INTRODUCTION

Although US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) enforcement actions related to financial fraud and issuer disclosures have been on a decline since 2007, recent statements and actions suggest that the SEC is likely to re-focus its efforts on detecting, pursuing, and preventing accounting fraud.1 Since her confirmation as Chair of the SEC, Mary Jo White has made it clear that her administration will focus on identifying and investigating accounting abuses at publicly-traded companies.2 Among the recent initiatives announced by the SEC are the increased focus on the whistle blower program and the establishment of the Financial Reporting and Audit Task Force, the Microcap Fraud Task Force, and the Center for Risk and Quantitative Analytics.3

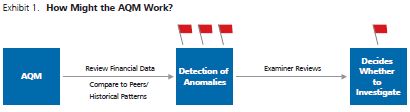

This paper will focus specifically on the Accounting Quality Model (AQM),4 one of the tools that the SEC will utilize in the automated detection of fraudulent or improper financial reporting. This may well shift the SEC's regulatory approach to increasingly incorporate the detection of potential accounting issues at earlier stages, prior to more rigorous examinations by the SEC. While it is unclear how the SEC might proceed after applying these first-stage screens, existing regulatory guidelines suggest that the theoretical economic impact of any potential accounting issues will be one important criterion in the mix of information considered by the SEC.

Consequently, companies would be well advised to anticipate SEC questions and identify anomalies in their financial reporting (defined in this context as unusual changes in financial accounting data and/or accounting treatments, which may or may not reflect a misstatement). Developing an understanding of the theoretical economic impact of any potential reporting anomalies will also be important.

THE IMPLICATIONS OF AUTOMATED DETECTION IN SEC ENFORCEMENT

Recent Developments Suggest that the SEC's Enforcement Strategy May Target Micro-Level Financial Accounting Anomalies

In April 2013, Craig M. Lewis of the SEC's Division of Risk, Strategy, and Financial Innovation discussed the SEC's AQM, which is a "set of quantitative analytics modeling tools that the SEC is designing to review filings."5 This Accounting Quality Model will "search for financial statements that 'appear anomalous' and will automatically flag them for review by an examiner." Lewis described this model as an attempt to "identify firms which have made unusual accounting choices relative to their peer group."

While the SEC incorporated the detection of accounting anomalies as part of its past enforcement efforts, a shift to automated detection systems alters the landscape on a fundamental level. With the sheer number of filers, a systematic approach to screen for financial accounting anomalies cannot easily be implemented without the aid of computerized automation. The SEC has always relied upon company or industry-specific developments as an important enforcement tool, but with the AQM, the SEC has implicitly indicated that identifying problems at an earlier stage will be a priority.

With the advent of an automated detection system, a statistical anomaly in a company's financial statements – whether or not it represents a potential reporting error – may trigger scrutiny by regulatory authorities prior to more overt and clear evidence of a problem. In effect, the SEC is actively developing the capabilities to cast a wider net at the first stages of any efforts to detect financial accounting anomalies (in part, by screening financial reporting data as it is filed). As a result, it is important for companies to assess and anticipate what the SEC will consider to be red flags potentially warranting further investigation.

Quantifying the Economic Impact of Accounting Anomalies May Well Play a Crucial Role in Assessing What the SEC Will Consider to be Red Flags Warranting Investigation

After employing first-stage detection algorithms, the SEC would need to decide which potential financial accounting anomalies warrant further investigation. Some may be false positives (i.e., have a legitimate explanation), others may represent unintentional reporting errors, while still others might indicate financial reporting fraud. As part of the AQM process, the SEC should assess the probability that a particular anomaly is suggestive of fraud. That is, not all anomalies have the same implications.

There are a number of reasons that the SEC might pay closer attention to financial accounting anomalies that have a greater economic impact. First, with limited resources, the SEC will not find it effective to follow up on every potential accounting anomaly uncovered by its initial screening process. Second, it would be incorrect to assume that the SEC would ignore the hypothetical "accounting fraud with a small economic impact." The fact that most financial reporting fraud is motivated by factors that will likely have a substantial effect on the real or perceived value of the company means that the SEC might consider a larger economic impact to be correlated with fraud, which could warrant a greater degree of scrutiny.

Excerpt from Codification of Staff Accounting Bulletins, Topic 1.M., Materiality:6

Materiality concerns the significance of an item to users of a registrant's financial statements. A matter is "material" if there is a substantial likelihood that a reasonable person would consider it important. In its Concepts Statement 2, Qualitative Characteristics of Accounting Information, the FASB stated the essence of the concept of materiality as follows:

The omission or misstatement of an item in a financial report is material if, in the light of surrounding circumstances, the magnitude of the item is such that it is probable that the judgment of a reasonable person relying upon the report would have been changed or influenced by the inclusion or correction of the item...

