As the recent financial crisis continues to reshape the global financial services industry, there are many institutions who are viewing this as an opportunity to 're-invent' the way they do business. These institutions are examining what structural changes their business will require in future, what long-standing business processes need updating to meet the new market reality, and what legacy systems are in need of an overhaul. They are also examining their strategic direction, deciding what markets they want to compete in, and even challenging the type of financial institution they should be categorized as.

One key element of this business 're-invention' is to carefully consider the tax impact of each of these market driven changes. For example, acquisitions or divestments can have a significant impact on the tax efficiency of an organization – particularly the utilization of recent tax losses at some business units – and this impact needs to be taken into account before executing any deal. Tax considerations should also be part of any operational redesign, with plenty of opportunity to update transfer pricing models to the new environment, or to further integrate tax reporting into finance transformation programs. Finally, tax issues also need to be included as institutions reshape their talent strategies, particularly in their approach to executive compensation.

As the financial landscape continues to change, Deloitte's Global Financial Services Industry network is committed to providing continued thought leadership, surveys and studies on the issues most important to global financial institutions. Deloitte's aim is to help guide clients through these challenging times and provide them with insights useful in not only surviving the credit crisis, but essential for clients to continue 'Thriving in a changing environment'.

Ellie Patsalos

Leader, Global Tax Financial Services Industry

TAX LOSS UTILIZATION - UNDERSTANDING THE UPSIDE OF LOSSES

The current global financial crisis has left many financial institutions awash with losses. However, the ability to utilize these losses against future profits requires careful consideration of local tax codes and an understanding of the time-sensitivity of many of these tax losses.

The current global financial crisis has left many banks and other financial institutions awash with losses. It might be concluded that all will be plainsailing for the tax department in the years to come as huge losses incurred through the downturn are offset against potentially more modest profits, when the markets eventually start to recover.

This could be a costly conclusion; now is not the time to turn attention away from tax. But what action should the CFO be taking? Where should the tax department focus its resources? How should it measure its contribution and results in an environment where the Effective Tax Rate (ETR) is becoming less relevant for many companies?

No company can assume that the tax benefit of its operating losses is a foregone conclusion. The CFO and tax director should be ensuring that book losses are flowing through to the tax returns. Both permanent and temporary or timing differences should be understood and managed and all action should be taken with a view to maximizing the company's ability to efficiently utilize losses as the business recovers. In times of falling profits and shrinking revenues tax authorities will be seeking to replenish public coffers more than ever. A UK think tank, the Centre for Economics and Business Research, recently put the loss of tax revenues for the UK Treasury from the financial sector at GBP28bn for the coming year.1 Members of the Joint International Tax Shelter Information Center announced at the start of this year their intention to work together to prevent manipulation of tax losses by large banks and other businesses as they fear that new and innovative ways of using tax losses will deprive them of further tax revenues.2

It is absolutely essential in this environment that tax losses and similar tax attributes are managed in real time, to minimize risk of forfeiture and maximize current and future benefits. In order to do this, tax should be considered at the start of the decision-making process throughout this defining period.

Restructuring the business

Many companies are re-examining the way they do business, determining the core successful business and restructuring to focus on these areas. A takeover or a major change in shareholders (say, arising through a merger of businesses) may limit a corporation's ability to utilize losses incurred prior to the transaction. Moreover, internal restructuring alone may be sufficient to threaten available tax losses in some jurisdictions or across multijurisdiction operations. At the simplest level, the future use of losses arising in respect of a specific business may be lost or badly limited in certain jurisdictions if that business is terminated, even if the group as a whole continues to trade. Consolidation of businesses, intended to reduce costs, may also put tax losses at risk.

In profitable periods, loss restriction rules may not have been considered in any depth in internal reorganizations, but during periods of large losses – precisely the time when groups are now likely to undertake major restructuring – these rules must be considered carefully within the cost/benefit analysis of any business model. The CFO will need to ensure that tax is considered in the early stages of any reorganization.

