Foreward

In this Review, Roger Bootle, Economic Adviser to Deloitte, turns his attention away from the gloom of our immediate economic prospects to consider what the postrecovery economy might look like.

Once this recession is finally a memory, if not a distant one, the landscape will have changed dramatically. Roger believes that, in sharp contrast to the performance of the last ten years, neither the consumer nor government sector will play much of a role in driving economic growth over the next decade. In contrast, the star of the show will be the exporting sector, boosted by the drop in the pound.

He dismisses fears that the manufacturing sector has shrunk too far, instead arguing that the UK's manufacturing base can undergo a mini revival – helping to fill the hole left by the financial services sector's shrinking share of the economy.

UK exporters can clearly play to their traditional strengths such as aerospace and pharmaceuticals. The lower exchange rate will also boost services exports, from tourism to consultancy services.

Roger thinks that the implications of these sectoral changes will be wide-ranging. The renewed emphasis on manufacturing could raise trend productivity in the economy, as well as boosting the Northern regions of the UK. But there is no reason why London's share of the economy must shrink. Its reliance on financial services is smaller than is commonly thought and London will benefit from becoming a cheap place for international firms to locate.

Once again, I hope that this Review helps you in both your immediate and strategic thinking.

John Connolly

Senior Partner & Chief Executive

Executive Summary

- A recovery could be months away or it could be years away. Sooner or later, though, recover the UK economy will. And when it does, the landscape will have changed beyond recognition.

- After a decade during which consumer spending growth outpaced overall GDP growth, we expect now to see a decade where consumer spending underperforms.

- Meanwhile the government will have to cut, or at least freeze, its spending in real terms for several years in order to reduce its sky-high borrowing levels.

- The star of the show will be the external sector. Although concerns have been voiced about whether the UK's manufacturing sector has shrunk too much, we see no reason why it cannot experience a mini-revival. Meanwhile, it is not just manufactured goods which will benefit from the drop in the pound – so will exports of services, from tourism to consultancy services.

- We think that, over the next decade, manufacturing's share of the economy could temporarily grow from 11% to 13% or even 15%. In contrast, the financial sector's share could shrink from 8% to more like 5%.

- The drop in the pound should help the UK to play to its traditional exporting strengths – such as the production of pharmaceuticals and aircraft. But with imports becoming less competitive, the lower level of sterling could have a wider impact, as more of the goods that the UK needs are produced domestically.

- Meanwhile, the services sector is particularly fertile ground for new or nascent services to spring up and expand, such as the provision of "green" consultancy services. And both the online and supermarket sectors could yet broaden their reach even further.

- The implications of these sectoral changes will be wide-ranging. For example, the renewed emphasis on manufacturing could boost trend productivity in the economy, given that manufacturing lends itself more easily to technical progress than the services sector. This could offset any dent to trend GDP growth caused by lower net migration.

- However, the regional implications might be smaller than is commonly thought. Regional disparities have shrunk considerably as manufacturing-dependent regions have diversified their economies. Meanwhile, London's reliance on the financial sector tends to be overstated – wholesale financial services account for at most 10% of its economy.

- But there remains a difficult period to get through before we see this "new world". The economy now looks likely to contract by some 4% or so this year.

- The outlook for next year depends heavily on the success of the various policy measures. However, mounting bank losses suggest that bank lending is unlikely to rise strongly. And the likely effects of quantitative easing are highly uncertain. For now, then, we retain our view that the economy will contract again in 2010 by around 1% and still think there is a big risk of a period of persistent deflation.

Roger Bootle

Economic Adviser to Deloitte

After the storm

What the UK will look like after the recovery

No-one knows exactly when the UK economy will pull out of this recession. While the optimists are looking for a recovery later this year, the downturn could easily continue beyond even next year.

Sooner or later, though, recover the UK economy will. But when it does, what will it look like? Will the economy grow in the same way as after the last recession? Or has the downturn changed the landscape for good? In this Quarterly Review, we consider what the post-recovery economy will look like. Who will be the winners in this new world? And who will be the losers? And what knock-on effects will the changes have?

Back to normal?

The best place to start is with a brief reminder of how the economy looked in the years running up to the recession. Bank of England Govenor Mervyn King summed it up well when he nicknamed it the "Nice" (non-inflationary constant expansion) decade. Annual real GDP growth over the ten years to 2007 averaged 2.9% – above its long-run average of 2.5%. In no year did GDP growth ever slip below 2%. Meanwhile, never once did inflation stray more than 1% away from its target.

