The contract disputes now emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic are sure to lead to litigation in both courts and arbitral tribunals involving a wide range of businesses and industries. This litigation will raise novel issues requiring practical guidance on how companies can best position themselves to achieve favorable outcomes in COVID-19 contract disputes. The key issues relate not only to affirmative defenses and burdens of proof but also to the nature of relevant evidence, the importance of expert testimony and the major themes of winning strategies.

I. Defenses Excusing Failure To Perform

The litigation of most COVID-19 contract disputes will focus largely on whether the pandemic or its related effects provide a defense for the nonperforming party's alleged breach. In many cases, the underlying contract will contain provisions addressing unforeseeable events that prevent or impede performance.

For example, the contract may contain a force majeure clause that relieves a party of liability if certain unforeseeable events beyond the party's control-e.g., "acts of God," "acts of war" or governmental actions-prevent performance. Alternatively, in some contracts, especially in loan, real estate or leasing agreements, the parties will specify that a "material adverse event" or other form of "hardship" can provide grounds for either re-negotiating or terminating the agreement.1 Finally, in addition to contract-based defenses, some common law jurisdictions recognize a breach of contract defense based on "impossibility of performance" or "frustration of purpose."2

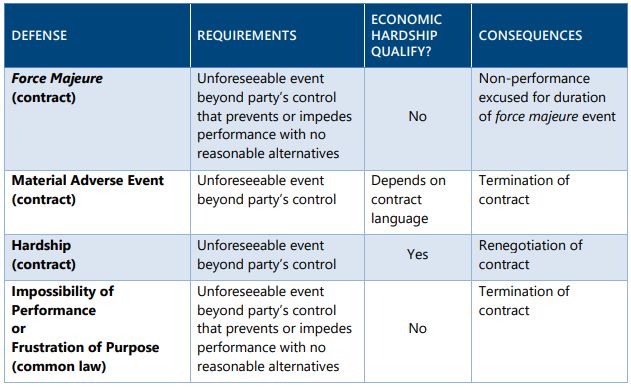

As shown below, these defenses have several elements in common, with the most important being a requirement that the "triggering event" be both unforeseeable and beyond the non-performing party's control. At the same time, the defenses have important differences, such as whether a party's "economic hardship" is sufficient to invoke the defense:

Although the litigation of these defenses will involve widely varying facts and different governing laws, they will also raise many common issues and implicate similar themes for litigation strategies.

II. Defining the Triggering Event

The first issue likely to arise in any pandemic-related contract litigation is whether the claimed "triggering event" qualifies as an occurrence excusing non-performance (assuming all other requirements are met). Predictably, the non-performing party will invoke either the pandemic itself or a specific government restriction (or a combination of both) as the event excusing non-performance.

In the case of contracts formed after the first reports of COVID-19, the parties are likely to dispute whether the pandemic (or any subsequent government action) was sufficiently "unforeseeable" to qualify as a triggering event. On this issue, the date of contract formation will be critical in assessing the information available to both parties about the emerging pandemic.

By contrast, in the case of contracts formed before the first reports of COVID-19, the non-performing party will likely be able to show that the pandemic (or its effects) constituted an unforeseeable occurrence that was beyond its control. Indeed, in many cases, the contract will contain a force majeure provision that expressly applies to "epidemics," "acts of government" or, more generally, "other events beyond the party's control."

The definition of the triggering event is important not only for assessing its "unforeseeability" but also for determining its duration and the scope of its effects-factual questions that carry important implications for other issues likely to be litigated in the dispute.

III. Causation

To establish a valid defense, a non-performing party must also show that the triggering event was the "proximate cause" of its inability to perform a specific contractual duty.3 To this end, the nonperforming party must satisfy three separate but closely related "causation" elements: (1) a direct causal link between the triggering event and non-performance, (2) due diligence in avoiding the effects of the triggering event and (3) exhaustion of all reasonable alternatives to non-performance.

A. THE CAUSAL LINK REQUIREMENT

The first requirement focuses on whether a causal link exists between the triggering event and the inability to perform a contractual obligation. On this issue, the non-performing party will bear the burden of proof. In the case of contract-based defenses (e.g., force majeure), the necessary quantum of proof will depend in part on whether the contract requires the triggering event to "prevent" performance or merely "impede" or "delay" performance. It will also depend on whether the relevant provision requires a showing of "but for" causation or some lesser showing of causation.