Efficient loss utilization

To fully understand the impact on losses, the CFO must ensure that the tax department is involved in business planning and forecasting. It is all very well to protect a loss from inadvertent forfeiture at the time of a restructure, but if significant losses become trapped in an entity or jurisdiction where the business has been restructured to limit future risk and therefore future profit, it may be years before the benefit of these losses can be fully realized. In a few jurisdictions, losses do not have a shelf life; in many more jurisdictions, though, losses may expire if not used within a fixed period.

One of the most effective ways to obtain a benefit from tax losses is through carry-back against prior year profits, if available. This may give certainty of use and result in a tax repayment rather than a benefit at some time in the future. Such a strategy may require a rethink of priorities and change in tax department behavior. Early filing of returns may allow early repayment of taxes and tax department resources should be refocused accordingly. Helpfully, some tax authorities are acting to assist early repayment of taxes. The 2009 Singapore Budget, for example, includes temporary enhancements to the loss carry back regime, including allowing provisional claims for tax refunds to be based on estimated losses rather than finalized assessments.

Where tax losses cannot be immediately utilized, businesses need to consider the extent to which losses carried forward can be recognized for accounting purposes, as well as the value that regulators might put on deferred tax assets representing loss carryforwards. The lessons of the Japanese banks in the "lost decade" should be remembered. A stark example of the risk attaching to losses was the government rescue of Resona Bank in May 2003, following the bank's auditors refusing to recognize more than three years of deferred tax assets.

Corporations cannot afford to risk a challenge from auditors who must consider these assets with ever more caution, and banks and other similar institutions might evaluate if there are transactions pursuant to which deferred tax assets might be replaced with other assets. More recently, the size of deferred tax assets included within the regulatory capital of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were widely debated when the US Treasury and Federal Housing Finance Agency seized control of these entities last year. While it has always been important, tax accounting has rarely had a higher profile.

Tax vs. Book

Even assuming all tax losses may be recognized for accounting purposes, there may be significant differences between book and tax losses. The Board needs to be aware that a loss that has crystallized in the books of the business may not necessarily be triggered for tax purposes in the same period and therefore may not be available for utilization. Many countries will not allow a tax deduction for provisions or reserves; it is only when the loss is realized that the deduction may be taken and even then, some countries might impose onerous restrictions before write offs are allowed.

This may result in material book tax differences. CFOs and tax directors should be making sure that their Board knows exactly the type and size of book losses that will not result in a tax loss and at what point a tax loss may be triggered. This should not come as an unpleasant surprise during financial reporting, or worse, when cutting a cheque for the taxman.

The tax department needs to have good systems in place to monitor differences between book and tax losses and changes in the accounting and tax treatment of these losses in different territories. Maximizing tax losses may be too simplistic a target, it is efficient utilization that should drive strategy. The rules for utilizing tax losses in the period in which they arise may be more flexible. Losses carried forward, however, may be restricted in use; they may, for example, be restricted to a percentage of profits, or expire after a specified period. In certain circumstances, it may in fact be beneficial for losses to be deferred where possible, and triggered only when they can be effectively used.

Those tax losses that cannot be recognized for accounting purposes should not necessarily be forgotten. A corporation's unprovided losses may yet be available for use as forecasts change, and protection of these losses should be no less closely monitored. Some companies are actively compiling potential tax planning strategies and techniques to increase the benefit of losses sustained but not recorded. As the review and analysis of these transactions is completed, it might be possible to increase the benefits recognized for financial statement purposes.

Tax credits ... or are they?

Although the discussion so far has focused on taxes on profit, it is important to remember taxes withheld at the source. These will often continue to be levied regardless of a business being in a loss-making position, as they are calculated and withheld on gross income (interest, dividends), rather than profit. Previously, withholding taxes may only have been considered a cash flow disadvantage for many profitable businesses, as these taxes could generally be credited against the main corporate tax liability. However, where there is no corporate tax liability due to losses, there may be a real and full tax cost arising from withholding taxes. Businesses should therefore be examining taxes withheld at source and ensuring these are minimized where possible.

