1 Legal framework

1.1 Which laws and regulations govern patent litigation in your jurisdiction?

Patents in the United States are governed by the Patent Act Title 35, which established the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure generally govern the procedures related to patent litigations in the United States. Each federal district court may also have its own local rules governing actions before the court. With respect to evidentiary rules, the Federal Rules of Evidence govern the admission and use of evidence. For post-grant patentability challenges conducted at the USPTO, the America Invents Act established the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). The PTAB is a tribunal that hears and adjudicates challenges of issued patents in post-grant reviews and inter partes reviews. The PTAB has its own set of rules and regulations that govern the proceedings in that venue.

1.2 Which bilateral and multilateral agreements with relevance to patent litigation have effect in your jurisdiction?

There are numerous bilateral and multilateral agreements that are relevant to US patents and patent litigation. For example, the United States is subject to the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, which includes standards for IP protection with mechanisms for enforcement and dispute resolution. Also, the Patent Cooperation Treaty and the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property are relevant to priority claims and procedures for filing patent applications in multiple jurisdictions, including the United States. Additionally, the Hague Convention on the Taking of Evidence Abroad in Civil or Commercial Matters is relevant to requests for seeking discovery from foreign jurisdictions. This multilateral treaty outlines the mechanisms by which judicial authorities in one country can obtain evidence in another country. There is also the Hague Convention on the Service Abroad of Judicial and Extrajudicial Documents in Civil or Commercial Matters, which provides a framework for serving documents on parties located in another country.

1.3 Which courts and/or agencies are responsible for interpreting and enforcing the patent laws? What is the framework for doing so?

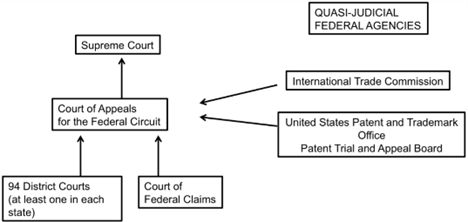

The following diagram provides an overview of the courts and agencies in the United States that are responsible for handling disputes and proceedings related to patents.

The United States follows the common law tradition of applying caselaw precedent. For patent disputes, this means that the federal district courts, the Court of Federal Claims and the International Trade Commission are bound by decisions of appellate courts, primarily the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. They also generally follow prior decisions within their own jurisdiction. Decisions from other domestic jurisdictions (eg, federal district courts in other states or circuits) have persuasive authority but are not mandatory precedent. Exceptions include doctrines such as collateral estoppel and res judicata. These doctrines may bind the parties to findings of law and/or fact in one jurisdiction to the same findings if the parties try to relitigate the issues in the same or another jurisdiction. The interplay between district court litigations and PTAB rulings is also important. In general, courts are not required to adhere to a PTAB ruling that a patent is unpatentable unless and until the PTAB ruling is final and all appeal rights have been exhausted.

2 Forum

2.1 In what forum(s) is patent litigation heard in your jurisdiction? Are patent infringement and validity decided in the same forum or separate forums?

In the United States, a patent lawsuit may be initiated in a federal district court. There are 94 federal district courts in the United States. A single judge will preside over a patent case, which often includes issues related to infringement and validity. With the exception of abbreviated new drug application (ANDA) litigations a party may request a trial by jury. The time from filing a patent lawsuit to a first-instance decision following a trial varies across US district courts. On average, it can take three to four years from the filing of a complaint to a decision on the merits.

In terms of other first instance forums, the Court of Federal Claims hears patent infringement actions against the federal government. Also, the International Trade Commission (ITC) is an administrative agency through which a complainant may request an order to block the importation of infringing products. In addition to establishing the infringement by the imported products, the complainant must demonstrate that there is a 'domestic industry' related to the patented technology that exists or is in the process of being established in the United States.

Separately, the patentability of an issued patent may be challenged in a post-grant review and inter partes review before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) of the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). The PTAB also handles appeals of patent application rejections and derivation proceedings.

