Have one or several playa lakes on or near a well pad in the Permian Basin? An access road nearby an ephemeral tributary of the Green River in the Uintah Basin? A pipeline that traverses lands dotted with prairie potholes in the vicinity of Williston? Effective August 28, a new definition of "waters of the United States" that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Army Corps of Engineers recently promulgated is likely to change the way oil and gas operators locate, design, construct, and maintain oil and natural gas production facilities under all these circumstances.

The agencies' redefinition of "waters of the United States" is the latest attempt to resolve a legal dispute over the scope of federal regulatory power under the Clean Water Act dating back more than three decades. In 1972, Congress passed the Clean Water Act "to restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the Nation's waters." Among other provisions, the Act prohibits the discharge of "any pollutant to navigable waters from any point source."1 But while the Clean Water Act defines "navigable waters" as "waters of the United States,"2 the Act omits any definition of "waters of the United States."

Since at least the late 1970s, EPA (the agency with primary enforcement authority under the Clean Water Act) and the Corps of Engineers (the agency that administers the "Section 404" permitting program regulating the discharge of dredged or fill material into waters of the United States) have attempted to fill this statutory gap through regulations. From the start, those regulations have been controversial, with opponents contending that the regulatory definition of "waters of the United States" represented an attempt to assert jurisdiction over a broader suite of waters than the Clean Water Act contemplates and waters beyond Congress's power to regulate under the Constitution's Commerce Clause. Legal battles over the meaning of "waters of the United States" have proliferated in federal courts across the country, reaching the Supreme Court at least three times. Yet none of this litigation has provided any clarity. The last case to reach the Supreme Court, Rapanos v. United States in 2006,3 resulted in five disparate judicial opinions, none of which commanded a majority opinion of the Court.

Beyond the legal acrobatics, the failure to provide an enforceable and consistent definition of "waters of the United States" has real consequences for the regulated community. Without a collective sense of where such waters are, Clean Water Act enforcement has been an exercise in inconsistency subject to the individual whims of local field officers. For energy companies, this variability adds uncertainty to important aspects of planning and development. The concept of "navigable waters," and therefore "waters of the United States," is incorporated into a number of programs under the Clean Water Act, among others: (i) the section 402 National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System permit program; (ii) the section 404 permit program associated with placement of dredged or fill material; (iii) the section 311 oil spill prevention and response program; (iv) the water quality standards and total maximum daily load programs under section 303; and (v) the section 401 state water quality certification process.4

On June 29, 2015, EPA and the Corps of Engineers issued a final rule that the agencies contend is crafted to eliminate this uncertainty. The agencies contend that the new "rule makes the process of identifying waters protected under the [Clean Water Act] easier to understand, more predictable, and consistent with the law and peer-reviewed science, while protecting the streams and wetlands that form the foundation of our nation's water resources."5 Not surprising, the final rule is already the subject of litigation in courts around the country. Whether those legal challenges will ultimately be successful and, if not, whether the final rule will prove more predictable in practice remains to be seen. In the interim, oil and gas operators struggle to determine how the new rule will affect their operations. As operators undertake that effort, four key factors should inform their analysis.

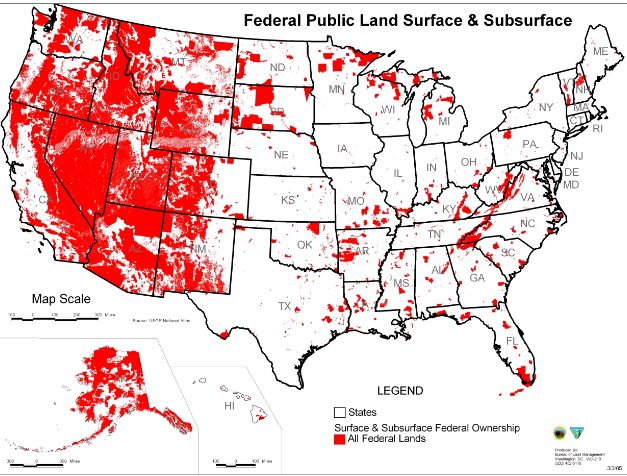

1. The Rule Applies Everywhere.

The federal government controls more than 700 million acres of mineral estate across the United States, approximately one-third of the country, and is the custodian over approximately 56 million additional acres of Indian mineral estate.

Many federal regulatory initiatives focus on activities on these lands. The Bureau of Land Management's recently finalized hydraulic fracturing rule, for example, governs the use of hydraulic fracturing on the federal and Indian lands only. But the scope of the "waters of the United States" definition is not so limited. More akin to the manner in which the Endangered Species Act is enforced, the "waters of the United States" definition applies to all operations, everywhere, irrespective of the ownership status of the surface. That means operators are required to ensure compliance with the regulatory provisions on every operation throughout the United States. Every well pad, access route, pipeline right-of-way, and ancillary production facility is subject to the final rule.

2. "Waters of the United States" Does Not Require Water.

