This is part of a series of articles discussing recent orders of interest issued in IP cases by the United States District Courts in the Southeast.

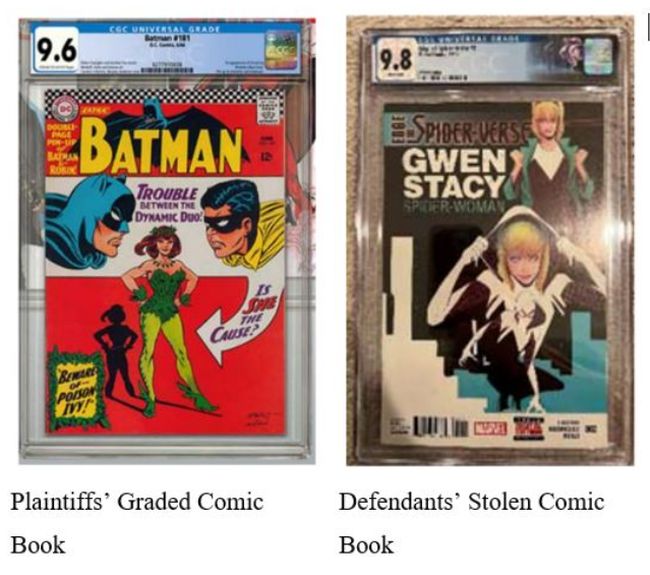

In Certified Collectibles Group, LLC v. Terrazas, No. 8:24-cv-00301-KKM-AAS (M.D. Fla. Feb. 7, 2024), Judge Mizelle granted Plaintiffs Certified Collectibles Group, LLC ("CCG") and Certified Guaranty Company, LLC's ("CGC") motion for an ex parte temporary restraining order against Defendants Brandon and Ayana Terrazas, two of its former employees, from engaging in a fraudulent scheme of selling collectible comic books bearing CGC's trademarks under pseudonyms online.

CGC is an industry leader for authenticating and grading pop culture collectibles such as comic books. CGC was the first of its kind to establish its own comic book grading system, allowing such comic books to be authenticated and graded by its grading experts and valued for collecting, trading, and selling. Each certified and authenticated comic book is graded on a scale from 0.5 to 10 and labeled based on the grade or other pertinent attributes of the comic book. For example, the labels vary in color (i.e., Universal Label (Blue), CGC Signature Series Label (Yellow), Qualified Label (Green), Restored Label (Purple), and Pedigree Label (Gold)) and description (i.e., "fine," "fine/very fine," and "mint"). A label that contains the CGC SIGNATURE SERIES® trademark signifies that the owner of the comic book had it signed by the comic book artist.

The Terrazas engaged in a fraudulent scheme by "stealing customers' comic books from CGC's facilities, generating duplicates of legitimate, authenticated CGC grade labels belonging to highly valuable comic books, encapsulating less valuable, lower grade comic books with these higher value duplicate labels, and offering such mislabeled goods to the public at large." As a result of this scheme, consumers searching for or purchasing CGC-graded comic books received a lower graded comic book with a duplicate, higher-graded CGC label taken from another (higher graded) book. Brandon Terrazas confessed to stealing 23 customer-submitted comic books and received at least $26,895 from his scheme of regrading and selling Plaintiffs' comic books.

The court found that CGC and CCG demonstrated a "strong probability" of proving at trial that consumers are likely to be confused by the Terrazas's conduct and by the comic books that bear "identical" CGC trademarks. The court also found that CGC and CCG were presumed to likely suffer irreparable harm absent a temporary restraining order. The court found that any potential harm to the Terrazas was outweighed by the potential harm to CGC and CCG and that the public interest favored protecting CGC's trademark interests, encouraging respect for the law, and protecting the public from being defrauded by the illegal sale of counterfeit goods. As a result, the court granted Plaintiffs' motion for a temporary restraining order until the hearing for a preliminary injunction.