2.2 Who hears and decides patent disputes (eg, a judge, a panel and/or a jury)?

In a federal district court, a single judge typically presides over the litigation and issue orders on motions and claim construction, as well as other disputed issues. With the exception of ANDA litigation, the trial is often conducted before a jury. The members of the jury are selected laypersons (ie, members of the public), who are tasked with weighing the evidence and deciding issues relating to infringement and validity. At the PTAB, a panel of three administrative patent judges (APJs) oversee the proceedings and issue a final written decision on the patentability of the challenged claims of an issued patent. APJs have significant experience in patent law and have at least a bachelor of science degree in an engineering or scientific discipline and a law degree. Litigation at the ITC is conducted before a single administrative law judge (ALJ). The ALJ will issue an initial determination following the evidentiary hearing. The parties may petition the ITC to review all or part of the initial determination. Following additional briefing, if granted, the ITC will issue a final determination and, if applicable, exclusion and/or cease and desist orders.

2.3 Are there any opportunities for forum shopping in your jurisdiction? If so, where and how do those opportunities exist?

Subject to personal jurisdiction and venue requirements, a patent lawsuit in the United States can often be filed in one of several possible jurisdictions. As a result, deciding where to file is a key consideration when developing a litigation strategy. The factors that guide where to file a litigation in a federal district court – either as a patent owner-plaintiff or as a declaratory judgment-plaintiff – include:

- the time to trial;

- the win rate;

- the history of damages awards and/or other remedies; and

- the likelihood of a stay pending a PTAB proceeding related to the asserted patent(s).

In addition, parties often consider other factors such as local demographics and whether they have a business presence in the jurisdiction, which may be helpful for a case tried by a jury.

3 Parties

3.1 Who has standing to file suit for patent infringement? What requirements and restrictions apply in this regard?

Two categories of rights holders may file a patent suit:

- the patent owner; and

- an exclusive licensee with all substantial rights under the patent.

A patent owner is an entity owning all rights and title in a patent. An exclusive licensee is generally an entity that, while not receiving legal ownership of a patent, receives all substantial rights (eg, the rights to enforce and collect damages). By contrast, a bare licensee (ie, an entity that merely holds the right to practise a patent) has no standing to bring a lawsuit to enforce a patent. In addition, a patent owner may restrict the rights of an exclusive licensee, precluding its ability to sue independently or requiring the joinder of the patent owner to the action.

3.2 Can a patent infringement suit be brought against a defendant who is a foreign entity with only a residence or place of business outside the jurisdiction?

Venue in patent infringement cases is appropriate in the judicial district where:

- "the defendant resides"; or

- "the defendant has committed acts of infringement and has a regular and established place of business".

For foreign defendants with no place of business in the United States, venue is generally appropriate wherever the defendant is subject to personal jurisdiction.

3.3 Can a single infringement action be brought against multiple defendants? What requirements and restrictions apply in this regard?

A plaintiff can join defendants in a single action if the claims arise from common questions of facts or law. For example, if a retailer sells a product that infringes on a patent, the patent owner or exclusive licensee can join both the retailer and the retailer's supplier for infringement. Also, the manufacturer of the product can be joined as a co-defendant.

3.4 Can a third party seek a declaration of non-infringement or invalidity in your jurisdiction? If so, how?

A third party, such as an alleged infringer, can seek a declaratory judgment of non-infringement or invalidity in a federal district court. To file such an action the third party must demonstrate that:

- a substantial controversy exists between it and the patent owner; and

- the controversy has sufficient immediacy and reality to warrant the issuance of a declaratory judgment.

Without this, the court may dismiss the case for lack of declaratory judgment jurisdiction and lack of subject-matter jurisdiction. To challenge the patentability of a patent, any entity (other than the patent owner) may petition for a post-grant review (PGR) or inter partes review (IPR) before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board. However, there are some restrictions. For example, a third party that files a civil action in court to request a declaratory judgment of invalidity cannot then file a petition for a PGR or IPR.

4 Patent infringement

4.1 What constitutes patent infringement in your jurisdiction?

Generally, there are two types of infringement:

- Direct infringement: This occurs when a party performs or provides all of the actions needed to establish infringement of a patent claim. Those acts can include:

-

- making, using, offering for sale or selling the invention protected by the patent in the United States; or

- importing the invention protected by the patent into the United States.

- Direct infringement may also be committed by more than one party, but only when one party directs or controls another's performance, such as when there is a principal-agent relationship, contractual arrangement or joint enterprise.

- Indirect infringement: This may take the form of either inducement to infringe or contributory infringement. A party may be liable for inducing infringement if it knowingly induces another to directly infringe a patent – for example, by providing instructions on how to use a product which, when performed, will infringe the patent can be a basis for inducement. A party may be liable for contributory infringement if it provides a component or material especially made or adapted to be used in an infringing manner. For example, if a party provides a part that is not infringing by itself but is especially made to be combined with a different part to form an infringing device, this can provide a basis for contributory infringement. For both inducement and contributory infringement, an underlying instance of direct infringement must be shown.

