In the early 1980s, Jimmy Smith, an American jazz musician of some renown, recorded the album Off the Top, consisting of six instrumental jazz recordings and a spoken-word piece titled "Jimmy Smith Rap." In his rap, Smith shares the behind-the-scenes story of how Off the Top got made, explaining that he and his collaborators had decided to make "a straight edge Jazz" record because "jazz is the only real music that's gonna last." Smith died in 2005. The plaintiffs are the successors in interest to the copyright in "Jimmy Smith Rap."

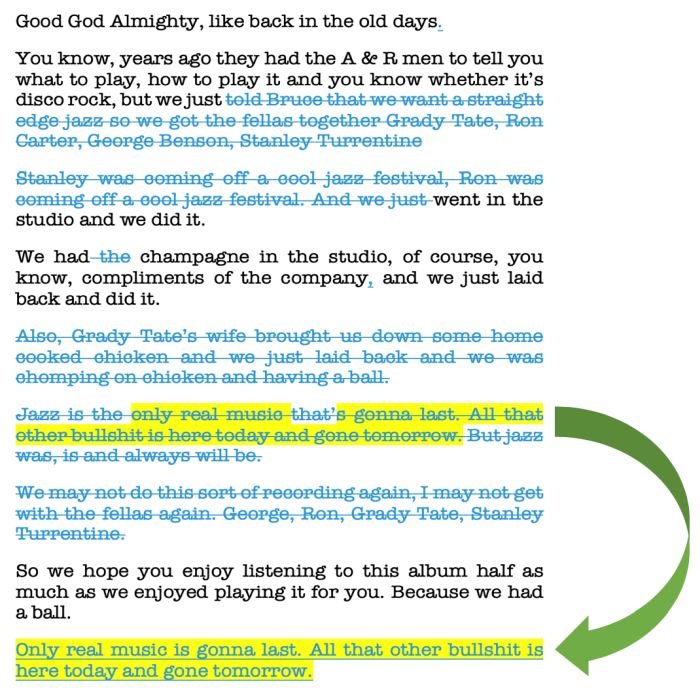

In 2013, Drake, a Canadian musician of some renown, released the song "Pound Cake/Paris Morton Music 2" ("Pound Cake"), featuring vocals by Jay Z, a Brooklyn recording artist of some renown. Pound Cake opens with a 35-second sample from "Jimmy Smith Rap." Drake edited out about half of Smith's original words, changed "jazz is the only real music that's gonna last" to "only real music is gonna last," and reordered things so the modified phrase comes at the very end of the sample. This redline shows Drake's modifications:

Interesting fact: Drake and the other defendants obtained a license to use the sound recording of "Jimmy Smith Rap," but not the underlying composition. Why? Perhaps because Smith never secured a copyright registration for the work during his lifetime. Indeed, the plaintiffs only obtained a registration after Drake's album dropped. (More about that in a minute.) With registration in hand, the plaintiff's sued.

The district court granted summary judgment for Drake and the

other defendants on fair use grounds. The Second Circuit affirmed

in a summary decision. Here's a rundown of the court's

decision.

