In the wake of the dramatic changes to the federal gift and estate tax laws brought about by the enactment of the Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization and Job Creation Act of 2010 (the "2010 Tax Relief Act"; P.L. 111-312) at the end of 2010, 2011 was relatively quiet. It brought few statutory changes on the charitable giving front, aside from the expiration of certain tax provisions noted below. Nevertheless, new case law, Internal Revenue Service rulings and economic trends have provided more than a few topics for discussion in this update. Meanwhile, with the 2010 legislation set to expire at the end of 2012, we anticipate more excitement on the horizon.

Expiration of Tax Laws Relating to Charitable Gifts

The following charitable giving incentives, which had most recently been extended by the 2010 Tax Relief Act, expired on December 31, 2011:

- Tax-free distributions from IRAs for charitable purposes

- Favorable basis adjustment to stock of S corporations making charitable contributions of property

- Increased contribution limitations and carryover periods for charitable contributions of qualified conservation property

- Enhanced charitable deductions for contributions of food inventory, book inventories to public schools, and corporate contributions of computer equipment

It is currently unclear whether Congress will act this year to retroactively extend or make permanent any of the above provisions.

Also as a result of the 2010 Tax Relief Act, the Pease limitation on itemized deductions, which effectively reduces by 3% a taxpayer's total itemized deductions to the extent that his or her adjusted gross income exceeds a designated level, is ineffective for 2012. The Pease limitation is set to return in 2013.

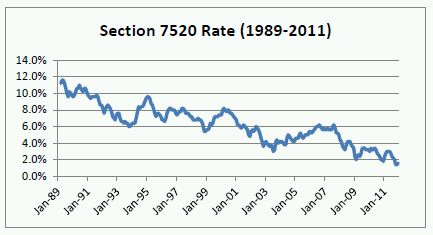

Historically-Low Interest Rates Impact Planned Giving Options

Market interest rates have dropped significantly since 2007 and are currently hovering at historic lows. This reduction in rates has led to a corresponding reduction in the Section 7520 Rate ("7520 Rate"), which is used to value the charitable and non-charitable interests created by certain planned giving arrangements, such as charitable lead trusts, charitable remainder trusts, charitable gift annuities and gifts of a remainder interest in real estate. The 7520 Rate for both February and March 2012 is 1.4%. A low 7520 Rate makes some planned giving structures more advantageous, and makes others less attractive or even unavailable to some donors.

Charitable Lead Annuity Trusts (CLATs): A low 7520 Rate makes CLATs particularly attractive to donors. The value of the charitable interest, and the corresponding income, gift or estate tax deduction for the donor, is equal to the present value of the annuity stream the charity expects to receive. This value, and hence the donor's charitable deduction, increases as the 7520 Rate decreases. The other impact of a decreasing 7520 Rate is that the value of the non-charitable interest decreases. Therefore, if the donor provides that the non-charitable interest will benefit someone other than herself, the value of the donor's gift for gift tax purposes would be lower in a low-interest rate environment, potentially resulting in gift tax savings for the donor.

To illustrate these points, consider a donor who funds a $1,000,000 10-year CLAT providing for a 10% payout to charity with the remainder payable to the donor's children at the end of the term. If the CLAT's investments earn 6% annually over its 10-year term, the following table depicts the results based on the 7520 Rate in effect at the time of contribution:

|

7520 Rate |

2% |

4% |

6% |

|

Tax Deduction |

$898,300 |

$811,000 |

$736,000 |

|

Amount of Taxable Gift |

$101,700 |

$189,000 |

$264,000 |

|

Amount Passing to Charity |

$1,000,000 |

$1,000,000 |

$1,000,000 |

|

Amount Passing to Children |

$472,800 |

$472,800 |

$472,800 |

Although in each of the above examples the charity and the children receive consistent amounts from the trust, in the lowest interest rate environment the donor will obtain the largest gift tax charitable deduction and thus can transfer property to her children at the lowest gift tax cost.