4.2 How is infringement determined?

Infringement occurs when an accused product or method falls within the scope of a claim of the patent. Each element of the claim must be present literally or under the doctrine of equivalents. Claim construction is determined by the court – usually through a process where the parties submit briefing on disputed claim terms and then present their proposed constructions for the disputed terms at a hearing before the court known as a 'Markman hearing'. Where there is no literal infringement, infringement can still be found under the doctrine of equivalents. According to this doctrine, infringement occurs if a product or method does not fall within the literal scope of the construed claim but is the substantial equivalent of the patented invention. To determine equivalence, a judge or jury analyses whether the differences between the two are insubstantial to one of ordinary skill in the art. Prior art and prosecution history estoppel can limit or block the application of the doctrine of equivalents.

4.3 Does your jurisdiction apply the doctrine of equivalents?

In the United States, courts have recognised and found infringement under the doctrine of equivalents. According to this doctrine, infringement occurs if a product or method does not fall within the literal scope of the properly construed claim but is the substantial equivalent of the patented invention. To determine whether an element in the alleged infringer's product is equivalent to a claimed element, a judge or jury analyses whether the differences between the two are insubstantial to one of ordinary skill in the art. One common way to approach this inquiry is the function-way-result test, which assesses whether an element in an accused product or process performs substantially the same function, in substantially the same way, to accomplish substantially the same result as the claimed element.

4.4 Is wilful infringement recognised? If so, what is the applicable standard?

A prevailing patent owner in the United States is entitled to monetary damages. Generally, there are two forms of damages: compensatory damages and enhanced damages. Compensatory damages may be computed on the basis of a reasonable royalty or lost profits. When wilful infringement is established, the court may enhance the damages up to three times the amount found or assessed (so-called 'treble damages'). Under the current standard for wilful infringement, enhanced damages are available if the infringer engaged in egregiously infringing behaviour. This requires that the infringer:

- knew of the patent;

- knew of the infringement; and

- affirmatively decided to proceed with the infringing conduct.

5 Bringing a claim

5.1 What measures can a patent holder take to enforce its rights in your jurisdiction? Are interim measures available before receiving a ruling on the merits?

A patent owner may request a preliminary injunction or a temporary restraining order as an interim measure. However, interim measures are regarded as an extraordinary remedy and require that the patent owner demonstrate, among other things:

- a substantial likelihood of success on the merits; and

- the prospect of irreparable harm absent the injunction.

Alternatively, as an interim measure before trial, a patent owner (as well as the accused infringer) may move for a summary judgment ruling in a patent case. Summary judgment involves an adjudication by the court on one or more issues where there is no genuine question of material fact requiring a trial on the issue(s). Summary judgment motions can address dispositive issues, such as infringement or validity; although partially dispositive motions are possible as well (eg, addressing one or more accused products or asserted claims).

5.2 What is the limitation period for patent infringement in your jurisdiction?

Under 35 USC Section 286, a patent owner is not permitted to recover damages based on infringement occurring more than six years before the suit is filed. In some cases, certain defences may bar a party from bringing a patent suit, such as laches or estoppel.

5.3 Must the alleged infringer be notified in advance before a claim is brought?

If a patent owner has made or licensed products under an asserted patent, notice is required to recover pre-suit damages. In such cases, the patent owner must prove that:

- it provided the public with constructive notice of its patent rights by marking its patented products with the patent number; or

- the alleged infringer was notified of the infringement (ie, the patent owner provided actual notice) and continued to infringe thereafter(38 USC Section 287(a)).

With respect to actual notice, it requires an affirmative communication of a specific charge of infringement by a specific accused product or device, regardless of how the alleged infringer may have interpreted a communication about potential infringement.

5.4 What are the procedural and substantive requirements for bringing a claim for patent infringement? How much detail must be presented in the complaint?

To file a patent infringement lawsuit, a patent owner must conduct a reasonable and good-faith pre-suit investigation into the facts and law underlying their claims. Failure to conduct a proper pre-suit investigation may result in sanctions and dismissal of the action. In terms of the level of detail required for a complaint, the complaint must contain more than threadbare recitals of the elements of the cause of action and conclusory statements. Instead, the complaint must have sufficient detail to put the defendant on notice of what activity is being accused of infringement. The required level of detail will be driven by factors such as:

- the complexity of the technology;

- the materiality of the element to practising the asserted claims; and

- the nature of the allegedly infringing device.