Under the governing principles, an assessment of materiality requires that one views the facts in the context of the "surrounding circumstances," as the accounting literature puts it, or the "total mix" of information, in the words of the Supreme Court.

In fact, the SEC and the accounting profession have already established criteria that are consistent with the well-accepted premise that one consideration regarding whether an item is material is whether it could affect a reasonable person's judgment after considering the total mix of information. According to the Codification of Staff Accounting Bulletins Topic 1.M. , Materiality, "When, however, management or the independent auditor expects (based, for example, on a pattern of market performance) that a known misstatement may result in a significant positive or negative market reaction, that expected reaction should be taken into account when considering whether a misstatement is material."7 The phrase "expected reaction" is of particular importance.

Event Studies

A reasonable investor may or may not consider an accounting anomaly to be material upon disclosure. One way (though not the only way) to measure the economic impact of disclosing an accounting anomaly is through event studies, which are widely used in these circumstances.

An event study is a statistical technique that involves evaluating the potential materiality of a corrective disclosure based on a company's stock price movements. Assuming the market is efficient for a particular security, the presence or lack of an accompanying statistically significant price reaction (controlling for other factors such as market-wide influences, industry-wide changes and unrelated company-specific events) is often used as one indicia of materiality.

However, the AQM suggests that the SEC may scrutinize accounting anomalies that may not be accompanied by immediate and clear stock price movements.

The most obvious proxy for the "expected reaction" in this context is the company's actual stock price movement following the relevant announcement (market models and event studies are common tools used in this regard; see discussion above regarding Event Studies). To illustrate a simple example, if a company's stock price falls by 80% in response to the disclosure of a clear instance of financial reporting fraud, the SEC may well investigate. The SEC has and is likely to continue to use large stock price reactions as an input in selecting companies for further analysis. However, the advent of the AQM suggests that the SEC may become more proactive by identifying indicia and commencing investigations of potential financial reporting fraud prior to any corrective disclosures.

Consider the case of a company that the SEC suspects may have favorably misrepresented its financial statements in order to hide an adverse development. Such a misrepresentation could substantially enhance investor perceptions of the company vis-à-vis what they would otherwise have been, without boosting its stock price. Put another way, had this company reported its financial statements correctly, its stock price would have fallen rather than held steady. The AQM may well be applied by the SEC to investigate financial accounting anomalies that operate in this fashion. If the market for the stock is efficient, it should detect the same risk that the SEC did and incorporate that risk into the price. Even when it follows anomalous financial reporting, the announcement of an SEC investigation may cause a negative stock price reaction because it constitutes the realization of a previously disclosed risk; the market may also surmise that the SEC has detected non-public indicia of wrongdoing and/or that the costs of fixing the problem may be higher than previously expected. A subsequent SEC finding of a fraudulent accounting misrepresentation would likely cause an additional stock price movement (though that could even be an increase if it is determined that the actual accounting misrepresentation was less than the market had expected based on the initiation of the investigation). An SEC decision to drop the case with no action would likely cause an increase in the stock price.

The AQM, Stock Price Reactions and the Role of Market Efficiency:

One other possible use of the AQM would involve companies whose stock does not trade in an efficient market. In these cases, the SEC may decide to rely on fundamental valuation methodologies to evaluate the "expected reaction" of any given financial accounting anomaly.

It is also important to note that market efficiency is not a yes or no proposition. Taken to the extreme, a perfectly efficient market implies that a company could simply periodically deliver a shoebox of receipts and accounting records to investors to fulfill disclosure requirements, and the market would correctly process and interpret all the relevant data. Indeed, the purpose of establishing accounting standards is to provide periodic financial reports that are more effective than such a shoebox.

Consequently, we should consider the possibility that even for a company that trades in a reasonably efficient market, the AQM may facilitate the ability of the SEC to identify issues with substantial valuation consequences that may initially go unnoticed by the market at large.

Another situation could involve a company that the SEC suspects may have misrepresented its financial statements in a way that has a small or negligible impact in the current period, but that may build up to a large impact over time. Again, the SEC may well intend for the AQM to utilize methodologies that might detect issues that will build up over time.

ANTICIPATING SEC SCRUTINY

Companies Should Be Aware of Statistical Anomalies that the AQM Might Red-Flag

The new approach to detection of fraudulent or improper financial reporting has important implications for how reporting entities should anticipate heightened SEC scrutiny. Automated detection means that any statistical anomaly (regardless of whether it is a misrepresentation) might be identified and "red-flagged" by the SEC. This means that a company with financial metrics that are out of line with its past reporting or its peer group may be flagged by the SEC, even though there may be legitimate business explanations for the apparently anomalous financial results. For example, a company that attempts to expand its customer base by extending the period over which it permits customers to pay for credit purchases may nonetheless be flagged for unusually high earnings-to-cash flow ratios, even though the company is relatively sure of the collectability of its receivables and has established a reasonable allowance. Therefore, it is important for companies to preemptively evaluate whether their current-period financial data:

- Are out of line compared to their industry peers;

- Deviate from their own historical pattern; or

- Are internally inconsistent (such that their balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement do not fully reconcile with one another).