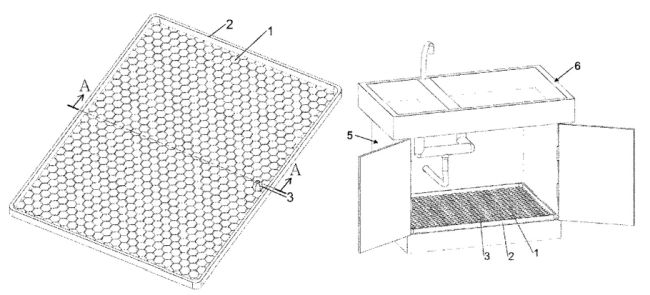

In Shenzhen Hengzechen Technology Co., Ltd., v. The Individuals, Partnerships, and Unincorporated Associations identified on Schedule "A," No. 1:23-cv-23380 (S.D. Fla. Feb. 7, 2024), Judge Scola, Jr. granted in part a motion to dismiss for failure to mark patented items or provide the required notice under 35 U.S.C. § 287. The court also dismissed the claim for design patent infringement under 35 U.S.C. § 289.

Plaintiff Shenzhen Hengzechen Technology ("Shenzhen") sued eighty defendants for infringement of US Patent No. 11,559,140. The '140 patent relates to a waterproof pad with a drainage hole designed to go underneath sinks to prevent water damage caused by a leak.

Four defendants moved to dismiss under Rule 12(b)(6) based on two grounds: (1) the complaint failed to plead compliance with the marking or notice requirement under 35 U.S.C. § 287 and (2) Shenzhen could not recover damages for infringement of a design patent under 35 U.S.C. § 289 because the '140 Patent is a utility patent.

Under 35 U.S.C. § 287, a patentee is barred from recovering damages if they did not mark their patent items or otherwise notify infringers of the alleged infringement. The court agreed that Shenzhen failed to properly plead marking or any pre-suit notice as required under Section 287 because the complaint provided no more than conclusory allegations regarding notice of the patent. Although the court found that filing the lawsuit constituted the requisite notice, the lawsuit was filed under seal, and thus, the court dismissed Shenzhen's claim for all damages prior to the unsealing of the lawsuit and allowed only the claim for damages that accrued after Shenzhen unsealed the complaint.

Under 35 U.S.C. § 289, a patentee has an additional remedy for infringement of a design patent. The court found that Shenzhen acknowledged that the references to Section 289 were "a typographical error" and thus dismissed Shenzhen's claim for design patent infringement.

In Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson v. Lenovo (U.S.), Inc., No. 5:23-CV-00569-BO (E.D.N.C. Feb. 13, 2024), Judge Boyle denied Defendant Lenovo (U.S.), Inc.'s motion for temporary restraining order and anti-suit injunction prohibiting Plaintiff Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson from enforcing foreign injunction orders issued against Lenovo in Colombia and Brazil.

Lenovo and Ericsson both own patents essential to the 5G network, but recent negotiations to enter a global cross-licensing agreement failed. As negotiations between Lenovo and Ericsson over the 5G patents broke down, Ericsson began filing a series of foreign and domestic patent infringement actions, including this case and actions in Columbia and Brazil. The actions in Columbia and Brazil resulted in injunctions preventing Lenovo from selling products that implement the standard essential patents ("SEPs") at issue.

Both Lenovo and Ericsson are members of the European Telecommunications Standard Institute ("ETSI"), the standard development organization primarily responsible for promulgating the 5G standard. Importantly, Clause 6.1 of the ETSI's IP rights policy requires SEP holders to commit to "an irrevocable undertaking in writing that it is prepared to grant irrevocable licenses on fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory ("FRAND") terms and conditions . . . ." However, terms beyond the FRAND commitment, including what constitutes a FRAND rate, are left for the parties to negotiate. Lenovo cast Ericsson's actions in Brazil and Columbia, growing markets for Lenovo's 5G offerings, as an attempt to coerce Lenovo into accepting supra-FRAND terms.