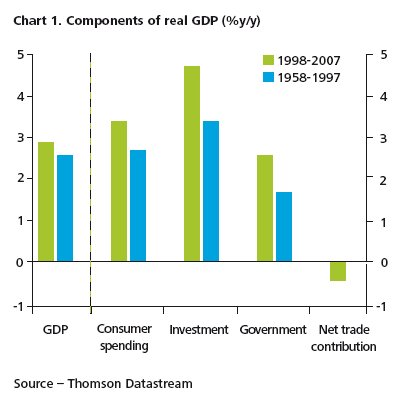

However, as is now costing us dear, that growth was seriously unbalanced. (See Chart 1.) Consumer spending grew at an average annual pace of 3.4%, compared to its average rate over the previous 40 years of 2.7%. Government spending and investment also grew robustly by previous standards. In contrast, net trade made a positive contribution to GDP growth in only two years, as the current account deficit went from a position of balance to a deficit of some 3% of GDP.

These imbalances both reflected and exacerbated the bubbles in asset prices and the rapid build-up of debt that characterised the Nice decade. On the Nationwide measure, annual house price inflation averaged 12% over the decade. Meanwhile, household debt rose at an average annual pace of 11%. Public sector net borrowing was close to zero when Labour took power, but rose to £36.5bn or 2.5% of GDP by 2007/8. And of course we cannot forget the banking sector. The UK banking system's assets and liabilities exploded, from £2.5trn at the start of 1998 to a whopping £7trn by the end of 2007.

So even a return to "normal", where normal is some sort of long-run average, would mark a significant change for the economy compared to the last decade or so. Admittedly, overall economic growth would be only a touch weaker than in the recent past. However, the balance of growth would look significantly different. Meanwhile, house prices would increase broadly in line with average earnings at between 4% and 5% per annum. Share prices would increase in line with overall nominal GDP growth. And debt would remain broadly constant as a share of GDP.

Or back to the '90s?

A return to "normal" is perhaps the least we should expect, though. In fact, we could see a much more fundamental change than this.

The obvious template is the early to mid 1990s, when the UK was last emerging from a recession. After all, during the "Lawson boom" of the mid to late 1980s, GDP growth was just as, if not more, unevenly balanced than growth over the past decade. Other parallels with the current situation include a housing market that became seriously overvalued, a sharp drop in the household saving rate and the opening up of a large current account deficit.

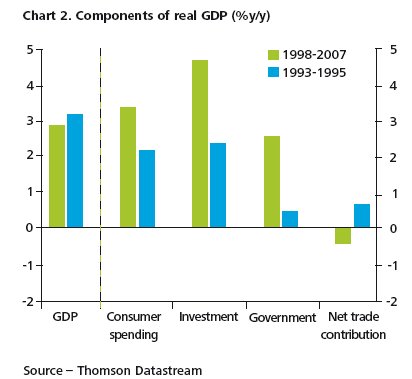

Although the economy began to expand again in 1992, it was not until 1993 that economic growth began to look relatively healthy. Accordingly, Chart 2 shows the shape of economic growth for the three years between 1993 and 1995. If this were the pattern of growth that we were to see over the next decade, the differences with the past few years would be pretty striking. Consumer spending in the mid-1990s, for example, under-performed overall GDP growth – in sharp contrast to the recent pattern. Government spending was even weaker. Yet net trade provided an average annual contribution to growth of some 0.7%.

History repeating itself?

Of course, history need not necessarily repeat itself. Nonetheless, there are likely to be some big similarities between the situation back then and the situation the post-recovery UK is likely to find itself in.

The first is the sharp fall in the exchange rate seen in both cases. The sterling trade-weighted index has now fallen by about 27% from its peak, an even bigger nominal drop than the 17% fall seen after the UK's exit from the ERM in 1992. In real terms, the falls are broadly similar in magnitude. (See Chart 3.)

Of course, the fall in sterling might yet be reversed. But a full reversal is unlikely, given that the pound is now trading broadly in line with its fair value. In this article, we assume that the drop in the pound is more or less sustained.

The second common factor is the intense pressure on the Government to contain its spending in order to bring down its borrowing levels. Between 1993 and 1995, government spending was growing, but an average annual rate of just 1.9%. Spending then fell by 2.2% in 1996/7 and by a further 0.6% in 1997/8. (See Chart 4.)

The Government will have little choice but to impose as tight, if not tighter, controls on spending this time. After all, the chart also shows that we expect public sector net borrowing to peak at an even higher 16% or so of GDP during this recession, compared to a peak of 7.8% in 1993/4.