Efficiency in this area cannot be achieved by the tax department alone. Whether tax is deductible at source will depend on the exact nature of the contract or transaction entered into. A product structured to achieve a return by way of interest income may be subject to withholding tax, whereas a product providing a gain or loss on maturity may not. Therefore client-facing management must be educated in this area and effective withholding tax management included within commercial targets.

Aligning transfer pricing

Transfer pricing is not just a stick for tax authorities to beat businesses with in times of profit, it can also be used to challenge losses, both in absolute terms or in the relative allocation of losses on a given transaction amongst group participants. With the unprecedented speed with which markets are changing, it is vital that transfer pricing models are re-examined to ensure they are not based on pricing models that are no longer relevant. The CFO and tax director must ensure that the group's transfer pricing keeps pace with developments in the market or either risk lengthy disputes with tax authorities further down the line or risk missing out on opportunities to ensure tax efficiency today. Data previously used to benchmark transactions and results, or transactions previously considered comparable, may be unreliable and out of date. Moreover, with increased potential regulation may come new increased disclosures about financial transactions and results, so tax directors may have to consider data from new sources to evaluate the arm's length result.

It is crucial that the CFO supports the tax department to drive changes in transfer pricing policy to ensure internal pricing keeps pace with external. In recent years, transfer pricing models may only have needed minor annual adjustment, now they may require wholesale review. Is the return to capital still sufficient, given the increased risk evident in the market today? Should banking groups which are increasingly charging significant fees to external customers be replicating this with group entities? Should interest rates be aligned to ratings of individual borrowers, or should guarantee fees be considered? There are many new questions to be answered about intercompany funding and treasury functions.

A thorough review of the group's transfer pricing policy now, in conjunction with commercial management, should not just protect against future challenge by tax authorities, but provide an opportunity to ensure that losses are efficiently utilized as the business recovers.

The opportunities

In the current environment, some entities will have considerable losses, and some will have losses so substantial that they will have significant valuation allowances raised against those losses. Therefore, the profit on a transaction will be treated in one of three ways:

1. Profitable companies will recognize a tax expense in their financial statements and pay cash tax.

2. Loss companies that do not have any valuation allowance will still recognize a tax expense in their financial statements (reducing NOLs), but will not pay any cash tax.

3. Loss companies with a large valuation allowance (a "Deep Loss company") will neither recognize any tax expense (as the NOLs are not recognized as assets), nor will they pay any cash tax.

Therefore, when evaluating any potential transactions, a Deep Loss company would enjoy a larger gain on the bottom line than a profitable company assessing the same transaction and can afford to make a lower pre-tax profit than a profitable company, while still enjoying the same, or better return below the tax line.

In general, most front offices are compensated on a pre-tax basis, and as such, the potential benefit highlighted above may be missed. However, analysts use post-tax numbers in analyzing performance, and as such, any benefits that can be received through exploiting the above should have a positive impact on the share price.

Now may also be the time to consider the internal restructuring that was commercially desirable, but previously considered tax inefficient. Transactions to achieve internal efficiencies that may previously have been put on hold due to potential for triggering taxable gains or profits on fair market value transfers, should now be revisited. These gains may be significantly reduced or eliminated in the current environment and now may be the time to reconsider the corporate structure.

Conclusion

Although ETR has been a useful tool for monitoring whether tax was being efficiently managed, it should never be the only measurement. Other key performance indicators that have perhaps been considered less important should now be re-examined. Effective tax management for a loss making business must be measured over an extended period to determine effectiveness. It is not simply a matter of making sure tax and book losses match, and in fact this may not always be efficient. Quick wins such as loss carry-back should be implemented swiftly where possible, thus providing a more immediate cash benefit.

The eventual ability to use tax losses is key, and the importance of minimizing the risk of future challenge by tax authorities cannot be underestimated. Tax risk is as great an issue now as during high tax-paying periods.

Finally, the tax opportunities available to businesses during a loss period, such as the potential to implement stalled internal restructure plans, should not be missed. As such, it remains as vital as ever today that tax departments ensure that they keep the focus of their CFOs, and that CFOs consider how best to monitor and evaluate their tax departments.