5.5 Are interim remedies available in patent litigation in your jurisdiction? If so, how are they obtained and what form do they take?

A patent owner may request a preliminary injunction or a temporary restraining order as an interim measure. Such interim measures are regarded as an extraordinary remedy in a patent suit. To obtain a preliminary injunction, the patent owner must demonstrate:

- a substantial likelihood of success on the merits;

- the prospect of irreparable harm absent an injunction; and

- that:

-

- the balance of harms from an injunction supports granting the injunction;

- monetary damages would be inadequate; and

- the public interest favours grant of the injunction.

The best case for a preliminary injunction typically involves a competitor-competitor dispute, where one party is alleged to have committed infringement through copying the other party's patented products. However, even if all factors are satisfied, the court still has discretion as to whether to grant a preliminary injunction. With respect to a temporary restraining order, these are short-term pre-trial preliminary injunctions. As with a preliminary injunction, the patent owner must show special circumstances for the order, including an immediate irreparable injury unless the order is issued. If the judge is convinced that a temporary restraining order is necessary, the order may be issued immediately without informing the defendant or holding a hearing.

5.6 Under what circumstances must security for costs and/or damages incurred by the other party be provided?

If a preliminary injunction or temporary restraining order is granted (both of which are deemed extraordinary measures and not frequently granted in patent cases in the United States), the court may require that the patent owner post a bond covering the economic harm that would befall the accused infringer if the injunction were later found to be erroneous.

6 Disclosure and privilege

6.1 What rules on disclosure apply in your jurisdiction? Do any exceptions apply?

At the onset of a patent litigation, all parties are required to make initial disclosures. Such disclosures must be made without waiting for discovery requests from the other party and require the disclosure of information such as:

- the name and address of each individual likely to have discoverable information; and

- a copy – or a description by category and location – of all documents that the disclosing party has in its possession to support its claims or defences.

Following the exchange of initial disclosures, parties are generally entitled to discovery of documents and information regarding any nonprivileged matter that is relevant to any party's claim or defence. Discovery requests – including requests for documents, requests for admissions, requests to inspect property or other items and interrogatories – will be issued by the parties to gather such documents and information. Also, before trial, fact and expert witnesses will be deposed to gather their testimony.

6.2 What rules on third-party disclosure apply in your jurisdiction? Do any exceptions apply?

Parties may serve subpoenas on third parties, requiring:

- the production of documents;

- the inspection of premises; and/or

- witness testimony.

For a litigation or proceeding in a foreign or international tribunal, a US district court may order a US resident to give testimony or produce documents for use in that litigation or proceeding. The district court will consider factors such as the nature of the proceedings and the laws of the foreign jurisdiction before deciding whether to issue the order.

6.3 What rules on privilege apply in your jurisdiction? Do any exceptions apply?

Attorney-client privilege shields from discovery legal advice given to a party by its attorney and communications from the party (the client) to the attorney. There are some exceptions to this privilege. For example, the voluntary disclosure of privileged information to a third party will result in the waiver of attorney-client privilege. The scope of the waiver can extend beyond the document initially produced so that a party is prevented from disclosing communications that support its position while simultaneously concealing communications that do not. To determine the scope of the subject matter waived, courts will weigh:

- the circumstances of the disclosure;

- the nature of the legal advice sought; and

- the prejudice to the parties of permitting or prohibiting further disclosures.

In addition to attorney-client privilege, information may be protected by the work-product doctrine. The work-product doctrine is broader than attorney-client privilege and protects any documents prepared in anticipation of litigation by or for the attorney. The work-product doctrine seeks to allow an attorney the ability to:

- assemble information;

- prepare legal theories and strategies; and

- protect a client's interests.

The doctrine's broadest protection is reserved for materials that reveal the legal strategies or mental impressions of an attorney. However, the work-product doctrine is a qualified evidentiary protection and may be overcome by a showing of substantial need. Also, like attorney-client privilege, the protections of the doctrine may be waived by voluntary disclosure.

