Originally published in the January/February 2008 issue of Corporate Board Member

Corporate Board Member, in association with Katten Muchin Rosenman LLP, recently surveyed corporate directors to better understand their views on issues related to shareholder litigation. Inside this special section, we present the full results of this research, along with rock solid advice on how to avoid shareholder suits and what to do if your board finds itself in the middle of such action.

Corporate Board Member, in association with Katten Muchin Rosenman LLP, recently polled 1,344 directors on their opinions regarding the current state of securities class-action suits and the board's role in managing such litigation. Afterward, we sat down to discuss the results and glean additional insights from Bruce G. Vanyo, cochair of Katten's Securities Litigation practice, and David H. Kistenbroker, its Chicago office managing partner, chairman of the National Litigation Department, and cochair of the firm's Securities Litigation practice.

What is the current environment for shareholder class-action suits?

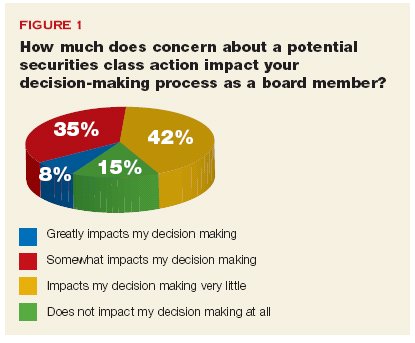

Bruce G. Vanyo: We are in the midst of a very interesting period for shareholder class-action lawsuits. While some directors are fairly concerned about the current environment, others seem somewhat complacent about it (Figure 1). Setting aside the options backdating suits related to conduct that disappeared years ago, we have had two straight years where the number of lawsuits has been well below historical levels. This is good news for companies and their directors. Yet, nobody really knows whether this is a long-term decline or whether it is a temporary drop. There are many theories as to the reason for this decline, including the stock market's recent stability, more thorough oversight of management that resulted after Sarbanes-Oxley, less instances of fraud, and the criminal investigations of the two largest securities class-action plaintiff firms. But in reality, these theories do not tell us whether we are likely to continue to see fewer lawsuits in the future.

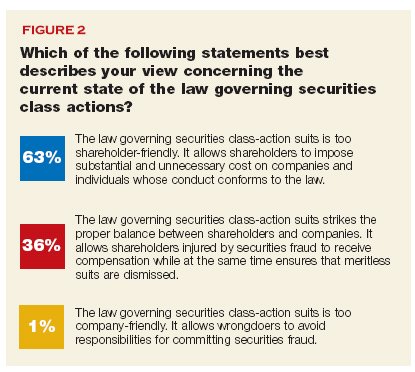

The other bit of good news for boards is that despite the fact that a majority of those polled feel the pendulum is swinging more toward shareholders' rights at present (Figure 2), the Supreme Court has issued a couple of securities class-action opinions in the last few years that are, relatively speaking, company-friendly. These opinions, and some of the other case law that has developed throughout the country since Congress passed the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act in 1995 (PSLRA), might make plaintiffs think twice before immediately suing a company just because its stock price fell. This line of thinking, however, tends to be cyclical. Congress responded to the frequent filing of class-action lawsuits by passing the PSLRA to make it harder to bring this kind of litigation. After the Enron and WorldCom scandals, Congress reacted by passing the Sarbanes-Oxley Act to increase oversight, and courts responded with greater skepticism toward companies' claims that no fraud exists. And now we find ourselves tilted the other way again.

David H. Kistenbroker: While there is some good news, there is bad news, too. The shareholder suits that are brought today tend to be better researched by the plaintiffs. With increasing frequency, plaintiffs seem to be spending more time looking for former company employees to provide them information. These former employees usually are labeled as confidential witnesses in the complaints and, seemingly are persons who are not particularly friendly toward their former employers. Also, in more and more cases, plaintiffs' lawsuits coincide with SEC investigations and DOJ investigations that are of greater concern to the company. These government investigations come with their own set of problems and they also make it much more difficult to prevail in private litigation because the government investigations and the company's disclosures concerning these investigations give plaintiffs' lawyers a road map to follow in pursuing their own lawsuits.

We also see an increasing trend where companies, sometimes at their own initiative but often at the behest of their auditors, are conducting internal investigations to determine if anyone associated with the company has done anything wrong. These internal investigations can become very expensive, take a long time, and have both short- and long-term effects on a company's stock price.

Internal investigations can also result in an adversarial relationship between the board and company management that is not always in the best interests of the shareholders and the company's growth. Boards must exercise healthy skepticism in order to perform their oversight role in the best way, but when skepticism becomes mistrust, sometimes without justification, productivity declines.

