Enforcement of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) reached unprecedented levels in 2010, as the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) levied double the financial penalties imposed in 2009. Dedicated enforcement units at the DOJ and SEC devoted more resources to sectorwide investigations, resulting in a large-scale settlement with oil- and gas-services companies and a new investigation into the banking industry.

Overseas anti-corruption enforcement activity has also increased. Although it has not yet been implemented, the long-awaited Bribery Act h as been passed by the U.K. and could further expand global anti-corruption enforcement. In addition, other countries are increasingly prosecuting corruption occurring within their borders.

In this heightened regulatory climate, companies must identify high-risk activities while concentrating compliance efforts on mitigating potential violations of law. This article identifies recent trends and developments in anti-corruption enforcement and considers their impact on companies, focusing on the following:

- Aggressive enforcement and record fines. Penalties imposed under the FCPA continue to increase dramatically, including large amounts of disgorged profits.

- Bounties paid to whistleblowers. The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 (Dodd-Frank Act) enacted a new set of rewards and protections for whistleblowers who provide tips to the SEC on fraud and securities violations, including under the FCPA.

- New tools used by enforcement authorities. Enforcement authorities intend to continue targeting industries as a whole, using sectorwide sweeps based on information collected from one company or informant. In addition, the SEC has started to use nonprosecution agreements in its enforcement efforts.

- U.K. Bribery Act and overseas enforcement . The U.K. Bribery Act could change the landscape of anticorruption enforcement , if and when implemented. Beyond the U.K., more countries are initiating enforcement actions against businesses engaged in improper behavior within their borders.

- Enforcement actions against individuals. The DOJ and SEC continue to investigate and charge individual decision makers, not just corporations, with violations of the FCPA.

Aggressive Enforcement and Record Fines

2010 was a record year for FCPA enforcement, and U.S. authorities show no sign of slowing down. In 2010:

- The DOJ imposed a record $1.2 billion in criminal fines in cases related to FCPA violations.

- The SEC recovered approximately $530 million in disgorgement, civil penalties, and prejudgment interest.

The combined recovery total of approximately $1.73 billion is almost twice the $890 million recovered in 2008, which was itself a high-water mark for FCPA penalties by virtue of an $800 million penalty levied that year against a German industrial conglomerate. The 23 corporate enforcement actions resolved during 2010 include six where the total amount of fines, disgorgement, civil penalties, and prejudgment interest exceeded $100 million.

Companies operating in international commerce must be aware of the enormous costs associated with FCPA violations. Because of this, companies should identify high-risk activities and implement comprehensive, systematic compliance controls to avoid enforcement actions.

Companies can identify high-risk countries by reviewing Transparency International's annual Corruption Perceptions Index, which ranks countries by their perceived levels of corruption, based on expert assessments and opinion surveys. In 2010, Denmark, New Zealand, and Singapore were the world's least corrupt countries, and Somalia was ranked the most corrupt for the fourth year in a row. For a table that sets out the 2005–2010 Corruption Perceptions Index rankings for the countries in which some act of bribery led to prosecution under the FCPA, see page 3.

Bounties Paid to Whistleblowers

The new whistleblower provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act are expected to increase the number of enforcement actions against companies that trade on U.S. stock exchanges. Under the new provisions, a whistleblower can collect a bounty for voluntarily providing "original information" regarding securities violations to the SEC. This includes alleged violations of both the anti-bribery and accounting provisions of the FCPA.

Under the new provision, a whistleblower can receive between 10 and 30 percent of monetary sanctions greater than $1 million that result from the information he provides. Payments to whistleblowers are measured by the sanctions imposed by the SEC and those imposed in related actions brought by the DOJ or other agencies. The SEC determines the precise amount of any award within the permitted range, taking into account factors that include:

- The significance of the information received.

- The level of cooperation provided.

The new provisions permit whistleblowers to be represented by counsel. A whistleblower who chooses to provide information anonymously must have an attorney.

Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index

Transparency International's annual Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) ranks countries by their perceived levels of corruption, based on expert assessments and opinion surveys. The following table indicates the CPI ranking for the countries in which some act of bribery led to prosecution under the FCPA.

Because of the personal and professional risk associated with reporting violations, proponents of the whistleblower provisions argue that a financial incentive is necessary to encourage key witnesses to come forward. However, the business community criticized the provisions for encouraging employees and other insiders to bypass internal compliance- reporting structures. To address these concerns, the SEC included in its proposed regulations the ability for the SEC to consider higher rewards for whistleblowers who first report the information through effective company compliance programs. In addition, the proposed regulations prohibit certain categories of persons from reward eligibility, including whistleblowers with a legal or contractual duty to report such information to their employers.

It is too early to predict the impact of these provisions on FCPA enforcement. However, companies familiar with the surge of federal False Claims Act fines since the 1986 liberalization of that law's whistleblower qui tam provisions should note that many of the same plaintiffs' firms have added SEC whistleblower sections to their web sites in anticipation of increased litigation. In addition, the SEC recently reported that the number of "high value" tips it received on fraud and other securities violations had grown from two a month to one or two daily (see "U.S. SEC gets more whistleblower tips," Reuters, February 4, 2011).

New Tools Used by Authorities

Sectorwide Investigations

The record level of recoveries in 2010 is due in large part to the success of sectorwide investigations. U.S. enforcement authorities have been quick to discover links between one corrupt agent and multiple companies, leading to investigations of the entire industry.

Recent actions involved up to a dozen companies at a time in both the energy and medical-devices sectors. This concentration can be attributed to the particular nature of these industries and the regions in which they operate. In addition, the SEC has begun investigating the financial industry. The SEC has also stated that it will continue its focus on sector-wide sweeps in all industries (see "SEC Charges Seven Oil Services and Freight Forwarding Companies for Widespread Bribery of Customs Officials," SEC Release No. 2010-214 (November 4, 2010)).

Energy

Energy companies often operate in some of the most volatile and corrupt regions of the world. Therefore, it is not surprising that many recent FCPA investigations and settlements relate to the oil industry in Africa, Central Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East. Nigeria, the largest oil producer in Africa and the eighth-largest producer in the world, is perennially singled out as one of the world's most corrupt countries. In November 2010, seven companies operating in and around the oil and oil-services industries agreed to pay $236 million in fines and disgorgement in connection with improper payments made to government officials in Nigeria and other countries.

The firms settling comprised a global freight forwarder and six oil and oil-services companies, many of which were customers of the freight forwarder. Significantly, the investigation is directly connected to a 2007 settlement with a separate company with ties of its own to the freight forwarder.

Banking and Private Equity

The SEC reportedly is investigating a number of banks and private equity firms for possible FCPA violations in their dealings with sovereign wealth funds and foreign national pension funds. In January 2011, the SEC sent letters to 10 firms requesting information about their relationships with sovereign wealth funds, which are made up of currency reserves and invested for profit (see "SEC Probes Banks, Buyout Shops Over Dealings With Sovereign Funds," The Wall Street Journal, January 14, 2011). Sources familiar with the investigation report that the SEC is also investigating the firms' relationships with foreign national pension funds, which have invested more than $13 billion in U.S. private equity firms in the last decade (see "SEC's Sovereign Wealth Fund Probe Is More Than Name Suggests," The Wall Street Journal, February 9, 2011).

NonProsecution Agreements

In 2009, the SEC Director of Enforcement created a specialized FCPA enforcement unit and pledged to resolve investigations using public deferred-prosecution agreements, a method that the DOJ has long employed to encourage companies to come forward with evidence of misconduct. At the end of 2010, the SEC entered into its first nonprosecution agreement with a company facing allegations of fraud and insider trading.

The full impact of this new enforcement tool remains unclear. Despite the multitude of FCPA enforcement actions in 2010, the SEC chose to enter into its first nonprosecution agreement for a case where the misconduct was relatively isolated and the company promptly and completely selfreported the misconduct to the SEC. In this case, the SEC could plausibly have taken no action, as it had already initiated an enforcement action against the offending individual within the cooperating company. It is uncertain how nonprosecution agreements will be used for a company with a widespread pattern of misconduct or a company disclosing more serious misconduct.

