing policy is clearly a huge capability. However, one Permanent Secretary commented that, 'we still make policy in the same way as we did 20 years ago – but surely cross-governmental working demands new approaches'. A Director-General in another department observed that, 'technology has actually been used to degenerate our policy-making process – everyone is copied on emails and papers are lower quality with lowest-commondenominator thinking'. And 'the caste system is about policy and for my money policy without execution is just table talk'.

Agility in creating and delivering public policy has been on the Government's agenda for over 20 years. Beginning with the 'next steps' agencies, there has been a series of initiatives focused on greater flexibility and improved performance. The earlier initiatives relied on new structures – agencies and project teams welded into the structure. Later, specific projects or programmes were created and ring-fenced with budgets, staff and often premises, to enable them to concentrate on delivering their projects. Both approaches – creating new organisations and setting up autonomous programmes – engender resistance to change and tend to accumulate resource and cost. The early 2000s saw, in both private and public sectors, extensive use of collaborative themes or services working across organisation boundaries and throughout supply chains, to give coherence to otherwise unstructured sets of activities. Following the Enron case, again in both private and public sectors, there has been a massive focus on process, accountability, and being able to audit decisions.

There is now, at last, a move towards agility and flexibility. People are being moved quickly to where they want to be; where their talents are needed by the organisation. Large and complex organisations, programmes, processes, supply chains and customer bases are a fact of life and everyone in both the private and public sectors, must elevate nimble movement of staff and leaders to a priority. The current situation in the SCS is that people move quickly from their permanent jobs, rather than changing projects or roles. There is a significant difference between focusing on managing a career and looking for the next promotion, and simply taking on the next project from the pool. Flexible Staff Resourcing introduces a project-based resourcing methodology, with people moved temporarily to projects requiring their skills and experience. While some may stay with a project for a considerable length of time, others may move projects quickly. Fundamentally, however, they would remain in the same underlying job, reporting line and cost centre, building speciality expertise. Figure 1, above, illustrates this progression.

A new aspect in the evolution of the SCS is the introduction of cross-governmental PSAs to institutionalise integrated government – major policy priorities require a range of departments to work together to deliver the outcome: achieving obesity goals requires the Departments of Health, Children Schools and Families, Culture Media and Sport and others to work together. Achieving climate change targets for 2020 requires Defra, BERR, Department for Transport, DCLG and many others to work together to deliver a portfolio of up to a hundred projects.

Historically, the task of leading cross-governmental work has fallen to the Cabinet Office. Behind the scenes, special advisers have brokered compromises and exercised persuasion to align departments. However, for the new suite of cross-governmental PSAs, a governance regime has been devised, consisting of single-point senior responsible owners (SRO) with cross-departmental boards to drive delivery. Private-sector experience indicates that to get organisations to work together across boundaries there has to be trust, a firm mandate and shared vision in addition to a single point of ownership. These attributes are still being built in the SCS. Although many civil servants commented that joint working is better than it ever has been, some of our interviewees spoke about examples of concealing data and analyses, taking decisions without consultation, and so on. They added 'it is not uncommon for papers with faulty logic to be circulated directly to ministers and special advisers instead of via the knowledgeable departments'.

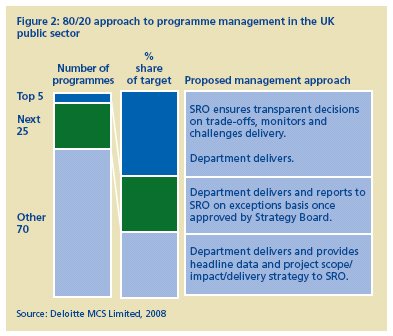

The hierarchical structure of departments, the fact that Accounting Officers are ultimately responsible for their departments, and the vast workload and fast changing priorities of the SCS, all combine to focus management within departments. In spite of the crossdepartmental PSAs the main focus on delivery is still through individual departments. Even on the largest cross-governmental PSAs, typically only a few programmes will need to be actively managed across departments; the vast majority will be departmentally led, with central reporting the exception.

