On April 4, 2016, the IRS and U.S. Treasury Department issued proposed Treasury Regulations designed to curb the ability of large multinational companies to reduce their U.S. taxable income by engaging in "earnings stripping" practices (the "Proposed Regulations").1 If finalized, these rules, promulgated under section 385 of the Internal Revenue Code, would significantly impede several tax-planning options available to large multinationals.

Notwithstanding the ominous implications, the Proposed Regulations are subject to three major limitations. First, they apply only to related-party debt—specifically, so-called "expanded group instruments," or "EGIs."2. Second, they will impact only large corporations.3 Third, as Proposed Regulations, the new rules do not yet have the force of law and generally will go into effect no earlier than the date on which ultimately finalized.4

One of the key features of the Proposed Regulations is the requirement that affected taxpayers contemporaneously document related-party debt. Under this rule, taxpayers would generally be required to document both the commercial terms of the lending and an analysis of the creditworthiness of the debtor within 30 days of the lending, as well as satisfy certain ongoing maintenance requirements. Another key feature includes rules that recharacterize debt instruments issued in certain related-party transactions as equity. The Proposed Regulations also provide that the IRS on exam (but not the taxpayers) may bifurcate a single financial instrument issued between related parties between a combination of debt and equity. This portion of the rules will therefore affect common financial transactions, including for instance, cash pooling and treasury management activities.

The Proposed Regulations cast an extremely wide net and, if finalized, would easily be among the most ambitious and aggressive tax provisions promulgated by the Treasury in recent memory. Given the high stakes, while many practitioners doubt the Proposed Regulations will survive the review and comment process, there can be no doubt that if the Proposed Regulations fail, they will not fail due to any lack of initiative or creativity on the part of Treasury.5

I. Earnings Stripping – Background

As mentioned, the goal of the Proposed Regulations is to prevent multinationals from saving U.S. tax by way of earnings stripping.

A. What is "earnings stripping?"

"Earnings stripping" is the process of reducing (or "stripping") the taxable income of a U.S. taxpayer through deductible payments. In a typical earnings stripping structure, a foreign entity in a low tax jurisdiction lends to an affiliated U.S. corporation, allowing for the U.S. debtor corporation to reduce its taxable income by paying deductible interest expense to its foreign creditor. Although the foreign creditor will presumably recognize taxable interest income in the foreign country, to the extent that the U.S. tax rate exceeds the foreign tax rate, the U.S. deduction will result in tax savings for the group as a whole.

Current rules under Section 163(j) of the Internal Revenue Code provide a limitation on this practice. When interest expense is paid from a U.S. person to a person who is not a U.S. taxpayer6 and the debt-to-equity ratio of the U.S. debtor exceeds 1.5 to 1, the amount of the U.S. debtor's deductible interest expense will be limited to 50% of the debtor's adjusted taxable income.7 However, because this limitation is based on income,8 if the U.S. debtor is an operating entity generating substantial earnings, a significant amount of interest expense may remain deductible and therefore allow for significant earnings stripping, notwithstanding the section 163(j) limitation.

B. Section 385

In addition to section 163(j), section 385 is a potential weapon at Treasury's disposal to combat earnings stripping. This is the mechanism adopted by the Proposed Regulations. Section 385 allows Treasury to prescribe such regulations as may be necessary or appropriate to determine whether an interest in a corporation is to be treated as stock or indebtedness (or as stock in part and indebtedness in part). Under such a rule, the Proposed Regulations would thereby be able to disregard the label explicitly assigned to a debt instrument by a taxpayer and treat the instrument instead as equity in whole or in part. There are currently no regulations in effect on earnings stripping under section 385,9 so debt versus equity determinations heretofore have been largely the product of case law and other informal IRS guidance.

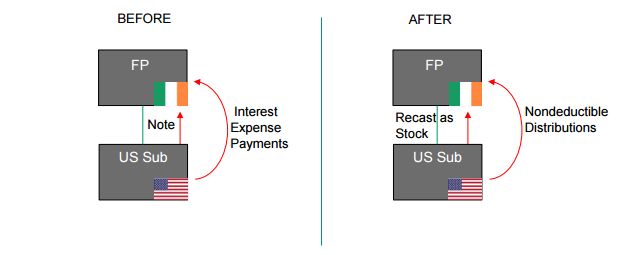

The potential effect of characterizing debt as equity under the Proposed Regulations is illustrated below. For purposes of the example, assume that FP is an Irish corporation taxed at 12.5% on all corporate income and that U.S. Sub is its wholly-owned subsidiary corporation, which is subject to corporate tax of 35% on all income. In the example, U.S. Sub distributes a Note to FP as a dividend:

Prior to the Proposed Regulations, U.S. Sub would be able to deduct interest expense payments on the Note issued to FP, while FP takes into account interest income, which is taxed at the Irish corporate tax rate of 12.5%. The income that is effectively "shifted" by U.S. Sub to FP results in a savings of 22.5% (i.e., the 35% U.S. corporate rate minus the 12.5% Irish rate) to the FP-U.S. Sub group. Contrast this with the result after finalization of the Proposed Regulations, as depicted on the right side of the diagram. With the Note recast as equity, the payments from U.S. Sub to FP are recast as dividend distributions and are therefore not deductible to U.S. Sub. Accordingly, no earnings stripping or erosion of the U.S. tax base is possible, and all corresponding tax savings are denied to the expanded group.10

II. The Proposed Regulations (Prop. Reg. § 1.385-1 through Prop. Reg. § 1.385-4)

The Proposed Regulations are organized into four sections which provide (1) general provisions (including, for example, rules that under certain circumstances recharacterize only a portion of a debt instrument as equity),11 (2) contemporaneous documentation requirements,12 (3) special consolidated group rules,13 and, most importantly, rules which implement the recharacterization of debt as equity in the situations described in the following paragraph.14 The Proposed Regulations are effective for debt instruments issued on or after the date the Proposed Regulations are finalized, although the recharacterization rules described below are proposed to apply to debt instruments issued on or after April 4, 2016 (with such instruments continuing to be treated as indebtedness during an additional 90-day grace period after finalization).15

Because the United States has one of the highest corporate tax rates in the world,16 there is an almost ever-present incentive in a multinational structure to saddle U.S. member entities with as much debt as possible, regardless of what other jurisdictions are involved. Given capital constraints, it is therefore common for a U.S. company (as depicted in the illustration above) to simply distribute a note to a foreign related party in order to jumpstart the earnings stripping process, even when the only purpose of such indebtedness is to create tax savings. The Proposed Regulations evidence Treasury's belief that this practice is abusive,17 and would use the authority granted by section 385 to recast purported indebtedness as equity in the following specific cases when:

- Debt is "pushed down" into U.S. subsidiaries by causing U.S. subsidiaries to directly distribute a note to new foreign parent as a distribution with respect to their stock (e.g., a dividend);

- Debt is pushed down into U.S. subsidiaries through a two-step process whereby a U.S. subsidiary borrows cash from a related company and then makes a distribution with respect to its stock (e.g., a dividend) to its foreign parent; and

- A U.S. purchaser acquires stock of a related foreign company using debt, creating the same effect as if it had distributed a note as a dividend distribution.

To summarize, where large taxpayers have issued related-party debt, the Proposed Regulations provide three hurdles the debt must "clear" in order to survive recharacterization as equity: (1) the new documentation requirements, (2) the new transactional requirements recasting debt as equity, and (3) traditional debt versus equity principles. As can be seen, the old test involved one hurdle, while the new test has three. Accordingly, a failure to satisfy any one of the three separate tests will result in the issued debt being recast as equity.18 As elaborated below, a host of consequences, some anticipated and many perhaps not, are sure to follow.

To continue reading this article, please click here

Footnotes

1 81 Fed. Reg. 20912 (proposed Apr. 8, 2016). The Proposed Regulations were issued at the same time as Temporary Regulations, T.D. 9761, 81 Fed. Reg. 20857 (April 4, 2016), which in large part target so-called "inversion" transactions. These Temporary Regulations have already gained notoriety by single-handedly thwarting the $160 billion Pfizer-Allergan merger. The Proposed Regulations, on the other hand, cover an even wider scope, targeting earnings stripping practices both within and without the context of inversion transactions.

2 Under Prop Reg. § 1.385-2(a)(4)(ii), an expanded group instrument, or EGI, is an applicable instrument the issuer of which is one member of an expanded group and the holder of which is another member of the same expanded group. For these purposes, an "expanded group" is a chain of related corporations within the meaning of section 1504(a), without regard to the various restrictions under section 1504(b)(1) through 1504(b)(8), such as, importantly, the rule in section 1504(b)(3) that would otherwise exclude a foreign corporation from the group.