If one draws reasonable inferences from work done by economic consultants and insurers in trying to detect potential accounting fraud for public companies, then for certain accounting measures, the SEC is unlikely to set overly simplified criteria and thresholds to define financial reporting anomalies. Simply targeting companies with the highest revenue growth for a given reporting period is unlikely to be useful. Instead, the SEC is likely to establish a combination of criteria, which may collectively signal potential financial reporting errors or fraud. For example, the SEC might be more likely to investigate a company that reports high revenue growth:

- After years of consistently low/negative revenue growth;

- Concurrently with an industry-wide revenue slow-down or flat growth; and

- Unaccompanied by growth in cash receipts.

Analyses by economic consultants and insurers also suggest that other accounting measures, such as various financial ratios, may be likely to matter both in their absolute levels and based on how they have changed over time at a company. It is also likely that the SEC would not simply look at individual accounting measures in isolation, but would develop a model in which weights are assigned to anomalous measures across different accounting data so as to arrive at a summary indicator of potential accounting issues. Another important consideration would be the selection and application of accounting standards in the context of the industry or peer group.

Companies Should Be Aware of the Fundamental Valuation Consequences of Statistical Anomalies that the AQM Might Red-Flag

Ultimately, companies must also consider whether the SEC would likely find the valuation consequence of any financial reporting anomalies to be material. Ideally, companies would consider this when their operating activities result in apparently anomalous data in their financial statements. Such companies may attempt to preempt SEC scrutiny by addressing apparent accounting anomalies through adequate public disclosures. When correctly employed, fundamental valuation analysis can be a valuable tool in measuring the theoretical economic impact of any given financial accounting anomaly.

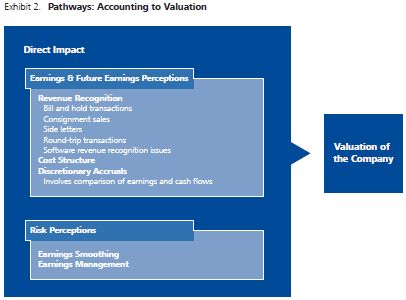

There are many pathways through which accounting anomalies would affect the valuation of a company, including a change in earnings, perception of future earnings growth, or a change in the perceived risk of the existing expected earnings stream (which could manifest itself as a change in the appropriate discount rate, for example). The following exhibit provides examples of how accounting issues could be associated with each of the pathways.8 Once a company identifies what the SEC may flag, it is important for it to make adequate disclosures to preemptively address this area of potential SEC – and investor – scrutiny.

Companies Should Make Adequate Disclosures to Preemptively Address Potential SEC Scrutiny

Companies that are flagged by the SEC may be able to explain in public filings any accounting anomaly as being due to a company-specific factor that improves its financial metrics relative to its prior performance or its peers. Such information can be furnished either with anticipatory public disclosures or in response to SEC inquiries (whether public or not). The company needs to demonstrate that factors such as changes in business prospects or competitive dynamics explain any statistical anomaly and that further investigation is not warranted.

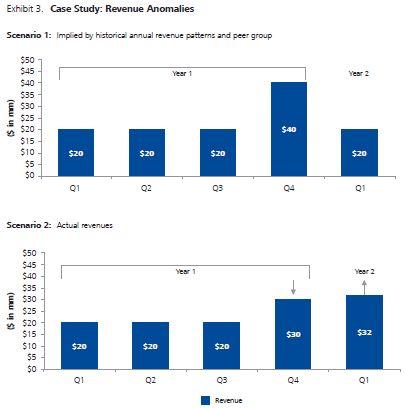

Case Study: Preemptive Disclosure of a Potential Revenue Recognition Anomaly

Assume that a company finds that its revenue in each of the last two quarters deviates from what would have been expected based on its historical pattern and that of its industry peers. Specifically, as illustrated in Exhibit 3 below, this company and its competitors have historically recognized a disproportionately large share of annual revenue in the 4th quarter. For the purposes of this illustrative example, assume that this pattern has persisted in the past. Its peers continue to exhibit this pattern, but the company reported revenues that were unusually low in its 4th quarter and unusually high in the following 1st quarter. In addition to the change in quarterly distribution of revenues, assume that the company has experienced flat annual revenues of $100 million over an extended number

of years, but has unexpectedly grown its annual revenues to $102 million in the most recent 12 months.