Charitable Remainder Annuity Trusts (CRATs): Conversely, a lower 7520 Rate will result in a smaller income tax charitable deduction for a donor who establishes a CRAT. More importantly, CRATs have been significantly impaired by low 7520 Rates because of the "5% exhaustion test." This test provides that there must be a 5% or lower probability that the CRAT's assets are exhausted before a distribution is made to charity at the end of the term. For purposes of this test, the 7520 Rate is the CRAT's assumed annual investment return over its term. Accordingly, if the 7520 Rate is below the CRAT's annuity rate, which must at a minimum be 5% of the initial value of the trust regardless of market conditions, this results in some possibility of exhaustion. If the difference between the two rates is small, the CRAT may still be able to pass the 5% exhaustion test. However, at the 7520 Rate's current level, which is well below the CRAT's minimum 5% annuity rate, this test is difficult to pass. Thus, only a CRAT with a short term will satisfy the test. For example, if the 7520 Rate is 2%, a 5% CRAT cannot be designed to make annuity payments for the lifetime of any person who is younger than 72 years old. Likewise, a 7% CRAT cannot be designed to make annuity payments for the lifetime of any person who is younger than 82 years old.

Charitable Gift Annuities (CGA): All other factors being equal, a low 7520 Rate will reduce the actuarial value of the charitable gift associated with a CGA, as well as the corresponding income tax charitable deduction available to the donor. Because charitable organizations set their CGA annuity rates based on prevailing market interest rates, a CGA purchased when interest rates, and hence the 7520 Rate, are low will also generally pay a lower annuity rate than one purchased when rates are higher. (See the discussion below regarding the ACGA's downward adjustment to its recommended annuity rates.) The silver lining is that the donor's contribution for the annuity contract is higher relative to what the annuitant receives, thereby increasing the investment in the contract and reducing the income tax liability associated with the annuity payments.

Gifts of a Remainder Interest in Personal Residence: While the real economic benefit to the donor—the right to live in and enjoy the property for his or her lifetime—is constant regardless of the 7520 Rate, gifts of a remainder interest in a personal residence are more advantageous when the 7520 Rate is low, since that rate serves as the discount rate in determining the present value of the donor's retained life estate in the property. The corresponding valuation of the remainder interest in the residence increases as the 7520 Rate decreases, as does the associated gift tax charitable deduction available to the donor. The income tax deduction for the transfer of the remainder interest in the residence to charity is based on a more complex formula that takes into account straight-line depreciation on a portion of the subject property and effectively reduces the value of the income tax deduction as compared with the gift tax deduction. Even so, in the context of a gift of a remainder interest in a personal residence to charity, a lower 7520 Rate will still produce better income tax results for the donor than a higher rate would.

Charitable Remainder Unitrusts (CRUTs) and Charitable Lead Unitrusts (CLUTs): CRUTs and CLUTs make a unitrust payment that fluctuates annually based on the market value of the trust, as opposed to a fixed annuity payment. The measurement of the charitable and non-charitable interests in CRUTs and CLUTs is driven by the unitrust percentage stated in the trust rather than the 7520 Rate, making CRUTs and CLUTs far less sensitive to interest rate changes than their annuity trust counterparts. Because it is used to determine the adjustment factor in connection with the trust's payout frequency, the 7520 Rate affects the measurement of the unitrust interest only in the first year of the trust term. Accordingly, the low-7520 Rate environment has little or no impact on the analysis of these techniques.

New ACGA Suggested Maximum Gift Annuity Rates

The American Council on Gift Annuities ("ACGA") approved a new schedule of suggested maximum gift annuity rates effective January 1, 2012. The new rates reflect significant changes in the economic environment, including a reduction in the underlying gross annual investment return assumption from 5.0% to 4.25%. The rates retain the ACGA's targets of a 50% remainder and a 20% present value of such remainder at the time of contribution, the latter requirement having been first applied with respect to the July 2011 rate schedules. (Note that the ACGA's 50% remainder measure far exceeds the requirement of § 514(c)(5) of the Internal Revenue Code (the "Code") that a gift annuity have a minimum remainder value of 10% of the value of the contributed property to avoid generating unrelated business taxable income to the charity.)