Enforcement Outside the U.S.

While the U.S. continues to lead the anti-corruption fight, global anti-corruption enforcement continues to increase. Although delayed, the U.K. Bribery Act will likely be implemented this year, providing a powerful new enforcement tool. Other countries are also initiating enforcement actions against businesses engaged in improper behavior within their borders.

U.K. Bribery Act

On April 8, 2010, the U.K. passed the Bribery Act 2010 (UKBA). The UKBA, which has yet to be implemented, is designed to simplify and modernize the U.K.'s current patchwork of common-law and statutory offenses to prevent bribery. The UKBA increases penalties for corrupt payments that, as in the FCPA, include bribes to foreign public officials, as well as offering, promising, requesting, accepting, or agreeing to receive a bribe. The UKBA's jurisdictional reach is also similar, applying to both bribes made on U.K. soil by foreign companies and those made overseas by U.K. citizens (including businesses, passport holders, and residents).

The UKBA differs from the FCPA in two key respects:

- Corporate offense for failing to prevent bribery. The UKBA holds corporations accountable for failing to prevent bribery by persons associated with the entity that conducts any part of its business in the U.K., regardless of its corporate citizenship or where the conduct occurred. This offense is subject to strict liability but allows for a statutory defense for a corporation that can prove that it had in place "adequate procedures" designed to prevent bribery.

- No facilitating-payments exception. The UKBA contains no exception resembling the FCPA's treatment of facilitating or "grease" payments. Opponents challenged this aspect of the UKBA, arguing that it would prohibit activities permitted in jurisdictions such as the U.S., placing U.K. businesses at a commercial disadvantage. However, because the FCPA's exception for facilitating payments provides a notoriously unreliable legal standard, many U.S. companies have opted to ban these payments. The UKBA's prohibition is also in line with broader trends in anti-corruption law. For example, last year the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) called for member countries to prohibit facilitating payments altogether.

After two delays in 2010, the U.K. Ministry of Justice announced on January 31, 2011, that implementation of the UKBA would be delayed until three months after the Serious Fraud Office (SFO) had issued guidance on the meaning of adequate procedures under the statutory defense. The three-month period was designed to allow businesses time to prepare for and adapt to the new regime. The guidance is expected to clarify:

- The proper scope of adequate procedures.

- The extent to which the SFO will exercise prosecutorial discretion under the new legislation.

The delay suggests that formulating this guidance has been a complex and onerous task. It has also raised concerns that the implementation of the UKBA may be significantly delayed and that the law itself is facing additional scrutiny from the U.K. government.

Despite these delays, the UKBA is widely expected to come into force in the first half of 2011. With the UKBA, the U.K. government is likely to join the U.S. government in aggressively prosecuting extraterritorial corruption by companies doing business within its borders.

Other Overseas Enforcement

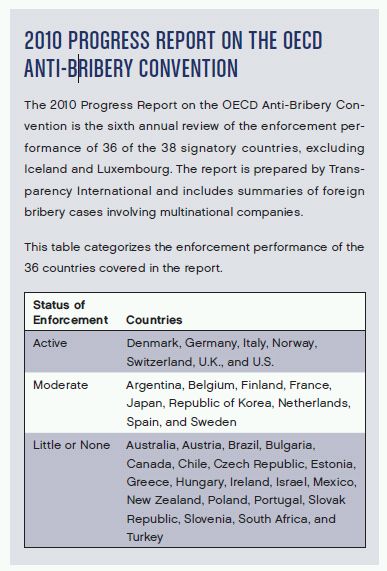

Overseas enforcement activity is being driven, in part, by the OECD Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions (OECD Anti- Bribery Convention). The OECD Anti-Bribery Convention has issued standards for anti-corruption legislation and enforcement in 38 signatory countries. In the 2010 Progress Report on the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention (2010 Report) prepared by Transparency International, seven signatory countries had active enforcement activities, an improvement over the four reported in 2009 (see box, "2010 Progress Report on the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention"). The 2010 Report, however, reveals a significant decline from 2008, when the OECD reported that 16 signatory countries had active enforcement activities.