The challenge for ministers and officials at the centre of government is to make cross-Whitehall working effective – focusing on the few critical priorities rather than the undifferentiated mass of departmental initiatives, ensuring that trade-offs between conflicting policies are made transparent, and providing independent programme management support. Typically, cross-governmental PSAs generate a myriad of initiatives, of which a handful are disproportionately important to delivery of the target, and require cross-departmental action and programme management by the SRO. This 80/20 approach to programme management is the norm in the corporate world.

Trade-offs are inherent to all the cross-governmental PSAs. They usually include trade-offs between policy goals, such as limiting climate change and providing secure affordable energy, or between policy goals per se and the competitiveness of the UK economy. By their nature, the cross-governmental PSAs deliver largely through private-sector activity outside government control but within government influence. Transparency, a holistic view of the problem, clear priorities and effective programme management encompassing all the SROs' offices are essential if these complex programmes are to deliver. 'It's shocking how ignorant many departments are of their delivery chains and how to influence the long-term investment climate. We prefer repetitive policy reviews that create policy blight and initiative-itis'.

So far this is a wholly internal discussion – Whitehall talking to Whitehall. By definition, cross-governmental PSAs entail more complex delivery chains, engaging more public servants from different agencies and local and regional government, and frequently requiring investment by industry and the alignment of citizen behaviour. Influencing the performance of complex delivery chains often requires new processes and behaviour rather than new structures or expensive new systems.

|

Recommendations There are initiatives in place to identify and broadcast best practice and our research suggests they should be encouraged through different forums and including wider groups of people. Additionally we would suggest that teams with experience and specialist skills be used as 'swat teams' in several different programmes, instead of breaking up a team at the end of a project and individual members moving to new jobs. For example teams with a track record of creating business cases, managing procurements, assessing benefits realisation and carrying out post investment reviews could work together for several years on successive projects in other departments, training and coaching people as they go along. Our survey suggests that more use of the 'Flexible Staff Resourcing' model that Defra has implemented could be beneficial across the wider public sector. This model allows staff to be deployed quickly to projects, keeping up momentum, enabling senior teams to maintain focus on top priority projects, and aligning people with the most appropriate skills to resource requirements. Further, from the fast stream up, a different model of career development should be adopted, which intersperses operational, delivery and policy roles through careers. Private-sector (and international) experience is valued and should be encouraged, especially for top talent. The private sector can play an important role here, particularly with the rise and recognition of a 'Public Sector Industry' – the private sector's contribution to delivery of public services. Finally, the following actions should be taken to improve delivery of cross-governmental PSAs:

|

Conclusion

Despite the challenges highlighted in this report, the SCS remains a highly capable, creative group of people, whose underlying desire to improve public services and make government more effective makes a real difference. The intellectual capacity among senior figures of the UK Civil Service is formidable, and across traditional functions such as top-down policy-making, supporting ministers, and preserving the continuity of government, they remain world leaders.

Yet a convergence of external pressures is driving the need for change among Senior Civil Servants. The perspectives of the external appointees set out in this report show that although the SCS is tremendously admired for the things it does best, there are measures departments could take to improve or simplify key processes, place renewed emphasis on delivery outcomes, and thoroughly review the individual and organisational performance management regimes that have such an impact on business culture and effectiveness.

In confronting these issues, the leadership of the Civil Service should not retreat from the pay issue, which is central to improving performance and transferring institutional emphasis from process to delivery excellence. Leaders must also consider their response to a changing delivery environment, which places new demands on departments' commercial functions and their management of delivery agents and suppliers. Improving skills and capabilities in these areas is at the heart of the solution to these challenges.

To drive these changes will require engagement from SCS leaders and intervention to strip away Whitehall boundaries. The development of innovative approaches to working will drive principles of flexibility and collaboration across the delivery chain. Unpicking deeply embedded behaviour and processes, and age-old responsibilities will be difficult, but the rewards for success are likely to be considerable.

Footnotes

1. The delivery challenge for the next government, Deloitte & Touche LLP, May 2007.

2. For example, see: Bonus payouts for HMRC staff that lost benefit discs, Accountancy Age, 10 January 2008.

3. For example, see: £82m NHS payoffs, Daily Mirror, 25 August 2007.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.