A stipulated judgment of patent non-infringement based on claim construction may sound straightforward as an appellate matter. The appeal should turn on claim construction — often a clean issue of law. But when the stipulation is ambiguous, even a seemingly focused dispute like this can unravel. The Federal Circuit's precedential decision in AlterWAN, Inc. v. Amazon.com, Inc., No. 2022-1349 (Fed. Cir. Mar. 13, 2023), illustrates the dangers of nonspecific stipulated judgments.

In AlterWAN, Amazon was accused of infringing two patents directed to accelerating traffic in wide area networks. The patents described providing a "private tunnel" that offered "preplanned high bandwidth, low hop-count routing paths between pairs of customer sites." This would purportedly reduce latency as packets hopped between locations en route to destinations.

In claim construction and summary judgment briefing, the parties disputed the meaning of two key claim terms: (1) "non-blocking bandwidth" and (2) "cooperating service provider." The district court construed "non-blocking bandwidth" to mean "bandwidth that will always be available and will always be sufficient," regardless of whether the internet was operating or not, as Amazon proposed.

After two rounds of briefing, the district court construed "cooperating service provider" to mean "service provider that agrees to provide non-blocking bandwidth," which was again Amazon's proposal. Based on these two constructions, the parties stipulated to summary judgment of non-infringement.

More precisely, they stipulated as follows: "Under the Court's constructions of 'cooperating service provider' and 'non-blocking bandwidth,' Amazon has not infringed, and does not infringe, the '478 and '471 patents."

This is where problems arose. The construction of "cooperating service provider" incorporated the term "non-blocking bandwidth," which was itself a construed term. There were thus two distinct claim construction disputes, one partially nested in the other.

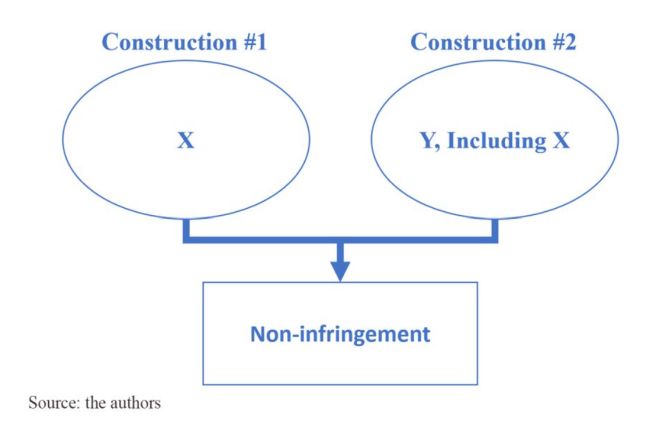

The parties' stipulation of non-infringement did not address whether both constructions, or only one, were necessary for non-infringement. The stipulation also did not identify particular claims underlying the judgment, which was further complicated by the fact that some claims used "cooperating service provider" while other claims used "non-blocking bandwidth." The stipulation may broadly be conceptualized as follows:

AlterWAN's appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit challenged both claim constructions. The Federal Circuit was unable to reach the merits, however, because of the ambiguities in the parties' stipulation. Specifically, the Federal Circuit found it "unclear whether the judgment requires the affirmance of both 'cooperating service provider' and 'non-blocking bandwidth,' where the interpretation of cooperating service provider includes the term 'non-blocking bandwidth.'" In addition, it was unclear "whether affirmance requires the approval of all aspects of the construction of 'cooperating service provider.'"

Adding to this facial ambiguity in the stipulation, oral argument in the appeal confirmed that the parties had substantially different understandings of its meaning. AlterWAN argued that the sole basis for non-infringement was the portion of the construction for "non-blocking bandwidth" requiring that bandwidth always be available regardless of whether the internet was operating. According to AlterWAN, it was impossible to provide bandwidth if the internet was down and thus no network, including Amazon's, could infringe under that construction.

By contrast, Amazon argued that other portions of the claim constructions supported the judgment of non-infringement. Amazon contended that there was no infringement under the construction of "cooperating service provider," regardless of whether the limitation concerning internet availability was included in the construction.

The Federal Circuit vacated the parties' stipulated judgment as ambiguous. As the Federal Circuit explained, "stipulating to non-infringement based on a district court's claim constructions without indicating the exact basis for non-infringement" may preclude appellate review. Because the stipulation here did not identify the specific claims at issue and did not "provide any factual context as to 'how the disputed claim construction rulings relate to the accused products,'" the specific basis for judgment was unclear and thus not amenable for appeal.

While the Federal Circuit did provide some additional guidance on the meaning of "non-blocking bandwidth" — that it cannot cover the impossibility of providing bandwidth when the internet was down — the Federal Circuit vacated the stipulated judgment and remanded. On remand, the district court will "determine whether a stipulation of non-infringement is even possible in the circumstances of this case."

The Federal Circuit's opinion in AlterWAN provides important guidance for parties entering stipulated judgments. As a threshold matter, parties should carefully assess what issues remain in dispute before entering a stipulation. As the opinion shows, parties may have different understandings of disputed issues. Once a dispute's contours are known, parties should take care in crafting a stipulation.

The stipulation should identify the patent claims at issue. It should also make clear to the Federal Circuit what issues — claim construction or otherwise — are necessary to the judgment. And it must do so with specificity, to "adequately explain how the claim construction rulings relate[] to the accused systems." Without such clarity and specificity, the Federal Circuit may be left to guess about the impact its rulings may have, and thus may be unable to hear the merits of the appeal.

Originally Published by Reuters

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.