7 Evidence

7.1 What procedure(s) exist for collecting and presenting evidence in patent infringement litigation?

In the United States, patent owners have a duty to make a reasonable investigation into the facts underlying their claims before initiating a patent suit. A saisie-contrefaçon procedure similar to that available in France does not exist; nor do federal district courts permit compulsory pre-complaint discovery from an alleged infringer. After a complaint is filed, fact discovery in the United States is broad and more intensive than in other countries. Parties may serve on each other:

- requests for documents;

- requests for admissions;

- requests to inspect property or other items;

- interrogatories; and

- requests for deposition.

7.2 What types of evidence are permissible in your jurisdiction? Is expert evidence accepted?

The scope of permissible discovery and evidence gathering in the United States is broad, allowing the discovery of documents and information regarding any non-privileged matter that is relevant to any party's claim or defence. There are numerous discovery tools available to collect various forms of evidence, such as:

- requests for admissions;

- requests for the production of documents;

- depositions for live witness testimony;

- inspection of premises or things; and

- interrogatory responses.

Expert testimony is also accepted and often used by a party to support its positions relevant to issues such as infringement and validity.

7.3 What are the applicable standards of proof?

In a district court action, the applicable standard for establishing infringement is a preponderance of the evidence (ie, that it is more likely than not). This standard is applied when assessing whether there is direct infringement or indirect infringement by the defendant. With respect to validity, issued patents are presumed valid by statute. Therefore, in order to show that a patent is invalid, the accused infringer must prove by clear and convincing evidence that the patent fails one of the requirements for patentability in 35 USC Sections 101, 102, 103 and 112. The clear and convincing standard is higher than the preponderance of the evidence standard and requires a showing by evidence that is highly and substantially more likely to be true than untrue.

7.4 On whom does the burden of proof rest?

In a district court action for patent infringement, the burden of proof rests with the patent owner-plaintiff to show infringement. The burden of proof to show invalidity and other defences rests with the accused infringer-defendant. At the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), the petitioner has the ultimate burden of showing unpatentability of a challenged claim. However, because there is no presumption of validity at the PTAB, the burden of proof is lower than that applied in a district court action – that is, the PTAB requires a showing by a preponderance of the evidence, which is more favourable to a petitioner than the clear and convincing evidence standard applied in a district court action.

8 Claim construction

8.1 Is there a procedure for construing claims during a patent infringement action? If so, when and how is it performed?

Claim construction proceedings are commonly referred to as Markman proceedings, after a Supreme Court decision holding that claim construction is a question of law for the judge. A claim construction hearing usually takes place after the parties submit briefing on the disputed claim terms and within one year of filing of the complaint. The hearing is conducted by a judge without a jury. The outcome of a Markman hearing can sometimes dispose of a case because, depending on the court's claim construction, the outcome of a dispute regarding infringement and/or validity may be effectively resolved.

8.2 What is the legal standard used to define disputed claim terms?

To construe a claim, the perspective of a person of ordinary skill in the art at the date of the invention is applied by the court. Generally, the language of the claim is construed by giving the words of the claim their plain and ordinary meaning as used in the field of the invention, unless it appears from the written description or prosecution history of the patent that the inventor has assigned and explained a special or specific meaning for the words.

8.3 What evidence does the court consider in defining the claim terms?

To construe a claim, a judge will focus primarily on the intrinsic evidence related to the patent – that is:

- the claim language;

- the specification; and

- the prosecution history.

Even if the meaning of the claim terms appears clear from just the claim language, an examination of the patent specification may reveal a special definition given to a claim term by the inventor that differs from the meaning that it would otherwise possess. In such cases, the inventor's lexicography governs. In addition to consulting the specification, the court will review the patent's prosecution history, if in evidence. Statements made during prosecution that disclaim or disavow a particular claim interpretation to obtain a patent will limit the scope of the claims. Further, amendments and arguments made by the patent owner in the prosecution history can demonstrate relinquishment of a particular claim interpretation, even where the written description supports that claim interpretation. With respect to extrinsic evidence (eg, dictionary definitions or expert testimony), it is deemed less relevant but can be used, for example, to show the state of the art.

8.4 Can the claims of a patent be amended in the course of the proceedings?

The claims of an issued patent cannot be amended during a litigation in a district court. At the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), a patent owner may file a motion to amend and present proposed claim amendments. The panel presiding over the PTAB proceeding may grant or deny the motion. Historically, few motions to amended have been granted. Any proposed amendments cannot expand the claims but only narrow or clarify them. Additionally, the amendment must be responsive to unpatentability issues raised in the proceeding, although ancillary amendments may be allowed.

