In Rigas v. United States, 2011-1 U.S.T.C 50,372 (S.D. Tex. 2011), the U.S. district court held that a partnership did not exist between an energy company (the "Company") and a limited partnership (the "Manager") that managed the Company's oil and gas properties (the "Portfolio"). Instead, the court treated the Manager as a service provider whose 20% profits interest was compensation for services taxable as ordinary income and not an allocation of income from a partnership that would have been taxable as a capital gain. The importance of this case is that the facts fit within most hedge fund and private equity structures except that in Rigas the manager did not receive the standard 2% of the annual value of the partnership assets as an annual management fee (in addition to a 20% profits interest) and, unlike most agreements, the parties in Rigas had to argue against their form—an argument the court was willing to entertain—because their agreement stated that no partnership was intended.

Background

Under a management agreement (the "Agreement") with the Company, the Manager agreed to manage and administer the Portfolio in exchange for a performance fee. The Company retained title, ownership, and control of the Portfolio. The Manager could not sign binding commitments to sell any asset in the Portfolio, incur unforeseen expenses or enter into transactions that were not previously approved by the Company. The Agreement expressly stated that the parties did not intend to create a partnership and that the Manager is an independent contractor that would receive a performance fee as compensation for services.

The Manager borrowed funds from the Company to cover its overhead expenses, such as the salaries of its individual partners (of which the taxpayer was one of five partners) in exchange for a nonrecourse promissory note (the "Note"). Under the Agreement, the Manager's performance fee is equal to 20% of the profits derived from the Portfolio based on the following priority of payments: First, the Company would recoup all third party out-of-pocket expenses. Second, the Company would recoup the initial value of the Portfolio. Third, the Company would receive a preferred return of 10% of the profits. Fourth, the Company would be repaid any amount outstanding under the Note. Fifth, the Company and the Manager would split the residual profits, 80% and 20%, respectively; however, the Manager's performance fee (i.e., 20% profits interest) is subject to "clawback" to ensure that the Company receives the amounts provided for in steps one through four above.

Consistent with the statements in the Agreement, the Company and the Manager did not file a partnership tax return reflecting a joint venture between them and did not report their respective profit share on Schedules K-1. During the tax year at issue, the capital assets in the Portfolio were sold at a gain and, pursuant to the above schedule, the Manager received approximately $20 million as its performance fee, of which $31,920 was paid back to the Company under the clawback provision. The taxpayer argued that, because the Manager is a partner with the Company in a joint venture, the performance fee received by the Manager is subject to tax as a long term capital gain.

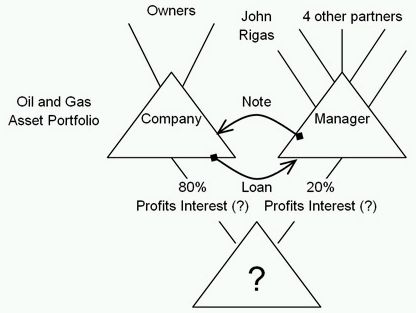

The key facts of the case are summarized in the following structure chart:

Priority of Payments:

|

Relevant Factors for Identifying Partnership

The court relied on the following factors set forth in Luna v. Comm'r, 42 T.C. 1067 (1964) to determine whether the parties intended to form a partnership:

Agreement of the Parties

In the Agreement, the Company and the Manager expressed their intent not to form a partnership and instead characterized the Manager as an independent contractor whose performance fee is compensation for services. Despite this statement, the court emphasized that the Agreement is not dispositive and, based on the parties' conduct, a partnership may exist.

Contributions of the Parties to the Venture

The court acknowledged that it is possible to treat the Manager as having made a partnership capital contribution in the form of services and a deferred capital contribution in the form of reduced performance fees to account for repayments under the Note.

Interest in Profits and Losses

Sharing in profits, losses, or both is a key factor for identifying a partnership. Even though the Manager was entitled to 20% of the profits, the court found that the Manager would in all events be paid for its services—either a performance fee based on profits if the Portfolio performed well or salaries under the Note if the Portfolio performed poorly. (If the Portfolio was profitable, the Manager would have received its profit share but would have had to repay the salary received under the Note whereas, if the Portfolio was unprofitable, the Manager would not receive any profits and would not have to repay the amounts borrowed under the Note because it was nonrecourse to the Manager.) Thus, unlike a partner who contributes know-how to a partnership and receives a separate salary for services plus a profits interest if the partnership performs well, the Manager would earn only one form of compensation for its services regardless whether the partnership was profitable or not. Moreover, the fact that compensation is measured by reference to profits derived from the sale of property does not automatically convert the relationship to a partnership because a fee based on profits can be characterized as contingent compensation which is an arrangement common for brokers. In terms of losses, the court acknowledged that the clawback indicates loss sharing because the Manager would have to, and did in fact, pay back some of its performance fee to allow the Company to recover its expenses and initial investment if expenses exceeded the profits distributed. Nevertheless, it is equally consistent to view the performance fee and clawback as part of a formula designed to determine the amount of contingent compensation to be paid to the Manager as a service provider. Moreover, the nonrecourse nature of the Note, which was unsupported by any collateral, is designed to ensure that the Manager would not bear the losses of the Company if the Portfolio performed poorly, unlike the losses a typical partner might bear as a member of a partnership.