The court first addressed the form equitable relief would take, noting that Lenovo's motion had the procedural trappings of a TRO but the substance of a motion for a preliminary injunction. Pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 65, courts may properly treat a motion for a TRO as a motion for a preliminary injunction, provided the non-moving party has fair opportunity to oppose the motion. Here, the court set a date for the TRO hearing thirteen days after Lenovo filed its motion, "a duration more than sufficient for Ericsson to fairly oppose the motion," and elected to treat Lenovo's motion for a TRO as a motion for a preliminary injunction.

"Although an anti-suit injunction ostensibly operates only against the parties not the foreign court, such an order effectively restricts the jurisdiction of the court of a foreign sovereign." Thus, an anti-suit injunction is not considered under the traditional four-part test for a preliminary injunction. Instead, the propriety of an anti-suit injunction is assessed in three steps.

- "First, the movant must satisfy two threshold requirements: (1) that the parties and issues are the same in both matters and (2) that resolution of the case before the enjoining court is dispositive of the action to be enjoined. . . ."

- "Second, the movant must show that at least one of the anti-suit injunction factors applies. These factors include whether the foreign litigation would (1) frustrate a policy of the forum issuing the injunction; (2) be vexatious or oppressive; (3) threaten the issuing court's in rem or quasi in rem jurisdiction; or (4) where the proceedings prejudice other equitable consideration. . . ."

- Third, if the first two steps are met, "the court assesses the injunction's effect on international comity," which is "the degree of deference that a domestic forum must pay to the act of foreign government not otherwise binding on the forum. In practice, comity serves as the mortar that cements the brick house of the international system."

Regarding the first element of step one, Ericsson argued that Lenovo did not show substantial similarity because the Lenovo entities seeking the anti-suit injunction differ from the Lenovo entities enjoined in Brazil and Columbia. The court disagreed, finding that Lenovo US is substantially similar to the foreign defendants because "Lenovo US has the authority to negotiate with Ericsson to reach a global patent cross-license comprising both Lenovo US's and its related entities essential patents."

However, regarding the second element of step one, the court found that the underlying licensing dispute before the Eastern District of North Carolina would not be dispositive of the Brazilian and Colombian actions, reasoning that if the court finds that Ericsson's past offer is FRAND, Lenovo could choose not to accept it. Thus, "holding the parties to their obligations in the ETSI IP rights policy will not necessarily result in a global cross-license that resolves the foreign patent actions," and "[o]nly the courts of those sovereigns can resolve claims for infringement of their respective patents." As such, the court denied Lenovo's motion without addressing steps two or three.

In Natera, Inc. v. NeoGenomics Labs., Inc., No. 1:23-cv-00629-CCE-JLW (M.D.N.C. Feb. 14, 2024), Chief Judge Eagles denied Defendant NeoGenomics Laboratories, Inc.'s motions to stay the preliminary injunction pending appeal and motion to modify the preliminary junction.

Motion to Stay

As previously reported here, Plaintiff Natera, Inc. obtained a preliminary injunction on December 27, 2023, against NeoGenomics' continued offering and sale of its molecular residual disease ("MRD") product, RaDaR. By its first motion, NeoGenomics asked the court to stay enforcement of the injunction until NeoGenomics' appeal of the preliminary injunction to the Federal Circuit concludes.

To determine whether a stay should be granted, the court reviewed four factors: (1) whether the applicant has shown a likelihood of success on the merits; (2) whether the applicant will be irreparably injured absent a stay; (3) whether a stay will substantially injure other interested parties; and (4) where the public interest lies. NeoGenomics argued it is likely to succeed on the merits, that it will suffer irreparable harm, and that a stay is in the public interest. The court disagreed on each point.

The court disagreed that NeoGenomics demonstrated a likelihood of success. The court found NeoGenomics' arguments that the asserted patents are invalid unpersuasive given the same arguments were made at the preliminary injunction hearing. NeoGenomics likewise contended the court failed to consider its argument the asserted patent was invalid for ineffective written description. The court disagreed, holding it had "no duty to set forth a detailed argument NeoGenomics chose not to make in briefing."