9 Defences and counterclaims

9.1 What defences are typically available in patent litigation?

In the United States, issued patents are presumed valid by the courts. The burden rests on the plaintiff-patent owner to prove infringement. The primary defences raised by a defendant-alleged infringer to patent infringement claims are non-infringement and invalidity. Examples of other affirmative defences include:

- laches (based on delay of bringing the suit);

- equitable estoppel (based on misleading statements and/or other conduct by the patent owner towards the defendant);

- inequitable conduct (based on misleading statements and/or other conduct by the patent owner toward the US Patent and Trademark Office); and

- exhaustion (based on an authorised licence or sale by the patent owner).

9.2 Can the defendant counterclaim for revocation or invalidation of the patent? If so, on what grounds and what is the process for doing so?

In patent litigation, a defendant may counterclaim that the patent is invalid for failing to meet one or more of the requirements for patentability in 35 USC Sections 101, 102, 103 and 112. The counterclaim is typically made as part of the defendant's answer to the complaint. Once asserted by the defendant, the invalidity counterclaims will be examined together with infringement claims in the litigation for the patent. To challenge the patentability of an issued patent, the defendant may also file a petition for a post-grant review or an inter partes review (IPR) at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board. In an IPR proceeding, the grounds for challenging the validity of the patent are limited to assertions of unpatentability under 35 USC Sections 102 and 103 (anticipation and obviousness) based on published patents or other prior art documents.

9.3 Are there any grounds on which an otherwise valid patent may be deemed unenforceable against a defendant?

Even if a valid patent is infringed, an inequitable conduct defence may be raised by the defendant. Inequitable conduct may be found if the patent owner and/or attorneys involved in the prosecution of the patent violated the duty of disclosure to the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) under 37 CFR Section 1.56. The underlying principle is that one should not be rewarded with a patent obtained through fraud or misrepresentation. Thus, if inequitable conduct is established due to a material omission or misrepresentation with intent to deceive the USPTO, the patent will be held unenforceable.

10 Settlement

10.1 Are mediation and/or other forms of settlement discussions required by the court in your jurisdiction or merely optional to the parties?

Many courts require the parties to engage in some form of settlement discussions at least once before a patent case goes to trial. The requirements for such settlement discussions will often be set forth in the case schedule and/or the court's local rules.

10.2 Can the proceedings be stayed or discontinued in view of settlement discussions?

In some cases, it may be appropriate to stay a case or the proceedings if the parties have reached a settlement in principle or are close to settling their disputes. In a district court action, the parties may file a joint motion to stay the litigation for a proposed amount of time to enable them to finalise a settlement. After a settlement is reached, the case is typically dismissed, with or without prejudice depending on the terms of the settlement. With respect to a post-grant review or an inter partes review at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board, such a proceeding may also be terminated in view of a settlement between the parties, but the Board has discretion to proceed to a final written decision (35 USC Section 317(a)/Section 327(a)).

10.3 Is it necessary to report the results of settlement discussions to the court? If so, how; and what are the implications?

The procedures for mandatory settlement discussions in most district courts often include a reporting requirement. Typically, the parties will be required to report the status or results of settlement discussions to the court via a joint report, letter or other form of submission. In cases where a stay of the litigation is granted in view of settlement discussions, the order granting the stay will often include a requirement that the parties report the status or results of those settlement discussions by a specific date and/or to continue the stay.

11 Court proceedings for infringement and validity

11.1 Are court proceedings in your jurisdiction public or private? If public, are any options available to the parties to keep the proceedings or related information confidential?

Court proceedings in the United States are generally public. In some cases, it may be possible to request to have public access to a courtroom sealed or restricted due to the presentation of trade secrets or highly confidential information. However, not all district courts take a common view on the right to seal a courtroom. As an alternative, it may be possible to protect such confidential information in an open courtroom by, for example, restricting access to relevant documents and demonstratives to the judge and jury and/or sealing exhibits.

11.2 Procedurally, what are the main steps in patent infringement proceedings in your jurisdiction? Is patent validity handled in the same proceedings as infringement or is it handled separately? If separate validity proceedings are available, what are the main steps in those proceedings?