Tax Filings and Disclosure of Split-Interest Trust Information

In 2011, the IRS began to include certain information about split-interest trusts derived from Form 5227, including the trust's name, employer identification number, address and value, in the IRS's EO Business Master File extract, which is publicly available via the IRS's website. Other organizations, including GuideStar, have picked up this data and made it available on their own websites. The schedule to Form 5227 on which donor and beneficiary information is reported is not available to the public and was not included in the EO Business Master File data released by the IRS. In the numerous instances in which the donor's or beneficiary's name is included in the trust title, however, the donor's or beneficiary's identity is nevertheless easy to decipher, raising privacy concerns. It is likely that the IRS's release of split-interest trust information as part of the EO Business Master File extract last year was not an intentional shift in approach, but rather the result of a technical adjustment that was independent of and uninformed by previous informal guidance from the IRS indicating that it would not release such data unless it received a specific request for a particular trust's information. We are working with the IRS to address these continuing concerns regarding disclosure of information about split-interest trusts.

Separately, the IRS has revised the instructions to Form 990 to clarify that an exempt organization need not list the names of its related split-interest charitable trusts on Schedule R. Instead, the organization can simply report the number of each type of split-interest charitable trust (e.g. charitable remainder trust, charitable lead trust, pooled income fund), alleviating donor and beneficiary privacy concerns similar to those described above.

Charitable Remainder Trust News

There were a few interesting developments in the arena of charitable remainder trusts in 2011:

- One private letter ruling sanctions a CRAT trustee's authority to purchase a commercial annuity to satisfy its initial payout obligations. Priv. Ltr. Rul. 201126007 (July 1, 2011). Although the IRS concludes in the ruling that inclusion of such a trustee power will not disqualify the CRAT under § 664(d)(1) of the Code, it does not explore the practical difficulties that may arise if a fiduciary were to exercise the power, including the effect on the overall return of the trust investments and the manner in which the annuity income would be accounted for in the CRAT's income tiers.

- The IRS also blessed a testamentary CRT for the benefit of decedent's spouse that permitted the trustee discretion to make distributions to the surviving spouse or charity (with safeguards to ensure the non-charitable portion was not de minimis and, if the spouse remarried, with a cap on the amount permissible to the spouse). The Service determined that inclusion of such trustee discretion would not disqualify the CRT. In addition, because the spouse was the only non-charitable beneficiary of the CRT, the IRS allowed the estate tax marital deduction under § 2056 of the Code for the entire unitrust interest, notwithstanding that the spouse might receive only a portion of it. Priv. Ltr. Rul. 201117005 (Apr. 29, 2011).

- In the reformation area, we saw some private rulings allowing reformation of a CRT due to scrivener's error, Priv. Ltr. Rul. 201133004 (Aug. 19, 2011) (from NIMCRUT to CRUT), Priv. Ltr. Rul. 201113040 (Aug. 19, 2011) (from NIMCRUT to FLIPCRUT), and to restructure testamentary gifts that otherwise would not qualify for charitable deductions, Priv. Ltr. Ruls. 201125007 (June 24, 2011) and 201115003 (Apr. 15, 2011). It is no surprise that in each case proper reformation procedures were closely followed.

- In addition, more educational institutions received confirmation that investing their CRTs in their endowments would not generate unrelated business taxable income. Priv. Ltr. Ruls. 201105049 (Feb. 2, 2011), 201105050 (Feb. 2, 2011), 201123042 (June 10, 2011), 201123043 (June 10, 2011), 201123044 (June 10, 2011). Several of these rulings, as well as a few rulings published in early 2012 (Priv. Ltr. Ruls. 201208038 (Feb. 24, 2012), 201209014 (Mar. 2, 2012)), involve CRTs where the charity serving as trustee of the CRT and investing the trust assets in units of its endowment is not the exclusive remainder beneficiary of the trust. Although earlier endowment rulings were premised on the trustee charity being the sole remainder beneficiary of the trust, recently the IRS seems to have taken a more expansive view of this issue, so long as the trustee charity has a significant interest in the CRT and is not charging a fee for its services. As a reminder, private rulings cannot be relied on as precedent; we encourage any institution wishing to invest charitable remainder trusts in its endowment to seek an individual ruling on the matter.