Turning to irreparable harm, NeoGeonomics argued the court legally erred in its analysis. Specifically, NeoGenomics argued the court improperly found that the existence of head-to-head competition, by itself, established irreparable harm and that the court "minimized the harm to NeoGenomics." The court disagreed with NeoGenomics' characterizations, instead holding it made several findings of fact that NeoGenomics ignores. Likewise, the court distinguished its act of weighing the evidence as distinct from "minimizing" the harm to a party.

Finally, NeoGenomics argued the court overlooked the public's interest in "broader availability of medical services and products." The court reiterated the difference between weighing the evidence versus overlooking a factor. Accordingly, the court found all factors weighed against a stay and denied NeoGenomics' motion to stay the preliminary injunction.

Motion to Modify

The preliminary injunction took effect on January 12, 2024. NeoGenomics, by its second motion, moved to modify the breadth of the injunction, arguing NeoGenomics "does not use the [allegedly infringed] method in the United States," and asked the court to remove the prohibition on selling or offering its RaDaR product in the United States from the enjoined activity.

The court highlighted how NeoGenomics put forth no documents or testimony to show the patented methods were being performed outside of the United States. The court admonished NeoGenomics' months-long awareness of Natera's proposed preliminary injunction and found it "did not raise a murmur of opposition to or concern about the language it now challenges." Rather, the court found such an argument can be presented through discovery and raised in briefing for summary judgment or trial. Accordingly, the court denied the motion to modify.

The court concludes its order with a two-page warning to both parties. In its warning, the court stressed the need for parties to file briefs "with clear, specific, thorough, focused, accurate, and helpful discussion," and stated that "[u]nhelpful briefs are a misuse of limited court resources[.]" The court further discouraged motions "that seek a second bite at the apple," finding litigants picking among available arguments to present to the court is just "a necessary and required part of litigation." The warning ends by stating the court "will not hesitate to use" tools at its disposal should the parties continue to file "briefs with confusing and unhelpful sections."

In Electrolysis Prevention Solutions LLC v. Daimler Truck North America LLC, No. 3:21-cv-00171-RJC-WCM (W.D.N.C. Feb. 20, 2024), Judge Metcalf granted in part both Plaintiff Electrolysis Prevention Solutions LLC's ("EPS") motion to strike expert opinions regarding alleged non-infringing alternatives, and Defendant Daimler Truck North America LLC's ("DNTA") motion to exclude certain opinions of EPS's damages expert.

EPS moved to strike DTNA's expert opinions on non-infringing alternatives as untimely because they were identified in the rebuttal reports, and as unreliable for lack of specificity. The court found that, while DTNA's delay in providing details on potential non-infringing alternatives in its interrogatory responses was problematic, DTNA had no obligation to provide expert opinions about non-infringing alternatives prior to filing rebuttal reports. The court further found the identification of non-infringing alternatives based on "certain radiators made and sold to DTNA by TitanX, Modine, or Mahle Behr" were sufficiently specific, and, while the opinions could be more robust, DTNA's expert explained the basis why they were non-infringing and how they were available during the damages period. The court, however, found the expert's identifications of non-infringing alternatives as "radiators with the alleged sacrificial anode eleven inches from the inlet" and "radiators with metals that will resist thermal stress, or with sufficient tube thickness to resist thermal stress, such that tube reinforcement inserts are unnecessary" to be too generic to establish DTNA's position and, therefore, excluded those opinions.