The joint research between Corporate Board Member and Katten shows that legal liability related to accounting irregularities seems to give directors the most concern. What types of suits should boards be most concerned about today?

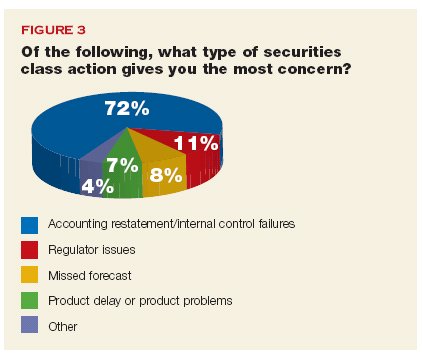

Kistenbroker: Overall, I think directors have this one right (Figure 3), and are correct to place less emphasis on missed forecasts, product delays, and regulatory compliance issues. It really is hard to say what kind of securities class-action lawsuit is most prevalent, but it is the accounting restatement cases where the atmosphere for the perfect storm is most likely to develop.

Vanyo: That perfect storm is what David was describing before. Auditors will often insist that the company conduct an internal investigation to determine if an isolated accounting error is a sign of something larger. The SEC then opens an investigation because a restatement requires an amendment to past SEC filings. The DOJ might also get involved. Finally, plaintiffs bring a securities class action. This results in the company and its directors feeling like they are being attacked on all sides.

Kistenbroker: The other kind of case that we think is problematic–though we don't see it as frequently–is the forecast miss or product delay shortly after an IPO. We have seen an increase in the number of these cases lately, and they are more difficult to resolve because plaintiffs get the benefit of statutes that do not require them to show intent to deceive. Shareholders–and courts–are also skeptical when a company has problems right after it has gone public, as they do not always understand that these newer companies generally have more volatility and less visibility into their future.

If a board finds itself on the receiving end of a shareholder class-action suit, what are the immediate steps it should take?

Vanyo: First, the board needs to quickly obtain an understanding of the issues that have resulted in the class-action suit. It should hire counsel with significant experience in defending class actions. Along with that, the company should make sure it puts its insurance carriers on notice of the suit. Another important step is for the company to ensure its ordinary document retention policy is suspended so that documents related to the lawsuit are not accidentally destroyed. Counsel should undertake a focused collection of the most significant documents related to the lawsuit and should conduct interviews of the most important witnesses. This initial investigation helps everybody to understand if there really is a problem and, if so, the scope of the problem.

The issues that result in class-action suits usually stem from a specific area of the company's business so that, generally, there is no need to conduct an overarching analysis of the entire company, or even to have an overall knowledge of all aspects of the company. This is the scalpel approach as opposed to the machete approach, and the overall goal is to conduct a risk analysis and develop a defense strategy in an efficient manner. Doing so does not need to interfere with ordinary business operations or get in the way of company progress.

Kistenbroker: We have found that the biggest mistakes a company and its board make in the early stages are (1) to assume that there is no problem and conduct business as usual without initiating an early inquiry or (2) to react too quickly by immediately retaining litigation counsel from the same firm as its corporate counsel and then conducting a full-scale analysis of the entire business, an approach that is very disruptive to the company as a whole. There obviously is a continuum of approaches that range between doing nothing and turning the business upside down. Experienced counsel can help make judgments about where on the continuum the case belongs. This cannot be done, however, without the initial exploratory and efficient preliminary analysis.

Can you discuss the various potential outcomes of a shareholder suit a board might need to prepare for?

Vanyo: Our goal going into every shareholder class action is to have a successful motion to dismiss before there is any discovery, and each time, we put substantial efforts into making that happen. When it does not, we focus next on defeating plaintiff's effort to have a class certified, which, depending on the type of case and allegations, can defeat the entire case. Lately, courts have been more willing to scrutinize motions for class certification, which provides companies with another avenue of argument. After class certification, the alternatives are essentially victory on summary judgment, victory by completely undermining plaintiff's theory of damages as part of motions to exclude plaintiff's damages experts, or victory after trial.

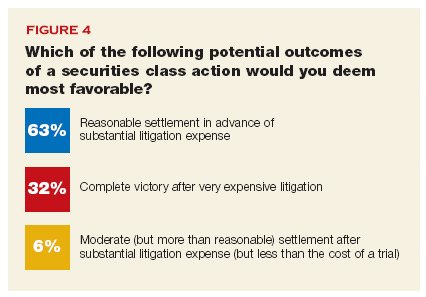

Kistenbroker: However, it's important to note that there are very few securities class-action cases that get tried. We had one a number of years ago that we won, but generally, defendants either win the case pretrial or the case settles. It is not surprising that our study found most directors prefer reasonable settlements over complete victory after trial (Figure 4). Directors are trained to make risk/reward judgments and a trial can be a high-risk proposition where the downside can be very large.

