Introduction

The purpose of this article is to analyse and summarise the emergence of the public-private partnership (PPP) model in the Middle East context (with a focus on the Gulf Cooperation Council (consisting of Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates) (GCC)) and also in the context of selected emerging markets in Africa that have recently looked to introduce the PPP model. Although Governments and the private sector have a history of working together to procure energy, infrastructure and other projects in these regions, they have largely done so in the absence of codified or other clear PPP legal frameworks of the kind seen in more developed jurisdictions.

With oil prices continuing to stall and without any obvious signs of recovery, and with fiscal deficits beginning to be seen across the region, Governments in the GCC are looking to step away from their traditional reliance on oil revenues and sovereign reserves in order to continue with their ambitious plans for development. Populations continue to grow and require more sophisticated infrastructure and services, and increasing industrialisation and the recognition of the need for economic diversification all mean that the GCC nations are, like many others, looking to new methods of financing projects. Likewise in Africa, population growth remains staggeringly high and a continuation of budgetary limitations for Governments also means that alterative methods for funding infrastructure and services needs must be found. It is becoming apparent that PPPs lie at the forefront of such alternative methods.

In order to implement this change in direction, certain of the jurisdictions in the GCC and Africa already have, and other jurisdictions are in the process of developing, viable PPP legal frameworks. The rationale for this is not only to provide legal certainty for foreign investors who may be hesitant to invest heavily in markets with under-developed legal systems, but to set out clear boundaries in relation to matters which are important to all project parties, such as risk allocation and mitigation.

This article provides a brief introductory overview of the PPP model generally, its history in the GCC and selected jurisdictions in Africa, challenges which are inherent in its successful implementation and a summary of the implementation of PPP legal frameworks within the GCC and selected jurisdictions in Africa. What will become clear is that although each jurisdiction is at a different stage of developing its own PPP legal framework, there is a distinct political will and necessity to embrace the PPP model which has been largely successful in the wider international projects market.

Reference in this article to "projects" or "PPP projects" (which terms are used interchangeably) are not intended, unless otherwise specified, to be a reference to projects in any particular sector. The broad principles explored in this article can, by and large, be applied to infrastructure, transportation, energy, education, healthcare and other sectors. Likewise, references to "Governments" are intended to mean the relevant Government and/or the relevant procuring Government entities.

What is PPP?

The term "public-private partnership" does not have a particular legal meaning per se. It can be used to describe a wide variety of arrangements involving the public and private sectors working together in some way. It is therefore necessary to be very clear about why the public sector is looking to partner with the private sector, what forms of PPP they have in mind, and how they should articulate this complex concept.

Among the key rationale for the use of the PPP model in the context of projects are the following:

- the utilisation of private sector capital and expertise for the efficient procurement of Government projects;

- more certainty for project delivery timelines and budgets;

- the sharing and allocation of risk as between the Government and the private sector parties, to that party best placed to manage such risks; and

- the easing of Governments' balance sheets and the freeing of capital to be directed towards other needs.

As the name suggests, PPPs are considered a partnership (in the broadest sense) between Governments and the private sector, not a divestment of responsibility. While the Government retains overall responsibility for delivering the particular service, the means and responsibility for such delivery are passed to the private sector. The Government retains control over the means of delivery by way of intricate and detailed payment and performance mechanisms.

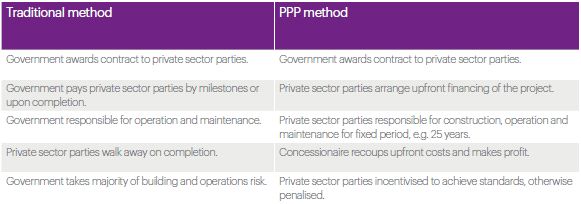

The following table compares certain key elements of projects procured using traditional methods, to those procured using the PPP model:

There is no single or 'standard' form of PPP project or structure.

A PPP project can essentially take whatever form the parties desire in order to meet the objectives of the project in question. However, a few of the more common forms implemented include the following:

- Build-operate-and-transfer (BOT) – the private party usually undertakes the designing, building and financing of the relevant facility. Once completed, the private party then carries out the operation and maintenance of the facility during which times it is allowed to charge facility users appropriate tolls, fees, rentals and charges not exceeding those proposed in its bid or as negotiated and incorporated in the relevant contracts with the Government. The facility is transferred to the Government at the end of the fixed term; these are sometimes referred to as "DBFO(T)" projects.

- Build-own-and-operate (BOO) – this is similar to the BOT arrangement, although the private parties retain ownership of the facility at the end of the fixed term.

- Build-transfer-and-operate (BTO) – this is another variation of the BTO arrangement whereby title to the facility is transferred to the Government, whilst the private parties retain the right to operate and maintain the facility on behalf of the Government.