Separately, DTNA moved to exclude EPS's damages expert opinions on reasonable royalty rate as unreliable based on use of inflated retail value of a known prior art product and use of flawed test data and data extrapolations. The court found that the valuation of an alternative product for determining the reasonable royalty rate is more appropriately addressed through cross-examination rather than exclusion, noting that estimating a reasonable royalty is not "an exact science," and there can be multiple reliable methods for calculating a reasonable royalty rate. The court further rejected DTNA's argument that the test data was flawed, because the court previously denied that motion to exclude. (See Southeast Litigation Update: November 2023.) Nonetheless, the court found that EPS's damages expert failed to provide evidentiary support for the extrapolation that an alleged increase of a product's longevity by between 24.4% and 25.1% would result in a corresponding price increase of the same percentage that would be accepted by customers. Accordingly, the court excluded that portion of the damages opinion, noting that opinion evidence connected to existing data only by the ipse dixit of the expert is simply too great an analytical gap between the data and the opinion proffered.

In Endo Par Innovation Co., LLC v. BPI Labs, LLC, No. 8:23-cv-1953-WFJ-TGW (M.D. Fla. Feb. 22, 2024), Judge Fung denied a motion to dismiss, or in the alternative motion for a more definite statement in a patent infringement case.

Both Plaintiffs Endo Par Innovation Co., LLC, Par Pharmaceutical, Inc., and Par Sterile Products (collectively, "Par Innovation") and Defendants BPI Labs, LLC and Belcher Pharmaceuticals, LLC (collectively, "BPI") hold New Drug Applications ("NDAs") for epinephrine-based products, which are used for emergency treatment of anaphylactic reactions. Par Innovation manufactures and sells both 1 mL and 30 mL Adrenalin® brand epinephrine-injection products. BPI sought to supplement its NDA to sell a 30 mL version of its epinephrine injection product, and pursuant to 21 U.S.C. § 355(b)(3), served notice letters to Par Innovation, explaining that Par Innovation's epinephrine-related patents were either invalid or not infringed by BPI's proposed 30 mL epinephrine product.

Under the Hatch-Waxman Act, a plaintiff who receives a Paragraph IV certification (e.g., a "certification" that a patent submitted to Food and Drug Administration ("FDA") by the brand-name drug's sponsor and listed in FDA's Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations (the "Orange Book") is invalid, unenforceable, or will not be infringed by the generic product) may state a claim for infringement by alleging four elements:

- its interest in the patent,

- its receipt of the paragraph IV certification,

- the filing of the NDA, and

- its contention that the defendant's proposed product will infringe.

The court concluded that each of these elements was met under a Rule 12(b)(6) standard, finding that Par Innovation demonstrated sufficient interest in the patents-in-suit and receipt of "paragraph IV certification in the form of the First and Second Notice Letters,"that BPI filed a supplement to its NDA, and that Par Innovation contends that BPI's proposed epinephrine product infringes at least one claim of the '876 patent and '657 patent. The court further found that BPI's notice letters do not render the complaint deficient at the motion to dismiss stage because it must accept as true the complaint's express allegation that the notice letters failed to provide a full and detailed explanation as to why the claims are not invalid or not infringed. The court recognized that these factual arguments may be raised following claim construction and discovery. Moreover, the Court found that the complaint sufficiently put BPI on notice to prepare a responsive pleading, and therefore denied any requested relief for a more definite statement under Rule 12(e).

In Fern Avenue Solutions, LLC v. Protected Solutions, LLC, No. 1:23-CV-2085-SCJ (N.D. Ga. Feb. 27, 2024), Judge Jones lifted a stay of the litigation after both Defendant Protected Solutions, LLC and Plaintiff Fern Avenue Solutions, LLC failed to provide the court with an acceptable reason in response to a show cause order.

The court previously granted a limited 60-day stay that was expressly conditioned on Protected Solutions filing an inter partes review ("IPR") to challenge the patent-in-suit before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board. The court found that, not only did Protected Solutions fail to file an IPR petition, both parties more egregiously failed to inform the court that the filing had not occurred—especially after it should have become patently apparent to Protected Solutions that it would not be able to timely file the petition during the stay period and after it should have become apparent to Fern Avenue Solutions after the 60-day stay period had ran.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.