Having said that, as litigators, we always have to be ready to go to trial and must prepare our cases as if every one is going to trial. But at the same time, our clients must consider the broader implications of going to trial–not just in terms of a possible large damage award but also in terms of the distraction of company executives, media coverage, and other business considerations. I was actually more surprised at the percentages for the survey numbers that refer to a settlement for more than reasonable amounts and complete victory after trial, as these numbers really seem to indicate how unwilling companies are to go to trial.

Vanyo: We frequently wonder whether it makes sense to take more of these cases to trial. From our standpoint, we believe most companies are not engaging in any intentional wrongdoing, and we believe that judges and even juries would see that. But it is harder to second-guess a settlement–even one that is more than reasonable– than it is a loss, after trial.

Prevention: The Best Medicine

What is your advice for boards that want to prevent a shareholder class action from ever being filed?

Kistenbroke It is very hard to outline any recipe that, if followed, will prevent plaintiffs from bringing a shareholder lawsuit. That said, I think one of the key items is to make sure management keeps the board updated concerning all aspects of the company's business. For their part, the directors should exercise healthy skepticism concerning what they are told and should ask tough questions without being unnecessarily contrarian. Boards should also try not to let their companies get caught up in meeting or exceeding Wall Street's numbers. There also is a tendency to put many more resources into growth than into managing that growth. Obviously, companies should focus on increasing revenue and earnings and other similar metrics, but oftentimes, companies forget to increase the necessary infrastructure to make sure that growth is properly managed. We understand that companies want to increase the number of employees doing R&D or marketing or sales and decrease the number of accounting personnel, but this can be very detrimental to the business in the long run.

Vanyo: The other thing directors can do is make sure they have adequate protection in the event a shareholder lawsuit is filed. Doing so means scrutinizing indemnification agreements to ensure they provide appropriate protection and purchasing the right amount of insurance, based not just on the cost of the insurance but also on the terms and scope of coverage. Directors and officers liability insurance policies are negotiable, and companies can often obtain better terms than those included on the standard forms.

Kistenbroker: Boards should also consider receiving reports not just from the CEO, COO, and CFO, but also from other members of management. We realize that board packets continue to grow thicker and thicker and board meetings are lasting longer and longer, but one practice we think is worth consideration is for the board to receive a detailed report concerning one specific department at each meeting, with each department rotating who makes the presentation at each meeting. This can be structured either by focusing on areas of greatest risk or some other metric that makes sense for the company.

Vanyo: An area that warrants more attention is revenue recognition. We previously mentioned that cases that have their genesis in an accounting restatement are the most difficult to defend. These cases often arise because of problems relating to improper revenue recognition. Frequently, this is because the sales force engages in practices about which the finance and accounting personnel are not aware. While these sales practices are driving sales in a general sense, they might not comply with the accounting rules related to revenue recognition. This is an area in which the board of directors can increase its focus and thereby decrease the likelihood of a future shareholder lawsuit. The board can make sure the sales team is educated by the accounting personnel about the necessary preconditions for revenue recognition to eliminate any possible conflict. It can also make sure that there is better communication between sales and accounting concerning sales practices so that accounting personnel know what the sales personnel are doing.

Kistenbroker: Similarly, if a company has particular issues with respect to its forecasting process, having the board request a report on this topic–and the resulting increased scrutiny–might lead to improvements in forecasting accuracy.

It also makes sense for the board to work with management and counsel to draft corporate risk disclosures for SEC filings and other public documents that are specifically tailored to the risks facing the company. These documents should have sufficient specificity to avoid being challenged as simply boilerplate. Courts are increasingly skeptical of a company's risk disclosures as failing to be sufficiently specific or tailored to the company's actual issues. As a result, many courts have been unwilling to apply the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act's safe harbor provision for forward-looking statements early on in cases, which would help dismiss lawsuits based on risks about which the company previously has provided warning. While the PSLRA's safe harbor provision does not get as much focus at the pleading stage as the standards for pleading falsity and scienter, it is still a powerful defense tool under certain circumstances. We believe that more focus on the risk disclosures in the prelitigation stages can have real benefits when something does go wrong, either in making plaintiffs less willing to initiate what will ultimately be a losing lawsuit or in helping achieve an early victory prior to discovery. As we mentioned before, this is always our first goal with respect to any securities class action.

Vanyo: Companies are always going to run into problems, and shareholders will always sue if these problems cause a company's stock price to fall. The key is to manage those lawsuits to make sure that they do not disrupt the company's business operations, remain contained, and are successfully resolved as early as possible.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.