ACQUISITIONS AND DIVESTMENTS THE TAX IMPACT OF RAPID RESTRUCTURING

Given the enormous impacts of the current financial crisis many financial institutions have already begun significant restructuring programs to help restore them to profitability. However acquisitions, divestitures, and other capital raising activities can have a major impact on the tax efficiency of an organization.

In recent months we have read a great deal about how many banking groups are going through divestment and restructuring programs with a view to restoring investor confidence and enabling a return to sustainable profitable business models. Recent examples include Citigroup in the US and RBS in the UK who have both announced significant divestment and restructuring programs.3 As a result, tax departments will be concerned with the management of these divestment and restructuring programs and ensuring that these programs are executed in a tax efficient way. Furthermore, it will also be important for banks to understand the tax issues associated with any participation in government financial stability schemes.

Acquisitions

Over the last 12 months there have been a number of high profile acquisitions involving US and European banking groups. This in itself has brought particular challenges and placed additional resource demands on bank tax departments.

Tax strategy and governance will need to be developed for the enlarged banking groups including stakeholder communication, tax risk policy, key performance indicators and tax group organizational structure. Tax departments will also need to support the business in post acquisition restructuring and integration as well as the disposal of non-core assets. This is in addition to the normal responsibilities of the tax department in supporting the business, ensuring that all statutory and compliance deadlines are met and dealing with tax accounting matters as part of the post acquisition reporting process.

Capital raising

A number of the key US and European banks have issued new capital to improve regulatory capital ratios and much of this capital has been subscribed by governments or other new investors rather than existing shareholders. This has led to a number of banking groups undergoing a change of ownership for tax purposes which has led, or may lead, to restrictions on the availability of tax losses carried forward. The definition of a change in ownership and impact of these rules will vary by jurisdiction. We understand that US banks are currently lobbying for an exemption from the US tax rules that restrict losses on a change in ownership if that change in ownership has been caused by US Government funding. Furthermore, the US has issued guidance as recently as October on the applicability of loss utilization on instruments acquired by Treasury under the Capital Purchase Program.

Good bank/Bad bank

Against the background of acquisitions and capital raising a number of banks have started to implement restructuring and divestment strategies and the term 'Good bank/Bad bank' has been used in this context. In a broad sense a Good bank/Bad bank restructuring involves the separation from the Good bank of 'toxic' assets (or assets where there is significant uncertainty over valuation) into a separate Bad bank. This separation could be a virtual separation for internal and external reporting purposes or could involve the creation of a separate Bad bank vehicle. The assets that are separated out into the Bad bank could also include assets or businesses that are not toxic but have been identified as being non-core. In any variation it will be important for banks to understand the tax issues associated with implementing a Good bank/Bad bank reorganization strategy. For example, achieving tax neutrality on intragroup transfers to a Bad bank entity in the current environment may be more about securing effective tax relief for losses rather than deferring unrealized gains.

In addition the ability to effectively utilize tax losses incurred by a separate Bad bank entity against profits of the Good bank will depend on the way in which the Bad bank is structured.

Asset Protection Schemes (APS)

One of the areas where new thinking will be required is in connection with assets to be covered by government financial stability schemes including the UK Government's Asset Protection Scheme. The UK Asset Protection Scheme is similar to schemes also announced in Switzerland and the Netherlands for example.

For all of these schemes it will be important to consider where the assets are currently booked and whether the assets will be placed into a special purpose vehicle or single group entity. In the case of a Good bank/Bad bank restructuring the assets to be covered by the APS are likely to be part of the Bad bank and it should be straightforward to match any guarantee or similar fee payable under the scheme with the underlying assets if the assets are in a separate Bad bank vehicle. However, if the assets to be placed into the scheme remain on the balance sheets of different entities throughout the group the analysis is less straightforward. We would expect the asset protection will be pushed down to the asset holding entities from an accounting and regulatory perspective possibly through the use of internal group back to back arrangements.4 Where the asset protection is pushed the guarantee fee would also be expected to be pushed down. Where the fee is pushed down to subsidiaries and foreign branches there may be challenges on deductibility of the fee and the transfer pricing arrangements from the relevant tax authorities.