Whichever party is in power after the next election will therefore have to make eye-wateringly tight spending commitments, on top of significant tax increases. At the very least, we expect the Government to freeze overall spending in real terms for several years. And significant real cuts in spending are more than likely. Of course, actually sticking to the promises is a different matter from making them. However, the Government may have little choice but to do so. And in the mid 1990s, this is exactly what both the Conservative and Labour Governments did.

That said, there is one factor which clearly makes this post-recovery economy rather different from that seen in the mid 1990s, or indeed after any other recessions – namely the legacy of the credit crunch and the bursting of the asset price bubbles.

A return to the days of "easy money" is pretty much out of the question, with firms and households finding it permanently harder to access bank borrowing. But firms and households may be less keen to borrow anyway. They could be trying to pay down their existing debt for years to come. After all, we think that around one quarter of mortgage holding households could end up in negative equity by the time house prices have bottomed out – compared to between 10% and 15% of households in the early 1990s.

Admittedly, interest rates are likely to remain at relatively low levels by historical standards, keeping interest payments fairly low relative to income and profits. But with high inflation no longer eroding the real value of debt, debt repayments now make up the bulk of household debt servicing costs.

The new world

So what will the economy of the next decade look like? Overall economic growth could actually be fairly volatile. A further period of weak or negative economic growth is likely to be followed by several years of relatively strong growth as the large amount of spare capacity in the economy is used up.

On average, though, economic growth could be fairly similar to the rates seen in the past decade. In other words, there is little reason to expect the underlying or trend rate of economic growth to have changed much. Admittedly, the boost to the labour force from rising net migration has now largely run its course. Equally, however, trend productivity growth could receive a significant boost from shifts in the composition of growth. (We will return to both of these issues later).

Indeed, the shape of growth could be virtually unrecognisable by recent standards. For a start, government spending will be stagnant or falling in real terms.

Consumer spending won't perform quite as badly as this, given that house prices will probably be rising (albeit just in line with average earnings) and interest rates will still be pretty low by historical standards (assuming, of course, that quantitative easing does not go hideously wrong). And inflation will also remain low (ditto).

Nonetheless, after a decade during which consumer spending outpaced overall economic growth, it would not be surprising now to see a decade where consumer spending underperformed – particularly if the process of paying down debt is drawn-out and if the likely rise in taxes falls on the consumer sector. We have assumed sub-trend growth in consumer spending of 2% or so per annum.

Investment could be rather stronger, as firms use the recovery in their profits to build up their capacity. But the real star of the show is likely to be the external sector. Admittedly, concerns have been voiced about whether the UK's manufacturing sector is big enough to provide a significant boost to net trade. Manufacturing made up just 12.7% of the economy in 2007, a share which is likely to shrink this year to around 11%.

However, we see no reason why the manufacturing sector cannot see a mini-revival and rebuild its capacity to bring a temporary halt to, or even partially reverse, its long-run downward trend. After all, other mature economies have a much bigger manufacturing sector than the UK. In France, manufacturing accounted for 15% in the economy in 2007 (the latest data available). And in Germany, it accounted for some 24%. (See Chart 5.)

Even if we are being too hopeful about the manufacturing sector, the drop in the pound could give a significant boost to services exports. Admittedly, the UK's biggest services exports (around one third) are financial services and they look unlikely to grow much. But tourism accounts for a further 12% of services exports and the number of visitors to the UK rose at double digit annual rates following the 1992 sterling depreciation. Other services exports which could benefit include the freight services offered by shipping operators and consultancy services such as advertising, architectural and legal services.

What's more, the drop in the pound should also improve the UK's trade position by reducing demand for foreign imports. For example, not only will more foreign tourists come to the UK, but more UK residents will take their holiday at home rather than abroad. Taking all of this into account, we think that net trade could easily contribute around 1% per annum to GDP growth. Just closing the trade in goods and services deficit would boost GDP by 3%.

The winners and losers

Charts 6 and 7 show how these different patterns of growth might affect the relative size of different sectors in the economy. Chart 6 shows the breakdown of the UK economy in 2007 (the latest data available) and Chart 7 shows how it might look in 2020. The services side of the economy is shown in blue, the industrial side in green.

The manufacturing sector could see a fairly significant rise in its share of the economy. We think that it could increase to 13% or even 15% (requiring average annual growth in manufacturing output of around 6% and 8% respectively). Business services are likely to see an increase in their share too, from 24% to approaching 30%.

In contrast, the financial sector is likely to see its share of the economy shrink. Banks themselves are likely to retain a cautious attitude for years to come. Even if their risk appetite does return, an overhaul of the regulatory system is likely to restrict severely what they can do. Amongst the various recommendations in the Turner review of global banking regulation published in March were the increased reporting requirements for unregulated financial institutions such as hedge funds and higher levels of capital to support risky trading activity. Alistair Darling has also openly supported the idea of a new European Union framework for financial regulation. If output in the financial services sector stagnates, its share could shrink to just 5% or so of GDP.