In the United States, a patent lawsuit may be initiated by filing a complaint in a federal district court. There are 94 federal district courts in the United States. A single judge will preside over a patent case, which often includes issues related to infringement and validity. With the exception of abbreviated new drug application litigation, a party may request a trial by jury. After filing of the complaint, there is typically a scheduling conference before the court and an exchange of initial disclosures by the parties. Fact discovery is then conducted, with claim construction briefing and a Markman hearing before the court. Expert discovery then follows, with the exchange of expert reports on disputed issues, including infringement, validity and damages. Pre-trial motions are filed by the parties along with any summary judgment motions filed at this time or earlier. After a pre-trial conference and ruling on the motions by the judge, the trial will be conducted and then a final judgment on the merits will be entered.

Separately, a defendant may challenge the patentability of an issued patent by filing a petition for a post-grant review (PGR) or an inter partes review (IPR) at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). If the petition is granted and the proceeding is instituted by the PTAB, the defendant may file a motion to stay the underlying patent litigation; but the district court has the discretion to grant or deny the stay and may weigh factors such as the status of the litigation and relative timing of a final decision from the PTAB, including any appeal. PGR and IPR proceedings involve limited briefing and discovery (primarily of expert witnesses) and the total time from the grant of the petition to a final written decision by statute is 12 months (with the possibility of extending to 18 months). An appeal of that decision to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit typically takes another one to 1.5 years.

11.3 What is the typical timeframe for patent infringement proceedings? If separate patent validity proceedings are available, with is the typical timeframe for those proceedings?

The time from filing a patent lawsuit to a first-instance decision varies across US district courts. On average, it can take three to four years from the filing of a complaint to a decision on the merits following a trial. In some district courts, the timeline can be shorter, while in other courts it may be longer. In the United States, a single decision by trial usually includes a verdict covering infringement, validity, and damages. Following a first-instance decision, either party may appeal to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC). The CAFC can affirm, reverse, revise and/or remand the decision.

In terms of separate patentability challenges at the PTAB, those proceedings can be conducted in parallel with a district court litigation involving the same patent. If the proceeding is instituted by the PTAB, the district court has the discretion to the stay the litigation pending the outcome of the PTAB proceeding. The total time from the grant of the petition to a final written decision by statute is 12 months (with the possibility of extending to 18 months). An appeal of that decision to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit typically takes another one to 1.5 years.

11.4 To what extent do the decisions of national or foreign courts or bodies influence the court's decision?

Decisions from other domestic jurisdictions (eg, federal courts in other states) have persuasive authority but are not mandatory precedent. Exceptions include doctrines such as collateral estoppel and res judicata. These doctrines may bind parties to findings of law or fact in one jurisdiction to the same findings if the parties try to relitigate the issues in the same or another jurisdiction. Decisions from outside the United States can also be noted but tend not to be influential due to differences in the law.

12 Remedies

12.1 What remedies for infringement are available to a patent holder in your jurisdiction?

Liability for patent infringement in the United States is civil in nature and there is no criminal liability. Available remedies for patent infringement include:

- monetary damages;

- preliminary and permanent injunctions; and

- attorneys' fees.

12.2 Are punitive or enhanced damages available in your jurisdiction? If so, how are they determined?

In addition to compensatory damages, district courts in the United States have the authority to grant punitive damages. In a patent case, a court can increase the damages up to three times the amount found or assessed (so-called 'treble damages'). Typically, increased damages are granted for acts of wilful infringement. According to the Supreme Court, enhanced damages should be reserved for "egregious cases" typified by wilful misconduct by the alleged infringer.

12.3 What factors will the courts consider when deciding on the quantum of damages?

The general rule for determining compensatory damages to a patent owner is to determine the amount of infringing sales and profits lost because of the infringement. If the patent owner has no lost sales, it is still entitled to no less than a reasonable royalty based on the amount of infringing sales. Numerous factors are applied to determine a reasonable royalty, including:

- the royalties received by the patent owner for prior licences to the patent;

- the rates paid for other patents comparable to the asserted patent; and

- the profitability of products made under the patent.

During trial, expert testimony on damages may be presented, including relevant evidence for determining a reasonable royalty or lost profits. Pre-judgment interest and post-judgment interest are also available to compensate the patent owner based on the lost time-value of money it should have received.

13 Appeals

13.1 Can the decision of a first instance court or body be appealed? If so, on what grounds and what is the process for doing so? Please also describe the availability and process for additional levels of appeal.