3 There are effectively two thresholds involved: one which applies to the documentation requirements of the Proposed Regulations and one which applies to the debt instruments themselves, both of which substantially restrict the ambit and effect of the Proposed Regulations. The documentation requirements apply to expanded groups (defined below) if either (1) the stock of a member of the expanded group is publicly traded or (2) financial statements of the expanded group or its members show total assets exceeding $100 million or annual total revenue exceeding $50 million. The other debt recharacterization rules apply to the extent that, when issued, the aggregate issue price of all expanded group debt instruments that would otherwise be treated as stock under the new rules exceeds $50 million. Prop. Reg. § 1.385-2(a)(2); Prop. Reg. § 1.385-3(c)(2).

4 Prop. Reg. § 1.385-3(h)(1) provides a transitional rule which will render only debt instruments that are issued on or after April 4, 2016 subject to potential recharacterization as equity.

5 The Treasury Department website indicates that it intends to act quickly to finalize the Proposed Regulations. https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/jl0404.aspx.

6 This could be either a foreign person or a U.S. tax-exempt entity.

7 Effectively, the concept of adjusted taxable income under section 163(j) approximates the accounting/financial concept of earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA).

8 This limitation is in contrast to the anti-earnings stripping provisions of many foreign jurisdictions, which focus entirely on a maximum permissible debt-to-equity ratio.

9 On March 24, 1980, Treasury and the IRS published a notice of proposed rulemaking in the Federal Register (45 FR 18959) under section 385 relating to the treatment of certain interests in corporations as stock or indebtedness. LR-1661, 45 Fed. Reg. 18959 (proposed March 24, 1980). Final regulations were published in the Federal Register on December 31, 1980, which were subsequently revised three times in 1981 and 1982. T.D. 7747, 45 Fed. Reg. 86438 (December 31, 1980). Finally, the Treasury Department and the IRS completely withdrew the section 385 regulations. T.D. 7920 Fed. Reg. 48 Fed. Reg. 50711 (July 6, 1983).

10 In this sense, an anti-earnings stripping provision under Section 385 would seem to impose a more failproof combatant of earnings stripping than, for example, simply increasing or otherwise strengthening the limitation under section 163(j). The section 385 approach will also bring about withholding tax consequences, under which (1) dividends may be taxed at a different rate than interest expense under an applicable treaty and (2) a greater portion of payments may be subject to US tax by virtue of the inability to characterize a portion of payments as repayments of principal.

11 These provisions, included in Prop. Reg. § 1.385-1, include both definitions and specific mechanics involved in recharacterizing debt as equity for tax purposes.

12 Prop. Reg. § 1.385-2

13 Prop. Reg. § 1.385-1(e); Prop. Reg. § 1.385-4.

14 Prop. Reg. § 1.385-3.

15 Prop. Reg. § 1.385-3(h)(3) provides that when recharacterization would otherwise take effect prior to the date the Proposed Regulations are finalized, the debt instrument will be treated as indebtedness until the date that is 90 days after the date the Proposed Regulations are finalized. The transitional rule, which imposes the April 4 bright-line issuance date, is included in Prop. Reg. § 1.385-3(h)(1) and Prop. Reg. § 1.385-3(h)(2).

16 As of 2015, the United States has, along with Puerto Rico, the third highest corporate tax rate in the world, exceeded only by the United Arab Emirates and Chad, neither of which are in the OECD's group of 34 industrialized nations. At an effective rate (factoring in state and local tax) of approximately 39%, the U.S. rate is also 16 percentage points higher than the worldwide average of 22.8%. OECD Tax Database, Table II.1 – Corporate income tax rates: basic/non-targeted, May 2015, http://www.oecd.org/tax/tax-policy/tax-database.htm.

17 The Proposed Regulations recognize that introducing debt into a structure for business purposes is not indicative of this abuse, and there is therefore an exception for infusion of debt in the ordinary course of business.

18 To the extent debt is recharacterized as equity, there is a deemed exchange whereby the holder is treated as having realized an amount equal to the holder's adjusted basis in that portion of the debt as of the date of the deemed exchange (and as having basis in the stock deemed to be received equal to that amount), and the issuer is treated as having retired that portion of the debt for an amount equal to its adjusted issue price as of the date of the deemed exchange. Prop. Reg. § 1.385-1(c). The mechanics of this deemed exchange are similar to those described under section 108(e)(6) in the context of a related-party debt instrument evidencing debt owed by a subsidiary to its parent and which is retired by way of a contribution to capital. When applicable, no income would be recognized (including cancellation of indebtedness) on the deemed exchange, except any foreign currency gain under section 988.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.