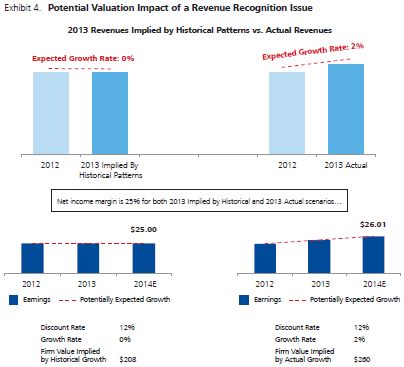

While this issue may have a reasonable business explanation, it is important for the company to be able to anticipate scrutiny and respond accordingly through preemptive disclosures. Indeed, the SEC might find reason to investigate this simply on the basis of the departure from historical quarterly revenue recognition patterns. This is not to say that a 2% growth in revenues from one year to the next by itself is vulnerable to automatic scrutiny. However, the combined impact of a change in quarterly revenue distributions, along with an unexpected small amount of revenue growth after years of stagnation, could increase the possibility of further attention. On the basis of these combined factors, the AQM might trigger a concern that this anomaly is related to an attempt to mislead the market into anticipating future revenue growth. Note that Exhibit 4 implies that historical patterns suggest revenues of $100 million over the four quarter period, while the actual revenues are $102 million. If the SEC does not believe that the disclosures surrounding the revenue growth are adequate, it may consider what the impact of a sustained 2% increase in expected revenue growth would be. As Exhibit 4 shows, the impact on firm value could be substantial under the extreme assumption that the company will continue to experience consistent 2% growth in the future.9

With the above in mind, the company's disclosure of a number of facts may be useful in avoiding further SEC scrutiny:

- The company might highlight its recent shift away from marketing timed to stimulate sales in the 4th quarter, a period of intense price competition, to marketing aimed at generating post-holiday sales.

- The company might further explain that the unexpected increase in revenues in the following 1st quarter is related to these increased marketing efforts, and may not be repeated in the future or may be repeated but without further growth.

While determining the proper threshold for what qualifies as an anomaly is a difficult task, it will be useful for companies to establish a system to define and detect potential accounting anomalies in anticipation of SEC scrutiny. Upon identification of a potential accounting anomaly, a company may want to increase its disclosure of details and circumstances surrounding it. Such disclosure may preempt a decision by the SEC to pursue further investigation of the company.

CONCLUSION

The SEC has telegraphed an enforcement strategy over the past year that has important implications for all public companies. Although the goal of the SEC has not changed, the availability of newer, more sophisticated enforcement tools has changed the landscape for companies. Companies, their outside accountants, corporate counsel, and others servicing the company's reporting needs and obligations should be aware of what may trigger scrutiny in order to anticipate it and be prepared to explain legitimate financial reporting anomalies that may appear suspicious. Indeed, to preempt SEC scrutiny, companies should demonstrate the application of acceptable accounting standards, anticipate potential market reactions and interpretations, and disclose the business reasons for potential financial reporting anomalies. A multi-disciplinary approach is advisable, given the broad areas of expertise required.

Footnotes

* The authors would like to acknowledge valuable input from fellow NERA colleagues John Garvey, Marcia Mayer, Jordan Milev, Robert Patton, and David Tabak, as well as Professors Mark DeFond at the University of Southern California, and Zoe-Vonna Palmrose at the University of Washington. The authors would also like to thank Joanne Jia, Steven Seidel, and Chris Shi for invaluable assistance in the drafting process and related research and analyses.

1 "Year-by-Year SEC Enforcement Statistics," http://www.sec.gov/news/newsroom/images/enfstats.pdf.

2 "Deploying the Full Enforcement Arsenal," Mary Jo White, Speech at Council of Institutional Investors fall conference in Chicago, IL, September 26, 2013.

3 "SEC Announces Enforcement Initiatives to Combat Financial Reporting and Microcap Fraud and Enhance Risk Analysis," SEC Press Release, July 2, 2013.

4 Often referred to in the popular press as the "Robocop" initiative.

5 "Q&A with an Expert: The SEC is Developing Tools That Use XBRL Data to Discover Accounting Anomalies and Improve Financial Disclosures," Merrill Corporation, April 9, 2013.

6 Securities and Exchange Commission, Codification of Staff Accounting Bulletins, Topic 1.M., Materiality.

7 Securities and Exchange Commission, Codification of Staff Accounting Bulletins, Topic 1.M., Materiality.

8 Note that certain issues (including regulatory capital requirements, credit ratings, etc.) may not have direct effects on earnings, cash flows, or risk perceptions, but may still affect the value of a company in more subtle ways.

9 This analysis employs a well-accepted valuation formula commonly known as the "Gordon Growth Model." This model estimates the value of a company as its expected dividends in the next period divided by the excess of its discount rate over its expected dividend growth rate. Here, we have simplified the application of the formula by assuming that earnings will be paid out as dividends. See, e.g., Damodaran, Aswath, Investment Valuation, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY, 2002.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.