Similarly, stable output in the public administration, health and education sector would shrink its share of the economy from 18% to just 12%. Meanwhile, the relatively slow growth of consumer spending compared to overall GDP suggests that the share of the consumer services sectors in the economy (i.e. distribution and hotels/restaurants) might also drop back modestly.

We assume that most other areas of the economy (namely transport/communications, construction, energy supply and other services) grow broadly in line with overall output.

A closer look

This is still very much a broadbrush picture of the economy. What if we drill a little deeper?

Some of the most significant developments could be seen in the manufacturing sector. The drop in the pound should clearly help the UK play to its traditional exporting strengths – such as the production of aircraft, pharmaceuticals, engines, high-tech IT equipment and electrical components. But by making imports less competitive, the drop in the pound could have an even wider impact by encouraging UK manufacturers to produce more of the goods and services which have previously tended to be imported.

The car industry, in particular, could do well. Chart 8 shows that transport equipment, including vehicles, accounted for 20% or £54bn of goods imports in 2007. More of this vehicle production may now be shifted to the UK. Assembly plants tend to be shifted from country to country fairly regularly depending on where costs are lowest. And even for those cars that are still put together abroad, the UK can produce more of the component parts.

Another 19% of goods imports are accounted for by electrical and optical equipment. It is perhaps hard to see the production of basic office equipment shifting back to the UK. But the UK could start to produce more of the high-tech goods that it needs, such as medical precision equipment. Meanwhile, environmental concerns about flying food around the world might also reduce demand for food imports.

In contrast, the drop in the pound is unlikely to halt the continued decline of some of the UK's traditional manufacturing bases – such as textiles. And the UK's North Sea oil sector could dwindle away as the UK's oil and gas reserves are depleted.

Meanwhile, we think that the services sector is particularly fertile ground for new or nascent types of services to spring up and expand. The provision of regulatory and advisory activity related to "green" or environmental issues is yet really to take off. Yet more and more of companies' time and resources will be devoted to complying with environment legislation and new green taxes. And firms will need to be increasingly advised on how to incorporate these green issues into their mainstream corporate disclosure.

Meanwhile, the online sector could also expand into new areas. A few years ago, no-one would have guessed that people would be buying their music or postage over the internet, for example. The shape of consumer-facing industries could therefore continue to change quite significantly, with the role of the high street declining further. We also doubt that we have reached the limits of what supermarkets can offer – as their venture into providing financial services underlines. We could yet see Sainsbury's restaurants or Tesco gyms attached to the stores.

As people get richer and can afford to pay more for convenience, we should also expect a greater provision of personalised and time-saving services. We already have supermarket home-deliveries, personal trainers and companies that will book you a restaurant and pick up your dry cleaning. Why not personal chefs? Could granny-minders become as common as child-minders? Related to this, the ageing population is likely to give rise to continued growth opportunities in sectors related to old-age care, such as nursing homes.

Lastly, technological advances could provide a whole host of opportunities that we can barely imagine. Of course, by their very nature, we do not know what they are yet! But areas such as biotechnology, robotics and energy conservation seem particularly promising in this respect. During a recession, it may be hard for innovators to get firms to buy and develop their technology. But in the post-recovery economy, these discoveries could be quickly and widely adopted.

The regional implications

Clearly the changes in the sectoral composition of the UK economy will have crucial knock-on implications, not least on the regional picture of the UK. Perhaps most obviously, it has been suggested that the demise of the financial sector will be devastating for London. However, we think that these concerns are somewhat overdone.

Of course, there is no denying that London is more heavily reliant on financial services than the rest of the country. But the sector is perhaps not quite as important as is commonly assumed, accounting for just 16.5% of the region's output in 2006 (the latest data available), compared to between 4% and 8% in other regions. (See Chart 9.)

What's more, only a fraction of those financial services are the wholesale or City-type services that will suffer the most serious long-term damage from the credit crunch. We think that City-type financial services account for only one quarter of financial services in the UK as a whole. Even if all of these were located in London (which they are not, given the growing financial centres in cities like Edinburgh and Leeds), they would still account for only 10% of London's economy.

Meanwhile, London is set to remain a world leader in a host of other fields, from accountancy to the arts. The drop in the exchange rate is only likely to reinforce London's position by making it cheaper for international firms to locate in the UK. Similarly, London seems wellplaced to be at the forefront of the creation of the new areas of strength, such as "green" advice. In fact, it is not obvious that London's share of the economy has to shrink at all – it could even continue to grow.