- Finally, in Rev. Proc. 2011-41, 2011-35 I.R.B. 188, the IRS issued helpful guidance for personal representatives of 2010 decedents, confirming that a testamentary CRT otherwise meeting the requirements of § 664 of the Code but failing to meet the requirement that an estate tax deduction is allowable under § 2055 only because the estate opted out of the federal estate tax under § 1022 will nonetheless qualify as a valid CRT under § 664.

Conservation Easement Developments

In several cases decided in 2011, the courts denied the charitable deduction where the taxpayer failed to meet the requirements of a qualified conservation contribution and/or failed to meet the associated substantiation requirements. These cases highlight the importance of strictly adhering to qualified conservation contribution requirements under § 170(h) of the Code and the substantiation requirements under § 170(f)(8) of the Code where a donor wishes to contribute a conservation easement to a qualified charity.

In Didonato v. Comm'r, T.C.M. 2011-153 (2011), the Court held that the taxpayer and the county's agreement regarding the taxpayer's donation of his developments rights to the county failed the contemporaneous written acknowledgment requirement where the obligation to transfer the rights would not mature until the county obtained state approval for the disposition, which occurred 15 months after the contribution. In Schrimsher v. Comm'r, T.C.M. 2011-071 (2011), the Tax Court held that the charity's written acknowledgement was insufficient because it did not specifically state that the charity received no consideration for the contribution. Finally, the Tax Court denied a taxpayer the charitable deduction for the donation of a façade easement because the appraisal attached to the Form 8283 was not a "qualified appraisal." The appraisal in question did not include the method and specific basis for valuing the easement and development rights. See Friedberg v. Comm'r, T.C.M. 2011-238 (2011).

Perhaps surprisingly, in Comm'r v. Simmons, 646 F.3d 6 (D.C. Cir. 2011), the D.C. Circuit affirmed the Tax Court's decision that the contribution of a façade easement was deemed exclusively for conservation purposes even though the charity could consent to changes in the façade of the building and/or abandon its rights to enforce the easement. But see Carpenter v. Comm'r, T.C.M. 2012-1 (2012) (denying taxpayers a charitable deduction for their conveyance of a conservation easement on the basis that such contribution was not "in perpetuity" where the taxpayers and the charity retained the right to extinguish the conservation easement through mutual agreement of the parties).

The IRS also updated its Conservation Easement Audit Techniques Guide in September 2011 and again in January 2012. Internal Revenue Service Conservation Easement Audit Techniques Guide (2012). In addition to providing guidance for IRS examiners, the Guide is a must-read for donors and advisors structuring conservation easement gifts. The IRS has made corresponding changes to the instructions for Schedule D to Form 990, emphasizing in the instructions, for example, that conservation easements must be granted and protected in perpetuity.

Charitable Defined Value Clauses

Some estate planners have counseled clients about a gift-planning strategy involving gifts of closely-held or hard-to-value assets to a group consisting of family members and one or more charities. The allocation of the assets among the non-charitable and charitable beneficiaries of the gift turns on a formula that is based on the value of the assets, as finally determined for federal gift tax purposes. If the property provisionally allocated to the non-charitable beneficiaries is found to exceed a designated value, which is usually keyed to the donor's remaining gift tax exemption, the excess property will be reallocated automatically under the terms of the gift agreement to the charitable beneficiaries, thereby preventing any gift tax liability for the donor. These gift agreement provisions, sometimes called defined value clauses, are typically used in situations where the donor

intends to discount the value of the contributed property for gift tax purposes because it is unmarketable or it comprises a minority interest, and the donor anticipates that the IRS may challenge the valuation. The IRS has argued that such defined value clauses prevent the charitable portion of the gift from qualifying for the gift tax charitable deduction because the transfer to charity is conditioned on the results of a gift tax audit. In addition, the IRS has argued that, because there is no incentive on the Service's part to bring audits that do not generate additional revenue for the government, the clauses are against public policy. In two cases decided in 2011, however, the courts upheld defined value clauses involving gifts to charitable organizations.