In addition, many nonsignatory countries have increased their enforcement activities. For example, in 2010:

- Costa Rican authorities recovered $10 million from a French telecommunications firm in connection with corruption charges arising from the same bribery conduct that led to the company's $137 million settlement with the DOJ and SEC.

- Nigerian authorities recovered more than $100 million from the companies involved in the Bonny Island bribery cases.

Greater enforcement activity can also be attributed to the increased resources the U.S. government has provided for anti-corruption investigations worldwide. Not only has the U.S. bolstered the Federal Bureau of Investigation and other agencies tasked with investigating FCPA violations, it has provided forensic training and technology to other countries. In many cases, FCPA-trained attorneys have been placed in foreign embassies to assist foreign governments with ongoing investigations.

Companies should expect a growing number of countries to pursue corruption charges based on conduct occurring within their borders. This trend could lead to conflicting anticorruption standards and parallel proceedings, though that has yet to become a significant problem for international companies in this area of the law.

Enforcement Actions Against Individuals

U.S. enforcement authorities have gone beyond punishing corporations that make corrupt payments overseas and are now pursuing individual decision makers. In the past two years, more than 50 individuals have been charged with violations of the FCPA. By focusing resources on cases against individuals, the government may attract more cooperating witnesses and generate even more FCPA investigations. This is because individuals facing punishment for FCPA violations may want to assist the government in further investigation of former employers and business partners in exchange for reduced punishment.

Enforcement authorities have identified two groups of individuals to target:

- Executives who authorize corporate bribes.

- Foreign government officials who receive bribes.

The penalties imposed on individuals for FCPA violations can be severe. The consequences of prosecution may include:

- Prison sentences.

- Financial penalties.

- Legal fees.

The DOJ has imposed serious penalties for white-collar crimes, including long prison sentences (see box, "Punishments for Individuals"). Financial penalties can also be substantial, and the FCPA prohibits issuers from paying the criminal and civil fines imposed on their individual officers, directors, employees, agents, or stockholders (15 U.S.C. § 78ff(c)(3)).

This trend could have significant practical consequences. Threatened with personal exposure, corporate executives are more likely to show caution when risks arise in business deals or transactions. Accordingly, company leaders and counsel should be prepared to answer questions regarding the extent to which individual employees may be liable for corporate actions.

FCPA Compliance

Companies operating internationally should expect 2011 to bring increasing scrutiny from enforcement authorities in the U.S. and abroad. Unfortunately, companies attempting to comply with the FCPA struggle with a lack of interpretive guidance.

Therefore, companies must rely on the following for guidance:

- Deferred-prosecution agreements.

- Nonprosecution agreements.

- DOJ Opinion Procedure Releases.

Notably, the DOJ's Deputy Assistant Attorney General, Criminal Division, recently described Opinion Procedure Releases as the best source for companies with doubts about the propriety of specific transactions or business opportunities.

Punishment s for Individuals

The following are recent examples of severe punishments imposed on individuals for violations of the FCPA:

- In December 2010, a former employee of an international oil-services firm pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to violate the FCPA. The former employee faces a penalty of up to five years in prison. He also agreed to forfeit $726,885 as part of his plea agreement.

- In June 2010, a former agent in Iraq for an American specialty-chemical maker pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy and one count of violating the FCPA for his role in a scheme to pay kickbacks to the Iraqi government under the UN Oil-for-Food Programme. The former agent faces a penalty of up to 10 years in prison. He also agreed to pay the SEC more than $1.3 million in disgorgement, civil penalties, and prejudgment interest.

- In April 2010, a former officer of the Panamanian affiliate of an American engineering firm was sentenced to 87 months in prison for conspiracy to violate the FCPA and making a false statement to the FBI in connection with bribes paid to government officials in Panama. The former officer was also ordered to pay a $15,000 fine.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.