- Rehabilitate-operate-transfer (ROT) – this is similar to the BTO arrangement; however, it involves the rehabilitation or upgrade of an existing facility rather than construction of a new facility. Following rehabilitation or upgrade, the concessionaire operates the facility in the same way as a BOT and then transfers it back to Government at the end of the agreed period.

- Lease – this is a model whereby a Government entity leases a public facility or land to a private party. The private party is usually only required to operate a facility or develop land. The private party is required to pay the Government leasing fees and its own revenue stream is user-pay charges.

Structure of PPPs

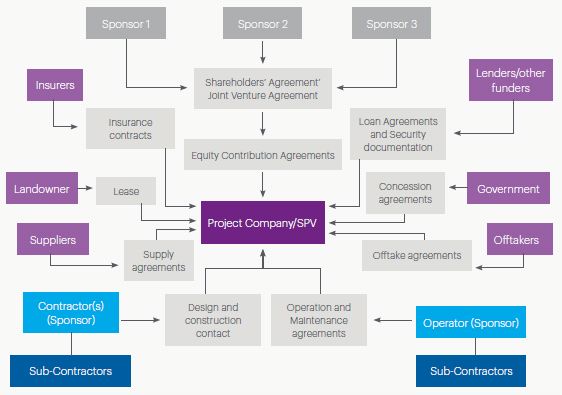

The diagram below sets out the key parties and contracts in a typical PPP project. Note that not all of these parties and contracts will necessarily appear in all PPP projects, depending on the parties involved, project sector, jurisdiction etc. – this diagram is by way of illustration only of what is common/typical.

An in-depth discussion on the role of each party in a PPP project is beyond the remit of this article. However, in order to better understand the purpose and objectives of PPP projects, it is helpful to understand the broad role of the major parties and documents in a typical PPP project. These are:

Government

The Government, as the procurer of the project, is obviously a very central figure in any PPP arrangement. The contract which underpins the relationship between Government and the private parties (which usually act through a special purpose vehicle or special purpose company (SPV) incorporated by the sponsor(s)) is usually a Concession Agreement and/or an Offtake Agreement. A Concession Agreement would be used, for example, in a road project, and sets out the rights, responsibilities and risk allocation for each party and will also set out the basis upon which the SPV will generate its revenues (usually either through availability payments from the Government or the right to charge tolls for use of the road). An Offtake Agreement would be used, for example, for an energy project, and is a long-term agreement whereby the Government entity agrees to make payments to the SPV over the life of the contract for the relevant output such as water or electricity (usually through capacity and output payments).

As the Government has a strong interest in delivery of the project, on time and to the requisite standard, it is common for it to have step-in rights under the relevant agreement(s) in the event the project is not implemented correctly. These stepin rights supplement various other performance controls and penalties agreed between the parties.

Generally speaking, it will also be the Government which is responsible for procuring the project site which would be leased or licensed to the SPV for the period of construction and operation.

Private parties/sponsors

The sponsor(s), acting through an SPV, is the Government's main, and usually only, counterparty to the Concession Agreement and/ or Offtake Agreement (although the lenders will usually have an indirect interest through a direct agreement). The SPV bears responsibility for the design, financing, construction, operation and maintenance of the project, although, apart from financing, many of such responsibilities are commonly passed down to contractors and operators (who are often the sponsor(s) themselves or their affiliates) and/ or their subcontractors. The SPV is remunerated as set out above.

Lenders

The lenders to the SPV play a critical role in any PPP project. The ability for the lenders to be repaid lies almost exclusively with the success or failure of the project. It is for this reason that the lenders are intimately involved with all aspects of project negotiations and risk allocation. For example, the lenders would need to be comfortable that the Concession Agreement and/or Offtake Agreement is in sufficient form, as it is the SPV's revenue pursuant to such documents which will dictate the ability of the SPV to repay its loan facilities with the lenders.

Part of lenders' recourse usually includes step-in rights in the event the SPV is unable to carry out the project as envisaged. Lenders will also take security over all of the assets of the SPV/project.

To continue reading this article, please click here.

About Dentons

Dentons is the world's first polycentric global law firm. A top 20 firm on the Acritas 2015 Global Elite Brand Index, the Firm is committed to challenging the status quo in delivering consistent and uncompromising quality and value in new and inventive ways. Driven to provide clients a competitive edge, and connected to the communities where its clients want to do business, Dentons knows that understanding local cultures is crucial to successfully completing a deal, resolving a dispute or solving a business challenge. Now the world's largest law firm, Dentons' global team builds agile, tailored solutions to meet the local, national and global needs of private and public clients of any size in more than 125 locations serving 50-plus countries. www.dentons.com.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.