In Hendrix v. Comm'r, T.C.M. 2011-133 (2011), the Tax Court found that the defined value clause in question was reached at arm's length and was not void as a matter of public policy. The Court found it significant that the donor advised fund named as the beneficiary under the gift agreement participated in negotiating the terms of the gift agreement, was represented by separate counsel and engaged an independent appraiser to review the appraisal commissioned by the donors to determine the initial allocation of the closely-held stock that was the subject of the agreement. The charity also had a fiduciary obligation under federal and state law to ensure that it received what it was due under the agreement. In addition to finding that the gift agreement was reached at arm's length, the Court found that it was not in violation of public policy because it did not in any way defeat the original transfer of the property and, in fact, it promoted the public policy of encouraging gifts to charity.

In Estate of Petter v. Comm'r, 653 F.3d 1012 (9th Cir. 2011), the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit declined to address the IRS's public policy arguments but rejected the IRS's technical arguments in connection with the charitable gift of LLC units that arose from the operation of a defined value clause. The Court found that the transfer of property to the charity was complete as of the date of the gift agreement, when the charity's rights first arose, and was not contingent on the occurrence of a later gift tax audit. Adjustments under the defined value clause represented the enforcement of the charity's contractual rights under the agreement rather than additional transfers.

The Hendrix case, in particular, highlights the importance of the charity's participation in defined value clause planning. If a charity is approached by donors interested in including them in a defined value clause gift agreement, it should engage its own lawyer to review the agreement and negotiate the terms on the charity's behalf. In addition, the charity should pay careful attention to the valuation of the contributed property, at a minimum hiring a qualified advisor to independently review the appraisal. No matter how significant the potential gift or how important the donor to the charity, the charity must do its due diligence with respect to the defined value clause arrangement. In the end, the charity's vigilance may contribute as much to the success of the donor's gift planning as it does to the protection of the charity's interests.

Noteworthy State Law Developments

Courts in Massachusetts and New York addressed the issue of a charity's standing to participate in court proceedings. The Massachusetts Appeals Court found that a charitable organization to which a donor directed his investment advisor to transfer stock had standing to sue the advisor for breach of contract when the gift was delayed and the stock declined in value. The Court found that the charity was the intended third-party beneficiary of the contract between the donor and the investment advisor as it applied to the gift and thus could bring its claim, although the Court expressly declined to address whether a breach of contract in fact occurred. James Family Charitable Found. v. State St. Bank & Trust Co., 80 Mass. App. Ct. 720 (2011).

In two other cases involving standing, the Massachusetts Appeals Court and the New York Surrogate's Court highlighted the limitations on a charity's ability to participate in a cy pres proceeding. The Massachusetts Court affirmed that the Roman Catholic Bishop of Springfield (RCB) could not intervene in a cy pres proceeding to expand the terms of a scholarship for boys of two Roman Catholic parishes to study forestry at specified schools, because the RCB was not itself a legal beneficiary of the trust. Hoffman v. Univ. of Mass. Amherst, 2011 Mass. App. Unpub. LEXIS 731 (June 2, 2011). Meanwhile, the New York Surrogate's Court found that a hospital that had assumed the responsibilities of the now-defunct hospital named as the beneficiary of a trust had a special and substantial interest in the trust funds and could intervene in (but could not initiate) a cy pres proceeding. In re Trustco Bank New York, as Tr. of the Kenneth T. Lally Revocable Trust, 33 Misc. 3d 745 (2011).

In a separate New York Surrogate's Court opinion, a testamentary distribution to create a private foundation was modified under the doctrine of cy pres because the $200,000 sum designated to fund it was deemed to be inadequate. Finding that "the expense of administering the independent foundation would significantly reduce the funds available for scholarships, thereby frustrating the intent of the grantors," the Court permitted the trustee to create a donor advised fund account to provide scholarships under terms similar to those in the original trust instrument. In re Dr. Robert von Tauber & Olga von Tauber, M.D. Revocable Trust Dated October 28, 1993, 33 Misc. 3d 1224A (2011).