Transfer pricing

The change in strategic direction by the banks towards core business areas and markets, increased focus on risk management, and a change in remuneration policy to align with this strategic change should also drive change to the group's transfer pricing approach and policies. Banking groups can expect challenges from tax authorities where assets are transferred from overseas jurisdictions or where overseas activities are closed as banks move out of non-core markets given the difficulty in collecting comparable market data. Where overseas branches are closed, banks may also be challenged on the profit attribution approach on the transfer of assets from the closed branches back to head office jurisdictions.

Disposal of non-core businesses and assets

As part of the restructuring programs banks may also be looking to sell non-core businesses and asset portfolios. Instead of structuring these disposals to minimize any tax costs, such as ensuring capital gains are realized tax free (e.g., under participation exemption regimes or similar), banks will be more likely aiming to secure value for tax losses attached to loss-making businesses and write downs on asset portfolios. In this respect conventional thinking on business and asset transfers will need to be turned on its head. For example banks may look to sell assets instead of shares as a way to realize value for tax losses and write downs as buyers will be reluctant to pay for tax losses given most jurisdictions have restrictions on the use of tax losses following a change in ownership.

Tax risk management

With an increased focus on risk management we would expect there will be an increased focus on achieving certainty on tax deductions for write downs, utilization of losses, and the tax treatment on acquisitions and disposals. Recent experience in the UK has been that HM Revenue & Customs are increasingly willing to engage in discussion on transactions on a real time basis given the current market environment.

Additional focus on taxation of banks

As a result of recent events there has been an increased focus on the regulation of banks including the use of off-shore financial centers and tax havens. In the UK, HMRC are expected to publish a draft code of practice on taxation for the banking sector, so that banks can comply with not just the letter but also with the 'spirit' of the law. The code of practice is expected to be published towards the end of April. It will be interesting to see how HMRC define the spirit of the law and what effect this will have on the way banks currently operate. It is unlikely that many banks would consider themselves as operating outside of the spirit of the law. When applying a particular statutory provision the UK courts generally take a purposive construction of the provision and therefore many tax planning schemes that go through the courts and that go against the purpose of the law fail. However, not all tax law has a clear purpose embedded in it (or at least, the purpose contended in court by HMRC). Where the purpose really isn't clear, where is the spirit? Additional scrutiny on entities operating in tax havens has been a high priority under the new administration.

Among the things being contemplated are the treatment of foreign corporations managed and controlled primarily within the US as domestic for income tax purposes, the imposition of new rules on transactions and entities involving "offshore secrecy jurisdictions", and a codification of the economic substance doctrine.

Tax capacity and tax accounting

Tax losses that become trapped as a result of a restructuring may not be available for a significant period of time or lapse entirely. Change in ownership and change in activity following a restructuring can also lead to the risk of losses carried forward being restricted. The ability to plan and manage the timing of deductions and jurisdiction in which deductions are realized is increasingly important in the current environment.

Issues around the recognition of deferred tax assets for losses have arisen particularly where activities have been discontinued as a result of business restructuring. The uncertainty over the level of further write downs and losses means that additional resources will continue to be required in forecasting tax capacity and in supporting the recognition of deferred tax assets.

Conclusion

Overall this is a very challenging time for bank tax departments, both in terms of resource requirements and the technical issues that are coming out of the current economic environment, and in particular with regard to banking divestments and restructuring.

COMPENSATION AND REWARD TAX TACTICS TO HELP KEEP TOP TALENT

The public and political scrutiny of financial institution bonus structures has put pressure on organizations to reshape their approaches to compensation. Tax burdens can have a significant impact on each of these new strategies and must be considered carefully before making a change to compensation.

Nobody can doubt the seismic changes affecting major financial institutions across the globe or the fundamental impact on the quantum and structure of executive compensation.

These changes come from a combination of factors:

- Plummeting revenues, profits and share prices which reduce the capacity of major organizations to raise pay levels while fall in equity values has further undermined the total compensation being received.

- Greater governmental ownership and asset protection have created political pressures for more regulation in affected organizations.

- Legislation that has placed restrictions on the deductibility of payments and the ability to design flexible arrangements.