Equally, however, those hoping that the manufacturing revival will mark a sea-change in the fortunes of the relatively industrialised regions of the north might be disappointed. Regional disparities are far smaller than they used to be, in part because many northern regions have successfully built up their services sectors in order to compensate for their declining manufacturing bases. Chart 10 shows that even in the most manufacturing dependent regions, manufacturing accounts for less than a fifth of output.

Nonetheless, some regions will still benefit from a growing manufacturing sector more than others. Chart 10 shows that the North, Yorkshire, the Midlands and Wales are those regions with the biggest manufacturing sectors relative to the size of their regional economies.

Perhaps the biggest driver of regional change, however, could be the slowdown in public sector spending growth. The effects of this spending is perhaps most visible in the labour market. Chart 11 shows that some 29% of employment in Northern Ireland is accounted for by the public sector – compared to just 17% in the East and South East.

However, we doubt that the regional shifts will be on anything like the scale seen during the de-industrialisation of the past few decades. What's more, even those regions which fail to keep pace with the overall UK economy might see some benefits of this. If London's share of the economy did slip, most London residents would welcome an easing of the pressure on its creaking infrastructure.

Labour market changes

The changing shape of the economy is also likely to involve pretty significant changes in the shape of the labour force.

On the face of it, there could a significant skills mismatch, as demand for labour in the public and financial services sectors wanes and demand for manufacturing labour increases. However, the labour mismatch is perhaps not as severe as it might look. After all, the manufacturing sector is not the sole preserve of the blue-collar manual worker that it once was. According to the Work Foundation, the "better educated" rose from 1% of the manufacturing workforce in 1970 to 13% by 2005. Office of National Statistics data show that almost 20% of manufacturing employees hold degree level qualifications.

What's more, the shifts in the economy could in fact improve the productivity of the labour force, given that manufacturing is inherently more productive than the services sector. Chart 12 illustrates how manufacturing productivity growth has outperformed productivity growth in the economy as a whole for almost all of the past twenty years. This is because manufacturing lends itself more easily to automation and technical progress than the services sector, which is more labour-intensive.

The other main change in the labour force is likely to be much lower levels of net migration than those seen over the past decade. The official data show that net migration doubled in the latter part of this decade, and even these numbers are likely to be a gross underestimate of the true extent of migration. (See Chart 13.)

Net migration surged after the expansion of the European Union in 2004. Not only were large numbers of immigrants entering the UK, but relatively few were leaving the UK, given that they generally came with the intention to work for at least a few years. Now, however, we have reached the stage where some of these immigrants are starting to return to their home countries. Even if inflows of immigrants remain strong, then, net migration is likely to be much lower.

But inflows of immigrants could easily fall too. The lower level of sterling against currencies such as the Polish zloty (even after the recent depreciation in Eastern European currencies) will permanently reduce the repatriated value of migrant earnings. Meanwhile, other European countries will have to open their borders over the course of the next few years, once the temporary restrictions on the movement of labour from the accession countries expire. They are thus likely to attract immigrants who would otherwise have come to the UK.

Positive impact on the income distribution?

The changes won't stop there. Discussing them all is beyond the scope of this piece. But we think that there are a couple more worth mentioning.

First, firms' requirements in terms of property and capital goods will change. Demand for industrial property will increase relative to demand for retail space, for example. This could have crucial implications in turn for the relative performance of different areas of commercial property.

Second, it is possible that the distribution of income becomes more compressed. Research by the Institute of Fiscal Studies shows that income inequality remains at historically high levels. However, pay growth of the highest earners is likely to be rather more restrained over the next decade than the last. Not only will increased financial regulation include limits on financial sector bonuses, but tax increases could be concentrated on the highest earners (the Conservatives have said that they will not reverse the increase in the top rate of income tax from 40p to 45p that Labour plans to introduce).

Conclusions

While we should not underplay the enormity of the economic and social costs of the current recession, it is all too easy to get caught up in the present and to forget that a world beyond the credit crunch does exist. And any business planning for the future needs to bear these longer-term developments in mind too.

Equally, though, it would be misleading to talk about when things "get back to normal". After all, what is normal? It could mean how the economy was before. But what's certain is that the economy over the next ten years will look significantly different to the economy of the last ten years. Many things that we have taken as given – from a declining manufacturing sector to a burgeoning role of the state – could now be turned on their head. The UK economy is in a constant state of flux – and the next decade will be no different.

To view this document in its entirety please click here

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.