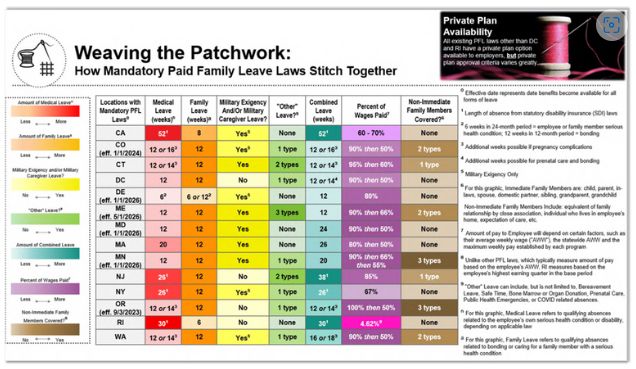

Seyfarth Synopsis: With each passing year, the country's patchwork of mandatory state paid family and paid family medical leave (collectively, "PFML" or "PFL") laws continues to evolve and expand. Why is this existing patchwork so challenging for employers? Look no further than how varied these laws are in terms of their substantive and procedural components. The below graphic illustrates this complexity by highlighting four key PFML substantive areas – (1) qualifying absences, (2) covered family members, (3) length of benefits and duration of leave, and (4) amount of pay.1

(click or tap graphic to enlarge resolution)

American companies provide generous paid leave benefits to millions of employees to help balance work and personal health, caregiving and parental responsibilities. Meanwhile, 13 states, plus Washington, D.C., have enacted a patchwork of inconsistent mandatory paid family and paid family medical leave (collectively, "PFML" or "PFL") programs, each with differing substantive and procedural requirements. Importantly, not only is there a current patchwork of inconsistent mandatory PFML programs around the country that are challenging to navigate given their many variations, but the patchwork continues to grow as these laws evolve and expand into new locations.

For instance, since the start of 2022, four states have enacted new mandatory PFML programs – Maryland and Delaware in 2022, and Minnesota and Maine in 2023. Several other states – nonexclusively, Colorado, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Oregon, and Washington – plus Washington, D.C., have updated their respective PFML programs through formal amendments, additional rulemaking, or issuing administrative guidance. 2024 appears poised to continue this trend with PFML legislative activity occurring in various states, including but not limited to, Virginia, Hawaii, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. Further adding to the complexity is that other states are enacting voluntary PFML programs or adding paid family leave as a class of insurance. Navigating this patchwork has become a significant burden for multistate and nationwide employers, as well as led to hardships and inequities for their employees.

Why is the existing patchwork of mandatory state PFML programs so challenging? The answer starts with how varied these laws are in terms of their substantive and procedural components. Mandatory PFML programs are comprised of more than 30 substantive, technical requirements, many of which have additional layers, such as definitions, formulas, and administrative standards. When examined, it is clear that many of these measures are mismatched and misaligned.

Deviations across four select key PFML substantive areas – (1) qualifying absences, (2) covered family members, (3) length of benefits and duration of leave, and (4) amount of pay – are reflected in the graphic above.2 As highlighted, wide variations and nuances exist across each topic.

With the paid leave landscape continuing to rapidly expand and grow in complexity, we encourage companies to reach out to their Seyfarth contact for solutions and recommendations for addressing compliance with paid leave requirements.

Footnotes

1 This infographic was prepared by Seyfarth's Leaves of Absence Management and Accommodations team in conjunction with the American Benefits Council.

2 Notably, these four topics account for only a small portion of PFML law substantive criteria. Examples of other mandatory PFML conditions include: (5) employee eligibility, (6) employer coverage, (7) treatment of remote, hybrid and mobile workers, (8) benefit year calculation, (9) key definitions, such as "parent," "child," "serious health condition," etc., (10) job protection, (11) funding, (12) waiting periods, (13) intermittent leave, (14) employee notice and scheduling, (15) documentation, (16) medical recertification, (17) interplay with employer-provided leave and time off, (18) interplay with other laws, (19) notice to employees, including new hires, (20) posting, (21) claim filing processes, (22) benefits continuation, (23) employee disqualification, (24) confidentiality, (25) recordkeeping, (26) anti-retaliation, discrimination and interference, (27) reporting and remitting, (28) treatment of union workers, (29) treatment of self-employed workers, (30) written policy requirements, and (31) private plans.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.