Appeals based on substantive patent law from the district courts, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB), and the International Trade Commission (ITC) are all heard exclusively by the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC), which is located in Washington DC. Typically, all or part of a decision of a final judgment may be appealed. If a party does not preserve its rights on an issue in the court of first instance, an appeal of that issue may be waived. While a final first-instance judgment is usually required, exceptions exist for particular issues, such as decisions on injunctive relief. With respect to the PTAB, a decision on whether to institute or deny a petition challenging an issued patent is not appealable to the CAFC. Decisions of the CAFC can be appealed to the Supreme Court by way petition for certiorari; however, the Supreme Court has discretion over which cases it hears and only grants such petitions in limited cases.

13.2 What is the average time for each level of appeal in your jurisdiction?

The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC) has exclusive jurisdiction to hear appeals regarding first-instance decisions in patent cases from the district courts, the PTAB and the ITC. Presently, the average time for a decision from the CAFC is 14 to 16 months. The Supreme Court is the final level of appeal for patent disputes, but there is no right to an appeal at this level and a petition for certiorari must be filed. Even if a petition for certiorari is granted (which is rare for patent cases), the time for the appeal can vary widely from case to case, as there is no fixed timeline for the Supreme Court to issue a decision and various factors can influence the overall time to a final opinion.

14 Costs, fees and funding

14.1 What costs and fees are incurred when litigating in your jurisdiction? Can the winning party recover its costs?

The cost of first-instance patent infringement litigation in a US federal district court can vary depending on a number of factors, including:

- the complexity of the technology;

- the level of required discovery;

- the claims at issue in the case;

- the selected forum; and

- the expected timeline to trial.

As an example, litigants in a patent case should budget $4 million or more (per side) through trial. As mentioned, infringement, validity and damages can be determined in one trial. The parties will need to find and pay for their own experts. Also, there will be costs associated with travel, depositions and conducting the trial.

When it comes to recovering costs, there is no 'loser pays' rule in the United States. Reimbursement of costs and attorneys' fees is possible, but the recovery is not awarded as a matter of course to the prevailing party and is at the judge's discretion. For attorneys' fees to be awarded, the case must be found to have special circumstances (eg, frivolous positions or the withholding or destruction of evidence by the other side) such that it that stands out from others with respect to the substantive strength of a party's litigating position or the unreasonable manner in which the case was litigated.

14.2 Are contingency fee and/or other alternative fee arrangements permitted in your jurisdiction?

Contingency fee and/or other alternative fee arrangements are permitted in the United States. Such arrangements are used by practising and non-practising entities to bring patent infringement actions.

14.3 Is third-party litigation funding permitted in your jurisdiction?

Third-party litigation funding is permitted in the United States and used for financing patent infringement actions by a wide variety of patent owners. It is not specifically regulated under US federal law; nor are there requirements to disclose litigation funding agreements to a district court (eg, for purposes of disclosure or approval). However, there can be cases where a court requires its disclosure and/or it may be relevant to issues in the case and discoverable by the other party.

15 Trends and predictions

15.1 How would you describe the current patent litigation landscape and prevailing trends in your jurisdiction? Are any new developments anticipated in the next 12 months, including any proposed legislative reforms?

The United States continues to be a litigious jurisdiction for patent disputes. The number of patent infringement cases filed annually is among the highest among all jurisdictions globally. There is proposed legislation to address issues related to subject matter eligibility under 35 USC Section 101 and to institute certain reforms for proceedings before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). Additionally, a bill was recently introduced to curtail use of the International Trade Commission by non-practising entities. Whether these bills will be passed into law is yet to seen, but patent owners and future litigants should monitor the legislative front as these bills could impact litigation in the United States.

16 Tips and traps

16.1 What would be your recommendations to parties facing patent litigation in your jurisdiction and what potential pitfalls would you highlight?

Parties seeking to litigate in the United States should choose their forum wisely. Certain district courts have local rules and practices that can greatly benefit particular litigants and claims. Also, litigants should be prepared in the event that a patentability challenge is filed in the Patent Trial and Appeal Board, as a parallel proceeding in this forum can result in a stay or change the outcome with regard to the underlying district court litigation. Lastly, discovery is a large part of litigation in the United States and cannot be overlooked. A discovery plan should be prepared in advance of a suit by a plaintiff or immediately after a complaint is filed by a defendant to assess the strength of its claims and confirm what evidence will be needed to advance its positions.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.