The UK company provides many tax advantages to international groups as a holding company, but the potential liability of a UK company to deduct basic rate income tax from annual interest it pays to overseas lenders should not be overlooked.

For many international groups this potential withholding tax liability is overridden by the interest article of a UK double tax treaty, if the UK company's lender is resident in a Contracting State. However, this note assumes there is no possibility of treaty or EU Directive reliefs. The most common reason for this is that the lending company is an offshore company, i.e. not registered and resident in an EU Member State and not party to a suitable tax treaty with the UK.

Examples of offshore companies lacking a tax treaty with the UK include the British Virgin Islands and the Cayman Islands. Examples of offshore jurisdictions with tax treaties with the UK but whose provisions are unlikely to override UK taxing rights include Jersey, Guernsey, and the Isle of Man.

In the above scenario, HMRC's policy has almost always been to regard the interest income paid by the UK company as liable to a deduction (made by the payer of the interest) of basic rate income tax. The rate of tax is therefore 20% of the gross interest paid. HMRC reason that the income must be regarded as having a UK source, on account of the debtor being UK resident. If this reasoning is not challenged (and unfortunately some advisors often accept HMRC's interpretation of the law as correct) the offshore lender will be liable to the basic rate income tax charge on its gross interest, as s368(2) Income Tax (Trading and Other Income) Act (ITTOIA) 2005 states:

" Income arising to a non-UK resident is chargeable to tax under this Part only if it is from a source in the UK."

HMRC say in their Savings and Investment Manual (SAIM 9000):

"...whether or not tax should be deducted from interest paid on an overseas loan depends on the source of the interest. If the interest has a UK source, tax must be deducted. If it does not, then tax should not be deducted."

This is clearly correct. HMRC then go on to say:

"Whether or not interest has a UK source depends on all the facts and on exactly how the transactions are carried out. HMRC consider the most important factor in deciding whether or not interest has a UK source to be the residence of the debtor and the location of the debtor's assets."

The first sentence of the paragraph immediately above is consistent with authority on the source of interest, but the second sentence is not.

The "Greek Bank" case

Until the case of Ardmore, the common law authority for the source of interest was the so-called Greek Bank case (Westminster Bank Executor and Trustee Co v National Bank of Greece (1970) 46 TC 472). A bank in Greece had issued bearer bonds denominated in sterling. The bank defaulted on the loan, and the Greek guarantor paid the interest. HMRC argued that the interest had a UK source because although the original guarantor had no branch in the UK, the successor guarantor resulting from a corporate amalgamation, acquired a UK branch so that the bonds were enforceable in the UK. The House of Lords held that the interest had a non-UK source based on various factors including the non-UK residence of the debtor and the guarantor, and the fact that the loan was secured on lands and public revenues in Greece. Payment of interest was to be made in sterling, either by remittance from Greece to the paying agents specified in the bond or, at the option of the holder, by cheque issued in Greece but drawn on London payable out of funds remitted from abroad. Lord Hailsham also made an opaque reference to the bond being "a foreign document".

Pursuant to the Greek bank case, HMRC has adopted a multi-factorial approach to determine the source of interest, with greatest weight being attributed to the residence of the debtor.

Until the Court of Appeal judgement in Ardmore, it had not been clear what respective weight should be given to the various possible factors that fell to be considered in the Greek Bank case. Following Ardmore, the issue of weighting is clearer, although as underlined by the Court of Appeal, each case is "acutely fact sensitive".

Ardmore Construction Ltd

Ardmore Construction Limited was and is a UK resident company owned and managed by two brothers, also UK resident. The activities of the company were essentially confined to the UK, where a trade was carried on. Using its working capital, Ardmore subscribed for shares in two British Virgin Islands companies owned by two Gibraltar trusts settled by the two brothers respectively. The sums subscribed by Ardmore in the two BVI companies were then loaned by the BVI companies to the two offshore trusts. The trusts then lent the sums received to Ardmore. The loans were not secured on the UK assets of Ardmore, and the loan documents were governed by the laws of Gibraltar. The borrower (Ardmore) and the lenders (the Gibraltar trusts) submitted to the exclusive jurisdiction of the Gibraltar courts. Interest was paid from Ardmore's bank account in the UK to the lenders' bank accounts in Gibraltar.

Counsel for Ardmore argued that the source of interest was to be found by ascertaining the "nationality" or "residence" of the loan document (echoing Lord Hailsham's reference to the bond in Greek Bank being a foreign document). This was an argument against a multi-factorial approach, which ultimately failed before the Court of Appeal. In the alternative Ardmore argued that if a multi-factorial test was the proper test, the FTT had erred in affording too much weight to the residence of the debtor (the FTT judgement concluded that the factors of residence and the source of funds outweighed that of jurisdiction and actual payment). The third ground of Ardmore's appeal was that the place where credit is provided is the source of interest.

The Court of Appeal rejected Ardmore's arguments, and fully endorsed the reasoning of the Upper Tribunal (UT). This was to the effect that a multi-factorial approach is required to determine the source of interest for income tax purposes. This torpedoed the "place of credit" test advanced by the tax payer.

The UT considered the factors identified in the Greek Bank case as relevant to the determination of the source of interest.