The New York Surrogate's Court objected on state law grounds to the investment of an exclusively charitable trust in the beneficiary University's long-term investment pool, which included as investors various charitable remainder trusts, other exclusively charitable trusts and the University's endowment and was managed in a highly diversified portfolio with 85 managers. The Court found that the delegation of investment authority by the Investment Advisory Committee created under the trust instrument was inconsistent with the settlor's intent, because it effectively removed the trustee and the Committee from having any role in administering the trust and put those decisions in the hands of the University. In addition, the Court found potential conflicts of interest where members of the Committee were also employees of the University. Finally, the Court found that the proposed investment in the commingled fund would run afoul of the Prudent Investor Act, because the delegation of investment authority by the Committee was too broad. In re Trust Under Agreement of Helen Rivas, 30 Misc. 3d 1207A (2011).

The Court of Appeal of California addressed statute of limitations and pre-judgment interest issues in a case regarding a CRAT. Highlighting the importance of diversification, the trial court had earlier found that the trustee, who invested a significant portion of the trust assets in a private loan arrangement, had breached his fiduciary duty by failing to adequately diversify the trust assets in accordance with the Prudent Investor Act, ultimately depleting the trust assets and nearly exhausting the trust. Museum Assocs. v. Schiff, 2011 Cal. App. Unpub. LEXIS 1752 (Mar. 10, 2011).

An ethics opinion issued by the State Bar of Nevada explored the conflict of interest that may arise when an estate planning lawyer serves on a charity's board of directors and at the same time advises an individual client regarding gifts to that charity. The reviewing committee concluded that a lawyer's fiduciary duties to the charity and his or her access to information about the charitable organization's financial situation and goals could color his or her advice to the individual client. When such a conflict arises, the lawyer can continue to serve in both roles, as long as the potential conflict is disclosed to the charity and the client and both parties consent to the representation. State Bar of Nev., Standing Comm. on Ethics & Prof'l Responsibility, Formal Op. 47 (2011).

Finally, a bill currently under consideration in the Massachusetts House of Representatives (H.3516) would prohibit any Massachusetts-based public charity or private foundation from compensating an independent officer, director or trustee (i.e. an officer, director or trustee who is not an employee of the charity) unless it obtains approval from the Director of the Attorney General's Nonprofit Organizations/Public Charities Division. The bill authorizes the Director of the Nonprofit Organizations/Public Charities Division to develop filing requirements and guidelines for the compensation approval process and suggests that an organization would need to provide a clear and convincing argument that paying compensation is necessary to enable the charity to attract and retain experienced and competent individuals to serve on its board. The bill also grants the Attorney General's Office the authority to rescind an approval, at any time, upon a finding that the amount of compensation paid is more than reasonably necessary. The effective date of the legislation would be six months after the date of enactment.

Legislative Proposals to Limit the Income Tax Charitable Deduction

Limiting the income tax charitable deduction continues to be discussed as federal officials consider possible revisions to the federal tax code. President Obama re-introduced his plan to cap the tax rate against which the deduction can be applied at 28% for high-income taxpayers in the American Jobs Act in September 2011 and has again proposed it as part of his budget for fiscal year 2013. In Fall 2011, the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction (the "super committee") also discussed several ways of limiting the deduction, including capping the tax rate against which itemized deductions can be applied.

In a similar vein, New York now limits the itemized deduction for a charitable contribution by an individual with an adjusted gross income over $10,000,000 to 25% of the contribution amount. This limitation went into effect for the tax year 2010 and remains in effect through 2012.

New Edition of the Ropes & Gray Manual

"Tax Aspects of Charitable Giving," the plain brown wrapper version of the Harvard Manual of the same name, will appear in 2012 – maybe by this summer. This is the third edition and has been written by Martin Hall and Carolyn M. Osteen of Ropes & Gray LLP. Although this Manual is directed primarily to an audience of practicing attorneys, accountants, and other professional tax counsel, it has proved to be useful to individuals who are philanthropic and/or have some familiarity with the tax law relating to charitable contributions. The new edition represents a substantial update of all federal tax rules in this area and includes new chapters relating to private foundations, donor advised funds and supporting organizations. For information about obtaining this manual, please email carolyn.osteen@ropesgray.com.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.