Parties' Responsibilities and Right To, and Control Over, Income and Capital

The Manager did not hold title to the Portfolio and had no practical ability to control the Portfolio or any business income. The Agreement limited the Manager's ability to exercise authority over key matters affecting the Portfolio such as buying and selling assets, entering into contracts, or drawing on the Company's bank accounts. Thus, the court appreciated the difference between a manager giving advice about the Portfolio and a partner controlling significant decisions affecting the assets in the Portfolio.

Representations to IRS and Third Parties

The Company and the Manager did not file a partnership tax return for an entity, a joint tax return or joint financial reports but instead maintained separate accounting and financial arrangements.

On balance, the court found that while a couple of factors were in the taxpayer's favor (i.e., the Manager contributed services and capital and the Manager shared in losses through the clawback), the remaining factors all point to a service relationship (i.e., the performance fee was the only source of income that the Manager received for services, the Manager may be viewed as not bearing losses because the Manager would not have to pay back amounts due under the Note, the performance fee functions in the same way as contingent compensation, the Manager lacked the authority to make significant business decisions affecting the Portfolio, and the parties did not represent to the IRS or third parties that a partnership existed consistent with the Agreement's disclaimer of a partnership arrangement). Because on balance the factors weighed heavily in favor of a service provider relationship between the Manager and the Company, the performance fee was subject to tax as ordinary income.

Observations

This case illustrates a back-to-basics approach in evaluating whether a real partnership exists. The lesson learned is that issuing a manager a "profits interest" (sometimes called a "carried interest") will not necessarily be treated as an interest in the future profits of a partnership if the manager is more properly viewed as a service provider and not a partner for U.S. tax purposes. A profits interest in an investment partnership is typically given to management as a way for the partnership to obtain the future services of an individual without the individual having to contribute capital to the entity. The profits interest is not taxable on the date of grant but still participates in the future appreciation of the business (which in turn is dependent in large part on the skill of the manager himself). Thus, the profits interest is considered to start with a zero dollar value and grow in value as the partnership's value increases. The benefit to the manager of receiving a profits interest is that income from a profits interest is taxed to the partner based on the character of the income at the partnership level, namely, at ordinary income rates or capital gains rates depending on the source of the underlying investment. (Typically, the sale of an investment business will create mostly capital gain).

Rigas brings to the forefront the fundamental question of the relationship between a manager and an investment fund. In this case, the Agreement states unequivocally that no partnership arrangement is intended. Generally, taxpayers are bound by the form of their transaction and precluded from arguing substance over form principles. Otherwise, both parties to a transaction could enjoy tax benefits based on inconsistent reporting of the same transaction. Here, however, the court did not treat the Agreement's language as dispositive and looked to factors beyond the terms of the Agreement, namely, contributions, control, and sharing of profits and losses, to ascertain the parties' true intent. Typically, sharing in profits and losses is a hallmark of a partnership arrangement and, as the court acknowledged in Rigas, the performance fee and the clawback are indicative of a partnership (although, admittedly, the Manager would only share in losses if the Portfolio was profitable). Despite these characteristics of profit and loss sharing, the court found that it is equally consistent to treat the performance fee and clawback as a form of contingent compensation especially as the performance fee was the only source of income that the Manager would receive for services rendered.

The take away from Rigas is that a net profits interest will not, in and of itself, create a partnership. In negotiating agreements with investment funds, managers who wish to be taxed as partners in the fund should consider receiving more than one source of income that includes a management fee as compensation for services rendered and a performance fee based on profits. In addition, managers should have true loss sharing by having some amount at risk in the deal, such as making the Note a recourse obligation instead of nonrecourse. These factors when combined with a clear intent to be a partner, including joint participation in the management and control of the venture (including over key areas affecting the fund's income and assets), and holding oneself out as a partner, should weigh favorably toward partnership characterization.

IRS Circular 230

For purposes of complying with IRS Circular 230 Standards of Practice, we advise you that any U.S. federal tax advice contained herein is not written to be used for, and the recipient and any subsequent reader cannot use such advice for, the purpose of avoiding any penalties asserted under the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.