1. The residence of the debtor

2. The residence of the original guarantor (if any)

3. The location of the security originally provided

4. The ultimate or substantive discharge of the debtors obligation.

The UT also considered factors of little or no weight, i.e. factors not mentioned in Lord Hailsham's judgement in the Greek Bank case, or which were known facts but did not outweigh the factors referred to in 1-4 above:

a) The residence of the creditor or the place of activity of the creditor

b) The place where credit was advanced. The original borrowing in the Greek Bank case was raised in London but that did not weigh in favour of the UK as a source of the interest

c) The place of payment of the interest. Under the original bonds in the Greek Bank case, the place of payment was London (either by presentation to a London bank or, if presented to the original borrower in Greece, by cheque on London). This factor was rejected by the House of Lords in favour of the ultimate source of the principal debtor's obligation, which would have involved a remittance from Greece

d) The jurisdiction in which proceedings might be brought to enforce the interest obligation. In the Greek Bank case, the English courts would have had jurisdiction, but this did not prevent the interest having a non-UK source

e) The proper law of the contract. In the Greek Bank case, the proper law of the contract was English law

Court of Appeal judgement in Ardmore (HMRC 2018) (EWCA Civ 1438)

The leading judgement was given by Arden LJ. Her conclusion was that the test of source is a factual exercise, and that in each case it must be asked whether a practical man would regard the source as in the UK or not. Arden LJ noted that Lord Hailsham applied a matter of fact approach in Greek Bank, and avoided applying any legal concepts or rules. The Lady Justice said that one must look to the "underlying commercial reality", or the substance of the matter:

"There has been much reference to a multi-factorial test. To that I would add that the correct approach is the practical approach and that it is not merely multi-factorial but also acutely fact-sensitive. The court or tribunal must examine all the available facts both singly and cumulatively".

In short, the practical man would see that all the substantive matters pertaining to the loan arrangements were in the UK in the Ardmore case. The debtor, its assets, and the source of funds used to pay interest were all in the UK. The Gibraltar factors in the loan arrangements i.e. that the loan agreement was subject to Gibraltar law and that the Gibraltar courts were given exclusive jurisdiction, were insubstantive factors, that would remain latent so long as there was no dispute between borrower and lender.

The ratio in Ardmore seems to be that in any given case where the source of interest needs to be determined by a UK court, the enquiry is a factual one which takes into account the commercial substance of the loan arrangements. To the extent that the arrangements will consist of a collection of facts, the test is multifactorial, but this should not lead to the conclusion that there is a standard checklist to be applied. Instead, all factors should be considered, but depending on the circumstances, some factors will carry little or no weight, and other factors will carry more weight if they go to the heart of the commercial realities of the loan arrangements.

UK companies are frequently established to act as holding companies in international groups. The advantages the UK company provides as a holding company relate to the UK's significant double tax treaty network and UK corporation tax exemptions for foreign dividends, and capital gains arising from the disposal of substantial shareholdings. The absence of any form of withholding tax in the UK on dividends paid to non resident companies or individuals is also a significant advantage.

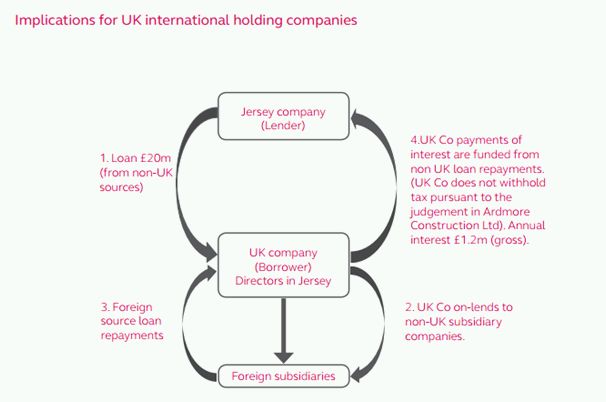

In the example above, the UK company is being used to finance group subsidiaries in Europe. Loans are provided from an offshore holding company based in Jersey to the UK company to enable the UK company to make loans on commercial terms to group subsidiary companies. The directors of the UK company are also resident in Jersey, and the UK company makes repayments of interest and principal from its non-UK assets, i.e. from debts due from its non-UK resident subsidiaries.

It is arguable that the UK company in this example could regard its interest payments to its Jersey parent company as having a non-UK source. This would be on account of several factors including that:

1. The UK company would appear to have a substantive residence in Jersey for the purposes of jurisdiction, if it has an active place of management and place of business there. Admittedly the UK company has a UK registered office, and therefore a dual residence in Jersey and the UK, but the UK residence is a more artificial residence based on incorporation. The UK residence is at best a neutral factor, or alternatively the residence in Jersey displaces the UK residence on substance grounds. It is important to make the point that "residence" in the context of the source of interest does not refer to tax residence, but to the place where the company carries on business.

2. The source of the monies from which the UK company satisfies its debt interest obligations derive from foreign i.e. non UK resident debtors, and the UK company's business of lending to overseas companies is conducted and administered in Jersey. If non-UK assets are charged as security for the parent company loans, this would create another significant foreign source factor (although tax advice should be taken in the country where the security assets are located to ensure this does not create local tax or other legal problems).

Conclusion

The case of Ardmore Construction Ltd makes it clearer that whilst the residence of the debtor is likely to be a factor of weight in any enquiry to determine the source of interest payments made by UK companies, it is not, as HMRC have previously assumed, the prime factor or determinative factor. The case of Ardmore indicates that UK registered companies can participate in international group financing transactions without necessarily exposing offshore corporate lenders to UK income tax liabilities on interest paid by UK subsidiary companies. However, as the Ardmore case makes clear, the outcome of an analysis of any particular case is acutely fact sensitive.

Different tax considerations apply where a UK company pays interest to an overseas lender whose country of residence has contracted a double tax treaty with the UK.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.