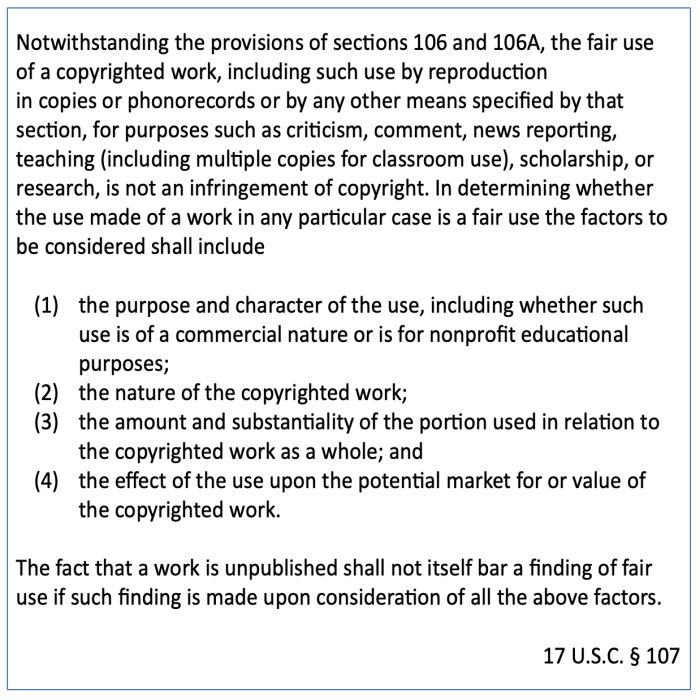

Purpose and Character of Use. The Second Circuit agreed with the district court that Drake's use of "Jimmy Smith Rap" in "Pound Cake" was transformative and that, therefore, the first fair use factor favored the defendants. According to the court, "Jimmy Smith's Rap" conveys a message "about the supremacy of jazz to the derogation of other types of music." (In Smith's own words, jazz is "the only real music that's gonna last.") By contrast, in "Pound Cake," Drake conveys what the court describes as a "counter message": that all "real music," regardless of genre, reigns supreme. Drake achieves his "counter message" by carefully editing Smith's words and placing them in the context of (and at the very beginning of) a nearly seven-minute long song in which Drake and Jay-Z rap about the greatness and authenticity of their work. As a result, Drake "criticizes the jazz-elitism that the 'Jimmy Smith Rap" espouses' and therefore uses the copyrighted sample "for a purpose ... different from that for which it was created."

It's worth pausing here for a moment. To the best of my knowledge, Smith's rap is beyond obscure - the deepest of deep cuts. I don't think I am going out on a limb by saying that it is highly unlikely that fans of "Pound Cake" would have any idea that Smith ever walked the face of the Goddess's green earth, let alone that he penned "Jimmy Smith's Rap." I bet that even someone familiar with "Jimmy Smith Rap" in its original form would be hard pressed to recognize the subtle changes made by Drake. And certainly anyone listening to Drake's modifications of Smith's rap, without the benefit of this background knowledge, would have absolutely no idea that Drake is engaging in a debate with Smith about the supremacy of Jazz vs other genres. Doesn't this mean that Drake is, essentially, shadow boxing? If my suppositions are right (and, of course, I think they are), can this truly be a transformative use?

The Second Circuit didn't address this question, but, fortunately, the district did. To the district court, the obscurity of "Jimmy Smith Rap" was irrelevant because "Pound Cake" was not a parody under Campbell v. Acuff Rose, 510 U.S. 569 (1994). In the district court's words:

Although it is certainly true that the object of a parody must be ascertainable to the average observer - and with reason, for what good is parody if the listener cannot identify the target of derision? - this is not a universal prerequisite for finding a transformative use.

The district court cited as support Blanch v. Koons, 467 F.3d 244, 252 (2d Cir. 2006). where the Second Circuit found that appropriation artist Jeff Koons' use, without permission, of a small portion of a print ad in a larger mixed-media artwork was a transformative use even though no reasonable observer could possibly identify the source of the original content. To the district court, the critical question was not whether the average listener would understand "Pound Cake" to be a dialog between Drake and Smith about the supremacy of one genre of music over another; instead, the issue was whether the average listener of "Pound Cake" would understand the sample, as modified by Drake, as a statement that "only real music is gonna last." Because the district court found that the average listener would have this understanding (how could she not, since that is literally what the text, edited by Drake, says?), the court concluded that Drake's purpose for using the sample was "sharply different" from Smith's purpose in creating the original track, and that therefore the use was transformative.

So, in a nutshell, Drake is the Jeff Koons of hop hop; like Koons, he used the copyrighted work of another as "raw material" that he bends to his will "in furtherance of distinct creative or communicative objectives."

Nature of the Copyrighted Work. The district court had found that the second factor weighed against a finding of fair use because "Jimmy Smith Rap" is a work of creative expression. While the Second Circuit did not disturb that holding, it noted that the second factor is of "limited usefulness," in light of its finding that 'Jimmy Smith Rap' is being used for a transformative purpose."

Amount and Substantiality of Portion Used. The court found that the third factor supported fair use because the amount of "Jimmy Smith Rap" used by the defendants was reasonable both quantitatively and qualitatively. Here, in addition to using Smith's words about the supremacy of Jazz (which was directly related to his "counter message") Drake also appropriated content about the production process for Off the Top (which arguably went beyond what Drake needed). Noting that the law does not require that the secondary artist take no more than is necessary, the court found that Drake's borrowing of language detailing the production process for Off the Top "was necessary" to emphasize the message that "the ultimate attribute of music is its authenticity, not the production process that created it."

Effect on the Market. Finally, the court found that the fourth factor also weighed in favor of fair use. There was no evidence that "Pound Cake" would usurp demand for "Jimmy Smith Rap" or otherwise negatively impact the market for "Jimmy Smith Rap." The works are aimed at different audiences (hip hop fans for Drake's, and and jazz aficionados for Smith's), and there was no evidence of the existence of an active market for "Jimmy Smith Rap," which the court described as "vital for defeating Defendants' fair use defense." And while the Second Circuit didn't mention this (although the district court did), it is telling that the plaintiffs never attempted to establish a market for derivative uses of "Jimmy Smith Rap" until after the defendants used the recording on "Pound Cake."

Estate of Smith v. Graham, 2020 WL 522013, __ Fed. Appx. __ (2nd Cir. Feb. 3, 2020)

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.