- A concern that the "bonus culture" has contributed to the economic crisis through encouraging and rewarding undue risk taking.

Compensation trends

The impact on executive compensation remains to be seen, but is likely to include:

- Reduced emphasis on short term bonus reward.

- More long term awards linking the delivery of compensation to demonstrable long term value creation.

- Recognizing the cost of risk in the composition of compensation.

- Reduced acceptability of short term tax based structuring.

- Where there is government funding, ongoing controls and reductions in compensation levels until that funding is reduced.

- Greater reluctance to defer compensation on a voluntary basis.

Tax impacts

This article is concerned with the likely implications for tax structuring for executive compensation. The effects on tax thinking and the related structuring of compensation will be profound and will need to be factored into the thinking of shareholders, boards and remuneration committees at an early stage.

In this article, we will consider the likely effects in the US and the UK. It is expected that similar issues will be seen in other countries.

United States

Recent changes have impacted the US tax system for both individuals and corporations and there is an expectation that individual tax rates will increase.

Current tax features

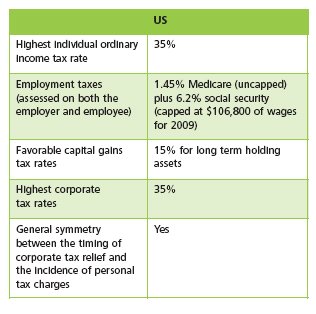

Some headline features of the US system which arerelevant to compensation include:

Likely trends

There is already an impact on the level and delivery of compensation and further restrictions as part of the government assistance programs will force further change.

Government assistance

The Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) is a program of the US government to purchase or insure up to $700bn of assets and equity from financial institutions. Recent legislation enacted places new restrictions related to compensation paid to top executives of companies receiving financial assistance from TARP.

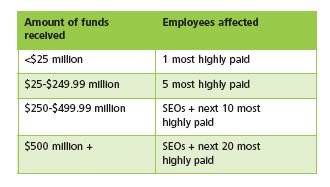

These will be applicable to the highest-paid employees and the Senior Executive Officers (Proxy Listed Officers) based on the following schedule:

For affected executives, the only incentive compensation permitted in the future will be long-term restricted stock which:

(1) Does not fully vest while the company has an "obligation arising from financial assistance" under TARP.

(2) Is capped at one-third of the employee's total annual compensation.

(3) Is subject to other terms that the Secretary of the Treasury deems to be in the public interest. In addition, any institution participating in TARP is subject to and must certify compliance with the following provisions:

- Treasury Secretary review of all 2008 compensation paid to the SEOs and 20 next most highly paid executives ("Affected Executives") with reimbursement sought for any payments ruled to be "inconsistent with the purposes of TARP" or "otherwise contrary to the public interest".

- A $500,000 deduction limitation (instead of $1 million) for all SEOs and publicly traded entities regardless of when the compensation is paid with no exception for stock options or other performance based compensation.

- Mandatory "clawback" of any incentive compensation paid to Affected Executives based on criteria found to be "materially inaccurate"

- A prohibition on "Golden Parachute" payments to SEOs and 5 next most highly-compensated executives for departure for any reason, except for payments for services performed or benefits accrued.

- Company policy relating to approval of luxury expenditures will be required.

- An annual, non-binding, shareholder "Say-on-Pay" vote.

- A prohibition on SEO compensation that includes incentives to take "unnecessary and excessive risks".

- A prohibition on compensation that encourages manipulation of earnings.

- The compensation committee of the board of directors must be made up solely of independent directors (although the board can act as committee for private entities and those receiving $25 million or less in funds).

Previous attempts to limit compensation paid based on tax penalties and requiring performance based compensation have had limited success. They have resulted in gross-up payments on excise taxes and companies foregoing deductions. It will prove challenging to design programs with the traditional purposes of attracting, retaining and motivating key talent. It remains to be seen whether high performers will be reluctant to seek other employment and will be willing to work for less in this difficult period of time as argued by some proponents, or if employees will seek opportunities at companies that are not subject to the restrictions.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.