Perhaps the most controversial feature of how the federal agencies have historically applied the "waters of the United States" rule is that the presence of actual water has never been a prerequisite for a site to be designated as jurisdictional. The agencies' definition encompasses "wetlands" that are rarely wet, flood plains that rarely flood, ephemeral tributaries that respond only to extreme precipitation events, and other features that do not correspond to the common or ordinary understanding of "water."

According to the EPA and the Corps of Engineers, some "waters of the United States" look like this:

An interagency team performs a jurisdictional delineation of an alleged wetland on a proposed well pad in Utah.

Given the agencies' expansive understanding of what constitutes a water feature, operators must consider potential Clean Water Act implications no matter where operations are located or planned, even where the presence of water is neither regular nor obvious.

3. The New Rule Is Already Functionally Effective.

The new rule is officially effective on August 28, 2015. But EPA and the Corps of Engineers caution that jurisdictional determinations are "governed by the rule in effect at the time the agency issues a jurisdictional determination or permit authorization, not by the date of a permit application, request for authorization, or request for a jurisdictional delineation."6 Given the backlog of permit and jurisdictional delineation requests, the agencies caution that "requesters seeking jurisdictional determinations after the rule is published [June 29, 2015] should expect the determination will be made consistent with this rule."7

Perhaps more critical, the new rule also applies to sites for which a jurisdictional determination has already been conducted. Approved jurisdictional determinations are generally valid for five years. And while the agencies indicate that approved determinations will not be re-opened – and will therefore remain valid until expiration – when the jurisdictional determination for a site expires and the site is re-evaluated for renewal, the subsequent evaluation will be conducted under the new rule. The sum of that process is that, within five years of August 28, 2015, every single component of every oil and gas operator's production and operational facilities will be subject to re-evaluation under the new rule.

4. More Sites Will Be Categorically Jurisdictional.

Although the agencies suggest that the new rule is designed to make jurisdictional determinations "consistent with the law and peer-reviewed science,"8 the agencies concede that the designation of a site as a jurisdictional water is "not a purely scientific determination."9 To achieve the goal of having a more predictable regulatory scheme, the agencies' final rule provides for several categories of sites that, under existing regulations, would have been subject to a scientific jurisdictional evaluation but which will now be deemed jurisdictional per se.

Certain categories of jurisdictional waters remain unchanged: traditionally navigable waters, interstate waters, the territorial seas, and impoundments of jurisdictional waters all remain jurisdictional per se. But other categories have expanded. While existing regulations have always classified "tributaries" to the four aforementioned categories as jurisdictional, the new rule provides that, so long as a water feature has both a bed and banks and a definable ordinary high water mark, that feature is per se jurisdictional even if it does not contribute water to a downstream jurisdictional water directly and even if its flow is less than perennial. Under the new regulatory framework, tributaries to tributaries to tributaries to tributaries of downstream jurisdictional waters are themselves jurisdictional, even if the flow of the tributary feature being evaluated is ephemeral or rare.

The agencies have taken a similar approach with respect to "adjacent" waters. Under existing regulations, wetlands "bordering, contiguous [to], or neighboring" jurisdictional waters are designated jurisdictional. The new rule, however, adopts an approach that asserts jurisdiction over features well beyond those that are next to, or in physical contact with, otherwise jurisdictional waters. A water feature is "adjacent," and therefore jurisdictional per se, if it is: (i) within 100 feet of the ordinary high water mark of an otherwise jurisdictional water, including a jurisdictional "tributary"; (ii) within the 100-year floodplain of any jurisdictional water, including a jurisdictional "tributary," and within 1,500 feet of that jurisdictional water; or (iii) within 1,500 feet of the high tide line of any traditional navigable water, interstate water, or the territorial seas. It is essential to remember that, under the new rule, simply meeting these location-based criteria is sufficient basis for the agencies to assert jurisdiction over a water feature – no analysis of the hydrologic connectivity between the water being evaluated and the traditionally jurisdictional water is required.

Nor is this the end of the story. The expansion of per se jurisdictional categories does not relieve operators of the burden of conducting case-by-case scientific analyses to determine whether there is a "significant nexus" between a water feature and any traditionally jurisdictional water under many other circumstances. Under the new rule, such analyses are not only advised, they are required whenever a site: (i) contains prairie potholes, Carolina and Delmarva bays, pocosins, western vernal pools, and/or coastal prairie wetlands; (ii) is located within the 100-year floodplain of any traditional navigable water, interstate water, or the territorial seas (irrespective how wide the floodplain may be); or (iii) is within 4,000 feet of an otherwise jurisdictional water, including a jurisdictional "tributary." When a scientific analysis applied under these circumstances demonstrates hydrological, chemical, or biological connectivity between the site being evaluated and any downstream jurisdictional water, the site will be designated jurisdictional for purposes of the Clean Water Act, regardless where the site being evaluated is located.

Footnotes

1 33 U.S.C. § 1362(12).

2 33 U.S.C. § 1362(7).

3 547 U.S. 715 (2006).

4 80 Fed. Reg. 37,054, 37,055 (June 29, 2015).

5 80 Fed. Reg. at 37,055.

6 Id. at 37,074.

7 Id.

8 Id. at 37.055.

9 Id. at 37,060.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.