In most cases, the triggering event must directly prevent or impede the party from completing performance, not simply create economic conditions that make performance impracticable. A major exception to this rule is a contract provision that specifically identifies economic hardship as a qualifying event. Absent such a provision, courts and tribunals generally hold that economic hardship does not excuse non-performance-even when the hardship is the direct result of a force majeure event.4

Consequently, in most COVID-19 disputes, the non-performing party will have to show more than economic hardship to establish the requisite causation. In some cases, the non-performing party's ability to carry this burden will depend on whether it can cite a governmental act as the triggering event, rather than the pandemic itself. A governmental act not only carries the force of law but also has a well-defined scope that facilitates the causation analysis. For example, a concert promoter could plausibly claim that a government ban on public gatherings directly prevented it from going forward with a scheduled concert. By contrast, if the triggering event is the pandemic itself, the causal link with nonperformance may be more attenuated and may involve elements of economic hardship, such as a decline in demand for the relevant goods or services.

Nevertheless, in many COVID-19 litigations, the non-performing party will be able to make at least a prima facie showing (based on both fact and expert testimony) that either a government lockdown or the pandemic itself was the proximate cause for its nonperformance.5 The factual predicate for this showing could take many forms, including a quarantined labor force, an inability to obtain a needed government permit, supply chain disruptions or other factors. In these cases, the litigation will focus not only on the adequacy of the "causal link" but also on whether other causes contributed to the non-performance.

B. COULD THE EFFECTS HAVE BEEN AVOIDED?

The second requirement focuses on whether the non-performing party could have avoided the effects of the triggering event through the exercise of due diligence. This requirement rests on the recognition that the effects of a triggering event can sometimes be avoided, even though the event itself is "unforeseeable." If the non-performing party's own lack of diligence prevented it from avoiding the effects of the triggering event, a tribunal will likely decline to excuse non-performance.

To view the full article, please click here.

Footnotes

1 See, e.g., Akorn, Inc. v. Fresenius Kabi AG, 2018 WL 4719347, at * 53 (Del. Ch. Oct, 1, 2018).

2 See, e.g., Kel Kim Corp. v. Central Markets, Inc., 70 N.Y. 2d 900, 902 (1987).

3 Hong Kong Islands Line Am. S.A. v. Distribution Servs., Ltd., 795 F. Supp. 983, 989 (C.D. Ca. 1991).

4 In re Millers \Cove Energy Co., Inc., 62 F.3d 155, 158 (6th Cir. 1995); OWBR Lv. Clear Channel Communications, Inc. LLC, 266 F. Supp. 2d 1214 (D. Hawaii 2003).

5 C. Brunner, "Rules on Force Majeure as Illustrated in Recent Case Law," Sec. III. G., Hardship and Force Majeure in Commercial Contracts, F. Bartolotti and D. Ufot (eds.), International Chamber of Commerce (2018).

Originally published 4 May, 2020

Visit us at mayerbrown.com

Mayer Brown is a global legal services provider comprising legal practices that are separate entities (the "Mayer Brown Practices"). The Mayer Brown Practices are: Mayer Brown LLP and Mayer Brown Europe – Brussels LLP, both limited liability partnerships established in Illinois USA; Mayer Brown International LLP, a limited liability partnership incorporated in England and Wales (authorized and regulated by the Solicitors Regulation Authority and registered in England and Wales number OC 303359); Mayer Brown, a SELAS established in France; Mayer Brown JSM, a Hong Kong partnership and its associated entities in Asia; and Tauil & Chequer Advogados, a Brazilian law partnership with which Mayer Brown is associated. "Mayer Brown" and the Mayer Brown logo are the trademarks of the Mayer Brown Practices in their respective jurisdictions.

© Copyright 2020. The Mayer Brown Practices. All rights reserved.

This Mayer Brown article provides information and comments on legal issues and developments of interest. The foregoing is not a comprehensive treatment of the subject matter covered and is not intended to provide legal advice. Readers should seek specific legal advice before taking any action with respect to the matters discussed herein.